The Black Market Sound: Sampling a Micropolitical Terrain of Listening, Resistance and Refusal

Masimba Hwati

August 2021

If there is an oxymoron, a vulgar beast hidden in plain sight in postcolonial Zimbabwe, it is the black market, an ever-shifting diabolic Wall Street located on the streets. As much as it is illegal, it is also financed and run by the kleptomaniac elites who still grease and oil the extractive capitalist and colonial machine they fought against forty years ago. What do we hear when we slow down and listen to the culture in these spaces where the nation’s wealth is captured and eaten by a select few? Here, desperate young men run illegal economic errands for a few rich people sitting in big government offices. The aesthetic, olfactory and sonic registers in the black market suggest the contradictory language of postcolonial aspiration to wealth and, at the same time, a biting critique of this broken system where the rich become richer and the poor become poorer.

How does one theorize constantly shifting socio-cultural and politico-economic conditions? For instance, take the muffled tones and habit of speaking through the teeth that characterize the black market trade of illegal foreign currency and street stock exchanges in Harare. Ximex Mall was the cradle of this dark trade back in 2008.1 The sonic registers and phonetics in this metropolitan zone are utterly unique. Even the sound made by the frantic speed at which the over-circulated, worn out, greased and grimed bank notes are counted and flipped to you during a transaction is very particular to these spaces. It takes Ninja skills to count money like that while the eyes are scanning the periphery for the city council police. Hushed voices and suspicion mixed with seduction dominate the atmosphere.

The young traders’ fashion is a political statement: tight pants, flat base caps, gold chains and rings, shiny shoes, semi-expensive fake watches and fake perfume aromas make the air so dense you can almost touch it. A hybrid of African American rap aesthetics and Congolese dandy fashion collide to create a new world. The young men don cheap, poorly drawn, regrettable tattoos made from the toxic milk of the African Milk Tree (Euphorbia trigona) ― locally known as Heji and planted in rows as hedges around houses as a deterrent against intruders ― or sometimes cheap India ink, creating another hierarchy of tattoos. In this catalogue of bad tattoos you find all sorts of images such as the swastika, which on the streets is called german never surrender and has allegedly been dissociated from its Nazi history to assume a new place in the pseudo-gangster aesthetic of the streets of Harare. There is an undeniable androgyny throughout as if to register a militant fluidity and stubborn shapeshifting agenda, a resistance to category, to knowledge, to Kurasisa vavengi John Cena-style:2 like an elusive and vengeful protagonist betrayed by a lover, a whole generation of young African people betrayed by their so-called revolutionary governments.

Ma-Changemoney is the name given to these young men who trade foreign currency and other commodities on the illegal market. The Changemoney carry about themselves a sound (think Tina Campt’s Listening to Images/bodies). Audible or not, you can hear it, smell it and feel it. It’s a hybrid sound: Koffi Olomide meets Lil Wayne, African American bling meets Parisian/Congolese flea markets and second-hand Bhero.3 When passing through the Changemoney zone, the aerosol-collage of genuine brands meets Chinese-made meets local-made perfumes characterizes the olfactory space. Panenge pachinzwika perfume dzakasiyana siyana. The Shona description of this olfactory environment uses sonic terminology.4 Kunzwa, a verb that comes from the root Nzeve (ear) in the previous phrase, conjugates to Nzwika (heard). You can hear the smell of the perfume just as you can hear the salt in your food or the sugar in your tea.

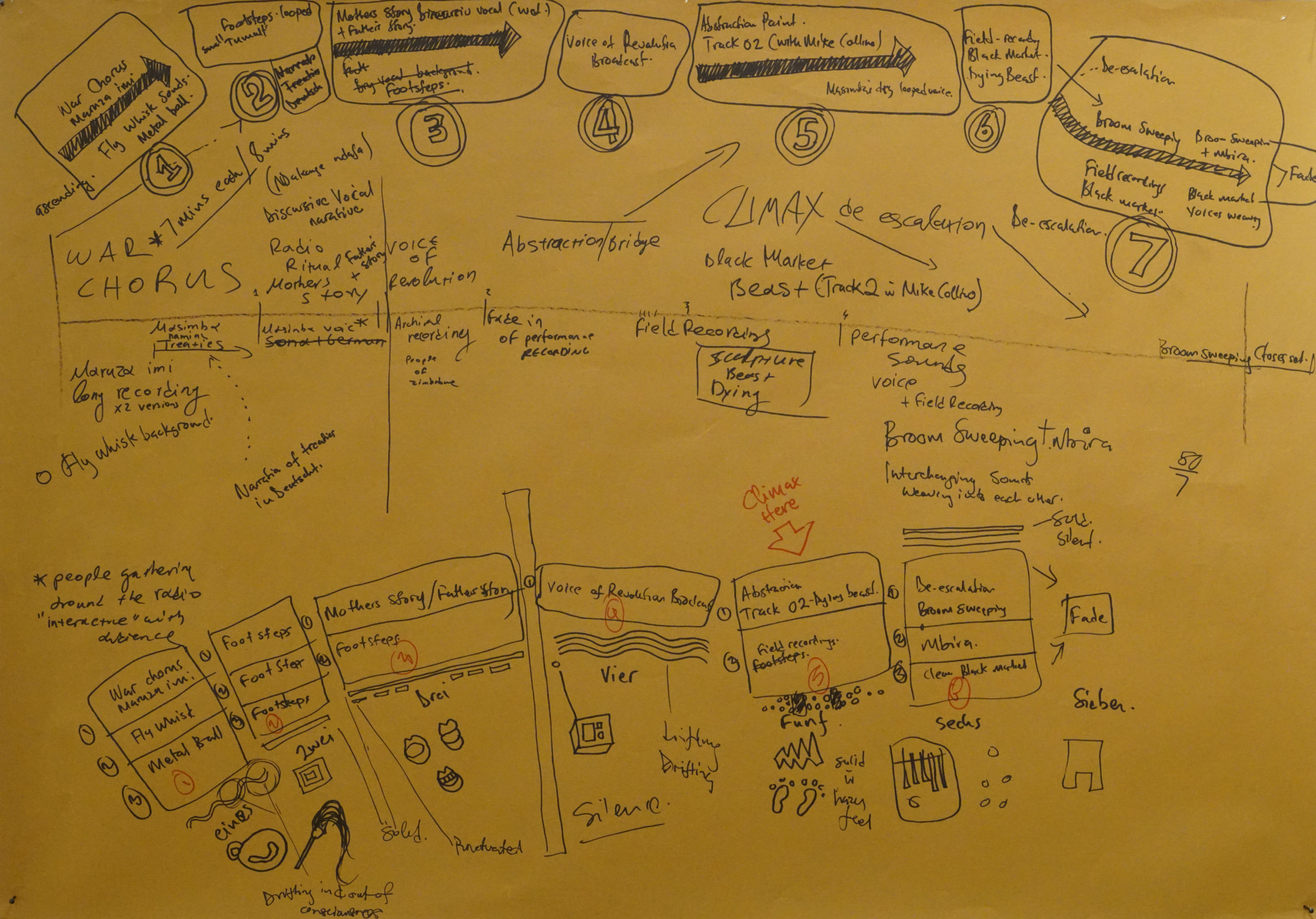

Black market score. Courtesy of the author.

The infra- and micropolitical statements conveyed by the sonic and phonic material in the black market opens up bigger questions around extractive violence in postcolonial state-making: in this case, in modern day Zimbabwe. The ad-hoc conditions and modes of production reveal how Shona philosophy thinks through sound and listening. The young, predominantly male, black market traders are locally described as vapfanha vasinganzwe and vapfana vanemisikanzwa. The persistent use of sonic/phonic terminology brings us to another noun, Misikanzwa (mischief/shenanigans/boundary pushing), where the root noun Nzeve (ear) is again transformed. These words transcend aurality/orality and point towards misalignment, refusal and resistance to a socio-cultural political norm.

The black market as a space is characterized by what Achille Mbembe calls political improvisation5―a state where people shapeshift and use whatever is available to them in order to survive. In Zimbabwe, the black market began flourishing around 2003 when hundreds of companies were forced to shut down alongside rising inflation.6 With fuel, food and foreign currency shortages, the black market soon grew to become not only an economic alternative but also a cultural space capable of producing and sustaining its own street lingua and etiquette that would eventually end up in ubiquitous urban circles. Here, you encounter the language of syncopation in the postcolonial thinking of Mazhet,7 Maghepu8 and recently Kungwavha-ngwavha.9 This is the political position of people who refuse death by an extractive colonial/postcolonial legislature, a posture of improvisation against the spectre of an inherited Rhodesian system.10

“In contrast to down beat marches the offbeat rhythms do not obey but resist. Moreover, they leave behind the phantasm of atomized egos, but instead become alive through the communal interlocking of various players. Instead of the phantasm of mechanized identical repetition they unfold their power through permanent variations and improvisations in the repetition which seems to stretch the bend of time.”

―MK on Ariel Flórez and Heidi Salaverría’s project “Syncopated Resistance”11

“The common denominator in all African American music is the rhythmical complexity of the syncope.”

―Ariel Flórez and Heidi Salaverría12

Sounding is the politics of occupying space and self-liberation. It is reminiscent of the Zoot Suit Riots on June 3-8, 1943, in Los Angeles when young Pachucos13 appeared―deliberately “being” present―in strategic, public spaces wearing zoot suits during World War II. This was deemed defiant and dangerous by State agents, and, during the week-long disturbances, U.S. Army personnel responded with violence against the Pachucos’ loud radical presence the same way Zimbabwe law enacts double standards through violent reactions to the black market. This sounding―using fashion and the body as both speaker and microphone―has the potential to generate frequencies, socio-cultural noise and feedback.

Masimba Hwati. “Rückspiegel.”

With these reference points, I’m persuaded to think that reviving ancestral cultures of sounding and deep listening might be the best way to understand the socio-economic, colonial trauma of postcolonial state crafting. Shona philosophy, which is so deeply rooted in sound and listening, shines a distant light and suggests a key. (The same could be said of most Sub-Saharan cultures and languages which have a deep affinity to sound.) In his book, The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World’s Wild Places, Bernie Krause posits that our early human ancestors navigated their way around their environments by deep and participatory listening.14 Such listening was a survival skill and still is today on the black market in Harare. Yet, the illegal market has an older and a more legitimate sister, the flea market.

Mupedzanhamo: Polyphony, Chaos and Spontaneous Synchronization

The use of loud music to lure customers is a common strategy at Mupedzanhamo in Mbare, Harare.15 These second-hand clothes flea markets, a common feature all over Sub-Saharan Africa, are known by various vernacular names in different African countries: in Ghana, obroni wawu (clothes of the dead white man); in Zambia, salaula (selecting from a bale by rummaging); in Nigeria, okirika (bend down boutique); in Kenya, kafa ulaya (clothes of the dead whites); and in Zimbabwe, Mupedzanhamo (where all problems end).16 Inside the walled, overpopulated, chaotic market at Mbare Msika, you experience an intense polyphonic bath, an aural offering beamed from several radio sets playing different genres of music all at once, co-mingled with the high-pitched calls of the vendors wooing customers, and mixed with the advertising shouts of roaming vendors with no fixed abode. The market vibrates on several levels, sometimes in haptic ways. “Touch is a move” is a rule in the game of ghetto checkers where you are penalized for mistakenly touching a piece. This rule is transferable in the flea market where the way you touch wares communicates your intention to just browse or to buy.

Sitting long enough within this aural/oral cosmos, one notices a fascinating spontaneous synchronization effect of the different sounds taking shape as a chorus of defiance, a refusal to be categorized as either music or noise. In their 2018 paper, “Spontaneous Synchronization and Nonequilibrium Statistical Mechanics of Coupled Phase Oscillators,” Stefano Gherardini, Shamik Gupta and Stefano Ruffo define spontaneous synchronization as “a remarkable collective effect observed in nature, whereby a population of oscillating units, which have diverse natural frequencies and are in weak interaction with one another, evolve to spontaneously exhibit collective oscillations at a common frequency.”17 Vibrating subjects, both human and non-human, seem to share a common consciousness regulated by a sonic medium and adjust their frequencies with an intelligent intuition beyond logic. There is an immaculate sense of order that sustains this polyphonic chaos, a milieu typical of many African flea markets where sonic facts and the poetry of socio-economic historical consequences merge. This convergence engages primarily with an auralilty that demands us to slow down and listen deeply. But how do you position yourself to listen to, with, in and around such a complex, opaque and yet noisy environment?

Masimba Hwati.

This Mupedzanhamo universe seems to demand a specific type of listening that is neither ethnographic nor autobiographical. It demands a type of immanent locating where the listener positions themselves within, without, beside, above and below the social acoustic space. Rastafarian counter lingua proposes a listening position known as “overstanding,” a word coined in anticolonial circles in the 60s, as a critical response to the conventional term “understanding,” to mean something broader, like getting “the big picture,” and “adds vibrations of positivity, strength and respect.”18 The term is also a direct subversion of hierarchy, literally changing from “being under” to “being over.” However, the polyphonic soup in a Mupedzanhamo demands listening that is fluid and trans-locative―that allows an omni-aural response to time and space, a slowing down, an immersion and a detachment. This is why attempts to theorize this sonic complexity almost always fail. One has to be willing to sit with the contradictions and tensions of the socio-political and cultural matrix that give birth to these soundscapes, immersing the body in these postcolonial markets. The opacity of these oral and audible environments defies the easy conception of sound as an ethnographic tool to study a society. The twists and turns, disjunctures, breaks and false leads demand a humble admission that one might never really figure out what is actually happening.

In The Great Animal Orchestra, Bernie Krause further proposes that in order for various species of animals and insects to communicate together amongst their kind, they tune-in on an open channel (or bandwidth) of frequencies that do not clash with other species.19 In this way, one species can hear each other across the sonic fabric while a myriad of other species use different frequencies to communicate simultaneously. Similarly, in the black market, quotidian conversations continue even in such a chaotic and noisy place. All kinds of conversations―from low frequency romantic and semi-legal deals to high pitched gossip and street preaching―seem to locate themselves in this sonic configuration with co-existent ease. The high-pitched shouts of the Hwindi pierces the atmosphere with insidious violence.20 Just like the Changemoney, the omnibus tout has his place in the urban sonic milieu―and every other noise seems to configure itself around his fast-paced voice, another illegal player in the postcolonial economy, a social subject created by the broken, extractive ghost of a system that refuses to die.

Sonic Territorial Marking in Postcolonial Zimbabwe’s Restricted Spaces

As you exit the city center heading southwest, you reach Highfields ghetto, a black suburb with working class residential pockets, and the place where I grew up. In the 1930s, Highfields was constructed by the Southern Rhodesian government as a segregated township to accommodate black laborers and their families during colonial times. The township (the second oldest in Harare) was home to workers employed in the nearby industrial zones of Workington and Southerton―just as Mbare, the oldest formal black suburb, had been built to accommodate black workers employed in Workington and Graniteside―as domestic labor to white households in the city’s northern and western suburbs. The presumably affluent parts of Highfields are located in Old Highfields, namely The Stands, 12 Pounds, and 5 Pounds. While the latter names are associated with the initial purchase price of a home in Rhodesian (British) pounds, The Stands, locally called Kuma Stands, got its name because “when first sold, the area was a greenfield and residents had to build houses of their choice on the new Stands; this is in comparison to the other areas of Highfields where the government had built low-cost basic housing,” for the indigenous colonized population, “and sold it at reflective prices.”21 Historically, the yard areas in Kuma Stands are relatively large and the houses, arguably flamboyant and indulgent, reflect the affluent status of the black Rhodesians who settled here.

One of the distinguishing factors between the so-called affluent and not so affluent partitions of these areas is the sonic atmosphere. Until recently, the soundscape in Kuma Stands was quite subdued as decibel levels were controlled by several cultural and social apparatuses, an aural panopticon and deafening silence that caused one to be hyper self-aware. This area was always clean, and everybody knew how to behave themselves (sonic-wise); only sometimes you would hear a dog barking and the chitchatter of the maids and “garden boys” behind high durawalls. In these places, even the Mutsvairo22 vendors didn’t shout. If they ever ventured to sell their brooms in these parts they would gently knock on the iron gate or would respectfully press the intercom. This is one example of the colonial curation of sound lingering even after the political independence in Zimbabwe. The high walls that partition and fragment the houses, the solid iron gates and Cartesian arrangement of stands and yards, including the cultural architecture, carries with it a colonial silencing, suppression and ordering. The nights were especially sonically deadened compared to other parts of town where tower lights extended daytime activities and soccer matches would continue until midnight―living up to the name Harare, derived from Haarare meaning the one who does not sleep.

Fortunately, our home was located outside of these sonically oppressed zones of Old Highfields and was not considered affluent according to the adopted repressive colonial paradigms that shaped the town planning and post-independence social architecture. The ghetto sonic-scape in which I grew up was well textured and loud. It was an un-curated, spontaneous soundscape, a collage of the voices including floor polish vendors singing “Cobra ye red ne black ne white-Cobra” in F# minor, the ad-hoc falsetto of the Okra vendor’s “Dereeeere,” and the improvised shrill Namamapoto song of pots and pans. Every Saturday morning, you would hear the klink and klang of kitchenware (of the Kango brand from Treger, a Rhodesian company that made tin household wares coated with enamel) as neighbors pulled out their damaged goods for the repairman, followed by the hissing and sizzling of oxygen and acetylene melting the brass soldering wire used to repair them, and leaving brown and yellow enamel teapots and pots with shiny, random brass spots on the bottom. This was not only an oral/aural affair, but also an olfactory one as the specialized gases used to solder created a scent of their own.

Masimba Hwati. “Putugadzike (tea),” 2016. Photo courtesy of Smac Gallery.

In “Putugadzike (tea)” (2016), I reference the aforementioned aural and olfactory urban ritual. The installation consists of a large checkerboard suspended mid-air with steel cable topped with various contraptions made of different types of teapots. I’m attracted to the symbolism of these objects and the way they reference many stories and places. For instance, the enamel teapots I used open up not only the narrative of how the British brought tea to Zimbabwe but also the longer history of tea bought from Chinese traders and Portuguese missionaries. Also of personal importance was the Saturday morning ritual when we would sit on the veranda in the sun to drink tea. In those moments, the sound of the metal teaspoon stirring to the sound of the enamel klink klank was the sound of gathering and communion.

At the same time, what is both more interesting and disturbing is the complicity and acquiescence of indigenous people to these lingering colonial vestments of social engineering. As kids growing up in the euphoria of a young national independence, our juvenile minds were conditioned to aspire to the quiet, civilized standard of 5 Pounds, 12 Pounds and the Kuma Stands areas. Noise was considered uncivilized and Chiruzevha-like.23 In my early days at school, I was always on the list of noisemakers to be punished every Friday by watering the school’s vegetable garden. As kids, we offered some disruptive interventions to mediate the sonic oppression; some days after school we would ride our bikes to these quiet and “civilized” neighborhoods and press the intercoms frantically before running for dear life. Sometimes, we would do a drive-by pelting of the iron gates with stones and pebbles; other times, we would perform a random shouting exercise and run before the maids and garden boys released the dogs on us. The houses unfortunate enough to have metal trash cans outside would experience the full sonic wrath of the lid against their iron gate, tarmac or concrete pavement. This was a sonic marking of territory and a registration of our presence through noise and disruption.

Masimba Hwati, “Dzikamunhenga.”

Mhoze Chikowero documents similar interventions on the streets of Harare as the POVO (black politically conscious population) marched on Independence Day, from Ambassador Hotel to First Street, strategically targeting places where black African people had been banned or restricted from populating. These were the politics of occupying space and of sonic mapping. Prior to political independence in Zimbabwe, First Street and other parts of the city were considered no-go areas for black people, and silence was one of the characteristics governing these spaces. Chikowero writes:

Their loud, celebratory mass occupation of and toyi-toying24 through the cities was therefore a climactic performance of decolonization and decomposition of self: the taking back of power, space, and their alienated voices and identities. Their songs swallowed the city in a sonic counterassault that was both visceral and therapeutic.25

As Julian Henriques wrote on the Jamaican reggae sound system, the sounds become embodied and framed the entire sensorium: “Sound at this level cannot but touch you and connect you to your body. [It’s] not just heard in the ears, but [it is] felt over the entire surface of the skin.”26

At four o’clock in the afternoon, the day comes to a rough end on the streets, and another one begins. The city council police officially closes its office where they arrest street vendors and Changemoneys, confiscating their wares, and ceases all patrols. Harare comes alive again with all sorts of pop-up markets. On the streets this is called kupfapfauka―the sound and seizures made by a slaughtered chicken, even after the head has been severed―a sound of struggling, neither dead nor alive yet hanging in that liminal zone. Here you find flea markets selling everything from second-hand brasseries and Jockey and Calvin Klein underwear to pre-owned, donated T-shirts from all over the Midwestern United States (Universities of Minnesota, Iowa, Michigan); a Rotary Club in Madison, Winscosin; hoodies from the Arkansas Razorbacks; and baseball caps from New York Yankees or Boston Red Sox. Playing on loud boomboxes connected to phones via bluetooth, the music is just as diverse as the contents of the Bhero: Oliver Mtukudzi and the Black Spirits plays alongside Tupac Shakur and Dolly Parton.

In this nocturnal cacophony, you also find street food delicacies such as Madora (roasted Mopani worms with chilli), chicken offal roast, roasted corn and expired tinned beans, Cerevita and Lucky Star canned fish with dubious labels. Among these, you also find the infamous drug of the ghetto youth, Guka Makafela.27 These, and many other diverse wares, creep and slide their way into the heart of the city at night, reactivating yet another chaotic late-night re-mix buzzing with all sorts of people marking economic and political territory. Vibing with low frequency and ASMR tones, you hear the black market sound―a sound of seduction and struggle, of desperate refusal and improvisation.

Footnotes

- Ximex Mall started out as a car showroom before it was converted into a department store and then a shopping mall. From around 2008, the mall housed shops selling designer wear (such as South Central), trendy hair salons and internet cafes. It was commonly referred to as “the dealer’s paradise” because of the concentration of black market traders for goods such as illegal foreign currency, phones, iPads, laptops and other electronic gadgets. In 2015, the mall was demolished by the Harare city council, and the proprietors converted it into a car park. However, the former tenants did not disappear. Instead, they took up positions around the car park and continued with their trade. This resulted in all sorts of things being sold there ― from liquor to drugs and cars. Gamblers also appeared. The market also became a pop-up car wash and car boot sales venue.

- Harare Slang loosely translated to “confuse your enemies” derived from artist Sho Madjozi’s John Cena album (2019), Genres: Gqom, HipHop/Rap. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H9bGITkIHmM.

- Bhero is a Shona translation of the name of a bale of second-hand clothes donated from North America and Europe that are tightly packed and shipped to be sold in third world African countries weighing from 45kgs to 100kgs.

- Shona are a group of culturally similar Bantu-speaking peoples living chiefly in the eastern half of Zimbabwe.

- Achille Mbembe, On the Postcolony (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

- “TIMELINE: Chronology of Zimbabwe’s economic crisis,” Reuters, September 19, 2007, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-zimbabwe-inflation/timeline-chronology-of-zimbabwes-economic-crisis-idUSL1992587420070919.

- Zimbabwean street lingo for semi-legal deals or enterprises.

- Zimbabwean street lingo for “gaps” in reference to economic openings and cracks in the system.

- Recently coined Zimbabwean street lingo for economic improvisation, i.e. to hustle hard.

- Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, also called Central African Federation: a political unit created in 1953 and ended on Dec 31, 1963, that embraced the British settler-dominated colony of Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and the territories of Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and Nyasaland (Malawi), which were under the control of the British Colonial Office. Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia, “Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland,” Encyclopedia Britannica, January 6, 2011. https://tinyurl.com/588hdpu3.

- MK, “Heidi Salaverría / Ariel Flórez Syncopated Resistance Rhythms of Post-Colonial Thinking,” Hycp, February 11, 2018. https://tinyurl.com/s9uadvah.

- Ariel Flórez and Heidi Salaverría qtd. in MK, “Heidi Salaverría / Ariel Flórez Syncopated Resistance Rhythms of Post-Colonial Thinking,” Hycp, February 11, 2018. https://tinyurl.com/s9uadvah.

- Pachucos are male members of a counterculture associated with zoot suit fashion, jazz and swing music, a distinct dialect known as caló, and self-empowerment in rejecting assimilation into Anglo-American society that emerged in El Paso, TX, in the late 1930s.

- Bernie Krause, The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World’s Wild Places (New York: Little, Brown, 2012).

- Mbare is a high-density, southern suburb of Harare, Zimbabwe. It was the first high-density suburb (township), established in 1907 by the Colonial Government.

- “Every day, the sorting of clothes across Europe processes hundreds of thousands of tons of unwanted textiles. Overproduction strengthens charity foundations which, through redistribution, transform them into new capital. Unaware fashion consumers, getting rid of excess clothing are convinced of the purpose and importance of apparent recycling. In fact, the supply significantly exceeds demand. In the common belief, the global south is still a viable market. However, clothing sent from the rich north destroys the basics of the textile industry in many countries of Latin America and Africa. Excess and false belief about the deliberate action of Western societies can be seen in the descriptive language by which local communities define our apparent altruism.” Weronika Wysocka, “Where All Problems End/Mupedzanhamo,” project description at https://tinyurl.com/hmz6yjdn.

- Stefano Gherardini, Shamik Gupta, and Stefano Ruffo, “Spontaneous synchronisation and nonequilibrium statistical mechanics of coupled phase oscillators,” in Contemporary Physics 59 (2018). DOI: 10.1080/00107514.2018.1464100.

- “Peace, Love, and Understanding,” Marley Natural blog post, https://tinyurl.com/ftn8fk68.

- Bernie Krause, The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World’s Wild Places (New York: Little, Brown, 2012).

- Slang for omnibus conductors. These unemployed youth in Harare specialize in shouting to coerce prospective passengers in the omnibuses around the city and the various neighborhoods. They are known for uncouth language, and they are the inventors and custodian of new street lingua in Harare.

- “Highfield, Harare,” Wikipedia, last modified April 10, 2021, https://tinyurl.com/fbxacym3.

- Shona for traditional, homemade hand brooms.

- The word Ruzevha is bastardized English for “Reserve,” which is a dry and arid area that the indigenous Zimbabweans were forcefully displaced to by the colonial government via a legislative instrument called the Land Apportionment Act of 1930, which made it illegal for Africans to purchase land outside of established Native Purchase Areas. These were places of suffering and acute poverty which became synonymous with black peoples’ precincts.

- Toyi-toyi is a Southern African dance originally created in South Africa by the African National Congress (ANC) during Apartheid. The dance is used in political protests in South Africa and Zimbabwe. Toyi-toyi includes foot stomping and spontaneous chanting during protests that may include political slogans or songs, either improvised or previously created.

- Mhoze Chikowero, “The Afrosonic Making of Zimbabwe,” in The Chimurenga Military Entertainment Complex, publication forthcoming.

- Julian Henriques, “Sonic Dominance and the Reggae Sound System Session,” Auditory Culture Reader, M. Bill and L. Back, eds. (Oxford, 2003): 452.

- Guka Makafela is the Zimbabwean slang name for the illicit drug crystal meth, also referred to as Mutoriro. One cannot smoke Guka Makafela without the aid of disused “energy saver” bulbs. These bulbs, which are usually white, have the white powder spotlessly cleaned off to be sold to those who want to smoke. Like Shisha pipes found at uptown bars, the energy saver bulbs are used by the ghetto youth.

Masimba Hwati works across sculpture, sound, performance, video and text. He holds an MFA from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor and is a PhD in Art Practice candidate at the Academy of Fine Art Vienna. He attended Skowhegan School of painting and Sculpture in 2019. He studied and taught sculpture at Harare Polytechnic in Zimbabwe. Collections include: University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA), Iziko South African National Gallery, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Scott White Contemporary (San Diego, CA), Jorge M. Perez Collection (Miami, FL), George R. Nnamdi Collection (Detroit, MI), National Gallery of Zimbabwe, and the Gervanne & Matthias Leridon Collection. In 2015, he exhibited at the Zimbabwe Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale. He is an honorary research fellow at Rhodes University, Fine Arts Department in Grahamstown, South Africa. He has had solo and group shows in Belgium, Zimbabwe, South Africa, United States, France, Canada, and in Berlin and Weimar, Germany.