Atlanta: Notes from the Album

Serubiri Moses

September 2021

Nine African American women, full-length portrait, seated on steps of a building at Atlanta University, Georgia. Photographer: Thomas E. Askew. Collection: African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition. Date: 1899/1900. Library of Congress Prints and Drawing Division.

1.

In David Levering Lewis’s biography of William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, the author describes Du Bois’s physique as he goes out to play tennis in the late 1890s at Atlanta University from the viewpoint of his sociology students (many of whom are black women): “The figure he cut on the tennis court won him high marks from female students, some of whom had begun calling him ‘Dube’ behind his back.”1 This W. E. B. Du Bois – a Du Bois with “swagger” – is not the one I am used to, and yet there he was on the tennis court in the sweltering Georgia heat. According to his biographer, “Will was lightly muscled, with fine buttocks and well-shaped calves that filled tennis whites appealingly.”2 The black women watching were bowled over by his athletic prowess, his “attack” on the court and his sporty enthusiasm. Some wondered what this sporty man had done with their professor of sociology.

Four African American women seated on steps of a building at Atlanta University, Georgia. Photographer: Thomas E. Askew. Date: 1899/1900. Collection: African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition. Date: 1899/1900. Library of Congress Prints and Drawing Division.

2.

Black folk were often caricatured in song and dance, but hardly were they depicted reading. Reports on black literary publishing in nineteenth-century Georgia reveal the paucity of data available on black readership.3 Thus, black literacy was a monumental struggle before and after the Civil War. Having moved from Philadelphia to teach at Atlanta University in Georgia, Du Bois fought back against the media’s depiction of black folk by using science to confront ignorance, and thus turned to the “ivory tower of race.”4 While scholar Steven Shapin has explained that the idea of an ivory tower “was always a figure of speech,”5 understood as the university, it is also a striking and poetic description that evokes images of the Eiffel Tower, Big Ben, and ancient obelisks. (Would this “ivory tower of race” be made of elephant tusk?) However, in Lewis’s biography it becomes very clear that Du Bois’s ivory tower shields from the weather of the South – that is, the climate of racial antagonism. In the same way, the “ivory tower of race” becomes both a figurative symbol of black literacy and black readership, and alludes to the ways in which Du Bois threw himself into lectures and research at Atlanta University.

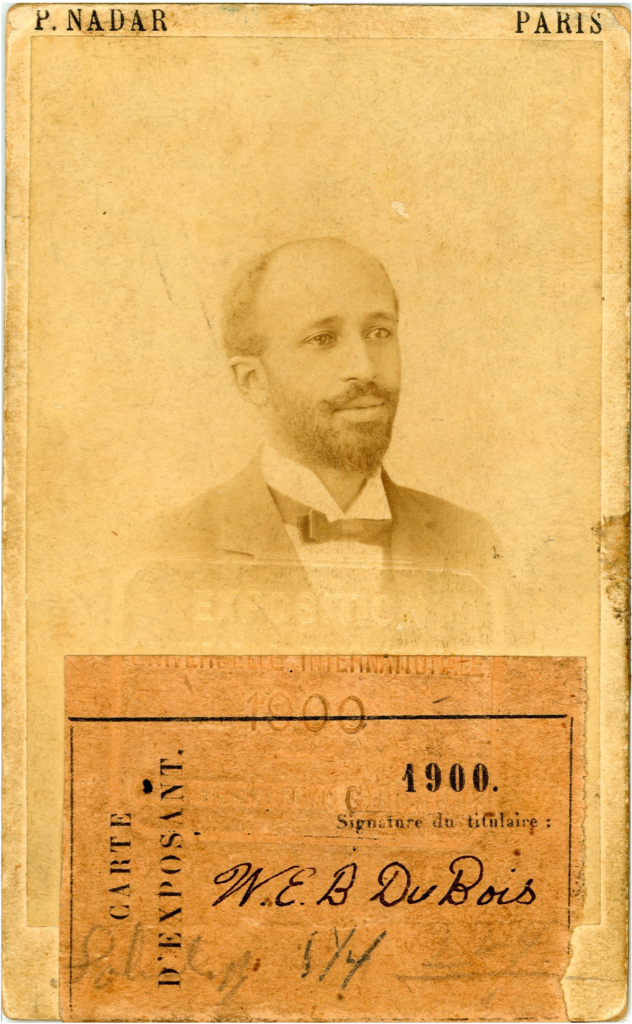

Exhibitor Card (of W. E. B. Du Bois), Paris Universal Exhibition. Photographer: P. Nadar. 1900. Source: W. E. B. Du Bois Papers.

3.

French pioneers in photography, the Nadars, had the distinct honor of photographing “Will.” The elder Nadar, born Gaspar-Félix Tourchardon (1820-1910) and said to have organized one of the first exhibitions of Impressionist painting in the capital city of Paris, was a central figure in the art world at the time. The story goes that because Nadar was an older and ailing man of the arts and letters, his son P. Nadar (1856-1939) ran his gigantic Paris studio. Securing the job to make the photo IDs of the exhibitors at the Paris Exposition, P. Nadar had the distinct honor of making Du Bois’s Exhibitor card for the 1900 Paris Exposition (pictured above) and photographing one of America’s most brilliant thinkers.

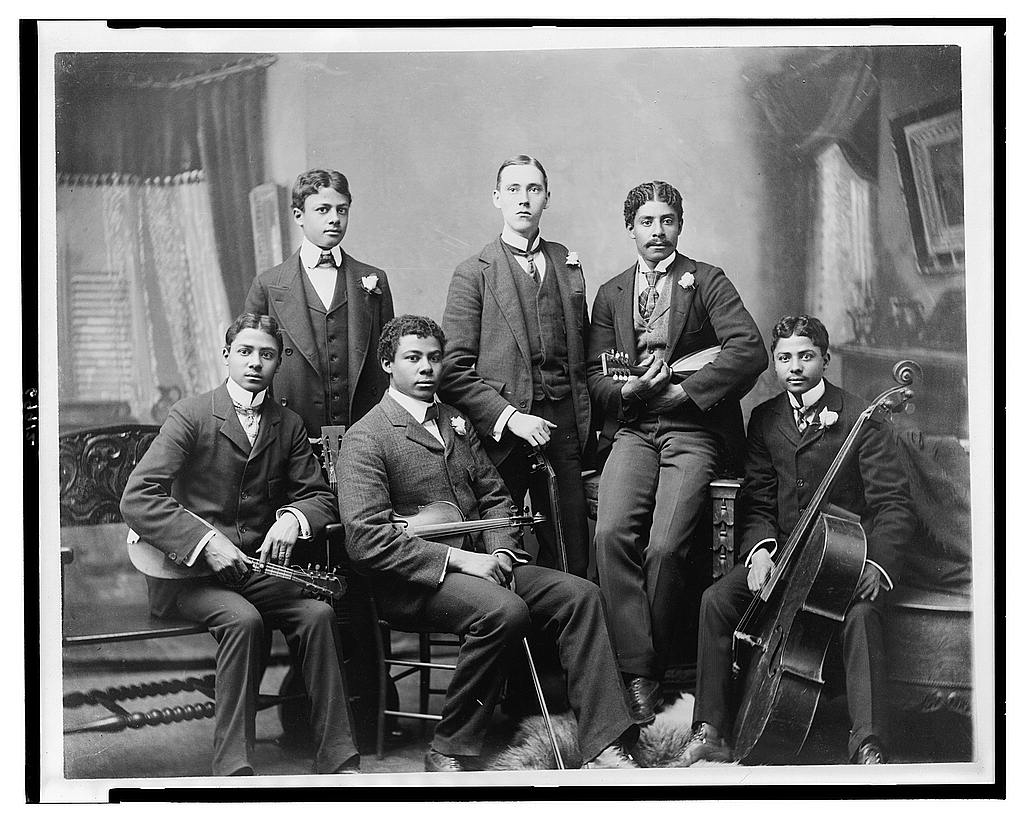

Summit Avenue Ensemble, Atlanta, Georgia. Date: 1899/1900. Photographer: Thomas E. Askew. Collection: African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition. Library of Congress Painting and Drawing Division.

4.

As the “compiler” of the American Negro Exhibit at the Paris Exposition Universelle, Du Bois hired black photographer Thomas E. Askew to create an album of African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia. To tell the story of a photographer is to tell the story of all the souls he or she captured. The fact that photographs live on while the people whose souls they captured pass on is remarkable. No wonder photographs would be approached by some nineteenth- and twentieth-century Africans with caution. South African photographer and writer Santu Mofokeng explained that “because to some people photographs contain the ‘shadow’ of the subject, they are carefully guarded from the ill-will of witches and enemies.”6 What, then, is the story of the (black) photographer, except as another ghost among the many ghosts he or she intentionally captured, some willingly, others unwillingly? Thomas E. Askew, whose powerful images featured in Du Bois and Thomas J. Calloway’s American Negro Exhibit, is little known or researched. However, in her landmark book Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers, art historian and photographer Deborah Willis makes note of Askew’s mastery of lighting and composition, as well as his concern for portraying his subjects accurately.7

5.

In the 2014 film based on Deborah Willis’s previously mentioned book, Through A Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People, artist and filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris narrates that his grandfather placed their family photographs next to the images of Frederick Douglass in the family album. I have often thought about what it means to imagine yourself in the lineage of Black liberation, about what it means to be in dialogue with Frederick Douglass via the photo album. The family albums of my childhood are the one my father kept, the one my mother kept, and a wedding album that graced our living room. My father’s album included pictures of himself in high school (in bell bottoms and afro, or posing with a guitar in the late ’60s), photographs of his mother (regal in appearance), his father (dressed up in military fatigue – I once asked if my grandfather had a stint in the army that I didn’t know about, and my father said he was only pretending for the camera), and his older half-sisters. All are dead now, except my father. My mother’s album contained not only images of her sisters (some have since died) and her cousin Emmy-Lou (a painter and musician), but also her time in London in the ’80s. In the album, her sisters are at home (on the balcony) or elsewhere, in Italy, where one of her elder sisters went to pursue her graduate studies. Unlike my own family photo albums that kept stories (some about fashion, casual moments, and others about family history), Harris’s family album actually sits in a tradition of the “scrapbook,” which can be described, in the broader sense, as an archive.8 As such, the family album as a scrapbook has the potential to produce political memory and kinship across time with ancestors such as Douglass.

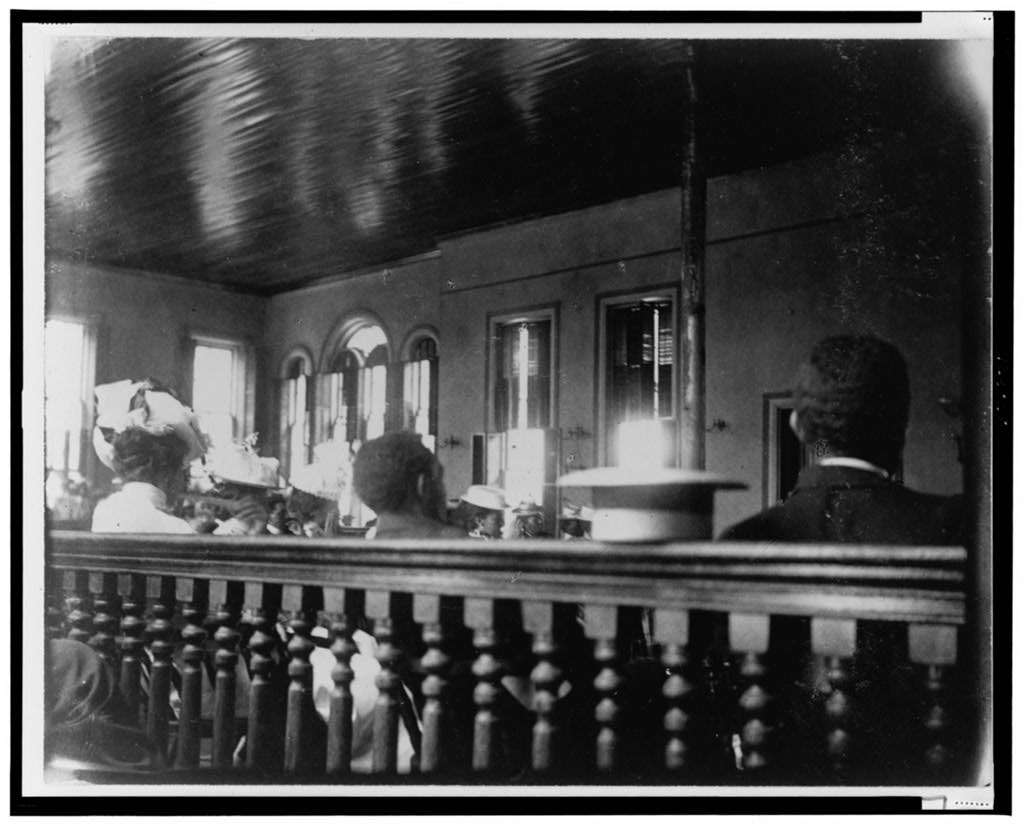

African Americans in church in Georgia. Date: 1899/1900. Collection: African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition. Library of Congress Painting and Drawing Division.

6.

If Du Bois had an apprenticeship during which he would seriously theorize black life, perhaps it happened after Harvard in the black churches of Philadelphia. At another quite unexpected moment in Lewis’s biography, he narrates Du Bois’s purported decision to “leave” philosophy and his choice to focus on sociology.9 Lewis describes the influence that Du Bois’s professor at Harvard, philosopher William James, had on him and credits James with having convinced Du Bois that a career in philosophy would not suit him. This moment of career guidance significantly altered the course of twentieth-century intellectual thought. Du Bois’s turn to the more accommodating profession as a professor of sociology at Atlanta University and the sociological research that followed informed his concept of the “color line,” which Du Bois identified at the Pan African Convention at Westminster Hall, London, as “the problem of the twentieth century.”10

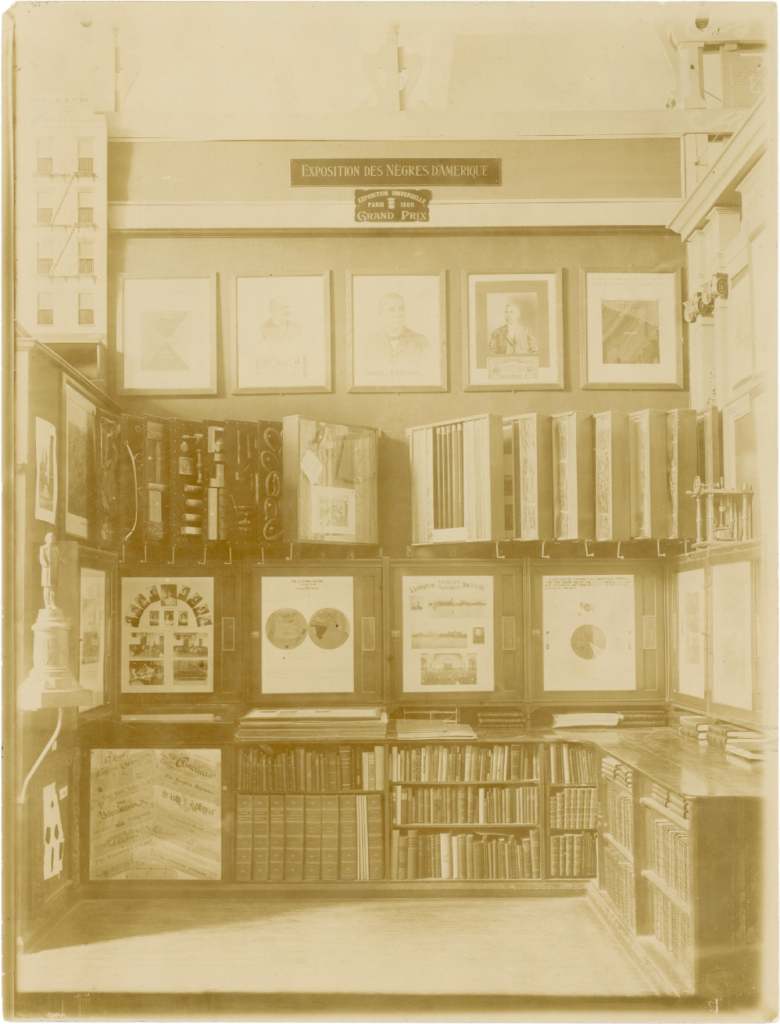

American Negro Exhibit installation at Paris Exposition. Date: 1900. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers.

7.

While Du Bois had earlier worked in the philosophy department at Harvard during his doctoral studies, at the turn of the century he was in Paris at the Rue des Nations presenting his ambitious research, developed at Atlanta University, in “a large plain white building where the promoters of the Paris Exposition [had] housed the world’s ideas of sociology.”11 His essay accompanying the Paris exhibition, “The American Negro at Paris,” has a clear emphasis on “progress,” a topic more aligned with philosophy than sociology (see, for example, Hegel’s Lectures on the Philosophy of History), which Du Bois would “illustrate” using scientific rigor in charts and photographs that proved that African American progress was viable at the highest level. Yet such research appeared at odds with the social sciences in the late nineteenth century which were deeply steeped in pseudo-scientific methods such as using the measurements of human craniums to judge intelligence or evolutionary development. Du Bois’s meticulous credentials would rival any specialist invited to the expo’s American and social science pavilions, yet his disappointment in the Rue des Nations pavilion also shows us a battle of the wills: Was he a sociologist or a philosopher? Was he doing sociology proper, or was he pursuing his philosophical ideas under the cover of sociological research? Might this disappointment reflect something about his attitude or at least his pride? It is worth noting that, regarding Du Bois’s famous study of African Americans in Philadelphia, The Philadelphia Negro, even his biographer justifiably pushes back on Du Bois’s brilliant research for his lack of interest in his black subjects’ own narratives.12

Thomas E. Askew, self-portrait. Photographer: Thomas E. Askew. Date: 1899/1900. Collection: African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition. Library of Congress Painting and Drawing Division.

8.

Thomas E. Askew’s contribution to the American Negro Exhibit is clearly delineated in the albums Negro Life in Georgia and Types of American Negroes.13 These images can be alarming, and indeed, according to historian Shawn Michelle Smith, reminiscent of mugshots.14 Yet, Askew produced startlingly glamorous portraits breaking the conventions of nineteenth-century anthropological, medical and indexical photography. By comparison, the Swiss-American biologist and Harvard scientist Louis Agassiz reinforced an anthropological vision of photography at the time. In 1850, Agassiz commissioned “distressing pictures of enslaved African Americans” that were “meant to support racist theories about the inferiority of Black people. Many of the sitters are naked or half naked and depicted as anthropological specimens rather than individuals.”15 In 1899, Askew took on the assignment to make photographs of “Types of American Negroes” via a self-portrait that says as much about his pride as his place in the world: defiance and self-narration comes through in the image (above). Yet I wonder: Does Askew emerge unscathed from the violence of scientific objectivity? Is he unscathed from the deductions and conclusions of historical progress?

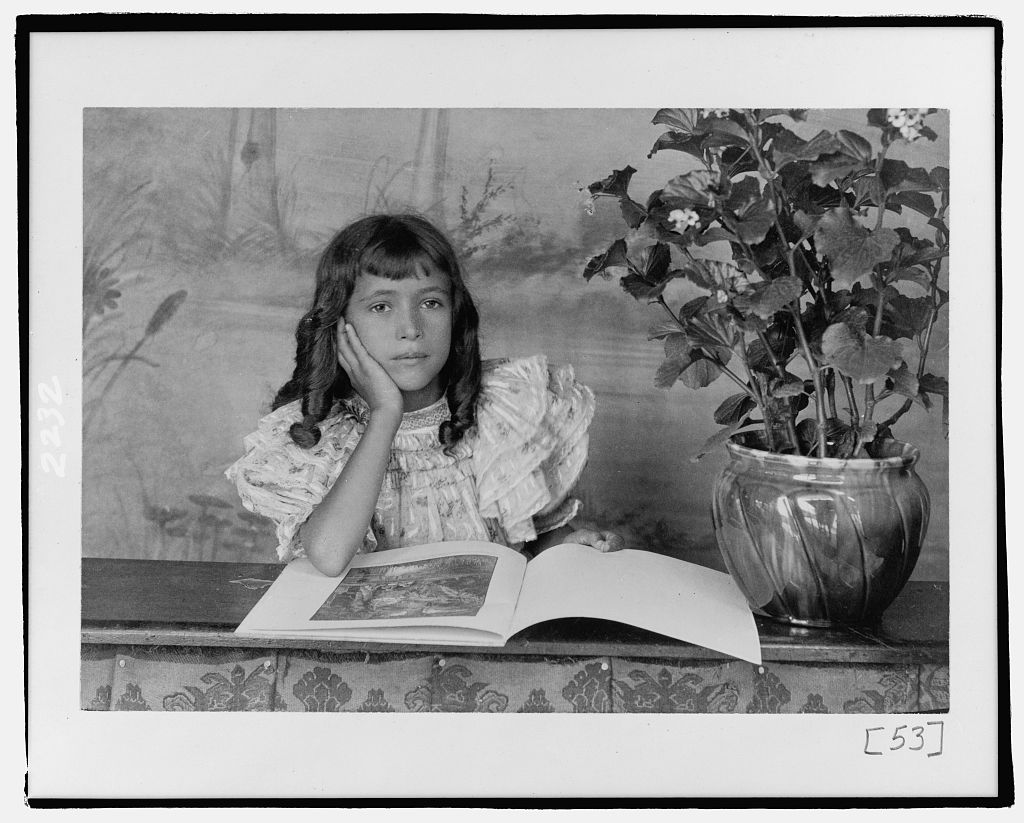

Daughter of Thomas E. Askew, head-and-shoulders portrait, seated, with open book. Date: 1899/1900. Photographer: Thomas E. Askew. Collection: African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition. Library of Congress Painting and Drawing Division.

9.

Du Bois, Calloway, and Askew’s activist archives function as foils to Agassiz’s dehumanizing experiments from the same period. Curator Brian Wallis has since demystified the nature of the experiments in an essay titled “Black Bodies, White Science,”16 and photographer Carrie Mae Weems has made a significant intervention into Agassiz’s collection by attempting to reclaim the voices of the sitters in her powerful collection of 33 toned prints, “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried” (1995-1996). The activist archive, with its mission of historical progress, used scientific evidence to fight ignorance, but Weems and others who have confronted Agassiz head-on by appropriating his images forgo black respectability in order to bring attention to the racial violence inherent in science itself. It appears to me that the American Negro Exhibit (1900) and its curator Du Bois, adhere to scientific protocols and objectives, however unorthodox they are in their posture of historical and archival activism. Du Bois’s “swagger” may have doubled in the field of science, breaking the conventions of a discipline that, according to Weems, made the black person “an anthropological debate.”17 Yet whereas Weems aimed at exposing how white America “saw itself in relation to the Black subject,” Du Bois and his co-conspirators performed what can be called an “ontological strike,”18 and they did so by disavowing the racism of the social sciences.

Footnotes

- David Levering Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868-1919 (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1993), 216. In his sociological theory of double consciousness, W. E. B. Du Bois argues that we are not always as the other sees us – and even though we would like to be seen by the other, we may never be seen accurately or truthfully.

- Ibid.

- Hortense Spillers, “Moving on Down the Line: Variations in the African American Sermon,” in Black, White, and In Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 251-276.

- Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 213.

- Steven Shapin, “The Ivory Tower: the history of a figure of speech and its cultural uses,” in The British Journal for the History of Science (2012): 1-27.

- Santu Mofokeng, “The black photo album/look at me: 1890-1900s,” in NKA: Journal of Contemporary African Art vol. 4, no. 1 (1996), 54-57.

- Deborah Willis, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers from 1840 to Present (New York: Norton, 2000), 14.

- I use this term in order to reference the way Du Bois used academic work to transform racial prejudice. This exhibition and its photographic archive must be read in dialogue with Du Bois’s politics, as stated in his public speeches at the Pan African Convention of 1900 and seen in his role in black politics in the United States as part of the NAACP.

- Lewis wrote that though Du Bois would eventually take his advanced degrees in the department of history, he nevertheless was drawn to the philosophy department and in particular to philosopher William James. The biographer also reports that Du Bois was a frequent guest in the house of William James, and that it was James who had secured Du Bois’s place in The Philosophy Club, a student organization at Harvard. Lewis also wrote quoting William James’s advice to the young Du Bois, “No man without independent means, certainly not a man dedicating his life to programmatic uplift of a disadvantaged race, should become a philosophy professor, James told Du Bois in his senior year, advice Professor Chase at Fisk had also volunteered.” See: Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 86-92.

- W. E. B. Du Bois, “To The Nations of the World” (1900), https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1900-w-e-b-du-bois-nations-world/.

- W. E. B. Du Bois, “The American Negro at Paris, 1900,” in Review of Reviews (1900): 575-77.

- “The history and sociology of (his subjects’) conditions interested Du Bois, not their individual, bruised-flesh lives. What the Philadelphia Negro thought about present and future Philadelphia he or she was not invited to say.” See: Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 205.

- Collection: African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition. Compiled by W. E. B. Du Bois. Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/2uavtp5r.

- Shawn Michelle Smith, “’Looking at One’s Self through the Eyes of Others’: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Photographs for the 1900 Paris Exposition,” in African American Review 34, no. 4 (2000): 581-599.

- “211: Carrie Mae Weems: From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried,” Museum of Modern Art, https://tinyurl.com/y2fbkn5h.

- Brian Wallis, “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes,” in American Art vol. 9, no. 2 (1995): 39-61.

- Speaking on her artwork From Here I Saw What Happened And I Cried (1995-6) Carrie Mae Weems said, “I used this idea of ‘I saw you’ and ‘You became’ as a way of both speaking out of the image and to the subject of the image. For instance, I say, ‘You became an anthropological debate and a photographic subject.’ I am trying to heighten the kind of critical awareness around the way in which these photographs were intended and then of course they are ultimately used by me. A strategy that I hope gives the subject another level of humanity, and another level of dignity that was originally missing in the photograph.” See: The Museum of Modern Art, “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried. 1995 | SEEING THROUGH PHOTOGRAPHS,” YouTube video, 2:32, 13 Feb. 2019, https://youtu.be/QxLvKarmz-I.

- This term is adapted from Afro-Brazilian artist and theorist Jota Mombaça’s term “Ontological Strike.” It describes the process of reproducing the ontological regime which forcefully makes Black or queer subjects hyper-visible. See: Jota Mombaça, “For an Ontological Strike” in We Don’t Need Another Hero: 10th Berlin Biennial of Contemporary Art (Berlin: Distanz, 2018): 42-50.

Serubiri Moses is an independent writer, curator, and educator based in New York. He is co-curator of the 5th perennial contemporary art survey, Greater New York (2021), founded in 2000 at MoMA PS1, Long Island City, and previously was on the curatorial team of the 10th Berlin Biennale of Contemporary Art (2018). His current research focuses on theories in African visual art and art exhibitions.