Infinity Factory: On Isiah Medina’s Inventing the Future (2020)

Steffanie Ling

February 2021

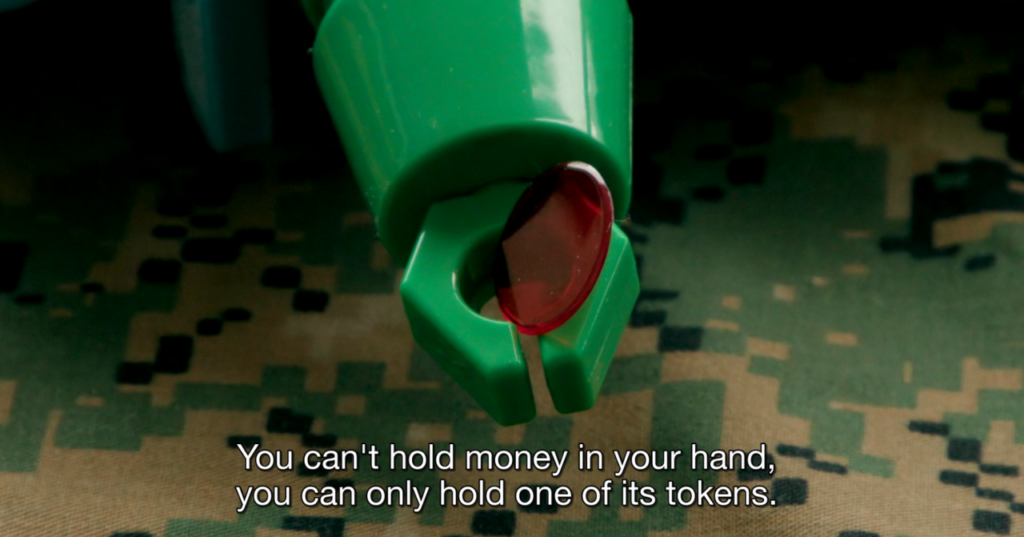

Isiah Medina. Inventing the Future (still), 2020. [source]

Adapting the manifesto into an experimental film also raises questions about aesthetic regimes on the left, especially for time-based media and technology which are intrinsically defined by the historical materiality of the present.2 Questions posed by the text’s political agenda in relation to film can be thought of through a number of dialectical relationships that the film enables. For example, the dialectic of figuration and abstraction speaks to our conceptions of the legible present and the cryptic future. Furthermore, this may correspond to our relationship to tactics and strategies, immediacy and design, leading us to what Medina has described as “decisions” within “structures of decision.”3 It encourages us to ask: What forms are we inclined to accept? What forms do we reject? Why? What forms accept and reject us? Does abstraction condescend? Does figuration democratize? Can there be an aesthetic dimension to praxis?

In Canada, the release of Medina’s film aligned with a brief sampling of the kind of post-work society that Inventing the Future outlines. The Liberal Party suspended student loan debt payments, implemented provisional rent subsidy programs, and issued an initial $81.64 billion through the Canada Emergency Relief Benefit (CERB). In September, this program was bifurcated into two streams of taxable relief, the Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB) for contract workers and a revised Employment Insurance program with broader eligibility for waged employees. In the absence of a revolutionary process, the Canadian state revealed that it already contains syndicated mechanisms embedded within its neoliberal corpus to issue rent subsidies through property management companies, debt forgiveness facilitated through the National Student Loan Service Centre, and later the implementation of a universal basic income model. When the aforementioned influx of benefits intersected with the mass unemployment of non-essential workers, it created a precedent for state-mandated free time. Given this context, and in principle with its socialized means of production (a combination of State arts council grants and crowdfunding), Medina’s film arrived in a sociopolitical landscape already oriented towards the future it describes.

In the text, Srnicek and Williams begin by outlining the contours of folk politics, or “the politics of immediacy.” They state, “Against the abstraction and inhumanity of capitalism, folk politics aims to bring politics down to the ‘human scale’ by emphasising temporal, spatial and conceptual immediacy.”4 Temporal immediacy mobilizes power in reaction to corporations or governments; spatial immediacy refers to configurations that localize struggle, such as temporary autonomous zones and local consumption; and conceptual immediacy takes the forms of projection, spiritual crisis such as moral critiques of the self, consumer relationships, and correcting our apparent proximities to capitalism. “At its heart, folk politics is the guiding intuition that immediacy is always better and often more authentic, with the corollary being a deep suspicion of abstraction and mediation.”5 Examining the character of immediacy anchors folk politics in the scarcity of time. In this sense, folk politics internalizes the neoliberal logic of urgency and personal responsibility as the means to broach systemic conditions and institutional failure.

Srnicek and Williams go on to explain, “Folk politics prefers that actions be taken by participants themselves – in its emphasis on direct action, for example – and sees decision-making as something to be carried out by each individual rather than by any representative.” However, the call to refute the primacy of immediate, palpable expressions of justice demands an enormous amount of self-negation. The social possibility of witnessing and being in a community, the forging of solidarity, and the palpable justice for us and our loved ones that come with folk politics far outweigh the task of establishing radical left institutions. However, although “protests can build connections, encourage hope and remind people of their power,” as Srnicek and Williams insist, “beyond these transient feelings, politics still demands the exercise of that power, lest these affective bonds go to waste.”6

Isiah Medina. Inventing the Future (still), 2020. [source]

This process of structuring decisions is profoundly linked to moments elsewhere in the film, such as when Medina portrays his time with members of leftist think tank Autonomy. Their meeting offers the classically neoliberal long-form planning device (think tanks borne from the elite Mont Pelerin Society cited in Srnicek and Williams’ text) activated as a tool in the process of thinking about the future, consolidating intellectual power towards a left post-work society. This facet of the film offers a progressive strategy that contradicts the notion that neoliberal tactics (e.g. think tanks) intrinsically serve a neoliberal future. Medina also associates immediacy with decision (if it is seen as a unit separate from a continuous structure of decision):

Often this idea of decision is thought in only its immediate form, in face to face situations, making a decision, but the structure of decision making can be very long term, and involve many actors to, in a way, complete the decision, which may in itself be a large collection of yes/no, from different points of tension, institutions, at different scales.8

Abstraction is manifested in decision-making to create new decision-making structures. In the throes of abstraction, neoliberals decided “that which isn’t” and consolidated power to make it “that which is.” The gradual implementation of the aforementioned social policies in Canada since the beginning of the pandemic illuminate an enduring apparatus that already exists to liberate our time but has only been known to configure power and wealth according to neoliberal capitalist hegemony. Medina explains, “I think when we decide on the future, it’s also a risk, a gamble on the future. Rather than a politics that fights for the future as if it’s something that’s far away, a politics that fights in the future anterior is different. It fights as if the world is already here.”9

Inventing the Future [Youtube], 2020.

By offering cinematic form to the intellection of rupturing that cycle, Medina also negates conceptual immediacy by bursting the myth of the partnership between intuition and artistic experimentation. When asked how he employs intuition in his filmmaking, Medina responded:

If this movie is experimental, I would want to do the word “experimental” justice in the fact that to experiment, I would need a theoretical anticipation as well, [for there to be] a movement of thinking outside conditions (each condition introduces its own form of outside to be integrated into cinematic meditation), theoretical writings in and outside one’s head, and attempting it in the edit and shooting, that is, in the proofs. I don’t trust intuition, I think it is intuition that can keep us in these cycles.12

Medina unsettles the dialectics between experimentalism and spontaneity, philosophy and abstraction. Approaching experiments with theories and conditions articulates a strategic orientation that resembles, in the gaps between hypothesis and actuality, science more than art. Working within the medium of time and the material of image-documents, Medina attempts to evidence how post-work futures reside within mechanisms in the present and show what possibilities reside within abstractions generated through experimentation. Images that seem random in the film visually indicate certain demands that Srnicek and Williams call for. One of many examples include a military style jacket featuring a pixelated camouflage pattern. At times, we see this pattern cut back and forth with shots of a green block, or a physical iteration of a pixel. This particular pattern is the Canadian Disruptive Pattern, a computer-generated digital camouflage pattern that was developed to prevent detection by night-vision technology and was selected as a motif to put nature in dialogue with automation, technology, and the military. This specific camouflage pattern harks back to the tension between nature and denaturing, which recapitulates the emancipatory prospects of non-natal gestation, a motif that is represented as a 3D animation of an infant suspended in an incubating space pod elsewhere in the film.

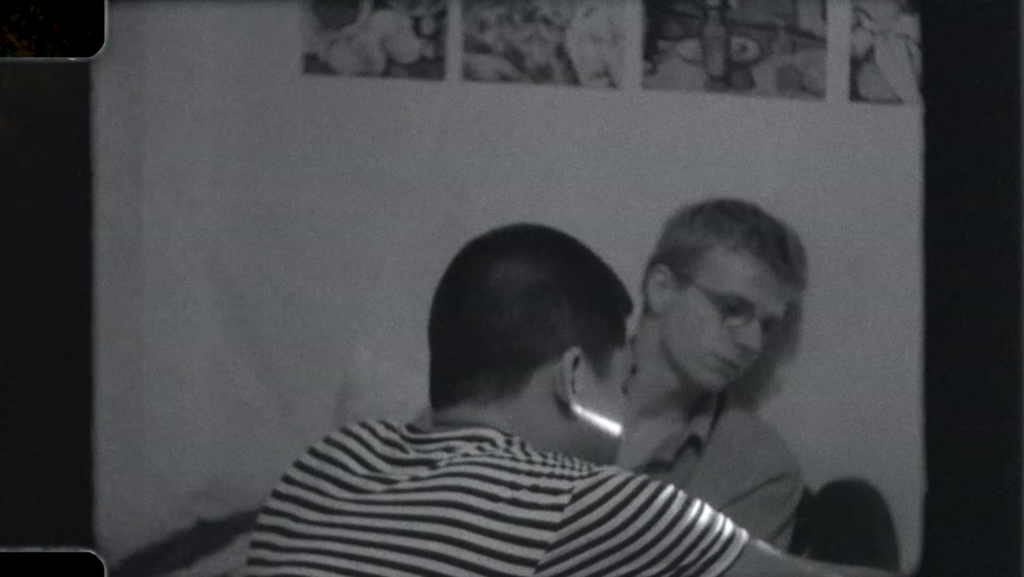

Isiah Medina. 88:88 (still), 2015.

Throughout Medina’s work, philosophy, political practice, and materialism are entwined. Viewed in retrospect, the conditions that prompted a collection of decisions come into fuller focus. His previous film, 88:88 (2015), premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, Locarno, and New York Film Festival – coincidentally, in the same year the book Inventing the Future was published. 88:88 depicts Medina, his comrades, his family, and a crew of young people in a low-income neighborhood in Winnipeg. They navigate the law, friendship, Badiou, and more. They produce their means and their meaning through the time that is captured and offered. The title of the film refers to the numbers that flash in an appliance’s digital clock face when the electricity is cut (88:88, –:–, 88:88, –:–). Like this cursed flashing, Medina’s editing style is frequently compared to Soviet montage, a meditated maelstrom of images quickly appearing and disappearing. For Medina, the cut summons a gap between reality and its image-document. In the editing process, the cut performs the dual action of dividing and suturing documents of reality into a linear time-based experience, a film. The cut divides by placing a gap (so small and of inconceivable depth between these documents) and forms a temporal bond in the time-space of cinema (infinitely close but never touching).

Further, the number eight invokes the mathematical concept of infinity, which can be understood as an anti-number. Where a number is a device that captures and allocates time and capital, infinity enters, making a space for invention. Medina’s thinking around the cut is also indivisible from the inevitability of poetry (that requires neither resources or technology) and even casts doubt on democracy’s role in promoting a vanguard – cinematic, philosophical, political, or otherwise. He states:

Philosophy must present new choices, which is also to say philosophy needs to draw new divisions not given by democracy. Cinema must show new presents not presented by those movies that are voted into our movie houses. I do not think to be able to present the present one needs money, technology, or democracy for that matter. In the same way that poetry may not need a technological change to think a truth [sic] of poetry, or a mathematician at present does not need the resources of CERN, I think that to think the cut [sic] of cinema, the technology is not important since the form of the cut’s appearance is invariant.13

For Medina, the cut rearranges realities by gathering fragments of atomized experience into experiential proximity with many others. This is how cinema manipulates time as it elapses. Film’s rearrangement of reality is always a proposition to remake the sense of those times, those lateral realities. The correlation between the cutting of electricity and the cut of the image, the quad of figure eights and the mathematical considerations of infinity, accomplish a poetic circuitry. Between each cut, infinity is produced in multitudes.

Isiah Medina. 88:88 (still), 2015.

Medina’s frustrations with the limitations on cultural participation and political education under this framework foreshadowed his determination to elude this typical elite circuit for his second feature. “[88:88] deals with questions of philosophy and how we’re going to conduct better ways of living,” he told Point of View Magazine in 2020, “I think people who will want to see the film the most, like the younger generation, I’d really like to have them be able to watch it for free.”14 Medina, who has amassed a broad and youthful fan base by sharing his earlier films free online, has never undermined the intellect of his public. Following the release of 88:88, it was apparent that Medina’s ethos was not compatible with present industry conventions designed to manufacture and uphold a film’s scarcity and to power neoliberal economies of labor; for example, by cultivating competition between freelance writers who pitch to precariously financed (and often niche) press outlets in exchange for exploitative, but broadly accepted, rates of pay. In other words, filmmakers also participate in the successful application of an effectively scaled and planned neoliberal marketplace that presents the ritual of meritocracy. Films are often invited to screen at festivals funded by arts councils, corporate sponsorships, and individual donors for small or non-existent fees with the idea that the film will be selected by a distribution company, receive a theatrical release, and therefore contribute to financing the filmmaker’s next film. In actuality, experimental films such as Medina’s are not aimed at that particular market but are presented in hybrid art and cinema programs that are even more precariously financed niche corners of the larger market. The existence of these programs are increasingly difficult to justify to arts councils and donors, so proof of cultural supremacy is needed. Depending on the scale of the festival, press outlets and critics triangulate arrangements to guarantee coverage for the festival’s program in exchange for the critics’ travel and accommodation to attend and write about the festival. Understanding conditions like these, Medina’s choice to premiere his film for free is driven on an experimental premise:

It was a question of decision, like that classic joke that the Slovene psychoanalytic tradition likes to use from Ninotchka (1939) when someone asks for coffee without cream the waiter says, “We’re out of cream, but I can get you coffee without milk.” Two different negations that aren’t exactly the same in the sense I can get paid nothing and play in a festival – or I get paid nothing, but put it online for free. In both instances I’m not paid, but the results are different.15

Despite forgoing this circuitry, some results are also the same. Medina’s films have been reviewed in the typical cohort of journals, MUBI Notebook,16 Cinema Scope,17 and Hyperallergic.18 While sharing Inventing the Future for free online generated a familiar official discourse, it also widened openings for unofficial discourse, galvanizing a uniquely varied commons that shifted the rhythm and pattern of a typical film’s public reception. Shortly after its YouTube premiere, the film was posted to Canada Left, Basic Income, and BreadTube subreddits. Following a screening organized by a contemporary art museum in St. Petersburg, Russian subtitles became available alongside the free download link. On Letterboxd, a social networking site for cinema enthusiasts, the film received critiques ranging from resigned mystification to charges of graduate-level displays of grandiloquence, overt elitism, and most dramatically, technofascism. The critiques were punctuated by notes of gratitude, revolutionary sentiment, admiration for the film’s cinematic language, and accolations of mastery. Interestingly, an early user remarked that he would revisit his initial appraisal with greater investment, and later published an extensive addendum declaring deepened respects and disagreements.

These examples of immediate and personal discursive activity resembles the type of emboldened commons nurtured by the video game or skincare industry whereby audiences are encouraged and rewarded to rigorously critique the cultural object in question (the product) as soon as it is released – without any further interpolation other than playing the game, hence entering and shaping the game’s economy of culture and capital. However, the difference between fostering criticism around a product and the aggregate criticism expressed in the aftermath of Inventing the Future’s release is the total absence of capital. Denizens of Letterboxd will opine on films for no apparent economic reason. Out of that condition, Medina’s film is met by audiences who parse the film’s legibility of form and deliberate on the utility of its politics from a spectrum of aesthetic and conceptual desires and motivations. In the process, their thinking draws forth their own philosophical renderings in relation to what the film proposes. Their willingness, and resistance, to think beyond the film itself cuts across official and unofficial modes of discourse (including those that are often attributed to promoting products), while the film and the thinking (writing, posting, sharing) resist becoming a product in the process. Now, consider this pattern of desire to think of films and the discussions around them (or in essence, anything you like doing in your free time) as an activity indirectly subsidized by the State – not through emergency funds or stimulus checks, but universal basic income.

Isiah Medina. 88:88 (still), 2015.

In a gesture that conflates mainstream cinema marketing, a ubiquitous technology, and Situationist détournement, Medina recently began promoting his film through a street postering campaign outfitted with a QR-code to offer another means to encounter the film. This distribution strategy, while modest in splash, continues over a year after its release to inventively mingle forms that the circuit both relies upon and occludes. Striving further still to expand the film’s already abundant availability deepens its stunning contradiction as a state-funded, de-commodified art object that prefigures an offramp from the ideological restraints of market driven legitimacy to circulate between art and post-work propaganda. Because it has its own method of circulation, Medina’s film doesn’t pander to the market (of festivals and film journals), yet it is still able to capture the market’s attention and accolades. In other words, engaging with the tools and forms of capitalist production has not compromised it’s radical integrity to the extent that it circulates across a spectrum of discourse without the reproduction of capitalistic value. By including mechanisms we are already familiar with and operating within, the film expands the territory for radical thought and activity.

Inventing the Future (poster campaign), 2020.

Time-based media and the Left share a future-oriented ontology. As long as capital accumulation is systemically tied to the exploitation of labor and time, the struggle to emancipate time is beholden to the progression of time itself (that which compels us forward) with or without a broad left consensus about the validity of thinking in the future-tense. Cinema is a medium invented through experimentation – and hence revolutions – in optical sciences and chemistry that succeeded in imprinting time, fragmenting reality, and producing mass spectatorship. Thereafter, the desire to deconstruct temporal order made evident by this technology gave rise to complex cinematic languages and the desire to experiment. To recapitulate Medina’s clarifications on the experimental, experiments are operations that require “a movement of thinking outside conditions,” that which creates an opening for poetry or art. However, without being rooted in conditions (such as the mechanics of cinema’s technology itself), poetics cease to be experimental – perhaps, it becomes merely intuitive. Experimentation is a movement adjacent to, but which strives to go beyond, a condition. Experimentation is inherently time-consuming. The lack of immediacy practiced in Medina’s mode of inquiry and the structure of his cinematic language provokes a confrontation with the chronic scarcity of time to grapple with the complexities of global capitalism and neoliberal hegemony. Being unable to know our condition effectively hinders our political motivation to move beyond the provisional forms of justice we can manifest through a folk political common sense, a politics of immediacy. Medina’s Inventing the Future operates in the aesthetic regime as an embodied future-tense – the recuperation of time from the duress of work. The filmmaker states:

I think it’s important that the history of movies coincides with workers having more leisure time to attend the cinema, as much as I also think the notion of free time is already embedded in the cut, freeing time from its temporal order of past, present, future, that is given in a shot, like a work schedule.19

For Medina, to self-determine (to read, study, and live as discursive beings) is not a prize to be won after the revolution. Instead, self-determination is intrinsic to the process of liberation from the capitalist temporal order.

Footnotes

- Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work (London: Verso, 2015), e-book.

- An aesthetic regime is a term borrowed from Jacques Ranciere’s critique of Modernism as a totalizing category of art that “seems to have been deliberately invented to prevent a clear understanding of the transformations of art and its relationships with the other spheres of collective experience.” I employ it (liberally) in this text to communicate that aesthetic regimes on the left exist to reestablish the heteronomy of art (influences outside of art), but I maintain that subverting the dogmatism of art does not stand in for political struggle. See: Joseph J. Tanke, “What is the Aesthetic Regime?” in Parrhesia 12 (November 2011): 71-81. [PDF].

- Isiah Medina, email correspondence with author, October 23, 2020.

- Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams in Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work (London: Verso, 2015), e-book.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Isiah Medina, email correspondence with author, October 23, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Left melancholia is a Benjaminian sentiment: “potential insights gleaned from brooding over one’s losses” or “the productive value of ascending sadness and mourning for political and cultural work.” Wendy Brown characterizes it as a “certain narcissism with regard to one’s past political attachments and identity that exceeds any contemporary investment with political mobilization, alliance or transformation.” See: Wendy Brown, “Resisting Left Melancholia,” in Verso Books Blog, accessed December 24, 2020. [link]

- Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, “Left Modernity,” in Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work (London: Verso, 2015), e-book.

- Sarah Salovaara, “‘There Is No Thinking of Poverty Without Subjectivity’: Isiah Medina on 88:88,” in Filmmaker Magazine, accessed October 14, 2020. [link]

- Ibid.

- Vivian Belik, “Review: ‘88:88,’” in Point of View Magazine, accessed October 14, 2020. [link]

- Isiah Medina, email correspondence with author, October 23, 2020.

- James Slaymaker, “Review: Isiah Medina’s “Inventing the Future” Charts the Origins of the 21st Century” in MUBI, accessed February 15, 2021. [link]

- Phil Coldiron, “Movies for Robots: Isiah Medina’s Inventing the Future” in Cinema Scope 84 (Fall 2020): 26-30.

- Justine Smith, “What Does it Mean to Make a “Postcapitalist” Film?” in Hyperallergic, accessed February 15, 2021. [link]

- Isiah Medina, email correspondence with author, October 23, 2020.

Steffanie Ling (b. 1991) is a writer, cultural worker and guest living on the unceded territories of the xwməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish) and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) First Nations.

She is currently researching New Work Poetry, Situationist comic strips, Soviet era animation and organizing study groups on Discord.