A Casket for All Seasons

Hande Sever

November 2023

In either 1977 or 1978, we (a group of 35 trans women) brought about a significant disruption at Sansaryan Han. We organized ourselves into a human barricade, confronting the officers and ascending to the uppermost floor near the dome . . . With determination, we questioned the purpose of the locked closets, demanding their contents be revealed by forcing them open. As each door swung ajar, a distressing sight emerged – humans confined within. These individuals were unable to sit or recline, forced to remain standing. Some had endured this plight for weeks, while others had languished for months. They entrusted us with their families’ phone numbers, urging us to contact them and alert them to their confinement within Sansaryan Han. Although their affiliations remained unknown to us – anarchists, communists, or otherwise – we saw them first and foremost as fellow humans, as we ourselves had endured comparable suffering and torture.

—Belgin’s account from Being Queer in the 80s1

Front facade of Sanasaryan Han, 2023.

Since 2018, I have been persistently investigating a singular edifice, Sanasaryan Han, found nestled within Istanbul’s tourist-laden neighborhood of Sirkeci. This inquiry began when I learned that my father was apprehended and confined within its walls in 1977 for being a member of the People’s Liberation Army of Turkey.2 For the past several years, I have been able to gain access to numerous archival documents relating to its construction and have visited the site on multiple occasions. In the following synopsis, I have sought to create a dialogue among memories related to Sanasaryan Han which have not previously been connected, and to question the borders of memory and remembrance by moving through a building’s life in images.

Sanasaryan Han, circa 1990, photographer unknown. Photographic print. Istanbul, SALT Research. AHISTEMIN001.

Despite its nondescript appearance in this photograph from the nineties, Sanasaryan Han serves as a poignant testament to the city’s brutal past. Originally conceived as an inn, this edifice was commissioned by Armenian merchant Mkrtich Sanasarian with the purpose of channeling the building’s earnings toward the education of impoverished Armenian youth in the Ottoman Empire.3 Finished in 1895, the masonry building, designed in the neoclassical style, consists of five floors, including a basement, and a central courtyard adorned with stone cladding. The building stayed operational for twenty years until its fate took a significant turn as it was confiscated and repurposed after the Armenian Genocide.

Archival photograph showing British occupation troops marching in the Tophane district of Istanbul, circa 1920, photographer unknown. Photographic print. Washington DC, Library of Congress. PR06CN087.

After Sanasaryan Han was first confiscated, the building served as the headquarters for the British occupation forces during the armistice period of World War I, and its basement was converted into prison cells during that time. Following the establishment of the Turkish Republic, the edifice underwent a significant transition and became the Istanbul Police Headquarters in 1937.4 Throughout its time as a police headquarters, Sanasaryan Han gained notoriety due to its ominous torture chambers constructed for political prisoners, colloquially referred to as “caskets” due to their upright dimensions measuring 60 centimeters in width, 1.8 meters in height, and 40 centimeters in depth.

Entrance to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, 2022.

The architect behind these caskets was Haluk Nihat Pepeyi, Istanbul’s chief of police, who honed his methods of torture after an official trip to Nazi Germany in 1943. During his visit, Pepeyi toured arms factories and also sought permission to explore the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.5 Notably, Sachsenhausen held mostly political prisoners and queer people throughout World War II. Pepeyi drew inspiration from the torture techniques used in this concentration camp, aspiring to apply them within the confines of Sanasaryan Han. Subsequently, he devised his own method of torment, which involved incorporating bright, spiraling, wired light bulbs into the caskets, effectively disorienting the inmates’ sense of time.

Nâzım Hikmet in the center with Vartan İhmalyan on the left, photographed while in exile in Warsaw, Poland, 1958, photographer unknown. Photographic print. Istanbul, Nazım Hikmet Ran Photo Archive. Courtesy of Nâzım Hikmet Culture and Arts Foundation

During the crackdown on communists in the forties and fifties, which specifically targeted the Communist Party of Turkey (TKP), over 100 individuals endured prolonged interrogations marked by torture. At the hands of a police division known as the “Political Department” or “Communist Desk,” this brutal treatment frequently persisted for months and, in some instances, even years.6 Subsequently, dissident writers, poets, and artists with affiliations to the TKP were added to the list of those confined to caskets and subjected to further torment. Among them were noteworthy figures such as Nâzım Hikmet, Turkish-Armenian writer Vartan İhmalyan, Turkish painter Nuri İyem, and Turkish folk singer Ruhi Su.

In 1945, one of the prisoners, Hasan Basri Alp, lost his life due to torture. The police report claimed that he “sprinted to the rooftop and jumped from the structure.”7 However, this assertion remained unverified, given subsequent accounts that suggested such claims of inmates leaping from windows and rooftops often served as a facade to conceal instances of extrajudicial executions and deaths resulting from torture. In his poem titled “Regarding Newspaper Photographs,” Nâzım Hikmet eloquently portrays this grim reality:

A young soul who couldn’t endure the torture,

Leapt from the third floor of police headquarters.

Meanwhile the chief police officer,

Descending from a plane’s stairs,

Returning from the United States,

Was debating ways to warp prisoners’ perception of time.

As they found contentment,

In administering electrical shocks to inmates.

And they held a conference

On the virtues of our caskets.8

Deniz Gezmiş detained in Sanasaryan Han, 1969, photographed by Erol Olgundemir. Photographic print. Courtesy of Depo Photos

In the lead-up to the 1980 Turkish military coup, a number of prominent leftist revolutionaries, including Deniz Gezmiş and Cihan Alptekin, endured torturous treatment at Sanasaryan Han. However, they were not the sole victims, as Sanasaryan Han also became a focal point for “operations” aimed at trans individuals. This is because the coup government overtly targeted and criminalized both trans people and leftist revolutionaries.9 In the quote at the beginning of this article, a trans woman named Belgin offers a vivid account of the conditions within Sanasaryan Han in an oral history publication produced by the grassroots trans rights organization Siyah Pembe Üçgen in the city of İzmir. Expanding upon the initial quote, she conveys:

They led us to the uppermost floor of the police station, where a colossal door stood. Despite the ongoing denial by the police officers, the truth remains unchanged. Adorning the door’s summit, a placard read, “Within these walls, Allah does not exist and the prophet left for vacation.” I took in those words as I crossed the threshold. Yet, now the police officers contend that such a sign was never present. In this country, whenever claims of nonexistence arise, there is often a concealed truth.10

Sanasaryan Han in Istanbul Sirkeci covered with a construction safety net for renovation, 2022.

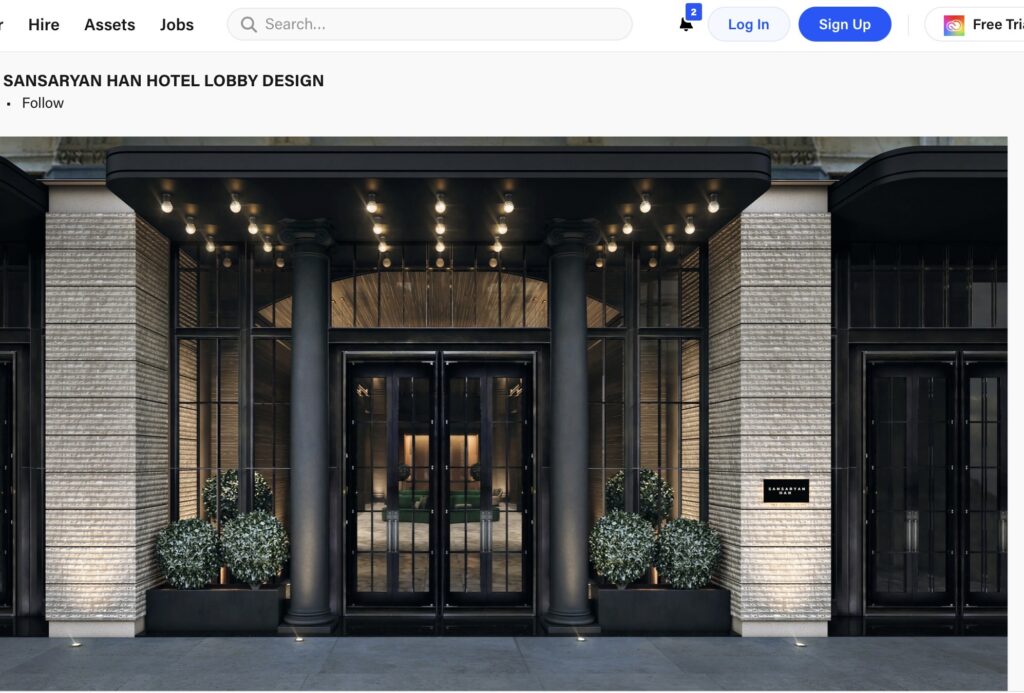

Screenshot of a portfolio on Behance with a proposed design for the renovation of Sanasaryan Han as a luxury hotel, 2023.

Since its confiscation following the Armenian Genocide, the ownership of the building has remained a matter of dispute, with the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople initiating legal proceedings against the Turkish state – a lawsuit that persists to this day.11 Despite this ongoing legal battle, in 2013 the state proceeded to lease the property as a hotel, a move that hinged upon its refurbishment. A construction firm named Özgeylani İnşaat secured the lease for a monthly sum of 235,000 Turkish liras (around $8,500 USD).12 However, first in 2018 and then again in 2022, the Turkish Court of Justice ruled in favor of the Armenian Patriarchate, ordering the building’s restitution.

Banners of the construction firm Erkale İnşaat surrounding Sanasaryan Han, 2023.

Currently, in defiance of the court’s ruling, the building remains under the grip of another construction company, Erikale İnşaat, which is currently overseeing its transformation into a luxury hotel. This echoes a trend observed with the Sultanahmet Prison, now reborn as a Four Seasons Hotel, suggesting a pattern of heritage sites being repurposed as luxury accommodations rather than a reconciliation with their violent pasts. At a time when nationalism and authoritarian politics are on the rise globally, and the crackdown on dissidents, as well as anti-trans and anti-Armenian sentiments, are stronger than ever in Turkey, it is in reconciling and recognizing these memories that still live in the built environment that ground can be created for renewed and unexpected forms of solidarity.

Entrance to Sultanahmet Prison/Four Seasons Luxury Hotel, 2023.

All images courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted.

Footnotes

- Siyah Pembe Üçgen, 80’lerde Lubunya Olmak (İzmir: Global Dialogue, 2012), 72. Translation by the author.

- The People’s Liberation Army of Turkey was a far-left political and military group formed with the aim of liberating all oppressed groups in Turkey. Founded by student revolutionaries Deniz Gezmiş, Hüseyin Inan, and Yusuf Aslan, the organization saw its leaders later executed by the 1971 Turkish Military regime.

- Zakarya Mildaboğlu, “Sanasaryan Varjaran’ın Gasp Edilen Yetim Hakkı,” Agos, July 14, 2014, link.

- Rıfat N. Bali, Tabutluklar, Sansaryan Han ve İki Polis Memuru (Istanbul: Libra, 2011), 23–47.

- Bali, Tabutluklar, 68–74.

- Bali, Tabutluklar, 103.

- Vedat Türkali, Güven (Istanbul: Ayrıntı Yayınları, 1999). Translation by the author.

- âzım Hikmet, “Gazete Fotoğrafları Üstüne,” in Nazım Hikmet, Son şiirleri (1959–1963), ed. Güven Turan (Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2013), 17. Translation by the author.

- Üçgen, 80’lerde Lubunya Olmak, 11–21.

- Üçgen, 80’lerde Lubunya Olmak, 64.

- Mildaboğlu, “Sanasaryan Varjaran’ın Gasp Edilen Yetim Hakkı.”

- Nevzat Onaran, “Erzurum Kongresi, Ermeni Sanasaryan Okulu’nda yapıldı,” Gazete Duvar, July 23, 2022, https://www.gazeteduvar.com.tr/erzurum-kongresi-ermeni-sanasaryan-okulunda-yapildi-haber-1574351.

Hande Sever is a Los Angeles-based artist and author from Istanbul, Turkey. Her transdisciplinary and concept-driven practice combines lens-based image-making with organic materials to unearth the shared materiality underpinning colonial histories. Archival research is the main drive of her practice as she excavates lost texts and distant images to bring attention to events erased from the collective consciousness and recontextualizes transnational instances of mass violence and political struggle in the process. Her research-based works have been presented at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, UK; MAK Museum Vienna, Austria; CICA Museum Seoul, South Korea; Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, IL; A.I.R. Gallery, New York; BOX Gallery, Los Angeles, CA; and other international venues.