A Year Without (a Third Place)

Kalaija Mallery

March 2021

The feeling of being ‘apart together’ is an exceptional situation, of sharing something important or mutually withdrawing from the rest of the world and rejecting the usual norms, retaining its magic beyond the duration of the individual game.1

– Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place

We all have this year in common.

In my world, I moved to a new city two thousand miles away from home to start an arts administration position just eight days before the city went into lockdown. Right away, arts and culture organizations around the country clambered to postpone exhibition plans and redistribute grant funding towards emergency relief efforts. My position at work shifted and, as a newcomer, I became engrossed in helping others in the community. I learned people’s names and artworks through emails and grant applications; yet their faces, their voices, the way they feel when they walk into a room, remained undescribed.

Without the openness of free and porous social spaces, in many ways I remain a stranger in this city a year later. I have met a few people through masked encounters on the street or at work. I have made friends and started dating here and there, but ultimately I find it is hard to truly know myself under social isolation. Without the presence of a social playground, without its layers and hierarchies of intimacy and connection, the space between me and the rest of the world has become a relational fog.

A “third place” is a term, first coined by sociologist Ray Oldenburg in 1989, for a space between home and work where people come together to relax, hang out, talk and laugh.2 It is often a cafe, bar, bookstore, barbershop, or nail salon where collective commerce meets social capital. My practice was already invested in asserting third places as liberatory hubs in the American social fabric, but a year without one, in a city where I knew nothing except for my work life, presented a case for deeper examination.

We are facing a public health crisis on so many levels, we have lost a sense of a social space, where we come together. In some ways, we are much closer to friends and family now, but on the other hand, there are all these people that you aren’t running into, aren’t seeing on the street, the so-called “weak ties” that you encounter every day that often help in our lives. We may have all these social platforms, places where we might be having different conversations, but what is the constant? What is the community that comes together around them? What are boundaries? What are the rules?3

Third places are usually nestled in a neighborhood where residents of a local community can gather, creating a network of support and belonging. They often serve as a “leveling place”, a place that is inclusive by nature, for folks living in proximity to lend each other a helping hand.4 After a year during which countless small businesses have either been unable to accommodate in-person gatherings or have fully closed, where are these spaces now? And while many have tried to replicate a third place online, is virtuality a fair substitute? In a 2007 talk at Florida State University, Oldenburg suggested that it would never be possible for a third place to exist through virtual communication.5 Yet, much has changed in the years since his initial work. While my pre-pandemic suspicion was also doubtful, the growth of online social networks and our increased reliance on them made it feel almost natural to try to replicate third places online when we could no longer gather in-person.

My exploration into these questions was developed through two online events starting with “a stone’s throw” conversation I mediated this past January with The Southland Institute. Starting with Oldenburg, we unpacked the characteristics, nature, and defining qualities of the third place and reviewed several expansive approaches. We challenged some aspects of Oldenburg’s largely Marxist perspective and embraced other points of third places as spaces for independent laborers and union workers, as well as harbingers for alternative and localized economies.

So much of how it was to be in a non-pandemic place

Was to be seen, like to be on parade

To be seen, to participate

Even if I wasn’t talking to people

An important part of a third place to me is to be seen, to be noticed, a body language that sort of happens6

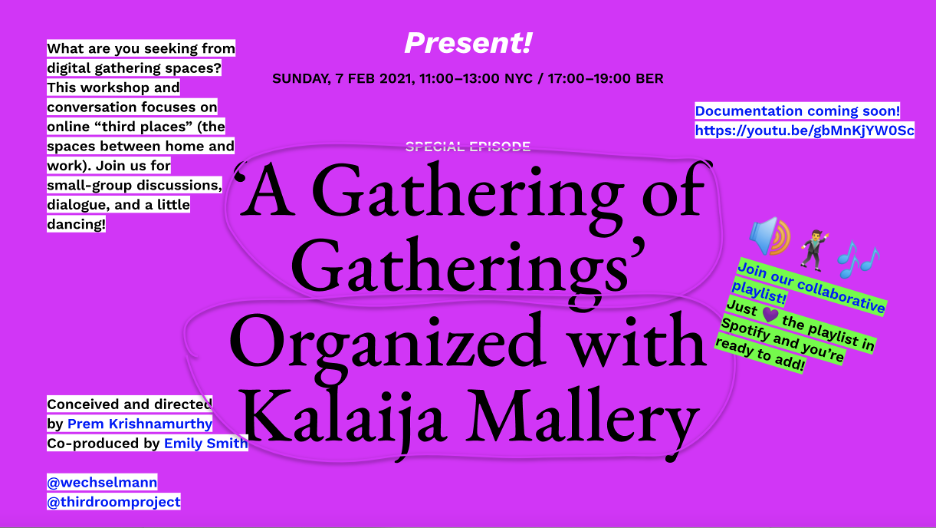

In February, I had the opportunity to continue this dialogue with Present!, a collaborative online series for sharing art and ideas during the pandemic founded and directed by Prem Krishnamurthy and co-produced by Emily Smith. Titled “A Gathering of Gatherings,” this conversation surrounded the ways in which the desire for a third place and personal interactions continues in the aura of one another. What struck me is how the grief we almost always arrived at in these conversations is coupled with the hope that we would someday be together again. We know that the internet will never replace being with others in the flesh.7 Yet, this stasis between joy and grief has become the lifeblood of the third place online.

In his book, Oldenburg depicts a third place with eight defining characteristics:

- A third place is a neutral ground.

- A third place is a leveler.

- Conversation (and laughter!) is the main activity.

- A third place is accessible and accommodating.

- A third place has regulars.

- A third place keeps a low profile.

- The mood is playful.

- A third place is a home away from home.

While there are holes in Oldenburg’s perspective, the general consensus during my discussions was that most can relate to a place that fits most if not all of the previously mentioned criteria. Oldenburg describes the third place as neutral ground, a place that is inclusive and accessible to the general public that does not set formal criteria of membership and exclusion. While there is certainly the possibility of this kind of leveling in most public places for some people, a third place is formed naturally by those who inhabit them. In sum: Everyone has a third place, yet each third place will not be for everyone.

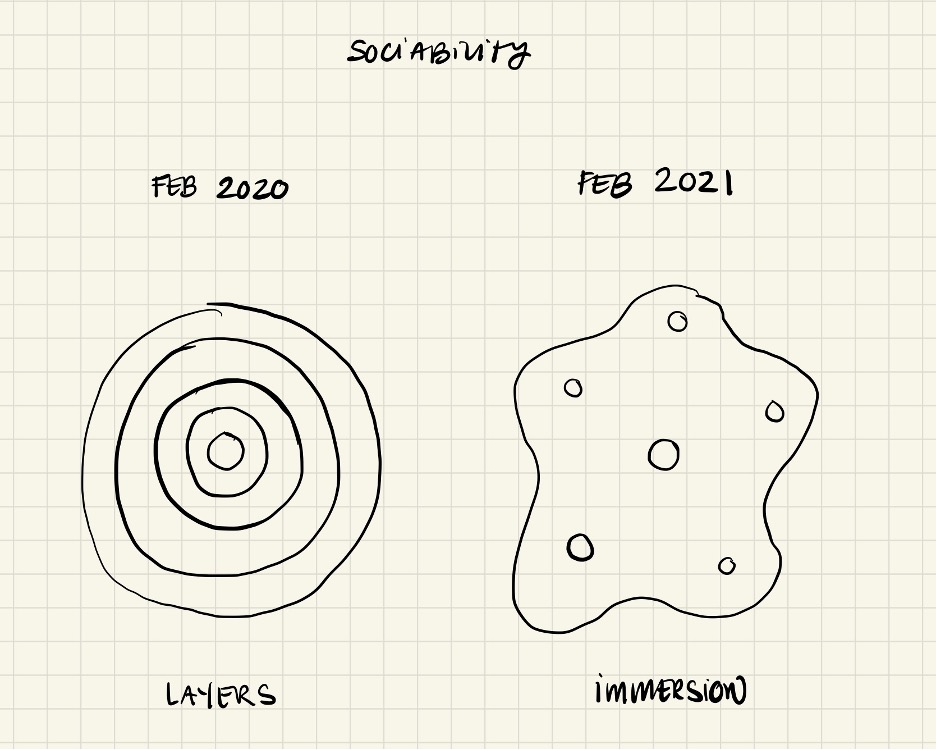

Many of Oldenburg’s characteristics can be replicated in virtual space through careful adaptation of some guidelines. One can hold “open hours” for longer durations that allow folks to come and go as they please. One can create online spaces where laughter and conversation are the main activities. There are even regulars that now cross paths between Zoom events in various circles, especially in fields where folks have had to adapt their work and social lives to life online. New layers of intimacy are maintained and developed depending on what platform one chooses to interact on and every platform has its own vibe, its own function for different people and different moods. In this, a marked shift has occurred. Our layers of relation have collapsed and sprawled. We now orbit each other in various pixels and networks.

-

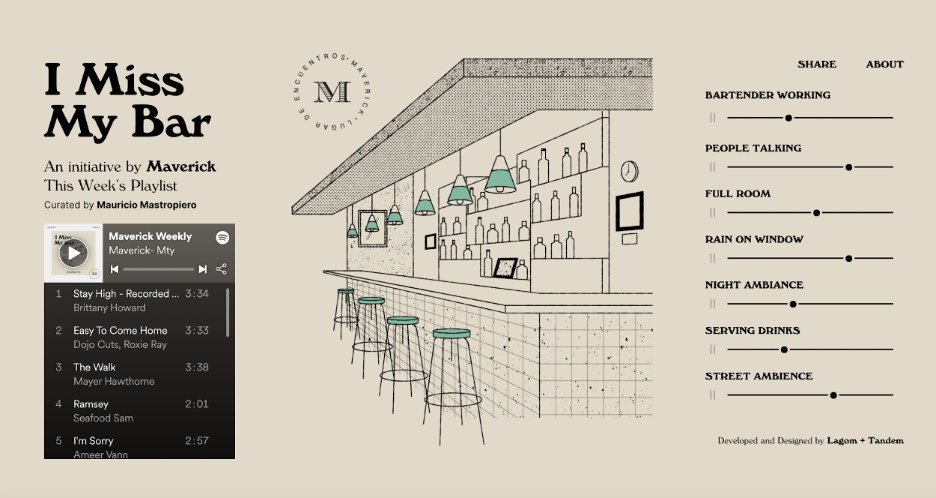

Imissmybar.com was created by Lagon + Tandem as a way to recreate the ambience of joining together.

Most of our third places were bars. While screens may allow us to consume alcohol “together,” in reality you are still drinking at home by yourself. In one of my interviews, someone mentioned that the sounds of third places were what they missed the most. This wasn’t surprising for those fellow artists, writers, and other freelancers who used to frequent cafés and bars alone to work amidst the noise of other people. We took the sounds of other people for granted, and we miss them now that they’re gone. There are apps like I Miss My Bar that allow people to recreate their ideal bar ambience, including details like the sound of shakers and conversations in the distance. To be an extra in someone else’s story holds new appeal.

The loss of bars and cafés also means the loss of physical space for organizing. We miss the accountability of coordinated work and in-person comradery. With all of the compounding disasters there was a need to bring that space to Zoom right away and this past year’s protests have proven that people are using social media to gather, coordinate and organize like never before. However, these online platforms’ architectures restrict certain voices and tensions are rising in the distance between what the algorithms create on our screens and what is happening in the streets. At the same time, with the internet being global in scale, there is the potential for organizing international solidarity against transnational corporations and other planetary scale problems such as climate change. This organizing hasn’t stopped, but it is missing the physical element and the personal accountability that used to be found in third places.

Some participants reminisced about art studios as their third places. One person said that working in a group ceramic studio was their primary mode for artistic communication before the pandemic and the place they missed the most. We know these spaces are not entirely “neutral,” as they require some level of sign-up, capital resources, and other forms of gatekeeping (depending on who runs it), but there are art-centered spaces and studios that are relatively accessible on a broader scope (even if they serve a more specific community) and these are the ones we miss most. Studios seem to be most akin to third places in the arts because of their atmosphere, but the boundaries of work and labor complicate its role as a true third place.

Participants from countries outside the United States shared their range of experiences with the third place from an entire town in Guatemala to Berlin’s open-air markets and Austria’s park benches. There appeared to be a consensus that in smaller cities, neighborhoods and boroughs, it is easier to find localized places, whereas in large cities, like London and New York, the third place may not exist in a static location.

A few people shared with me that they didn’t have many spaces in their life before the pandemic where they freely interacted with strangers. Freely mixing with people you didn’t already know happens best under certain circumstances and dictates whether or not you go back. As Oldenburg aptly put it, “Every regular was once a newcomer, and the acceptance of newcomers is essential to the sustained vitality of the third place. Acceptance into the circle is not difficult, but it is not automatic either.”8 Because art is so localized, it was and remains a challenge for these places to be open to newcomers in that way. Still, these spaces can be critical bridges for artists and thinkers to mingle even among themselves.

-

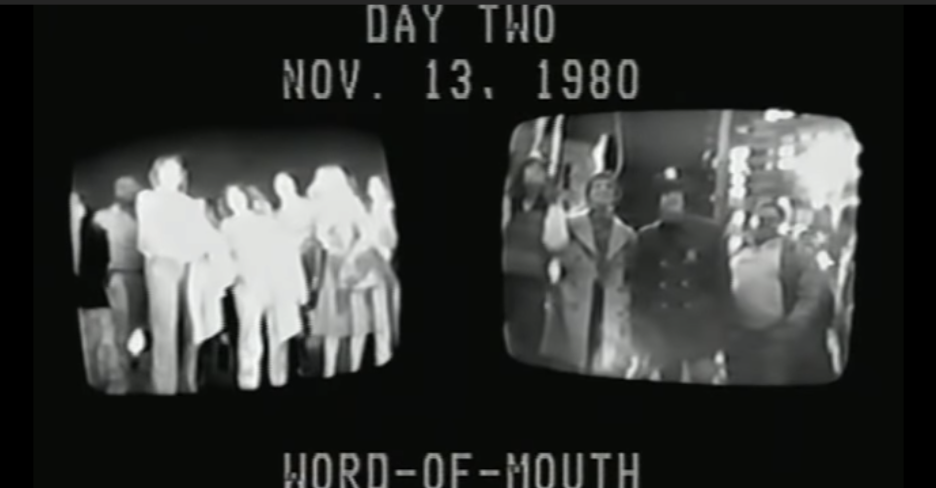

Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz. “A Hole In Space LA-NY 1980.” “The mother of all video chats,” this project was a Public Communication Sculpture that took place in Los Angeles and New York over the span of three days.

To my surprise, folks reported finding what they felt were virtual third places online during the last year. Events were hosted on Instagram, Google Live, Excel forms, Google Docs, Discord channels, the new Clubhouse app, open-room Zoom fairs and online expos where convening occurred in real time and virtual space. These places facilitated varying degrees of interaction and participation, depending on the event, platform, and participants. Each space had its own architecture and reason for existing. The reports of laughter, resilience, and joy from these places were contingent on one thing: the intention of the group.

According to Oldenburg, the architecture of physical third places is unassuming; they have a maximum capacity of maybe fifty people. The intuitive scale of third places allows for a level of intimacy to be reached within them. Digital third places should not assume that those kinds of openings are defaults of their respective platforms. We agreed that the virtual third place relies more heavily on its frame or rules; the structure, moderation, and accountability of the group keeps things flowing. Many of the platforms are free, but come with their own designs; a feeling of “being boxed in” was common among participants. These online spaces needed to have a humble vibe.

With regards to Zoom, the digital third place that had probably the most engagement, folks compared the mechanics of listening and participating while watching a talk to those of engaging in freeform conversation. It appears that, like physical places, how you enter a digital third place and decide to engage is foundational to your feelings toward the space. Do you join with your camera off, or on with a silly background? Do you put your living space on display? Do you keep yourself muted, or do you keep your mic on so that the others may hear the background noise of your life? There has been some disagreement in my findings about the chat function and whether it is helpful to echo the third place chaos of multiple conversations happening at once, or distracting and further alienating to those who are not used to using the architecture in that way.

The architectures of Zoom and other online platforms present a challenge for achieving true third places online, but there are tips for making it as porous and free-flowing as possible: set multiple breakout rooms, make everyone a co-host so participants can move freely between breakout rooms, don’t set a hierarchy of discussion topics and speakers. We agreed that asking all participants to keep their mics and cameras on the whole time encourages a freer flow of conversation.

In online third places there is always a need for someone, a proverbial barkeep, to be holding the space. In reports of successful and unsuccessful attempts at comfortable virtual gatherings, the common determining factor every time was the back-end organization and whether there was a conductor that helped facilitate the common purpose for joining. It seems basic, but in many ways this is the biggest notable difference between online and offline third places. In many ways the “barkeep” is now at the front of the event and given more acknowledgement for their labor.

The reason for being there and the structure of events are what make a third place. If there is too much of a focus on one object or person, the place risks becoming too centralized and may not be as effective at creating the playful atmosphere required for a third place by Oldenburg’s definition. In virtual and physical third places, conversation is the main activity, but there is also beer, music, and games; conversation plus something else. Effective virtual gatherings need intention in order to be meaningful.

-

Sociability and intimacy (2020, 2021). Courtesy of the author.

The public online communications we have found through the art and art-adjacent worlds have been necessary for our emotional and social survival during this time. Many people have reported feeling better after virtual gatherings, especially those that end in joy, laughter, and even dancing. We have learned so much from one another in these spaces and now have access to events and groups all over the world. Chance encounters with new people across time zones certainly didn’t happen in physical third places. Some of us have friends we have never met in person but continue to see regularly online.

We have inarguably gained a greater sense of access to spaces for gathering in the last year, although we still miss our local third places. Everyone I spoke to said they would prefer to be together in-person. Perhaps locality is and will remain a luxury, under the precarious economy and housing crisis we now face. We know that because of capitalism, a truly open third place was already challenging. Within the aesthetic and de-aestheticized stasis of a place that is unpretentious, that it is welcoming to the broadest spectrum of the public, it’s the socializing itself that brings joy to the room.

Prem Krishnamurthy ends almost every Zoom event with dancing, music, or karaoke. I love his use of collaborative playlists as a virtual jukebox in between moments of dialogue. In the spirit of the third place, I have made this playlist for you:

Footnotes

- Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community (Vadnais Heights: Paragon House, 1989), 38.

- Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community (Vadnais Heights: Paragon House, 1989).

- Prem Krishnamurthy’s introduction to “A Gathering of Gatherings,” Present!, February 7, 2021.

- Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community (Vadnais Heights: Paragon House, 1989), 23.

- Ray Oldenburg, Author of The Great Good Place. YouTube. YouTube, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hd1_jNIn-qw.

- Notes from a stone’s throw discussion on a year without the third place.

- By “we” here, I am referring to the participants in these groups. There were all in all about sixty participants between both groups, and they ranged across a spectrum of ages, genders, ethnicities and nationalities.

- Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community (Vadnais Heights: Paragon House, 1989), 35.

Kalaija Mallery is a visual artist, researcher and community liaison. She works in response to notions of liberation and aesthetic irony, and is interested in the formation of underground religious groups and fringe-communities. She started Third Room in 2017 as a space for experimental exhibitions and diy-programming for young and underrepresented artists in Portland, OR. She is co-founder of "You Are Here”, a publication platform that centralized visual artist’s writing and criticism. She has exhibited work in Portland, Seattle, St. Louis, Chicago, New York and Beijing. Kalaija now lives in St. Louis, where she works as acting manager for The Luminary and is a member of MONACO, a cooperatively run gallery. She recently co-lead The Human Way, a free, virtual 12-week residency for artists around the globe to define and practice communal-care, with Prem Krishnamurthy and Home-Cooking.