Atmospheres of the Undead: living with viruses, loneliness, and neoliberalism

Caitlin Berrigan

September 2020

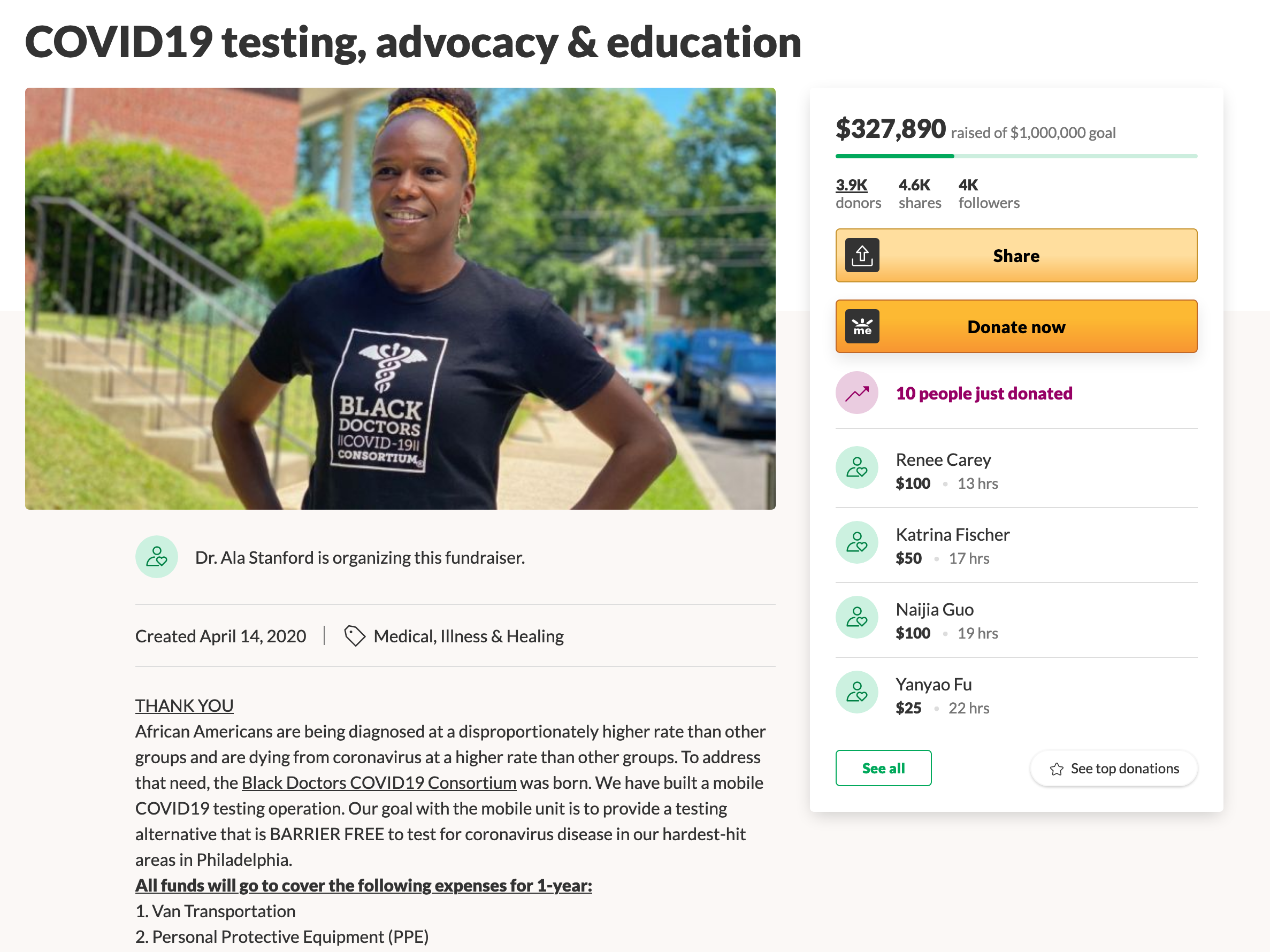

The comments posted on gofundme.com’s medical fundraisers form an archive of mutual aid in response to a ruthless for-profit health system. It is an archive that should not exist.

AUDIO VERSION by Caitlin Berrigan.

“I’m sick of being Mr. Good Patient. Gimme drugs.”

– Bob Flanagan, The Pain Journal1

A virus is an undead vector that traces both the beauty and abuses of our mutual reliance. The porosity of our bodies is the very interface of our social being. Where we connect and communicate lies risk for contagion. Porosity affirms that we are already multiple, interdependent and entangled. A virus is not a metaphor.2 Different viruses trace divergent choreographies of vulnerability, sociality, and capital markets. Their movements within our social and material lives can draw our attention to critical nodes.3

One of these nodes is where notions of care and cure intersect, yet they must not be conflated. A biomedical cure for a virus depends upon—but is not the same as—the infrastructures of care-taking required to support complex needs for public health such as food, shelter, bodily autonomy, and mental health. Another critical node is where mystification and lack of open participation in decisions about pricing policies for publicly funded biomedical innovation enables the enduring power of pharmaceutical companies to prioritize profit over people’s lives in the face of public health crises.

How can I narrate to you the decades I negotiated life with one virus and situate all I learned within this emergent moment of the novel coronavirus? I feel like Cassandra, flailing Plebeian waif at the sidelines with a flood in her mouth, witnessing and warning of the toxic mix of racial capitalism and fear that will normalize and marginalize life with COVID-19 as soon as the privileged bodies are either cloistered or vaccinated, and the mood of solidarity subsides. Viruses are instrumentalized as vectors of ideology and biopower.4 The attentions I cultivated towards choreographies of risk and responsibility are again relevant to the present moment, as well as the contours I traced around the black boxed edges of the financialized global health sector. I will intertwine these viral narratives for you here, as they direct our attentions to the invisible gaps between us where we know material interactions are occurring, but we have poorly developed senses to perceive them.

Living together with a virus is a lonely way of being.

Living together with a virus is a lonely way of being. As my peers individuated from dependent adolescents into adulthood, my coming of age was not as a singular human subject. I was already multiple: a human carrying an alien viral load. My subjectivity was shaped by an awareness of having been seeded and colonized by an undead thing: an endless genetic proliferation with no known purpose other than to repeat itself in me and possibly to use me as a vector of infection. From the time of my medical diagnosis at the age of seventeen, this multiplied subjectivity paradoxically rendered me ever more singular, as the contagious effects of social stigma isolated me from other human beings. First, as an abject body to be feared; second, as a suspected user of intravenous drugs; and third, as an outlier: both an anomaly within the typical demographics of the diseased, and a chronically ill outlier among my carefree friends.

As we followed the North American middle-class rites of passage from high school into college, I was excluded from my peers’ deliverance of their bodies to each other during substance-altered states of sex and social bonding. The ecstatic self-destruction of these rituals would, I was warned, most certainly destroy my already overburdened liver within a few short years and necessitate a liver transplant. Given the unquenchable demand for livers, the logic of medical rationing was such that I would be placed at the bottom of the national organ waitlist since I would reinfect it with the virus anyway and damage a good liver upon receipt. Instead, I delivered my young body to the vast medical apparatuses of international health insurances, clinical trials, alternative therapies, and theories of harm reduction and self-care.

I had no one with whom to share my experience of this particular virus with a bland and confusing name. It emerged slowly upon the scene of public health in the 1970’s, categorized as a liver disease called “non-A-non-B” viral hepatitis. When properly identified in 1989, the virus gained its own letter: hepatitis C (HCV).5 The name perpetuates confusion in efforts to inform the public because it shares no relation to hepatitis A or B. There was no bestial, racialized or xenophobic outbreak narrative6 that could situate a foreign origin and infiltration of the human body in space and time, as those that accompanied viruses such as HIV, H1N1 Swine Flu, H5N1 Avian Influenza, and SARS-CoV-2 (the human coronavirus that causes COVID-19).7 With a slow but deadly disease progression, the hepatitis C virus has made itself hyperendemic within the human population without ever making a lasting impression on the social imaginary. HCV affects over 71 million people, second to hepatitis B as the most widespread chronic viral illness worldwide, and kills a loose half million each year.8 Despite an ongoing global health crisis of proportionately immense scale, there is little public awareness and scant patient advocacy. HCV affects disparate demographics of already socially marginalized people with intravenous drug dependency, the poor, people in need of mental healthcare, first responders, war veterans, and prisoners. Without the existing bonds of community, no cohesive “biosociality” emerged—a term conceived by Paul Rabinow to describe a biomedically-driven bond within stronger axes of shared identification that propels effective advocacy.9

It was hard for me to understand feeling isolated despite millions of people out there like me. Over time, I became aware that my loneliness was symptomatic of the permeations of neoliberal ideology10 within the broad and contested concepts of health and care.11 One ethical ideological notion of public health is as a common good that benefits everyone. When people are able to access the care they desire, they have greater capacity to actively participate in their lives and connect with others. The ability of the body to labor is of critical concern to politics. Taking measures to treat people with destructive contagious diseases prevents them from spreading. The multiplicity of interdependent bodies within this notion of public health contradicts how neoliberal ideology has shaped it into a transactional relationship between an individual consumer and a commodified health system that, for those in a position of access, extracts profit in exchange for life. As Angela Davis says, “neoliberal logic assumes that the fundamental unit of society is the (abstract) individual,”12 while simultaneously enacting en masse what Ruth Wilson Gilmore has called the “organized abandonment” of vulnerable communities from social structures.13 In other words, neoliberal biopolitics amplify and multiply the loneliness of wellness. Gradients of vulnerability to the effects of disease fade into the horizon of neoliberal subjectivation, as they become individual responsibilities rather than mutual concerns of the common good.

A sharpened awareness of leaking accompanied the formation of my sense of self. The hepatitis C virus courses through the blood, but is not found in other bodily fluids. I followed the material movements of blood with fascination. Each time my skin opened and released a vital stain of iron, protein and virus, I covered the wound with hypervigilance and let no bloody flake of a booger escape biosafe disposal. I developed a sensory attention to where I deposited and picked up residues at all times, as one develops a subconscious awareness for the felt presence of the pet under the couch gone quiet, for where the baby has wandered. I adapted to view the world as a sea of particulate interactions.14

Multiple again, I am a particulate cloud, an assemblage, an unknown quantity as I move through the streets.

Cultivating attentive responsibility towards overwhelming biotic details has returned with coronavirus and it has proliferated.15 We are not just leaky vessels that drop fluids onto surfaces. We have become atmospheres. The clouds of others press upon us in awkward choreographies. I strap on a mask in an effort to contain my breath, but the gentle gas escapes through the relaxed edge of fabric on my humidified cheeks. Multiple again, I am a particulate cloud, an assemblage, an unknown quantity as I move through the streets.16

I contracted the hepatitis C virus as a four-month-old baby from a blood transfusion during surgery. It was 1981, the year HIV was identified. Ronald Reagan was president of the United States and hospitals paid the poor for their blood. The donations were fractioned and combined with the cells of thousands of other donors and turned into commercial pharmaceutical products. Concentrated human-derived plasma and clotting factors for hemophiliacs were especially lucrative.17 Despite the discovery of HIV and the subsequent deaths of thousands of people with hemophilia, the devastatingly infectious clotting factor was not immediately pulled from the U.S. market. My great uncle was a clinician-researcher among those who had developed an effective clotting medication that has been continually in use since its FDA-approval in 1964, and claims their alternative was ignored because it was cheap.18 Bayer continued to sell millions of dollars worth of its contaminated blood product reserves in Asia, Latin America, Canada and some European countries for a few more years until 1985.19 By this time, 50 percent of hemophiliacs had been infected with HIV and at least 90 percent with hepatitis C.20

After my diagnosis in high school, I looked for books about HCV and found only one with the frank title: The Silent Killer.21 Death itself did not frighten me, but the invisibly slow disease progression struck me as painful, abject, and lacking glamor. Since 1992, blood is screened for HCV, making contaminated drug needles the primary route of its transmission in the U.S.22 The association with drug use marks it with powerful stigma. In some countries of high prevalence such as Egypt and Pakistan, contaminated medical equipment drove transmission. Sexual transmission is rare.23

Inspired by HIV/AIDS communities and disability activism, I was open and unashamed about having hepatitis C, but I strategically withheld the origin story of its transmission unless someone inquired. It was my way to be a Bartleby: “I prefer not to” participate in the cycle of stigma by voluntarily excusing myself from being held individually responsible for “lifestyle choices.” Silence allowed me to monitor the mutating shapes of biopolitical discipline across speech and behaviors as people vocalized to me sundry assumptions and offenses. Alongside the health consequences of the virus, the social contagion of stigma was a life-changing force that required constant negotiation throughout my personal, professional, and medical encounters.

Framing drug use as a lifestyle choice fuels its moralization and the obstruction of safe injection programs at a time when new infections of HCV and HIV have been accelerating among the survivors of opioid and heroin dependence. This appetite for opioids in the past several years was, as we now know, deliberately cultivated by major pharmaceutical companies in the U.S. to create a market for their prescription painkillers.24 It is not a lifestyle choice, but rather organized abandonment when addiction and HCV burden especially the poor, people in need of mental healthcare, veterans and prisoners. The proximate and unhygienic conditions of incarceration make it a site of risk for contracting HCV, as it is for the coronavirus. Although the majority of people in the U.S. with HCV are white (as am I), prevalence is highest among Indigenous North Americans, and three to five times higher among Black and Latinx men.25 This incidence does not correlate to higher rates of drug use, but rather to the racial injustices of mass incarceration and the criminalization of poverty that make prison itself a vector of infection.26 The absence of a universal legal right to healthcare in the U.S. makes it challenging for the incarcerated to gain treatment.27 It took more than two years and a federal lawsuit before a judge granted treatment for hepatitis C to the renowned political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal, and only then because his condition had significantly worsened.28 What happens in prison is merely the most concentrated form of how racism and organized abandonment are responsible for disproportionate disease burden and barriers to treatment for people of color. The logics of eugenics are at work in the effects of structural racism on health, and as the obvious and alarming explanation for the increased vulnerability of people of color to the ravages of COVID-19.29 Yet as medical professionals have said: “The response to the (coronavirus) pandemic has made at least one thing clear: systemic change can in fact happen overnight.”30

Half a million deaths each year from hepatitis C are utterly normalized because they are mostly the deaths of people with a low income and people who live in the Global South. The death toll is only an estimation, as coroners are not systematically required to track HCV, and many deaths are attributed to the virus’s secondary effects of liver disease or cancer. The excess mortalities of millions of people with preventable and treatable diseases are now the normalized measure against which data scientists estimate death counts from COVID-19 while infrastructure for testing and data tracking is lacking and suppressed.31

Living co-inhabited with a virus for 34 years has taught me that survivance is negotiation, not warfare.

Death is not our only concern, however. Living co-inhabited with a virus for 34 years has taught me that survivance is negotiation, not warfare. There is no invisible enemy and militarized battle rhetoric is meaningless against a virus. Vulnerability is the condition of being in a body and eliminating the risks of contagion are impossible. We must cultivate the language to favor some things and reject others, without abstraction or xenophobia.32 The success of health interventions is always dependent upon basic needs being met with stable shelter, food, hygiene, essential health services, and clean water. It is behind the popular refusal to return to “normal” after COVID-19, in which health and access to medicine is structured within a racialized global caste system. With the majority of the global population living with chronic conditions, illness is not temporary.33 The durational struggle lies in fostering collective mutualities of care, both interpersonally within our communities and formally across the health infrastructures of international and state institutions, including shared power structures for biomedical cures. Conventional pharmacological medicine cannot care for all health conditions, but when it can, we want it. It is ours. No matter how robust our networks of care, survivance of viruses puts us in negotiation with the Faustian pharmaceutical industry.

At the time of my diagnosis in 1998, there was only one medication: year-long, weekly high-dose injections of synthetic interferon34 that could cure HCV in a minority of patients, but caused debilitating side effects, and left some with permanent disabilities. A slightly improved version was on track for FDA approval, but it would not be available until after I graduated college, when I faced the possibility of being uninsured.35 My only chance to be cured of HCV was to enroll in a Phase 3 clinical trial without placebos while I was still young enough for coverage under my dad’s insurance to pay for it. Aged 19, I took medical leave from college, found a job to support myself, scoured clinical trial advertisements, interviewed with research physicians across the country, and was accepted into a Phase 3 trial that, luckily for me, was located two and half hours away in Boston.36 A nurse demonstrated how to self-administer the medication by injecting the refrigerated fluid into a pinch of belly fat. Acute symptoms of systemic organ failure immediately followed my first dose. Within days I was removed from the trial. The reason for the near-fatal reaction was not investigated. The clinical language was that I had “failed” the treatment, and counted as a statistical outlier.

Too late to return to college, for the rest of my medical leave I worked full-time as a production assistant at the Media Education Foundation, producing a documentary about the public relations industry called, Toxic Sludge is Good For You. I developed a sensory attention to identify cues left by pharma branding in footage that no local news agency could possibly afford to produce, such as whizzing Fordian factory belts of candy-colored lozenge manufacture—close-up with shallow depth of field on the pill imprint code—or the intimate interview with a healthy white mom, viscous with gratitude for her child’s new lease on life as he rolls naughtily in the saturated turf behind her in a rural region underserved by both independent media and hospitals alike. I learned to recognize how news related to medicine is rarely written by journalists, but rather lifted directly from press releases and video reels featuring paid scientists and patient narratives that were produced and distributed by public relations firms on behalf of pharmaceutical clients. Nine out of ten of the biggest international pharmaceutical companies spend more money on sales and marketing than they do on the research and development of new treatments.37 The signals of promising innovations are lures for shareholders, and encourage patients to request the patented drugs from their physicians, to whom they also market directly.

Since I had “failed” treatment, learning to live with the virus was the only other option. Without romanticization or rancor, I accepted the viral alterity within and the likelihood that it would remain incurable. I avoided alcohol and drugs and became that person at the party who dances with too much enthusiasm. Daily symptoms included deep fatigue and a dull liver ache that could turn into a sudden stabbing and rob my speech. I slept long hours and still woke up groggy or missed the alarm, often tardy for morning classes and docked for laziness. However, I resisted externalized guilt for sleeping, knowing my body was working and repairing. My dream life was long and vivid. Having spent so much time there, it feels coextensive with my memories. Friends, teachers and colleagues could not discern visible evidence of my illness and helpfully suggested it was psychosomatic. It was the era of self-optimization and neoliberal gaslighting AKA the law of attraction, popularized by The Secret (2006), a self-help book that declares all dreams come true by shifting your thoughts towards a positive outlook. Breathe in: gently inhale the idea that you alone are the master of your own destiny. Breathe out: expel-exhale-dismiss systemic racism, economies of marginalization, and pre-existing conditions.

The only way to maintain health insurance after college was to find work in a full-time job with benefits. One day, gazing out the window of my shared office in New York, I was overtaken by severe kidney pain and nausea. The mysterious condition persisted and for a month I could not walk farther than a block before collapsing in exhaustion. Wearing clothes hurt my skin. Federal sick leave benefits offered $175 a month to replace my full-time salary, while I spent $850 in co-pays on the diagnosis: autoimmune complications from stress-induced hepatitis. Like a 19th century novel, the only treatment was extended bed rest.

My 24-year-old body could not sustain the labor of a full-time job. I lost health insurance, but was still denied coverage under federal disability. My only remaining option was to live in a handful of states that offered Medicaid (guaranteed federal health insurance)—as long as I remained poor enough to qualify. Caring for chronic illness is impoverishing and precarious work. The coronavirus pandemic recession has put millions of people in the U.S. in a similar situation, having lost their jobs and thus, the health coverage tied to it, with women with disabilities and Black and Latinx women facing the highest job losses.38 At the same time, private health insurers have seen profit gains in 2020 that are anticipated to grow in 2021, as individuals take to the marketplace and pay higher out-of-pocket premiums than those negotiated in volume by employers.39

Drug pricing is unregulated and requires no financial transparency.

Reducing the impact of infectious diseases on all bodies requires that people be tested and treated, giving urgency to the adoption of a mandate for universally accessible public health insurance.40 Although it would expand coverage for the millions of uninsured, a public option does not guarantee quality coverage,41 and would not automatically lead to a reduction in healthcare costs. Drug pricing is unregulated and requires no financial transparency. New legislation will be necessary to empower the government to negotiate the price of prescription drugs.42 Because the U.S. pays an average of 40 percent more for the list price of prescription drugs over other high-income nations, what happens with health insurance and drug pricing policy in the U.S. influences pricing strategies for the global market. This inflation does not, however, subsidize research and development, or access for low income countries, but instead results in overall increased profit margins for corporations.43 This consistent practice of monopolization through patents and pricing biomedicines for what the market can bear anticipates grave global disparities in access to vaccines and treatments for coronavirus.

Like the cumulative effects of liver inflammation, HCV profoundly shaped the direction of my life over time. Massachusetts became my home for a period of years because it was the only state in the nation with universal healthcare. I reoriented towards a profession with a flexible schedule because I could never have expectations of when my body would perform and when it would refuse. Completion upon an able-bodied agenda was a lightly held aspiration. Unquantifiable accretions of hours elided into cycling through medical facilities, being probed and measured, waiting, resting, accepting. What we are collectively experiencing now as pandemic time, those with chronic illness and disabilities know intimately as crip time: lagging, letting go.44

Except that crip time is durational over a lifetime. I grew older than the 20-30 years it can take to develop life-threatening cirrhosis. Compounding health conditions, such as HIV, can accelerate inflammation. Even with little scarring, risk of liver cancer increases over time. I witnessed several activist acquaintances die, despite having had HCV longer than they did. I decided it was a waste of energy to think about my death unless presented with evidence of its imminence. But at 25-years-old, I began exhibiting tumor markers indicating hepatocellular carcinoma, a deadly form of liver cancer that is survived only with a full liver transplant. Even then the survival odds are just 5-10 percent, and due to the aforementioned liver shortage, I would not be a candidate. Death became more proximate, and I was closely monitored for tumors thereafter.

Two hours each month for ten years, I methodically prepared daily doses of forty tablets each of Chinese medicinal herbs, distributing them into tiny plastic towers. My fingers maintain the tactile memory of smooth, clear gelatin coating pungent, tawny powders. The herbs and acupuncture treatments were effective at reversing liver scarring and reducing fatigue. They demonstrably prolonged and improved my quality of life, but they were not a cure for this virus. Insurance did not shoulder the expense, making wellness feel like a luxury. My working-class dad helped me pay for the $500 monthly bill, cumulatively $60,000.

My doctors kept me in the loop of hopeful studies for new treatments, always on the horizon. However, the scientists who were just awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Medicine45 for the identification of the hepatitis C virus patented its genome in 1993 upon identification (and numerous subsequent patents related to its genome and diagnostics), stifling research for two decades until the Supreme Court finally overturned an existing gene patent in 2013, ruling that naturally occurring genetic sequences are not novel enough innovations for patents.46 With research stalled due in part to the patent of the viral sequence, and meaningful non-prescription treatments an out-of-pocket expense, the care of a disease that affected so many millions of people was effectively abandoned to each individual’s capacity and income. Information pamphlets in doctors’ offices advised patients to avoid alcohol and drink lots of water, and encouraged us to join overwhelmingly white support groups in the lineage of Alcoholics Anonymous, a forum styled after Christianity to foster group identity around the locus of a shared wound.

Left alone to contend with the millions of viruses replicating in my bloodstream, I performed this loneliness in a work called Life Cycle of a Common Weed.47 I became certified in phlebotomy to draw my own infected blood and used it to fertilize dandelions which are an herbal treatment for liver and kidney disease. The dandelions enjoy rich nitrogen found in blood, and not being human, they remained unaffected by the virus. Dandelions are a maligned and weedy life form, just as I was an anxiety-provoking, loose container of viral multitudes. The exchange between us was unsustainable and absurdly inadequate: the herbal remedy was not enough to resolve my illness, while my need to uproot and devour the entire plant did not match the sprinkle of nitrogen I offered in return.

Gifts of any kind but especially of blood are highly ritualized and mediated across spheres of religion, the nation state, agriculture, and medicine. Humans are more likely to be responsive to intimate and identifiable people in need than to a generalization. A study of blood donation in Denmark offered insight into social choreographies that utilize human tendencies towards mutual reciprocity in order to maintain a stable flow of blood donations outside times of crisis.48 Denmark’s strategy involved nurses performing hospitality with offers of chocolate, orange juice, and gratitude for the gift of blood. In this interpersonal exchange, the medical personnel are surrogates for the abstract patient to be saved by the blood gift—despite its subsequent transformation into a commercial product with many possible uses.

The vaguely cannibalistic cycle of care in The Life Cycle of a Common Weed points to a tendency to sentimentalize the interpersonal intimacy of “mutual aid” as a micropolitical strategy of survivance when abandoned by organized infrastructures of medicine and social welfare. Self-reliance and mutual aid are often insufficient for the problem at hand, while they nonetheless call attention to essential needs and model how to care for them. Mutual aid can also be seen as a defiant expression of a lack of faith in normative political structures, and mutuality can be instrumentalized by strengthening those social bonds that concentrate political agency. It is an ideological praxis employed by movements with differing ethical frameworks, from the Black Panthers’ Free Medical Clinics and Free Breakfast for Children programs that pressured the government to prioritize Black health and child nutrition, to the controversial Dallas Buyer’s Club that circumvented federal regulations to speed up access to HIV medications, to faith-based groups that provide healthcare and material infrastructure in proximity to their forms of community and ideological messaging.49

Radical care and mutual aid are an empowering praxis of imagination and prefigurative politics. However, mutual aid should not substitute for robust social and healthcare infrastructures as our common goods.50 Many diagnostics and treatment innovations of technoscience that are capable of preventing mass death and suffering require production and dissemination that are not accomplished at this scale. At worst, disengagement from putting pressure on policies and practices of extraction and resorting to alternative care systems accomplishes the work of neoliberal ideologies of self-reliance.51 On precarious bodies, Judith Butler writes, “Reciprocally, (precariousness) implies being impinged upon by the exposure and dependency of others, most of whom remain anonymous. These are not necessarily relations of love or even of care, but constitute obligations toward others, most of whom we cannot name and do not know, and who may or may not bear traits of familiarity to an established sense of who ‘we’ are.”52 Assuming the radical alterity and proliferation of the virus is a strategy to resist both the isolation of neoliberalism and the limits of mutual aid driven by identification.

Assuming the radical alterity and proliferation of the virus is a strategy to resist both the isolation of neoliberalism and the limits of mutual aid driven by identification.

Neoliberalism obscures the fact that privatized innovations are extracted from our mutual efforts and resources. The intellectual property of the health care sector is the prize of capitalist technoscience and a prime example of this obfuscation. The common narrative of the pharmaceutical industry is that unregulated international markets compete for profits and drive innovation of life-saving treatments, while private investors take all financial risks. They warn that without the promise of high profits, no companies will be motivated to make new medicines and we will all suffer and die.53 Profit-oriented motivation currently neglects less profitable critical public health imperatives, such as antibiotic resistance and vaccine development. This narrative also ignores our collective contributions on multiple levels including maintaining a society stable enough to nurture and highly educate individuals for specialized careers in biomedicine. Immense, incremental knowledge production—academic, embodied, and narrative—provides the data and contextual understanding for pharmaceutical interventions to be effective within different environments and populations. We collectively provide our human and more-than-human bodies to experimental clinical trials.54 We collectively re-absorb through our permeable bodies the toxic byproducts of drug manufacture, primarily across landscapes and waterways in India, China, Kenya, and Puerto Rico, where environmental racism means that Black and brown people are disproportionately harmed.55

One third of pharmaceutical research and development in the U.S. is subsidized by taxpayers, who then pay an additional 40 percent markup on average for those drugs.

Let’s talk about money: we, the public, also contribute financially. Health spending in 2016 accounted for 8.6 percent of the global economy, of which 74 percent came from governments and 18.6 percent came from out-of-pocket spending.56 The majority of top pharma companies are headquartered in the U.S., with a handful of powerful companies based in Europe, China, and Japan. One out of every three dollars spent on drug research in the U.S. is publicly funded by taxpayers.57 Rest here on this important figure: One third of pharmaceutical research and development in the U.S. is subsidized by taxpayers, who then pay an additional 40 percent markup on average for those drugs. Meanwhile, the top 25 pharmaceutical companies enjoy an average net profit margin of 15-20 percent, versus most Fortune 500 companies that average 4-9 percent. Recall that drug companies spend more on marketing than on R&D. The narrative that the high price of prescription drugs is necessary to fund research is demonstrably false. Pharmaceuticals are among the most profitable companies on earth and we are dependent upon them for our lives. They are dependent upon us for their proportionately astronomical profits. Despite all of our public investments in the risky phase of innovation development, there are no regulations to ensure that benefits will come to global public health through equitable access and affordability.

Our mutual resources are siphoned into the commodified health sector, which allots the benefits through structural bias across race, class, gender and national citizenship. We are left isolated to contend with collective public health threats such as the coronavirus pandemic we are facing now. Nation states vie for exclusive contracts for vaccines and treatments. Individuals are responsible for personal protection equipment, clean water reserves, hygiene, viral testing, and socially distanced work and housing. Breaking mandated protocols can result in fines and criminalization. We are caught between the effects of loneliness imposed through neoliberal subjectivation—compounded by the aerosolized contagion of coronavirus that forces us to self-isolate and minimize contact with each other—and the subjectivation of multiplicity brought forward by viral replication and its indiscriminate proliferation across all human bodies.

Imagine if technoscience were participatory, shaped and led by a more expansive set of priorities than those of the governance and profit-oriented elite? It would be unrecognizable.

What models for survivance exist to contend with neoliberal necropolitics?58

Imagine if technoscience were participatory, shaped and led by a more expansive set of priorities than those of the governance and profit-oriented elite? It would be unrecognizable. To trace this vector of thought into political philosophy is to become ensnared in a matrix of uncomfortably overlapping ideologies: from intentional anarchist communities and the mutualism of marginalized leftist groups to free-market libertarians (dubbed “the hippies of the right” by Ayn Rand) and prepper utopias of motley flavors styled after Thoreau’s romantic notions of self-sufficiency in nature (that nonetheless overlooked its own foundation upon the genocide of Indigenous peoples). Here is a critical node. At stake in these political ideologies is negotiating uneasy boundaries between two fleshy abstractions: the individual and the multitude.

Mutual aid and philanthropy stretch the porous boundaries of the individual into a larger circumscribed group. They offer conditions of possibility, and networks of self-reliance and care. However, empathy and identification cannot scale up further to abstract swarms of anonymous social beings that make up disembodied, nationless humanity at large. This is the scale at which viruses think. This is the scale of being already multiple.

The scale of macroeconomics where global biomedicine interfaces with viral contagion is another critical node. My experience with hepatitis C demonstrates the urgency of advancing generalized transparency and policy to regulate drug pricing in the interests of public health. In 2013, news came of a breakthrough medication for hepatitis C. My doctors did not alert me, but instead I heard about it through a friend who is a medical journalist when she received a press release from a pharmaceutical company. The direct-acting antivirals eliminate up to 98 percent of HCV infections. The daily oral medications are well-tolerated and can effectively cure the previously lifelong disease within 8-24 weeks. The drugs inhibit viral replication, rapidly eradicating the virus from the human body. One might expect that the story would be all over the media: an innovative first! A drug that could effectively eliminate HCV in 71 million people worldwide. Absent from the headlines, the story was instead buzzing across the business and financial wires, accompanied by stock ticker symbols to entice investment. I burrowed through intellectual property and investing blogs for what negligible information I could retrieve about how patients might access the medication.

Gilead Sciences was the first to bring a cure to market, Sovaldi. It set the list price for a minimum course of treatment at an astonishing $84,000. A U.S. Senate finance report later found this price had no correspondence to patent, research, or manufacturing expenses.59

Instead, it was a deliberate strategy to establish a lucrative benchmark for the industry.60 Companies introducing similar cures for HCV have thus hovered near this price point. At this unwarranted and exorbitant price, Medicaid spent over $1.3 billion in 2014 to treat fewer than 2.4 percent of infections.61 The drugs can be manufactured for less than $100 per cure.62

One of the scientists attributed with the drug’s development worked together with the Nobel Prize-winning scientists who filed many patents on the discovery, genomics, and cell culturing of the hepatitis C virus, essential to research and drug development. Although patents are a major source of income for scientists and clearly played a role in keeping research within this close group of labs, he abdicated any responsibility for the commercial pricing of his innovations.63

Setting a price for the cure of HCV was the golden spike that has since emboldened pharmaceutical companies to accelerate ever higher prices for “life-saving” treatments and cures.64

No transparency or protocols in drug pricing are legally mandated, and no policies exist to ensure the public benefits from its own financial investments in research. When one primary market includes a pool of federal insurers who are legally barred from negotiating drug prices, pharma thus has the upper hand, with impacts upon health care costs worldwide.65

It is a myth that markets are unregulated for capitalist competition. Legal and political policies are firmly in place to ensure the mass transfer of public wealth from governments to corporations—such as grants for research—and also to ensure unrestricted monopoly pricing through patents, and laws that ban price negotiation. Unaccountable price hikes on existing medicines (such as insulin and EpiPens) have forced patients to self-ration medications and have led to many deaths. Since these scandals, the U.S. Senate Finance Committee has held hearings to make a show of berating top pharma executives. The executives emphasize the “complexity” in finding a price for life-saving drugs, while maintaining total opacity into their calculations. But pharma is clear on one point: they want to maintain independence from government intervention and international standardization in order to determine what they vaguely call “value-based” list prices for drugs. Meaning that a drug is priced to extract the maximum dollar its benefit is worth to customers: a life.

Against the outspoken objections of medical professionals who recommend treating HCV at any stage of the disease, the cost has forced insurers to ration drugs to the sickest patients. Hardly anyone can access the successful biomedical cure for hepatitis C. Curing HCV in the sickest does not reduce their risk of liver failure and cancer, which are exceedingly expensive to treat. It also does nothing to slow spread of a contagious viral infection hastened by the opioid epidemic. The most effective measures against the pervasive virus are to decriminalize addiction, lower drug costs, and treat everyone with the virus regardless of insurance status. Egypt, with some of the highest prevalence worldwide, has begun a mass testing and treatment program, and Scotland has followed this practice and eliminated HCV regionally.66

Global liver associations and the W.H.O. declared that strategic, worldwide elimination of the hepatitis C virus is logistically achievable—if only the medication is made affordable.

I was working as a researcher in Germany when the new drugs were approved. Germany has a mixed marketplace where public or private health insurance is mandated, but private insurers can deny coverage based on pre-existing conditions. However, the Affordable Care Act was going into effect in the U.S., which would be the first time in my adult life when I could not be denied health insurance. I contacted my hepatologist in the U.S. and he explained that, regardless of the new law, I would not be treated. The economic rationing of the cure was decided based on the extent of scarring in the liver, which meant that I did not qualify as sick enough. Evidence of a lifetime of disabling illness and deadly tumor markers were not the measures for the insurer’s rationing guidelines. He suggested I return to the U.S. where he would prescribe treatment. After what would certainly be several denials, I could then ask for patient assistance directly through Gilead, in a program originally designed to serve the uninsured (and which has since shut down). My doctor’s medical advice came permeated by the neoliberal ideologies of unregulated free markets: I was told to wait patiently several more years for the profit window to pass and hope that market competition would eventually resolve accessibility.

I called everyone I could: patient hotlines, doctors in the U.S., France, Germany, and Lebanon— even drug companies. In Germany, individual insurers negotiated the price with Gilead. Only France, with its single-payer public health system, was able to negotiate a somewhat lower price and receive rebates for cases that failed. I had no access to the capital required to pay for an $84,000 treatment out-of-pocket, but the undeniable privileges of being educated, white and multilingual facilitated my improbable plan B: I would attempt to obtain a residency visa in Germany, acquire mandatory health insurance, and find a doctor who would resist the price ration to treat me. It would take years, put me in debt, keep me 5,800 miles from family, and access was uncertain.

Back-up ideas included finding a way to purchase the drug in one of the countries where Gilead offers a 90% discount to public insurers. Even the discounted cost remains unrealistic for emerging economies. Unregulated online buyer’s clubs emerged, offering generics manufactured in India and China that could be ordered by mail for $800.67

Plan B was arduous and nearly forced me out of Germany when I was rejected by all private insurances due to pre-existing conditions. In March 2015, after months of battling immigration and medical bureaucracies, I was narrowly accepted into public insurance.

My doctor in Germany worried that if the insurance challenged his decision, they could demand reimbursement for the drugs and bankrupt his practice. But due to my low viral count, I was eligible for a shorter (cheaper) course of treatment. Insured, and thanks to German taxpayers, I paid 20€ out-of-pocket for two bottles of Gilead’s drugs. Each pill was priced at more than 30 times its own weight in gold.

On 1 May 2015, after two years of chasing access to the cure, I invited a few friends to be my lucky charms as I swallowed the first of the 1000€ pills with a glass of champagne. Just four weeks later, the virus was no longer detectable in my blood.

A few days after swallowing the last pill of the brief treatment, I woke in the morning with the exotic sensation of feeling rested and refreshed. Every other morning of my life, I tried to surface from beneath a deep weight of fatigue, despite 9-12 hours of uninterrupted sleep. The pain I had felt every day in my abdomen was gone. At 34 years old, I never knew what it was like to wake up in a healthy body without chronic viral infection, progressively destroying my liver and putting me at risk of premature death. Days before the New Year, my doctor called to confirm that my final blood tests showed no recurrence of the virus. I was definitively cured of my lifelong illness. Within a few years, my scarred liver would renew itself, and I would be at no greater risk of liver cancer.

The loneliness persists, however, as I am one among the mere 2-3 percent of people with HCV worldwide to have been treated.68

It is difficult for me to occupy this position of indebtedness and gratitude for the advancement of medical science to deliver such an astonishingly life-affirming possibility—amidst the deliberate abuse of public resources by the pharmaceutical industry, and the democratic governments that enable it to happen. There is no excuse for the immense privileges, international complexity and persistence it took for me to access the cure. It is beyond survivor’s guilt. As artist and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz said: “I’m carrying this rage like a blood-filled egg.”69

Inattention to the actuarial details of public health and biomedical innovation has put us in a precarious position now with respect to coronavirus. Gilead is continuing this pattern of speculative profiteering by resurrecting its failed HCV drug, remdesivir, for the COVID-19 market. The company received tens of millions of dollars in government grants to develop remdesivir. Nonetheless, at the start of the pandemic, they sought a special designation under a program for rare diseases to receive a seven-year monopoly on sales, tax credits, and expedited approval for the treatment of COVID-19. Following public outcry, Gilead rescinded this special designation and offered doses of the drug for experimental use in hospitals. The research of measurable benefits is minimal, but it appears remdesivir can reduce hospitalization due to COVID-19 by a few days in up to 47 percent of healthier patients. Gilead priced a course of treatment at $3,100, although they could break even at just $50. That is a profit margin of 98.4 percent. President Trump purchased the remaining global supply at this price for exclusive use in the U.S., preventing other countries from benefiting from the drug.70

Instances of exploiting the precarious conditions of the coronavirus pandemic are numerous in the biomedical sector. Vast sums of public funds are flowing from governments into research for treatments, diagnostics, and vaccines—as they should. But they do not serve public health without transparent accountability measures to ensure that outcomes will subsequently be made accessible and affordable to all.71

The United Nations Assembly adopted a resolution in May 2020 that called for COVID-19 treatments and vaccines to be treated as global public goods, but fell short of mandatory obligations or compulsory licensing that enables generics to be produced even when protected by patents.72

To better support policies of accessibility, medical students and researchers are tracking available data to map billions of dollars of public investments in coronavirus research.73

Peer pressure and grassroots campaigns such as Covax,74 Open Covid Pledge75 and Free the Vaccine76 have motivated many individual companies and institutions to voluntarily license their intellectual property to make innovations related to coronavirus freely available. Oxfam and UNAIDS organized an open letter signed by 140 world leaders and luminaries calling for a People’s Vaccine noting that, “Access to vaccines and treatments as global public goods are in the interests of all humanity. We cannot afford for monopolies, crude competition and near-sighted nationalism to stand in the way.” 77

All of these strategies nonetheless treat the coronavirus pandemic as a state of exception, leaving intact the structural inequalities of profit-oriented biomedicine.

All of these strategies nonetheless treat the coronavirus pandemic as a state of exception, leaving intact the structural inequalities of profit-oriented biomedicine. Policies to change patent law and drug pricing that favor public participation and the commons are essential measures needed for a paradigm shift away from neoliberal biopolitics. The virus is a vector that traces us into this critical node where sociality itself is at stake. The narratives we construct to identify obstacles in survivance beyond this pandemic must foreground the abundance of resources and biomedical expertise we collectively possess, and reject the narrative that biomedical innovation is only possible when the structures of predatory pharmaceutical profiteering and health disparities are maintained. We cannot cure racial capitalism or COVID-19 with breathwork and Zoom yoga and homegrown herbs and garbage bags cut into PPE. We must name as our commons what neoliberal biopolitics dispossess from the public, and we must be specific about it.

My bloodstream has been emptied of one its viral others, yet this porous relationality of being multiple in the world remains. Our vulnerable bodies are reliant upon each other at the planetary scale, requiring both the intimate care of mutual aid and the cures of biomedical science. To live among viruses and survive our interactions with them, think like a virus: xenophilic, opportunistic, multiplied and many. Our resistance to neoliberal isolation must become so expansive as to saturate the atmosphere.

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank the editors Sarrita Hunn and James McAnally for the invitation to write this essay, and for their generous engagement and patience through its mutations. Many thanks to Miriam Simun, Keturah Cummings, Patricia Reed, and Yun Ingrid Lee, the thoughtful readers of early drafts. I am grateful to the organizers, participants, and speakers within the Coronavirus Multispecies Reading Group, for exposure to a rich dialogue that pointed me towards some of the cited scholarship. With love and deep gratitude to my father, Gary.

Footnotes

- Flanagan, B. (2000). The Pain Journal . Los Angeles: Semiotexte/Smart Art Press.

- Elie, P. (2020, March 19). (Against) Virus as Metaphor. New Yorker.

- Throughout this essay, I use the pronoun “we” as a form of invitational address that is both inclusive and imprecisely defined by intention. While my concern and responsibility are for the health and wellness of all human assemblages across the globe, my concern is also that “we” do not all possess the same vulnerabilities or power in relation to viral infection or public health governance. My perspective, base of knowledge and subject matter are founded in the context of the settler colonial and extraterritorial empire-building infrastructures of the United States. My personal narrative is situated simultaneously within the privileges of citizenship, whiteness, class, and education, and the disadvantages of class, gender, queerness, and disability. I therefore ask for your patience, dear reader, at times when this “we” feels messy.

- “Biopower” and the derivative “biopolitics” are concepts coined by Michel Foucault about the modern state’s governance over the social body and its power to “let live” or “make die.” See: Foucault, M. (2007). Security, territory, population : lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-78 . (M. Senellart, F. Ewald, & A. Fontana, Eds.). Basingstoke ; New York: Palgrave Macmillan : République Française.

- Houghton, M. (2009). The long and winding road leading to the identification of the hepatitis C virus. Journal of Hepatology, 51 (5), 939–948.

- Wald, P. (2008). Contagious : cultures, carriers, and the outbreak narrative . Durham: Duke University Press.

- I have opted to use the colloquial “coronavirus” to mean SARS-CoV-2 throughout this essay. See: Gorbalenya, et al. (2020). Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: The species and its viruses – a statement of the Coronavirus Study Group. BioRxiv, 2020.02.07.937862.

- Although surveillance data is weak, annual deaths from HCV are a leading cause of death (surpassing HIV annually) and growing. In comparison to this already horrific figure of mass death, the World Health Organization reports over a million deaths due to COVID-19 at the time of writing in 2020. see: Cohen, J. (2017). New report halves the number of people infected with hepatitis C worldwide. Science . See this link and Flourish. (2020). Global Deaths Due to Various Causes and COVID-19. Retrieved September 26, 2020, from this link and Roth, G. A., Abate, D., Abate, K. H., Abay, S. M., Abbafati, C., Abbasi, N., … Murray, C. J. L. (2018). Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet , 392 (10159), 1736–1788. See this link

- Successful examples of patient advocacy are often rooted in the pre-existing sociopolitical coherence of intersecting identities. For example, awareness of and testing for sickle cell anemia was part of the Black Panther Party’s political organizing for Black liberation and against institutionalized racism in the U.S.; HIV activism was dominated by an already politically coherent demographic of white, gay, middle-class cis men in New York (to the representational exclusion of cis men of color, lesbian and trans communities that nonetheless co-organized and were greatly affected by the epidemic); or breast cancer awareness popularized by affluent, white feminist women with ties to corporate non-profits. Rabinow (1996) calls the formation of a collective identity in a shared, technoscientific biological experience “biosociality,” but he and Nikolas Rose (2007) argue that it is often grounded in other social bonds and identities such as race, class, and geography. See: Nelson, A. (2011). Body and soul the Black Panther Party and the fight against medical discrimination . (P. Muse, Ed.). London: University of Minnesota Press.; Rabinow, P. (1996). “Artificiality and Enlightenment: From Sociobiology to Biosociality,” in Essays on the anthropology of reason . Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.; and Rose, Nikolas. (2007). The politics of life itself. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- By neoliberal ideology, I am referring to the political practice and application of capitalist economic policies as they have manifested throughout specific histories and geographies, thereby in turn shaping subjectivation and the formation of the sense of self at the scale of culture. As Margaret Thatcher said, “Economics are the method, but the object is to change the soul.” As my essay writes an historical geography of personal narrative, it is informed in part by the global analysis of neoliberalism in: Harvey, D. (2007). A brief history of neoliberalism . Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

- What is health, what is care, and who wants it? These meta questions are beyond the scope of this essay. See generally Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. L. (2018). Care work : dreaming disability justice . Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press. *Thanks Yun Ingrid Lee for this reference.

- Davis, A. (2020, June 12). Uprising & Abolition: Angela Davis on Movement Building, “Defund the Police” & Where We Go from Here. Democracy Now!

- Gilmore, R. W. (2007). Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Helmreich, S. (2009). Alien ocean : anthropological voyages in microbial seas . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Wilkinson-Ryan, T. (2020, July 6). Reopening Is a Psychological Morass. The Atlantic.

- Robbins, J. (2018, April 17). Trillions Upon Trillions of Viruses Fall From the Sky Each Day. The New York Times.

- Starr, D. P. (1998). Blood: an epic history of medicine and commerce. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. and Waldby, C., & Mitchell, R. (2006). Tissue economies : blood, organs, and cell lines in late capitalism . Durham N.C.: Duke University Press.

- Reid, W. O. (1994). Blood donation and HIV. Canadian Medical Association Journal , 150 (10), 1541.

- Bogandich, W., & Koli, E. (2003, May 22). 2 Paths of Bayer Drug in 80’s: Riskier One Steered Overseas. New York Times.

- Evatt, B. L. (2006). The tragic history of AIDS in the hemophilia population, 1982-1984. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis , 4 (11), 2295–2301. And Rumi, M. G., Colombo, M., Gringeri, A., & Mannucci, P. M. (1990). High prevalence of antibody to hepatitis C virus in multitransfused hemophiliacs with normal transaminase levels. Annals of Internal Medicine, 112 (5), 379–380.

- On the death toll of HCV, see: Manos, M. M., W. A. Leyden, R. C. Murphy, N. A. Terrault and B. P. Bell (2008) Limitations of Conventionally Derived Chronic Liver Disease Mortality Rates: Results of a Comprehensive Assessment. Hepatology 47(4): 1150-7.; St. John, T. M. and L. Sandt (2005) The Hepatitis C Crisis. Ethnicity & Disease. 15(2): S2,52-S2-57.; and World Health Organization. (2018, May 24). The top 10 causes of death.

- Amon, J. J., Garfein, R. S., Ahdieh-Grant, L., Armstrong, G. L., Ouellet, L. J., Latka, M. H., … Williams, I. T. (2008). Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus Infection among Injection Drug Users in the United States, 1994-2004. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 46 (12), 1852.

- The presence of other venereal diseases that cause open wounds, or engagement in sexual practices that may involve contact of fresh, infected blood directly entering the bloodstream of a partner are the circumstances under which transmission may occur. Medical literature tends to identify risk categories with moralizing and imprecise generalizations, such as “non-monogamous” sexual practices, men who have sex with men, etc., without specific reference to what are safer sex practices for this blood-borne virus. See: Terrault, N, J. Dodge, E. Murphy, J. Tavis, A. Kiss, T. Levin, R. Gish, M. Busch, M. Reingold, and M. Alter. (2013) Sexual Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus Among Monogamous Heterosexual Couples: The HCV Partners Study. Hepatology 2013;57:881-889.

- The Sackler Family is most identifiable among them for their support of art institutions that bear their name. Other companies include Purdue Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, the McKesson Corporation. See: Church D, Barton K, Elson F, DeMaria A, et al. (2011) Notes from the field: risk factors for hepatitis C virus infections among young adults – Massachusetts, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR ). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011.; Glazek, C. (2017, November). The Secretive Family Making Billions From the Opioid Crisis. Esquire Magazine; Meier, B. (2018, May 29). Origins of an Epidemic: Purdue Pharma Knew Its Opioids Were Widely Abused. New York Times; and Volkow, N. (2015) American’s Addiction to Opioids: Heroin and Prescription Drug Abuse. NIH Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control, May 14, 2014.

- Fleckenstein, J. (2004) Chronic Hepatitis C in African Americans and Other Minority Groups. Current Gastroenterology Reports 2004, 6:66–70. and Bruce, V., Eldredge, J., Leyva, Y., Mera, J., English, K., & Page, K. (2019). Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Indigenous Populations in the United States and Canada. Epidemiologic Reviews, 41 (1), 158–167.

- See generally: Alexander author, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow : mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York: New Press.; Davis, A. (2016). Freedom is a constant struggle : Ferguson, Palestine, and the foundations of a movement. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books.; and Gilmore, R. W. (2007). Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California by R.W. Wilson . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Daniels, A. M., & Studdert, D. M. (2020). Hepatitis C Treatment in Prisons — Incarcerated People’s Uncertain Right to Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy. New England Journal of Medicine, 383 (7), 611–613.

- Jones, A. (2017, January 6). Activists hail judge’s decision to provide hepatitis C drug to Mumia. Philadelphia Tribune, p. 1.

- Washington, H. A. (2006). Medical apartheid : the dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from colonial times to the present. New York: Harlem Moon. and Williams, D. R., & Cooper, L. A. (2020, June 23). COVID-19 and Health Equity – A New Kind of “herd Immunity.” JAMA – Journal of the American Medical Association . American Medical Association. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.8051

- Hardeman, R. R., Medina, E. M., & Boyd, R. W. (2020). Stolen Breaths. New England Journal of Medicine , 383 (3), 197–199. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2021072

- Roser, M., Ritchie, H., Ortiz-Ospina, E., & Hassell, J. (2020). Excess mortality during the Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) – Our World in Data. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from https://ourworldindata.org/excess-mortality-covid

- Haraway, D. J. (2008). When Species Meet . University of Minnesota Press. and Townsend, A. K., Hawley, D. M., Stephenson, J. F., & Williams, K. E. G. (2020). Emerging infectious disease and the challenges of social distancing in human and non-human animals. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences , 287 (1932), 20201039. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.1039

- Hedva, J. (2020). Sick Woman Theory. Retrieved from http://johannahedva.com/SickWomanTheory_Hedva_2020.pdf

- Also produced naturally in the body to fight viral infections like the flu, and currently being tested for use against COVID-19.

- Some context about health insurance in the U.S.: Prior to the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 in the U.S., health coverage was not available on the free market, but rather mostly accessible only as a benefit from employers to its full-time employees. Without the employer subsidy, health insurance premiums were largely unaffordable unless people lived in states that offered the state-subsidized health coverage called Medicaid, and met poverty guidelines to qualify for it. My father was a civil servant for the county and state of California, and I was covered as a dependent under his health insurance until I graduated from college. After this, a full-time job with benefits was the only way to access healthcare, because health providers could refuse to cover people with pre-existing conditions until this practice was banned by the ACA. The Supreme Court will hear arguments to overturn the ACA on 10 Nov 2020, which if accomplished, will result in large tax cuts for the extremely wealthy. See: Gleckman, H. (2020, May 12). By Overturning The ACA, The Supreme Court Would Cut Taxes Substantially For High-Income Households. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/howardgleckman/2020/05/12/by-overturning-the-aca-the-supreme-court-would-cut-taxes-substantially-for-high-income-households/

- Representation in clinical trials, and therefore the data extrapolated from them, often follows patterns of demographic privilege. Requirements for enrollment in the clinical trial speaks to the many privileges I already possessed: I had to be under the regular care of a specialist who would share information that clinical trials existed; I had to have the education and organizational capacity to research and find clinical trials independently; I had to live in the vicinity of a research hospital, which tend to be concentrated in urban centers with elite universities; I had to have enough money and the flexibility of time to cover my travel to and from the hospital; I had to be relatively healthy without extreme liver scarring (cirrhosis); I could not have undergone previous treatment for HCV; I could not actively drink alcohol or be dependent upon illicit drugs, which excludes the majority of people with HCV; I had to be dependable to self-administer a weekly syringe; I had to be insured to cover the doctor’s visits, or wealthy enough to pay out-of-pocket.

- Anderson, R. (2014, November 6). Pharmaceutical industry gets high on fat profits – BBC News. BBC News . https://www.bbc.com/news/business-28212223

- Ewing-Nelson, C. (2020, June). Despite Slight Gains in May, Women Have Still Been Hit Hardest by Pandemic-Related Job Losses. National Women’s Law Center . https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/May-Jobs-FS.pdf

- Ramsey Pflanzer, Lydia. (2020, 22 September). We just got a look at how health insurance startups like Oscar, Clover, and Bright fared through the early months of the coronavirus pandemic. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/health-insurers-oscar-clover-bright-devoted-second-quarter-2020-results-2020-8

- In the U.S. some call this single-payer coverage “Medicare-for-all.” Medicare is currently available only to people above the age of 65 and with certain disabling health conditions.

- “I went to the Indian Health Services to fix a tooth, a complicated pain. Indian health care is guaranteed by treaty but at the clinic limited funds don’t allow treatment beyond a filling. The solution offered: Pull it. Under pliers masks and clinical lights, a tooth that could’ve been saved was placed in my palm to hold after sequestration… the root of reparation is repair. My tooth will not grow back. The root, gone.” Long Soldier, L. (2017). Whereas : poems . Minneapolis, Minnesota: Graywolf Press.

- Bach, P.B. (2019, January). Prepared statement in United States Senate Committee on Finance. Drug Pricing in America: A Prescription for Change, Part I, S. HRG. 116–267 . Retrieved from https://www.finance.senate.gov/hearings/drug-pricing-in-america-a-prescription-for-change-part-i and Kesselheim, A. S., Avorn, J., & Sarpatwari, A. (2016). The High Cost of Prescription Drugs in the United States: Origins and Prospects for Reform. JAMA , 316 (8), 858–871. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.11237

- Bach (2019, January), Op. cit.; Freeman, J. A. D., & Hill, A. (2016). The use of generic medications for hepatitis C. Liver International , 36 (7), 929–932. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13157 ; and Yu, N. L., Helms, Z., & Bach, P. B. (2017). R&D Costs For Pharmaceutical Companies Do Not Explain Elevated US Drug Prices. Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20170307.059036/full/

- Lazard, C. (2018). CRIP TIME. https://www.artforum.com/film/lizzie-homersham-on-carolyn-lazard-s-crip-time-2019-83007 and Samuels, E. (2017). Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time. Disability Studies Quarterly , 37 (3). Retrieved from https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/5824/4684 *Thanks Sarrita Hunn for this reference.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/05/health/nobel-prize-medicine-hepatitis-c.html

- Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 569 U.S. 576. (2013, June 13). Retrieved from https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/12pdf/12-398_1b7d.pdf On innovation policy and patent law, see generally: Kleinman, Daniel Lee. 1995. Politics on the Endless Frontier: Postwar Research Policy in the United States. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. and Parthasarathy, Shobita. (2017.) Patent Politics: Life Forms, Markets, and the Public Interest in the United States and Europe. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Berrigan, C. (2012). The Life Cycle of a Common Weed: Viral Imaginings in Plant-Human Encounters. WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly , 1 – 2 (1–2), 97–116. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23333438 and Berrigan, C. (2014). Life Cycle of a Common Weed. In S. E. Kirksey (Ed.), The Multispecies Salon . Durham: Duke University Press.

- Cited in Berrigan (2012), Op. cit.: Dalsgaard, S. (2007). ‘I Do It for the Chocolate.’ Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory , 8 (1), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/1600910x.2007.9672941

- Engel, J. (2006). The epidemic : (a global history of AIDS) . New York: Smithsonian Books/Collins. and Nelson, A. (2011). Body and soul the Black Panther Party and the fight against medical discrimination. (P. Muse, Ed.). London: University of Minnesota Press.

- The Black Doctor Covid-19 Consortium (2020, May 3). Bloomberg News. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2020-05-03/the-black-doctor-covid-19-consortium-video

- On these tensions and provocations, see generally: Hobart, H. J. K., & Kneese, T. (2020). Radical Care: Survival Strategies for Uncertain Times. Social Text , 38 (1 (142)), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-7971067 and Martin, A., Myers, N., & Viseu, A. (2015). The politics of care in technoscience. Social Studies of Science , 45 (5), 625–641. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.library.nyu.edu/stable/43829049

- Butler, J. (2015, November 15). Precariousness and Grievability—When Is Life Grievable? Verso Books Blogs. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/2339-judith-butler-precariousness-and-grievability-when-is-life-grievable

- See arguments in United States Senate Committee on Finance. (2019, February). Drug Pricing in America: A Prescription for Change, Part II, S. HRG. 116–39 . Retrieved from https://www.finance.senate.gov/hearings/drug-pricing-in-america-a-prescription-for-change-part-ii

- Gokey, T. (2020, September 17). I volunteered to be a human guinea pig for a Covid vaccine. Now I’m having second thoughts. The Guardian .; Haraway, D. (2008), Op. cit.; and Kirksey, E. (2020). The Mutant Project : Inside the Global Race to Genetically Modify Humans. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

- Brooks, B. W., & Huggett, D. B. (2012). Human pharmaceuticals in the environment : current and future perspectives. New York, NY: Springer.; Dietrich, A. S. (2013). The drug company next door pollution, jobs, and community health in Puerto Rico. (P. Muse, Ed.). New York: New York University Press. *Thanks Adriana Garcia Lopez for this reference.; and Eban, K. (2019). Bottle of lies : the inside story of the generic drug boom . New York, NY: Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

- Chang, A. Y., Cowling, K., Micah, A. E., Chapin, A., Chen, C. S., Ikilezi, G., … Dieleman, J. L. (2019). Past, present, and future of global health financing: a review of development assistance, government, out-of-pocket, and other private spending on health for 195 countries, 1995–2050. The Lancet , 393 (10187), 2233–2260. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30841-4

- Kaiser, J. (2018). NIH gets $2 billion boost in final 2019 spending bill. Science . https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/09/nih-gets-2-billion-boost-final-2019-spending-bill and as cited in Mitchell, D. (2019, July 26). Oral Statement, United States House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform. (2019). The Patient Perspective: the devastating impacts of skyrocketing drug prices on American families, Serial No. 116–55 . United States House of Representatives. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-116hhrg38320/pdf/CHRG-116hhrg38320.pdf

- Achille Mbembe’s “necropolitics” expands upon Foucault’s “biopolitics” to account for states of exception, the colony, and the plantation. See: Mbembe, A. (2019). Necropolitics . (S. Corcoran translator, Ed.). Durham: Duke University Press.

- United States Senate Committee on Finance. (2015, December). The price of Sovaldi and its impact on the U.S. health care system / prepared by the staffs of ranking member Ron Wyden and committee member Charles E. Grassley. Retrieved from http://purl.fdlp.gov/GPO/gpo63792 Executive summary: http://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/11%20SFC%20Sovaldi%20Report%20Executive%20Summary.pdf

- This list price was the baseline, but costs could be more or less depending upon the country, insurer, and length of treatment. See: Roy, V., & King, L. (2016). Betting on hepatitis C: how financial speculation in drug development influences access to medicines. BMJ : British Medical Journal (Online) , 354 . https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3718

- U.S. Senate Committee on Finance (2015), op. cit.

- Hill, A., Khoo, S., Fortunak, J., Simmons, B., & Ford, N. (2014). Minimum Costs for Producing Hepatitis C Direct-Acting Antivirals for Use in Large-Scale Treatment Access Programs in Developing Countries. Clinical Infectious Diseases , 58 (7), 928–936. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu012

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/inventor-of-hepatitis-c-cure-wins-a-major-prize-and-turns-to-the-next-battle/

- Johnson, C., Dennis, B. (2015) How an $84,000 drug got its price: ‘Let’s hold our position … whatever the headlines’. Washington Post: Dec 1, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/12/01/how-an-84000-drug-got-its-price-lets-hold-our-position-whatever-the-headlines

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). Making medicines affordable: A national imperative . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.17226/24946 .

- Waked, I. et al. (2020). Screening and treatment program to eliminate hepatitis C in Egypt. New England Journal of Medicine , 382 (12), 1166–1174. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1912628 and (July 27, 2020 Monday). NHS Tayside claims it has ‘effectively eliminated’ hepatitis C. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-tayside-central-53558315

- Gahlot, M. and Gargoullaud, C. (2019). Buyer’s Club. BBC News. https://www.theguardian.com/news/ng-interactive/2019/jun/03/buyers-club-the-network-providing-people-with-affordable-hepatitis-c-medicine-video

- World Health Organization. (2018, March). Progress report on access to hepatitis C treatment: focus on overcoming barriers in low- and middle-income countries, March 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260445/WHO-CDS-HIV-18.4-eng.pdf

- Wojnarowicz, D. (1991). Close to the knives : a memoir of disintegration . New York: Vintage Books.

- Tiffney, T. (2020, July 20). Americans are paying twice for remdesivir. Slate . https://slate.com/technology/2020/07/remdesivir-covid19-treatment-gilead-price.html

- Endless Frontier Act Press Release (2020, May 27). https://khanna.house.gov/media/press-releases/release-khanna-schumer-young-gallagher-unveil-endless-frontier-act-bolster-us ; Brennan, Z. (2020, July 13). Vaccine-makers’ ‘no profit’ pledge stirs doubts in Congress. Politico . https://www.politico.com/news/2020/07/13/vaccine-makers-profit-congress-360135 ; and Lerner, S. (2020, July 1). Trump Administration Waived Coronavirus Price Protections. The Intercept . https://theintercept.com/2020/07/01/coronavirus-treatment-drug-contracts-trump/

- United Nations. (2020). COVID-19 response, A73/CONF./1 Rev.1 . https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA73/A73_CONF1Rev1-en.pdf

- Not all grants are made public, so this cannot be used as a definitive measure of the totality of public investments in COVID-19 research. See: https://www.publicmeds4covid.org/

- https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/covax-explained

- https://opencovidpledge.org/

- https://freethevaccine.org/

- Oxfam International. (2020). OPEN LETTER: Uniting Behind A People’s Vaccine Against COVID-19 | by Oxfam International. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@Oxfam/uniting-behind-a-peoples-vaccine-against-covid-19-87eec640976

Caitlin Berrigan works across performance, video, sculpture and text to engage with the intimate and embodied dimensions of power, politics and capitalism. Her early works from 2006-2010 addressed viruses, spatial choreographies of contagion, medicine, and care. Her recent work, Imaginary Explosions was part of the Berlinale Forum Expanded exhibition (2020), the subject of a solo show at Art in General, New York (2019), and an artist’s book with Broken Dimanche Press, Berlin (2018). Her work has been shown at the Whitney Museum, Poetry Project, Henry Art Gallery, Harvard Carpenter Center, Anthology Film Archives, and UnionDocs, among others. She has received grants and residencies from the Humboldt Foundation, Skowhegan, Graham Foundation, and Akademie Schloss Solitude. She holds a Master's in visual art from MIT and a B.A. from Hampshire College. She taught emerging media full-time at NYU Tisch and is a Visiting Professor at Bard College Berlin. She is an artist, writer, and researcher affiliated with the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and NYU Technology, Culture and Society.