Making Power in the Desert of Whiteness: Jordan Weber’s Prototype for poetry vs rhetoric (deep roots)

James McAnally

December 2021

Jordan Weber. Prototype for poetry vs rhetoric (deep roots), 2021. Image courtesy of the Walker Art Center.

Lowry Bridge sits on circular cement pilings, spanning the Mississippi River near its mouth in North Minneapolis. Two looped arcs lean towards one another, steel cables stretch up criss-crossing the sky like a swish of unsubtle netting. At night, the lighted bridge reflects in the river, forming an oblong hoop. The air looks clear here in the northern sun. Even the shimmering water seems cleaner this close to the mouth before trudging mud for a thousand more miles. The modernized bridge features protected pedestrian pathways and color changing lighting along its 889-foot span. Mature trees line the shore. The infrastructures hum in a seemingly intentional relation to the place. Asthma occurs here at nine times the normal rate. Cancer arrives twice as frequently.1

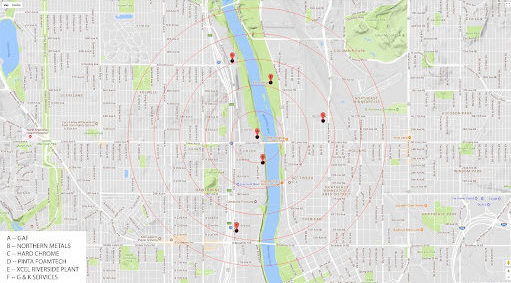

Asphalt – that urban ubiquity – off-gases a tar smell. Oil burn, old, laced with a chemical aftertaste. These scents rend the air along with volatile organic compounds like formaldehyde. The roofing manufacturer GAF sits along the riverfront adjacent to Lowry in the predominantly Black neighborhood of Hawthorne rolling out asphalt shingles in the millions. In recent years, community organizers and neighborhood residents have measured these pollutants as they’ve watched friends and family fall ill, calling on the company to move the factory and to institute more rigorous standards to capture its emissions. The dots mapping GAF and other environmental hotspots along the river radiate out, hotspots inside a target.

Pollution Map of North Minneapolis.

In a formerly vacant lot nearby, other abstracted basketball hoops have arrived into the neighborhood. These structures are functional sculptures that collect rainwater for an urban farm that cultivates plants that resist the pollutants accumulated in the land, in the air, in the breaths and bodies of the residents. The farm, sculptural installation and community space is the capstone of Jordan Weber’s multi-year efforts to engage the endemic impacts of environmental racism in North Minneapolis with a lasting communal platform. For this project, Prototype for poetry vs rhetoric (deep roots), carried out over the past two years as a part of a residency with the Walker Art Center and organized by Nisa Mackie, Weber has convened nonprofit partner Youth Farm, who will maintain and water the garden, as well as an active cohort of architects, neighbors, and Black and Indigenous community leaders to steward the project in its longer life. Around the garden, Weber has added a series of onyx stone sculptures engraved with meditative reminders to Inhale and Exhale, all enlivened by the garden’s relation as a place – for fresh food, for rest, for play, for poetic relations among the land and its inhabitants.

Jordan Weber, 4MX Greenhouse, 2018 (and ongoing). A community greenhouse built on the site of Malcolm X’s birthplace.

Weber’s works have emerged in recent years as a series of expanding prototypes that are sculptural in form but increasingly infrastructural in effect. These functioning gardens, greenhouses, to-scale stoops and reflective hunting blinds-as-barbershop are built to both reorient and remake power in relation to the crises that encircle our time: carceral capitalism, environmental catastrophe, and structural racism, in particular. Weber’s projects have most often flourished in fields and forests, as living (infra)structures in direct relation to the landscapes of the Midwest. Even in early works like American Dreamers (Phase II) (2015), a deconstructed police cruiser filled with soil from Ferguson and invasive plant species, Weber’s work arced toward life and growth, if only metaphorically. As his work has developed, his projects have taken on a more operational scale. The 4MX Greenhouse at the site of Malcolm X’s birthplace in Omaha, Nebraska, was an important moment in this shift, one that counters the deserts of whiteness through the reconstruction of X’s home as a greenhouse – a memorial overfull with life.

Jordan Weber, Obsidian Eagle, 2020. Image courtesy of the Walker Art Center.

Prototype for poetry vs rhetoric (deep roots) (2021), however, is a monumental inflection in Weber’s work as it has followed a steady ascent over the past decade through the Midwestern grassroots from independent spaces like The Luminary, where I first encountered Weber, as well as the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Charlotte Street Foundation and Des Moines Art Center to wider institutional acclaim. Starting with a fellowship with A Blade of Grass and the 4MX Greenhouse, he leaped out from this circulation to the Walker Art Center, a year-long fellowship at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation and the Sam Fox School of Art & Design, and, most recently, a prestigious Creative Capital award and Loeb Fellowship at Harvard University. With this relationship between a community-minded practice and increasingly institutional reception, a question – familiar to the institutionalization of socially-engaged practices over the past few years – opens up around power: how to hold and distribute it.

Despite this heightened visibility, Weber circulates at a time-delay with other Black spatial imaginaries, such as Theaster Gates’s real estate capitalization in Chicago or Rick Lowe’s Project Row Houses in Houston, with his own work more often returning to the earth. This distance from Chicago, say, to Iowa, where Weber has been rooted, manifests in the grasses and soil that sustain the work rather than brick, tar and mortar. Its reclamation ethic is interested in undoing the industrialized terraformed landscapes of the Midwest that ripped up the roots that had previously held the land together, that absorbed flash floods and offered sustenance. These deep roots are among the most endangered ecosystems on earth – in art, as in nature.

What has replaced the tallgrass prairies of the Midwest as one of the most diverse ecologies in North America is a polluted landscape with lead in the collards, raised beds with asphalt separating the plants from the earth, endlessly engineered seeds entrapping the land with patents.2 The roots of this new land can be traced to racial capital, which contains Black, Brown and Indigneous communities within a damaged, dangerous desert. Redlining practices create neighborhoods like Hawthorne in North Minneapolis offering the only affordable land available for these communities adjacent to factories and Superfund sites. Within this polluted landscape, Weber aims at a horizontal prairie ecology, the roots stretching out and down, twisting, creating solidarities that stitch together a kind of kin.

Jordan Weber, American Dreamers (Phase II), 2015. Image courtesy of the artist.

the whiteness

of the desert where I am lost

without imagery or magic

trying to make power out of hatred and destruction

– Audre Lorde, “Power”

The title of the work, Prototype for poetry vs rhetoric (deep roots), is drawn from Audre Lorde’s poem “Power,” which twists its way from a meditation on the efficacy of poetry to a brutal accounting of a police murder and a too-predictable acquittal (and back again). Weber has been intervening in the criminal justice system for years, perhaps most visibly in American Dreamers (Phase II) described above, but also in showing up within protest actions well beyond his artistic practice. In the years after the Ferguson Uprising in St. Louis, Missouri, Weber has been working with civil rights law firm ArchCity Defenders on a series of works in solidarity and collaboration with their #ClosetheWorkhouse campaign to shut down the medium security institution. Starting with a commission for The Luminary and continued in a residency at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation and Washington University’s CRE2, this work attempts to create spaces for formerly incarcerated individuals to breathe freely beyond the institution with meditation gardens and other collaborative projects with farmers and abolitionist organizers alike.

Jordan Weber, Prototype for poetry vs rhetoric (deep roots), Opening 2021. Image courtesy of the artist and Walker Art Center.

Prototype for poetry vs rhetoric (deep roots) is a distinct work aimed at life rather than reform, cultivating healing and repair rather than oriented towards protest. Yet, in true American fashion, as its planned groundbreaking coincided with the simmering uprising in response to George Floyd’s murder just days before in South Minneapolis in June 2020, the criminal injustice system encircled the work. As the project was set to open, contractors refused to deliver materials to the neighborhood, citing safety concerns – an echo of the redlined resources denied over decades in adjacent spaces that capital can abandon and ignore at its convenience. Yet, the project went forward, its own form of resistance. As the cameras and white nationalists descended, as the police cruisers were upended and buildings burned, roots descended too, connected with each other, growing stronger. Invasive species were weeded out of earth that had inherited cancerous VOCs and started the slow process of healing. The plants went in – prairie grasses to hold the ground and dark greens to help sustain neighbors. With Youth Farm, the local nonprofit that will maintain the garden and help redistribute its produce, the prototype grew, and continues to grow, beyond its opening.

And yet. And yet, the ecosystem is still shattered. Asthma is still up. Cancer continues to rapidly multiply. Organizers still attempt to shut down polluters in their backyard, emissions infiltrating the air around. What is it to make power out of the destruction of our institutions, our societal slouching towards carceral capital, out of the catastrophe of climate seeded over centuries? What prototypes are required to resist this desert, to reseed new roots? Audre Lorde sees the danger inherent in power, ending the poem by reflecting on the violence she is also capable of circulating back into the loam of the United States and turning the questions back on her own work:

unless I learn to use

the difference between poetry and rhetoric

my power too will run corrupt

As Weber continues an ascent into institutions and infrastructures that have helped shape a contemporary relation to the landscape, including its monocropped whiteness, Prototype will remain a meditation to return to. How does one make power out of destruction and enter into a relation with power without it undermining the cultivation of new communities and solidarities? The fundamental incompleteness of a prototype, its unending making and activation through planting cycles, water reclamation, and community movement with it, its insistence on learning to use the difference between – poetry and rhetoric, community and institution – is a humble guide to resist capture and run from a corruption of power. A prototype: to root in the land, deeply, to attend to it, turn it over year after year, weed out unworking and invasive arrivals, attending to an incomplete and always expanding root system that at times grows up and out towards the light, at times twists down unseen, or stretches horizontally over and through, symbiotic systems moving through their seasons.

Footnotes

- Steve Brandt, “Researchers find spike in cancer, asthma near Lowry Av. Bridge,” in StarTribune, 26 July 2016, date of access: 29 Nov. 2021, https://tinyurl.com/4mp525w5.

- According to the National Park Service, the tallgrass prairies of the Midwest are “one of the most complicated and diverse ecosystems in the world, surpassed only by the rainforest of Brazil.” See: “A Complex Prairie Ecosystem,” National Park Service, date of access: 30 Nov. 2021, https://tinyurl.com/mr454c34.

James McAnally is the Executive + Artistic Director of Counterpublic 2023. He additionally serves as an editor and co-founder of MARCH: a journal of art & strategy, was the co-founder and director of The Luminary, an expansive platform for art, thought, and action based in St. Louis, MO, and a founding member of Common Field, a national network of independent art spaces and organizers. McAnally has presented exhibitions, texts and lectures at venues such as the Walker Art Center, Kadist Art Foundation, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, The Artist’s Institute and Gwangju Biennale. McAnally’s writing has appeared in publications such as Art in America, Art Journal, Bomb Magazine, Hyperallergic, Terremoto, and he is a recipient of the Creative Capital / Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant for Short-Form Writing.