From “Our House is on Fire” to Climate Justice Code Burnout

Valentina Vella

December 2020

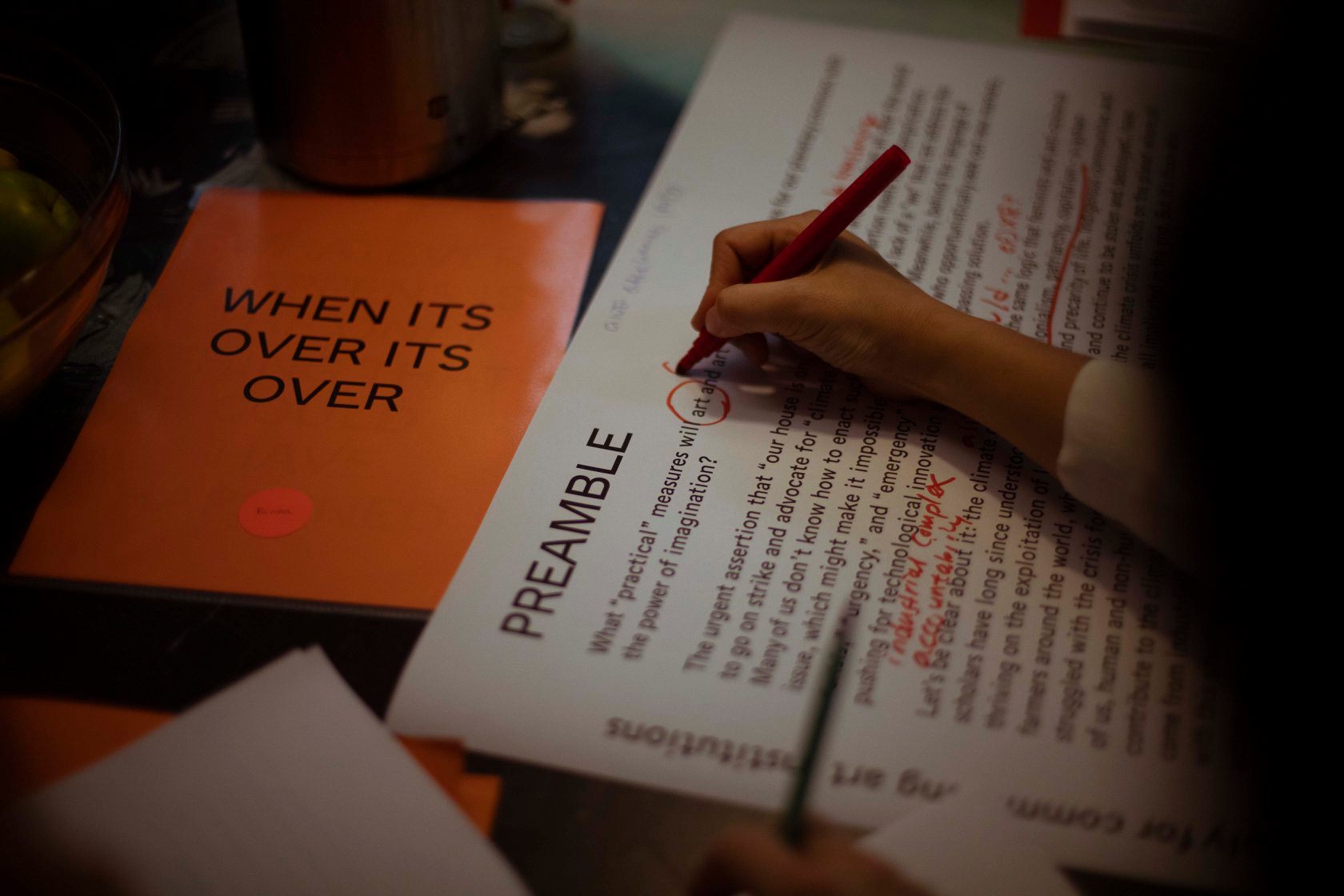

Photo by Martha Stroo courtesy of Casco.

When we convened in Utrecht for the two-day second assembly, “Our House is on Fire,” last fall (October 25-26, 2019), less than a year had passed since the first assembly, “Elephants in the Room” (November 2018), facilitated by Casco Art Institute: Working for the Commons (from now on referred to as Casco). The first assembly had been about foregrounding reproductive labor, presenting non-capitalist practices, and a collective attempt at re-thinking the work of artists and art organizations in the Dutch art ecology and beyond. It had confronted us with the uncomfortable fact that even in the arts sector people end up upholding neoliberal, colonial, patriarchal thinking in their professional and personal lives. Most of us chose this field out of love and a desire to be “free” from alienating work, only to find ourselves years later in what often amounts to an abusive relationship – powerless and subjected to the same diktats we thought we had so cleverly escaped.

The first assembly started by asking what I believe are the right questions: What if we could actually fix this? What if we could design a new art world and new art institutions that wouldn’t reproduce violent neoliberal pressures? We are used to artists, theorists and collectives advocating for a new way of doing things, but institutions, largely because of inherent power dynamics, financial ties, and work habits that are hard to unlearn, are usually not willing to completely reassess the way they function, even when they nominally espouse radical theories.

Building on Casco’s research trajectory on the commons and its experience as a member of Arts Collaboratory, the first assembly ended up being mostly about presenting something – a prefiguration of what art and art institutions could be (a different way of living, working and organizing) rather than about making decisions together. In other words, ultimately it still felt like a symposium. Last fall, however, the second assembly graduated to full ‘assembly-hood’ in its ambition to engage in an urgent, practical matter: the collective editing of a Climate Justice Code drafted before the assembly by an editorial committee including Thomas de Groot and Taru Aitola from Commons Network; Joram Kraaijeveld from Platform BK; Teresa Borasino and Harriet Bergman from Fossil Free Culture NL; Selçuk Balamir from Code Rood; independent artists Clementine Edwards and Annette Krauss; researcher and organizer Ying Que; and Binna Choi, Yolande van der Heide and Rosa Paardenkooper from Casco Art Institute.

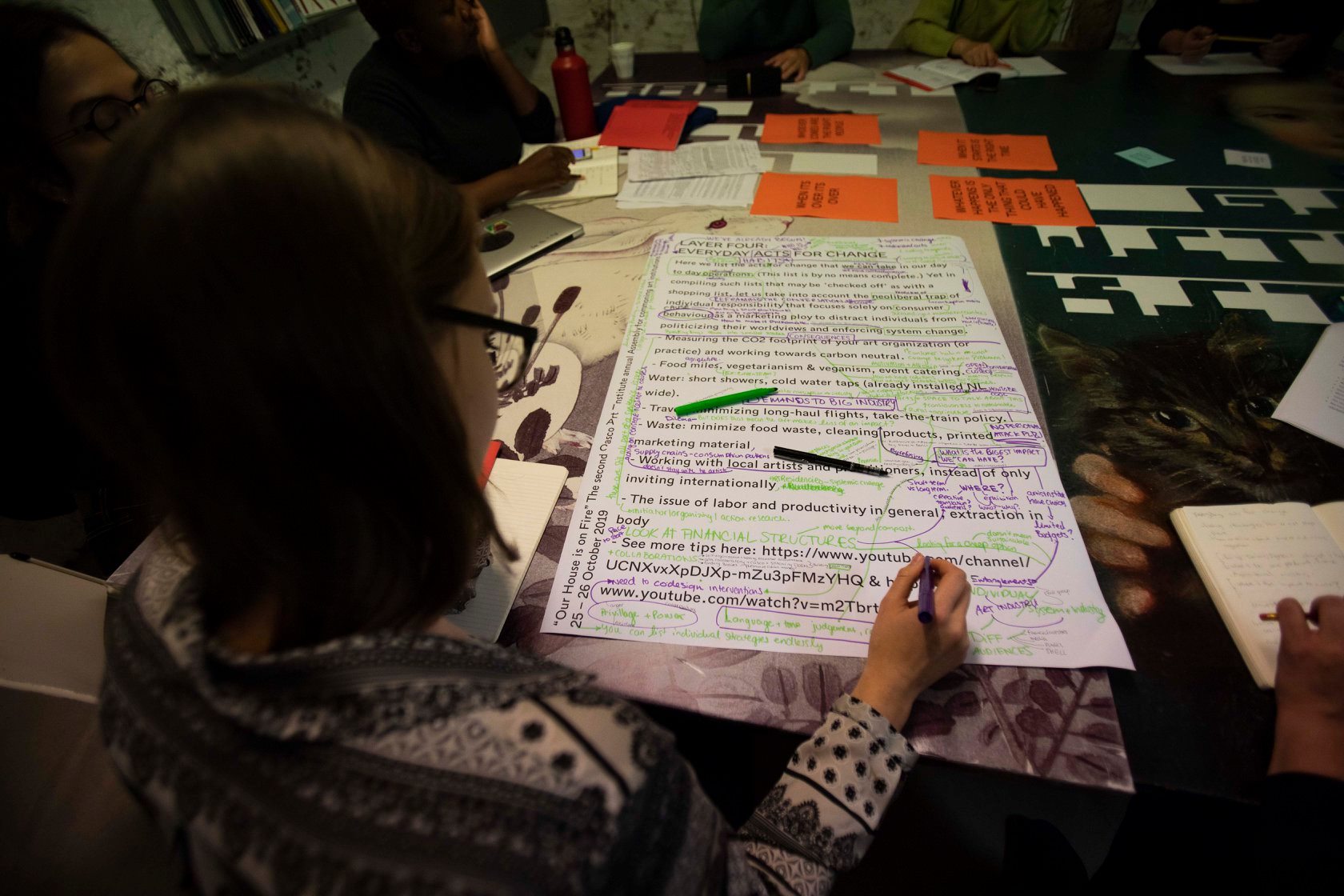

Photo by Martha Stroo courtesy of Casco.

The Climate Justice Code is meant to be written as a statement of intent that could be adopted by artists and art organizations (like the Fair Practice Code) and ultimately function as a policy tool. The event framed the climate crisis as the predictable result of the hegemonic imperialist-patriarchal-capitalist forces which have been oppressing and killing people and non-human animals for centuries and an emergency we need to collectively practice against. As such, this Climate Justice Code writing experiment positioned itself in a radical tradition advocating for systemic change. The code consisted of a Preamble (titled “What “practical” measures will art and art institutions take to care for our planetary commons with the power of imagination?”) and seven “layers” (Commons as a framework; A definition of climate justice; Art as an essential, alternative tool to climate crisis; Everyday Acts for Change; and Advocacy: Dis(engage) from Big Industry). It is important to note that all the people who participated in the first assembly had been invited to join the editorial committee a few weeks before the second assembly.

“Our House is on Fire” included moments of formal learning and reflection (keynotes and presentations), but most of the time was allocated to the collective editing experiment. Some of the language in the code seemed to imply that artists and art institutions need to take a backseat and act as accomplices of other (i.e. Indigenous, queer, POC, feminist, environmentalist) movements that already exist, rather than trying to reinvent activism from scratch or erasing the work that has been done so far. Yet, the art ‘layer’ had a more optimistic tone and seemed to assign a fundamental role to art, which was later questioned in the open session.

The first draft also problematized the ‘natural’ leadership of Greta Thunberg in the climate justice movement. While her “Our House Is On Fire” speech is echoed in the title of the assembly itself, the Code makes a point of mentioning that some people’s houses have been on fire for at least five hundred years. As some of the presentations addressed these political issues directly, I will start by summarizing them here.

The presentations by Arts Collaboratory members (a translocal ecosystem of twenty-five organizations situated in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and The Netherlands that focuses on art practices, processes of social change, and working with communities beyond the field of art) informed us about complementary sides of the struggle. We learned about work happening in Bolivia, Mexico and Indonesia, where activism often means putting one’s life at risk, but also where strategies of resistance have been refined over many years, especially regarding the role that art can have in political movements. An interesting tool shared by KUNCI Study Forum & Collective is the Environmental Justice Atlas, which shows existing environmental justice collectives and organizations on a global map.

Writer and pleasure activist Ama Josephine Budge deepened our understanding of the very different ways vulnerable populations and the Global South are affected by global warming. Even movements like Extinction Rebellion (XR) have so far used strategies such as focusing on getting arrested during demonstrations (which is a relatively safe experience for a white person, but can mean violence and/or deportation for everyone else) and have refused to learn from the truly intersectional or Indigenous movements which have been doing this sort of thing for ages. The centering of the cis white male body in political, theoretical and artistic discourse is not a neutral fact, and it can be actively challenged by resisting visual archives that make non-white bodies and their struggles and achievements invisible. She added that part of this project is also about questioning white temporalities – meaning not only the linear Western conception of time, but also the idea that what we are talking about (and trying to imagine) is a future that the dispossessed and vulnerable are already living, a future that XR envisions as a threat.

Suzanne Dhaliwal defines herself as an activist who is simultaneously fighting the climate crisis and fascism. She was involved in campaigns against unconventional oil extraction and destruction of Indigenous lands in Canada, and she got fired from NGOs for saying uncomfortable things. She has worked on actions that are designed to have a strong visual and conceptual impact that attract a lot of attention (such as undermining corporate funding channels and creating brand damage) without hurting vulnerable communities. She contests the term Anthropocene and only half-jokingly says that we should use the term “Whitesupremacene.” She consults the communities she works with instead of imposing strategies from above and also works on how to avoid recreating toxic patterns in activist groups. Like Ama, she is very critical of XR.

Ugo Mattei (appearing to us as a big head on a screen sitting under a drawing of the sun made by his daughter) is a jurist and activist and a seminal figure in the movement for the commons and against the privatization of water in my natal city of Rome. He explained that while the commons has always existed, the law has erased it: it only distinguishes between private and public property. In other words, the commons has been plundered and turned into capital. The Rodotà Commission in 2007 tried (and failed) to put the commons back into the civil code in Italy, defining it “as all goods functional to the development of the human personality.” He explained that legal trials are designed to have a binary outcome (a winner and a loser), but asked us to imagine a third option such as ruling in the interest of a third party: future generations.

Today our laws openly support capitalism. Yet, while it tends to be an authoritarian tool of the government which favors corporations, people can challenge it, resist it and reclaim it for themselves. Capitalism isn’t an immutable, god-like entity. We have a fundamental right to resist the laws that threaten us through petitions and civil disobedience. For example, universal basic income could reverse the material and cultural landscape because of its emancipatory potential. There are also ways to turn capital back into commons by, for example, public shareholding (where one person equals one share) in corporations that work for the commons (such as the one he founded, Dolphin Corporation, now operating as Serrala) and operating an ecological reconversion of the economy.

You can listen to these keynotes on the Assembly’s Soundcloud.

The Collective Editing Experiment

The Code was collectively edited through Open Space principles inspired by Occupy assemblies. The Four Open Space Rules state:

- Whoever comes are the right people.

- Whatever happens is the only thing that could have.

- Whenever it starts is the right time.

- When it’s over, it’s over.

People were invited to spontaneously join one of the ‘layers’ (the name derives from the image of an onion, which would be later abandoned in favor of kombucha), keeping in mind that at this stage ‘hovering’ and moving around is encouraged. We also used hand signals to quickly communicate our feelings about edits/proposals.

I decided to focus on the ‘art layer’ which included about ten artists around a table and was facilitated by Annette Kraus. We immediately found many problems in the text. To start with, the definition of art it proposed seemed narrow to many of us.

Art as an Essential, Alternative Tool for Climate Crisis

Artists and art institutions produce and present artworks that emphasize or bring value to certain ideas. They play an inherent role in the production of our reality.

Art is the domain for radical imagination: the ability to imagine the world, life and social institutions not as they are but as they might otherwise be or become.

Art is well-placed to recognise what is at stake in the call to organize for systemic change. When speaking about system change, art is crucial for envisioning and practicing an alternative.

Is art really about ideas? Then in what ways is it different from philosophy? How can we include the body in this text? Is art really special or alternative? Alternative to what? Are we talking about art qua art? Or is only explicitly political art considered a worthy activity in the context of climate justice?

In the second session, some observations focused on how art is simply another industry in the context of financial capitalism, as implicated as other more obvious industries. Others observed that the art world represents a small percentage of the art practices that currently exist and that are available to be mobilized. Perhaps this document is more about potential than the current state of things? There is also the issue of the (in)visibility of certain practices that are maybe already doing what we wish art could do, but are simply not widely accessible.

In the plenary session we attempted a digital harvest with facilitators reporting about individual layers. I can’t convey the entirety of that informative discussion, but some of the questions raised were: If the commoning structure supposedly “doesn’t presume any specific politics,” how can we make sure that we’re maintaining a decolonial, feminist perspective? Why insist on using the word “alternative” since art is far from being an alternative to anything right now?

Disability justice was proposed as a resource to look into when thinking about small everyday actions we can engage in. There was also discussion around the necessity of de-centering the self and acting from a place of service. The conversation continued to consider the need for face-to-face conversations when engaging with the Code (not simply adding it to one’s email signature), the difference between responsibility and accountability (the necessity to actually change one’s practice and to communicate it clearly), mapping finances and being clear about one’s environmental impact.

What about radical slowness? A personal story was shared about rejecting oil money for a commission. What are the alternatives to this sort of funding? Should you take the money and do something good for it, or reject it altogether as a political act of dissent?

The image of an onion was seen as a good metaphor since all layers are connected and the skin (which here is the Preamble) was also once the core. But is the metaphor of kombucha a better one? Something that can be disseminated from a mother, infinite scobies spreading healthy bacteria and yeasts into the world?

Ying Que facilitated the session like a pro. Ama was very vocal about the necessity of adding a ‘reparations layer.’ This part of the Code would many months later become known as “Reparations, Rematriation and Repair,” the centerpiece of the document, a much needed recognition that Climate Change has largely been caused by colonization and imperialism, and that the only possible future for this planet entails a commitment to undo and repair centuries of European oppression, murder and theft.

There were many questions in search of an answer: Who is the “we” in the Code? How are the people in the physical Assembly not replicating normativity, but opening a dialogue – like a letter sent out into the world? What is the responsibility of us, the writers? Do we hold people accountable? Or do we focus on dispersing this into the world?

In the last breakout session on the ‘art layer’ we were mostly artists and curators. We had a big piece of paper full of all the comments we had been writing since the first session. We struggled to keep track of comments while summarizing, focusing and honing in. Many good arguments were lost in the process. We agreed to swap some terms so that “climate crisis” became “climate justice,” and “alternative” became “effective.” What else does art do though? Some of us wanted to introduce terms like “defamiliarize,” “question” and “challenge.”

We also wanted the text to mention how art can map new relationships to the body, that it doesn’t simply present “ideas,” which sounds very disembodied. We wondered whether we should incorporate a critique of what the art world is – or focus on the future, the potential? We engaged in a collective effort to imagine a kinder art community.

The “final text” of the ‘art layer,’ a compromise between different viewpoints and suggestions (which doesn’t give justice to the plurality of insights) ended up reading:

Art for Climate Justice

Artists, art institutions and artistic practices emphasize or bring value to ideas.

They play an inherent role in the production of our realities.

Art is the domain for radical imagination: the ability to imagine the world, life and institutions not as they are but as they might otherwise be or become.

Thus, art is well-placed to recognize what is at stake in the call to organise for systemic change. When speaking about system change, art is crucial in recognising existing practices/interventions and envisioning possibilities/proposals for climate justice.

At this stage, I sometimes felt like the existence of a first draft limited us. I wondered what we would have come up with if we had started from scratch, especially when discussing what art is and could be for us. A good question that came up in the plenary session was whether the Code was a policy instrument or a poetic statement. (Personally, I think it could be both, but I am not known for being a practical person.)

Someone suggested that the ‘reparations layer’ seemed like an add-on and that it was sidetracking, which provoked a firm response from some people of color in the room, led by Ama Josephine Budge and Suzanne Dhaliwal. Visibly upset, they said that they were doing all the emotional labor and they couldn’t bear it anymore: There’s a million of these codes already! Don’t we want this one to be different? To do the right thing? We all agreed to leave the layer there.

Someone else worried about the potential capturing of the Code. How do you avoid it getting subsumed? Turned into a product? We discussed some practical steps to spread the Code, its implementation and strategy. We can’t abandon the baby! Perhaps we could develop a toolkit for making assemblies? A proposal focused on BIPOC issues consisted of creating accountability bodies, a system to help institutions implement the Code and at the same time hold them accountable in exchange for a fee that would cover the labor of educating them. We agreed that further editing of the Code was needed.

In this iteration at the end of the “Our House Is On Fire” assembly, the Code highlighted the way the art world (from big museums and collectors down to the smallest individual art practice) is often implicated in violent processes. It refused to see art as an ethereal realm insulated from the real world and proposed that art’s energetic and creative potential could (and should) be harnessed. Once the Earth is understood as a ‘planetary commons,’ it makes sense to establish a set of guidelines in order to take care of it collectively—as a practice that underlies and sustains all other practices. Still: How does one go about writing such guidelines together? How to make a hundred people in a room agree on every word? Not to mention: How to get many artists and art institutions to adopt the Code as their own?

It is difficult to rewrite a document together – many brains attempting at once to clarify to themselves what they think, communicating it to others effectively, and finding ways to discuss and negotiate. Introverts and people who don’t feel confident enough to speak in a big group tend to stay silent. What kind of strategies could we have devised to keep the space truly open to everyone and also to take care of everyone’s emotional and bodily needs? Did we need more breaks, more moments to rest and recover?

Photo by Martha Stroo courtesy of Casco.

At the end of our two-day marathon we had gone an hour overtime and had had to cancel the collective pot experiment which would have been led by Yin Aiwen. While the first assembly had ended on a festive note, “Our House is on Fire” ended with the expression on most people’s faces like: Don’t talk to me. I want to go home and take a long bath. (If only Dutch minuscule apartments had baths!)

At this stage, the Code focused on what is wrong with the world, but didn’t describe the future we want to live in. It made general statements about art’s function, prescribed more ethical behavior and pointed vaguely to commoning practices as a way forward. Maybe what I wish it could be is a manifesto or a pamphlet, rather than a Code, but I believe it is easier to win support and galvanize action by painting a vivid picture of a better world than by listing a set of moral guidelines. I think this piece of collective writing is missing a visionary touch, infused with joy.

Editing Update (February 2020)

We have been editing (or rather rewriting) the Code for a while. The “we” in this case are part of the group that attended the “Our House is on Fire” assembly last October. Fewer than ten people were at the two meetings that were held since the assembly; however, the group that is still at least nominally involved with this endeavor is bigger (about forty people). We plan on opening up this process to others through workshopping the Code at specific events and by simply giving a link to the document to anyone who might be interested.

Instead of just integrating comments into the original post-assembly draft, the work has consisted of further problemitizing it. Everything is being questioned and rewritten. I have enjoyed working in smaller groups and have attempted a complete rewrite of two layers (art and commons) using the comments harvested during the assembly, books I am currently reading (such as Silvia Federici’s Re-enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons and Massimo De Angelis’ Omnia Sunt Communia), online lectures by art sociologist Pascal Gielen, personal intuitions and conversations with fellow Code editors (Alessandra Saviotti, Nicole Jesse, Zoe Scoglio, Katherine MacBride), but I’m sure the code will go through many other versions before it is sent out into the world.

So far our meetings (including the big assembly) have been wonderful for coming up with questions and ideas, and sharing doubts and fears, but less useful for engaging in the actual writing process. Writing is a private, slightly mysterious activity, even when it comes to codes or manifestos. What seems to happen when we try to write as a group is that the tone becomes more tentative. It’s easier to agree on what needs to be scrapped or added as a general concept than on what we should actually write word by word (while we all try at once to figure out what we think and how to share it with others), so the result tends to be bland, non-committal, anemic. Still, I have a lot of trust in and curiosity for this process of writing and rewriting, of comments being added to sentences, of issues being pointed out and collectively addressed.

There are problems, of course. Who are the people who are doing this work, and what allows them to still be involved in this process? Do we accept that the people who are here are the people who are supposed to be here (as per the Occupy principles) or do we recognize the power differentials and the material conditions at play? While there is a little bit of funding available (thanks to the Assembly’s Collective Pot and the contribution of the Arts Collaboratory), it is definitely not enough to support our work. Who can afford to work for free?

We can’t leave this process entirely to chance and opportunity as we try to build coalitions that are essential to our survival.

In order to remedy the chaotic nature of the writing/editing process we have agreed on using a bibliography/list of resources as a tool that would allow us and the readers of the Code to trace the origin of specific positions and statements. For the sake of transparency, we plan to also present a sort of archive of changes and decisions. We also want to start keeping track of the hours spent on this project while operating a time bank as a way to redistribute agency and empower busy people who might need help with other tasks in order to be at the meetings. But it is not crystal clear yet what the decision-making strategy is and how we can keep this process at once open and horizontal, but also politically focused and not completely open-ended.

We are figuring it all out as we go along. The how of this work is as important as the what, as we try to practice a form of prefigurative politics.

Postscript (December 2020)

After a year of bi-monthly general meetings (which were moved online after the pandemic started) and more frequently small groups meeting to focus on specific aspects of the work, the Climate Justice Code has recently entered a phase of dialogue with the institutions that have been selected as test sites.

We had never precisely established how we functioned, which left us with somewhat fuzzy decision-making processes. When I pressed for coming up with clear procedural guidelines I encountered a lot of resistance: some of us saw the group as a disparate group of individuals who had come together to get something done and then quickly disband (not a collective). But then what was the entity that was supposed to hold each other (and the institutions we would work with) accountable? Who was going to have the authority to speak (since by then we were getting invited to lead workshops and teach at art schools) in the name of the Code? I believed that this authority could only come from a transparent, collective mandate, stemming from a true commoning practice, even if our time together was limited in scope and timeframe. Commoning isn’t something that you only do with your close friends and chosen collaborators, in a bubble of love and comfort. If that were the case, the concept would never be able to hold up as a serious alternative to capitalism.

The legitimate desire to keep things fluid and organic sometimes meant that crucial decisions were being made hastily, without proper discussion and without consulting all interested parties; our nominal horizontality was obfuscating the very real differences between us in terms of social power, health and bank account balance; the few opportunities that were remunerated followed a neoliberal logic of rewarding ‘skilled’ and intellectual work while reproductive work was monetarily (if not philosophically) devalued. And we had largely abandoned the collective writing/editing experiment in favor of commissioning texts to experts, something that I felt very conflicted about, since it meant that the bulk of the work that was left to the ‘non-experts’ consisted of proofreading and ‘caring for’ the Code, whether we fully embraced its content or not.

At the end of October I decided to exit the group because I was experiencing burn-out symptoms. I found myself unable to advocate for the changes that I believed were essential without compromising my health. My departure from the Climate Justice Code was as much about me as it was about the group. I recognize that in my current health state, with chronic illnesses and unresolved trauma, I have a low threshold for stress. Meetings and workdays left me exhausted and sad; it would take me days to recover from them. Eventually I realized that I could no longer cope; self-care became my priority. My material conditions had also changed; I could no longer afford to spend so much time and energy working for free.

These problems aren’t limited to the Climate Justice Code group either. In most groups, unless there are explicit correctives in place, those who are most comfortable, most eloquent, most extroverted, end up dictating the pace and direction of the work. Those who can’t or won’t adapt end up leaving the group. I believe we owe it to each other to materially empower each voice to meaningfully contribute and dissent.

Still, I learned a lot from this experience, discovered a passion for researching the theory and practice of collective processes, and I am curious to see what the Code will be able to accomplish.

We Owe Each Other Everything

Casco is organizing their third Assembly for commoning art institutions under the title “We Owe Each Other Everything” that will take a new format online December 11-12, 2020.

Please see Casco’s website for registration and updated information.

Valentina Vella is an interdisciplinary artist, performer, and poet born in Rome, Italy. She holds an MA in English literature from Roma Tre University and an MFA in Interdisciplinary Arts and Media from Columbia College Chicago. She was the recipient of a CAA Fellowship in 2014. She has performed at La Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome, Links Hall and MCA Chicago. In 2014 she made A Ride West, an experimental film that explores the violent American myths of conquest and self-reliance through a Jungian lens. It is based on a journey on horseback through the American landscape that she attempted in 2013. After a few years of extreme precarity and ill health she is trying to be active again. She is currently working on NetherWorld, an often grim and sometimes danceable sound album about the horrors of neoliberalism. Her research as an art organizer revolves around the idea of practicing art as a commons. She lives in Rotterdam, Netherlands.