Dark Study: Within, Below and Alongside

Nora N. Khan

March 2021

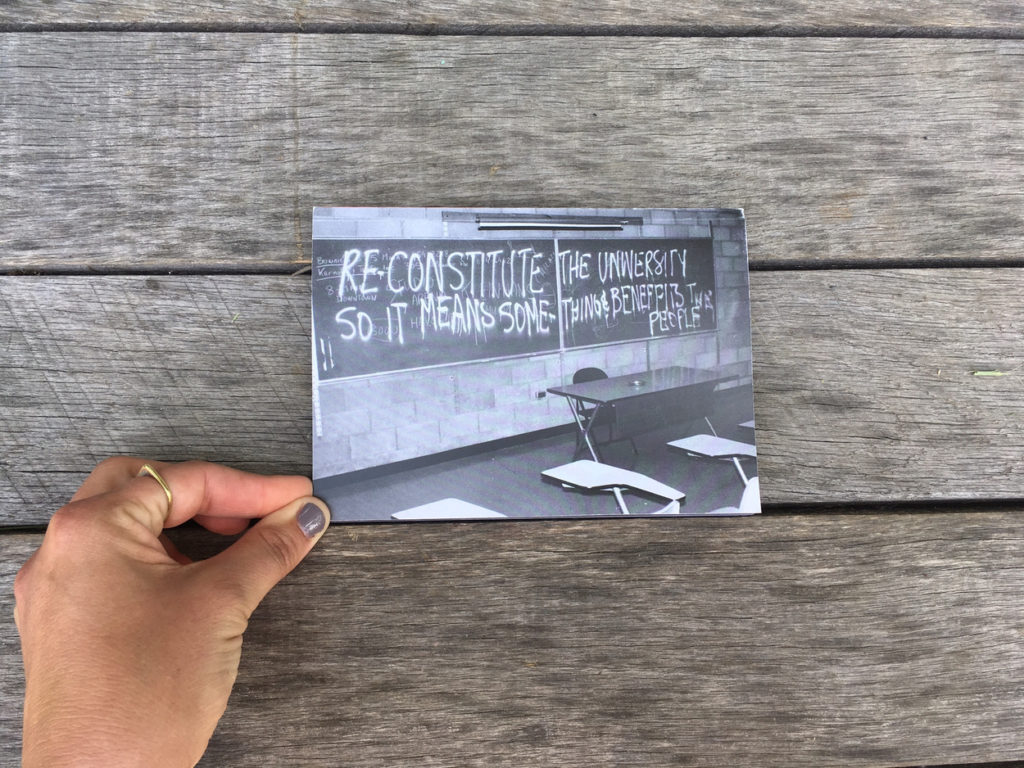

Image from “Studies from the Bottom Up,” a publication and exhibition exploring the contexts of education, curriculum, and communal life emerging from Tolstoy College at the University at Buffalo (1969–1985), curated by Julie Niemi. [source]

How to go on? School was always a way to go on, to find a way out and through. My relationship to schooling, to education, to study, is both one of both hope and sadness still beyond even my ken. I can summarize: it was all-important, life and death, for an immigrant’s daughter to go to school when her parents gave up everything (not just home) to themselves go to school, and then for her to do the same. It may read as overly dramatic, but that’s what it was. To read and absorb everything, not just to learn how to write a paper, but how to think, how to find a way out. School was a stand in for everything good that we didn’t practice with each other. You could teach yourself into a better life. Reach down to those bootstraps and pull, and pull. But performing unimpeachable success wears you down over time. Maybe that striving and competitiveness carries over to a creative practice. Still, one day, the striving stops working, stops being useful. The cost of the meritocracy myth, and of denial, is so high — devastating! You suddenly don’t move. A wall goes up. No key works. There’s no door.

At this point, one finds just how much the schooling didn’t really teach one to survive as an artist or writer, or as a person. No matter how hard you worked as a woman, for instance, someone would always say you don’t know what you know. On Twitter, I sometimes read accounts of women computer scientists who are essential to the design of artificial intelligence. They list all the times men questioned their expertise, at each point of their career. Is there a course in school (not just feminist theory) that teaches you, yes, you can master this very course material, even become a pathbreaker, but someone will, like clockwork, tell you that you don’t know what you do know? Is there a lesson plan on what to do when you are gaslit into thinking you don’t know what you have assiduously learned? A module on how to go on from there? Women know how misogyny infects beautiful “pure” spaces of learning. Students of color know how knowledge is gatekept, what the “preferences” for a specific style of conceptual work really means. We know how our delight, our joy, our play, is sidetracked, taken off-road, by these delightful games of proving ourselves, by a brutal evaluative system that pins our worth to our continuous output in one register, one tone.

Even as one excels in school, the mess of one’s life and history tends to roll and crash through the nice, clean picture. Even as doing well in school kept us from a life of squalor without access, I creep along years later, picking through clues in the ruins of my mind for what was lost. One thing my family could not account for was just how trauma builds up over time in the body. So, looking at the wreckage, I think, it’s some miracle to get out with words and some of one’s mind intact. And when I do find the words, my voice continues on not for me, but for those behind. What I mean is, I know in my bones how many people go to school and universities to escape familial expectations and forge their own way; for how many art school, especially, is a massive personal risk, and how many might never say a word of any of this in a class. The classroom, a simulation of some kind of start over.

Gone Dark

Maybe we are naive to believe in art as a force for personal transformation. I know how both art and writing, and co-learning with many across continents, has saved my life. This struggle together, towards intellectual practice, is as close to a sacred pursuit as I have. I get overwhelmed with a sense of futility, and then think about an idea, stretching from my house to others. I edit, write and think with people in Indonesia, in South Africa, in Cambodia. Their reception teaches me.

I dig back down into the dirt of where I started. I find a poem I wrote in high school, where I describe the weeping I hear in the house in veiled terms, the unbearable catastrophe of a caretaker’s life of fear, disaster, and abuse. I study through their weeping, through their mania tapering off, through depression rising up to take them again. Survival mode. How I managed to study while dissociating in a small two-bedroom apartment where our lives were falling apart, I don’t know. The unspeakable comes to mind: the sacrifices one’s poor family makes for access to the “good schools” — were they worth it? I just tried to do well, do my best, do the best, through impossible turmoil. That was my identity. Writing poems and drawing and building worlds kept me moving forward, and that’s all the role art played: a way to survive mentally.

By re-evaluating my personal narrative of being a creative, my experience of the art world and writing, I can better re-examine my philosophy of teaching criticism. As creatives without a legacy, or a house, or security, without a safety net past one another, without too much emotional or psychological support, we map how we moved through it all, accruing other kinds of tender learning. The clues to how one reaches study are in our own vulnerable stories.

Maybe I think of these choices more now, as without health insurance our adjunct colleagues are asked to please, come onto campus, to maybe get sick and get others sick, for universities that don’t care whether we live or die. What are we learning and what are we teaching, in signing on to this situation? What are the outsides we end up inhabiting, anyways, even when inside? At what point do we say, enough? How do you evaluate the unspeakable long-term cost of working in a place that you are against and is against you? Maybe we are too afraid to own how our life’s work, our intellect, has been dispossessed, even as it still resists capture. It needs no paper or walls to validate its effects; it is always with us below, within, alongside.

The art school’s offering is still exclusion; its gates, its police, its lawns on which we can cavort while, a few blocks away, the poor are stopped and frisked. Fear injected into their communities so we can exercise our radical imagination. The university classroom is rife with expectations, before you step inside of it. (The application ensured the prospective student produces themselves legibly.)There’s a feeling of being trapped inside much as in a museum.1 Grids, high white walls, atomized stressed striving. Students bring in cots to sleep on overnight. The studio floor sets up a system. Theory syllabi ensure one’s knowledge sits in reference to the right people and the right ideas. If you haven’t had access or read the right people, you know, on some level, that your language in these spaces will be off-color (wrong). A school will change you, and it teaches you as much about how people will interpret you, misunderstand and dismiss you, as it will teach you about a creative life.

Dark Study

Dark Study is an experimental program centered on art founded by Caitlin Cherry, and directed by Cherry, Nicole Maloof and myself. The proposition of dark study, study gone dark, is simple. Higher education should be offered online in full, to truly protect health. It could and should be free. An adjunct, relatively un-surveilled, cuts out the middleman. She offers the same class with the same texts. She asks students to represent themselves as they desire, as their game handles, their avatars, or second or third selves. She teaches by making space, allowing online to be a place where each can attempt to embrace criticality and critique against those spaces that have failed us. Forms of dark study cut ties to debt and university regulation by being free; forms of dark study allow one to operate within, below, and alongside. In plain view. Our proposition is that cutting ties of an art education to debt takes impossible pressures off the learning process and frees it to breathe.

There are core canon problems — a veneration of genius and mastery, the use of criticality as a shield, a stress on the stakes of one’s work, a disciplinary relationship to authorship and ownership. These demands shape the story one writes. Demanding a language of legibility shapes the work. Critical terms of evaluation, critique, shape the work. They cut or expand the artist’s sense of possibility.

As teachers, we need to create our own storytelling, that’s true. And for that, we tell each other stories of how we learned to move according to an interior visionary compass that we had to invent for ourselves. We take these stories into a room where our full dimensionality is allowed for. I login to say, speak on your past in code. Play with others’ expectations of you. Think with others — on Slack forums, in chatrooms — to make an ethics of collective thinking. Recreate one’s citational practices. Embed what you really mean, with a smile. Find your internal motivation, beyond accolades and prestige. Would you do this work alone if no one was watching? You may have to; you might want to.

Through the last months, we’ve slowed down and zoomed out, researching the legacy of famous experimental schools, from Deep Springs and Black Mountain College to Tolstoy College. For years, I’ve heard about anarchist syllabi embedded in the middle of state schools and wild collectives that took place off-grid. In reverent tones I heard this was where the ‘real work’ happened. The romance of Deep Springs dominated graduate school, how the poets farmed and learned service and the value of labor, autonomy and self-governance. Friends who live in Asheville, North Carolina, tell me about growing up in the shadow of Black Mountain. They’re themselves taciturn, experimental, deadly serious. However, even the most loved experimental schools, where radical practices and righteous values are elevated, can fall prey to a lack of self-reflection. Charismatic men and women dominate in the vacuum. The same old dynamics; women and black and brown artists and organizers describe how their work and intellectual energy is lifted and rebranded. While principles of freedom and access in communal experiments can be seductive we might ask, freedom from what, exactly? How to ensure age-old inequities don’t creep into the labor-cum-art practice?

We have focused most recently on the work of KUNCI Study Forum & Collective, a pedagogical and communal “thought experiment” based in Indonesia. Through their School of Improper Education, they aim to “horizontalize knowledge circulation, not only by collapsing the rigged teacher-student relationship, but also demystifying the role of the book as a sacred container of knowledge, towards operationalizing different modes of being together.”2 KUNCI’s founders ask, “How does a school operate while questioning its own reasons to exist?” Extending this question, we ask, how do we operate as an art program that questions its own grounds, its legitimacy, its claims at each step? Could a dark study abandon the MFA gospel of a definitive set of paths towards fully-developed artistic research? Could a dark study hold space for undoing modes of hierarchy and control that bleed through it? Can dark study help undo our preferences for what kind of thinking is allowed, tacitly or through force, in higher education? What models do we never allow in?

In “the university: last words,” Stefano Harney and Fred Moten speak of the critical intellectual, how they labor on, in isolation, faced with an impossible question, namely, “How much of the academy’s libidinal political economy is predicated on the fantasy of a livable (individual) intellectual life?”3 You will not often hear in an MFA that an intellectual life will most likely be unlivable in our economic system.4 To speak on the difficulty seems obscene, against the grain of a neoliberal gospel; if you want it, you’ll get it. That’s the end point of the story of mastery, discipline, monastic training — there’s no allowance for the other ways a life as an artist, as a thinker, as a writer, as a person without many resources, might look. “My” “work” is forever captured and distributed, given and taken away. Though “the university regulates certain kinds of theoretical and empirical, intellectual and sensual study,” as Moten and Harney add, one can also count on the university not noticing sensual, theoretical study at all.5

Unlearning

Every effort to unlearn becomes a rabbit hole. A little digging shows the lessons of mastery, control, ownership, pervades all our creative work. My own MFA model was of men fighting each other in internecine turf wars. Mastery was everything. Before, it was weaponized in the colonial classrooms, the punishment, the military discipline, the crushing exams, the triumph through them. I watch this reverence for discipline and fear show up in my life, from one grandfather being a feared headmaster of a high school, to another grandfather tending to remote peoples in the Chittagong Hill tracts as a doctor. There are many echoes and parallels; their British colonial classrooms evolved into many of the classrooms of today. Internalized narratives of improvement of desperate life possibilities began decades before I was born. I gather their stories of learning to learn how I learned to know.

Collective thinking means we would, as teachers, let go of ego, of certainty, of holding the sole answer. Questioning what we name as civilization allows for wildly different approaches to history, from outside the perspective of the state. We barely know what we don’t know. We might catch each time we tend to dismiss and devalue amateur knowledge and labor produced outside schools. What are narratives of learning that do not stress improvement, self-betterment, an imperative to be a better worker, cultural producer, citizen? The production of the state is a narrative mode, in which we move from stateless to in-state, unlearned to learned, uneducated to educated.

I want to disappear as “a scholar,” “a writer,” “a thinker,” a “professor.” I want to divest myself of these terms of naming. I write through disappearances and dissolution. Remembering the outside, I could better attune to the classroom’s shifting dynamics, its unequal labor, its factions, its orientation. I can bring the ongoing, violent history around and deep in the school’s foundations to the surface. As we all, teachers, essay to find new modes of being together, virtually, we must destabilize the “rigged” setup of teaching. These spaces are communal, but how, and for who? How is difference negotiated within that communal space? How do we break down the programmed ethics of ruthless individualism that make the communal impossible?

A classroom itself should have an active theory of change. The instructor works to actively destroy an archaic relationship with students. They move with the times. They let their experiences and life outside help them question their role inside.

One of our first steps in Dark Study is blinding all institutions in our application form. But the institution will still come through. Its ways of speaking, writing and processing, its networks, taught social gestures, signals and cues. I wonder how we can mask our memories of training and unlearn preferring a rhythmic sentence, or ignore expression that is intentional, deeply-researched. To commit to unlearning our preferences and tastes means we have to be able see what they’re rooted in, defend them to one another and hold each other accountable.

Mastery

We test out the various ways our experiences grew a respect for control, humiliation and domination. We also work to unlearn the demand to demonstrate mastery or perfection in order to have the right to speak.

In study with my collaborators (Caitlin and Nicole), we have circled around what mastery means for artists and writers in MFA programs, and how concepts of mastery are passed down through pedagogy. In writing, mastery has a sure allure. We learn to write as much as we learn the story of the master, well, mastering their craft, toiling through hundreds of thousands of words. Seeking mastery seemed to be the purpose of the practice. To try to be the best at what you’re doing, whatever it may be, striving, failing, trying again — these were considered virtues. You had to make mind-boggling sacrifices to be great. We count the master’s struggles. We imagine an elusive horizon where one’s prose would be so unquestionably good. Their command of language would transport and shake. The pursuit of mastery really taught, at the least, discipline, showing up daily, messing up, writing through all the discouragement. Longevity was untaught.

Even to become a master, or an authority, an expert would not protect you from being continually degraded and told you know nothing. Some of us know what it is to be simultaneously elevated, then trashed. I read about Woolf and Rhys and Morrison and Wynter, Butler and Lorde, how they encouraged themselves through obstacles, how they pushed themselves to go on. “So be it; see to it.”6

Alongside

Young women want to know: how will I keep making work? Young Black students and students of color want to know: how will I do this painting/sculpture/glassmaking/writing thing, without any models? We share something, I realize, across a decade: critiques by male professors and peers which end in shame and tears; passive-aggression and gaslighting and infantilization; white men using feminist theory and postcolonial theory to harass and denigrate women of color. The bad stories evolve each season. How can I tell students that the world after graduate school will hold variations on this kind of experience? How to continue on? How to block, deflect, reflect and compartmentalize so your spirit will not be worn down? What is the life of your art after dropping out, or being pushed out, or finding yourself unable to return, the costs too prohibitive?

We start to hang out and gather to make sure we aren’t losing it. We encourage each other; we spend time discussing what happens in the walls. We linger in a field alongside, pacing, running our hands along the walls, thinking about who we’d be if we were totally taken in by the university, embraced, elevated in it, or if the work in there is really needed for the work out here. A space alongside where students faced with making work in a precarious economy at enormous personal cost can zoom out to see the stakes of their art practice.

Alongside, the vision of a solitary genius honing their craft alone seems untenable. The artist’s life, a fantasy embedded in intellectual separation. We move alongside these inner rooms, because alongside is where our criticism helps turn us spiritually against the institution. Art students seek a bigger context and framework for their work than the art world.

When we first read The Undercommons and dug through more of Fred Moten’s poems, lectures, and theory, we had “study” to describe this work alongside. We were able to give language to what we had been doing all along. Study was the way we negotiated among all our different embodied positions, how we examine how we know. The long conversations we have outside class, the hours put in to thinking through what happened during that crit…

Study goes on within, below, alongside, in light and dark, because we recognize the students, not our students, the artists, must recoup their investment, must get the paper and the key to protect them from the floor falling out from under them. When Zooms open, faces are lined with worry or depression, onto a hectic scene of folks walking in and out of frame. Cameras shut off. I get earnest DMs explaining and apologizing.

The online classroom is an emergent system, its complexity made through dynamics, positions and preferences, affective registers — aggression, digression, despair, confusion, thinking out loud, disgust, joy, wonder — all showing themselves in frame. I stay open to outcomes I can’t predict. I can’t overly design the space. I refuse its language of capture, in key ways. I refuse to check in or check up on when surveillance is intrinsic to online conferencing, or to overly track through the infrastructure of e-mail, pinging, chats. Students already experience a surfeit of university and administrative surveillance. This classroom can be the place that does not happen. We agree that we don’t surveil each other. We agree to give each other space to breathe.

Now, coming full circle into these virtual rooms, there’s an opportunity to study differently. We could pretend like this is the way it’s always been, that we’ve always been in these rooms, and we could claim we’re the first of our kind in these spaces. We could perpetuate the myth of being frontiers people. Or, what if we begin with the real stories of each person in the room? What if we abolished any notion of neutrality and refuse any claim to apolitical purity, of education being a separate concern from how we live now? We might speak on the friction and static of the space, its inequities, before we even begin. We might refuse to keep telling the story of single masters and visionaries winning history, magic heroes. We might take up, instead, the potential of unlearning and undo the desire to level others as we were leveled.

The long game; the long view. Maybe the school goes on for a decade, for twenty years, and you never graduate. Art school, as a space we talk about art, yes, but also commune together, discuss the present, our solidarities. Class is where we create a shared politics that refuses conditions of our own degradation.

This essay was first published in MARCH 01.

Footnotes

- I think here of theorist and scholar Fred Turner’s writing on the history of Bay Area communes, and why many failed because of the fantasy of restarting in the wild from zero, as though being reborn. But whether a classroom or an encampment, a residency or festival, there is no blank slate for sociality, no restart where all our politics, histories, and pain, echoing down through the generations, won’t inevitably fill a “neutral” space.

- In 2017, Ferdiansyah Thajib of KUNCI wrote “Lessons in Impropriety,” a reflection on the first year of the School of Improper Education.

- On July 9, 2020, Fred Moten and Stefano Harney discussed their text, ‘the university: last words,’ as part of the FUC series of ‘rent-burdened graduate students at the University of California.’ Talk is found at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zqWMejD_XU8, and the text was circulated by FUC, and can be read hosted by Paul Soulellis here: https://www.are.na/block/7951400.

- I will credit Workshop Director Lan Samantha Chang for saying, on our opening day of graduate school, confidently, that “90% of you will not write after you graduate.” I took it as a challenge, but on reflection this may have been more commentary on the dedication and grit it takes to write, not an analysis of the financial improbability of such a life.

- Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, ‘the university, last words,’ hosted by Paul Soulellis at: https://www.are.na/block/7951400.

- Octavia Butler, in her notebooks, frequently practiced ‘self-talk,’ which I recognize as a kind of writing many women writers and writers of color practice, to encourage themselves despite all odds and nay-saying.

Nora N. Khan is a writer of criticism. She is on the faculty of Rhode Island School of Design, Digital + Media, teaching critical theory, artistic research, writing for artists and designers, and technological criticism. She has two short books: Seeing, Naming, Knowing (The Brooklyn Rail, 2019), on machine vision, and with Steven Warwick, Fear Indexing the X-Files (Primary Information, 2017), on fan forums and conspiracy theories online. Forthcoming this year is The Artificial and the Real, through Art Metropole. She is currently an editor of The Force of Art (Valiz) along with Carin Kuoni, Serubiri Moses,and Jordi Baltà Portolés, and is a longtime editor at Rhizome. As The Shed’s first guest curator, she organized the exhibition Manual Override, featuring Sondra Perry, Simon Fujiwara, Morehshin Allahyari, Lynn Hershman Leeson, and Martine Syms. Her research and writing practice extends to a large range of artistic collaborations, which include librettos, performances, and exhibition essays, scripts, and a tiny house.