A Memorial for the New Economy

Chinar Shah

December 2023

Chinar Shah, A Memorial for the New Economy (Bangalore, India: Reliable Copy, 2019).

On November 8, 2016, the Government of India demonetized all circulating 500 and 1000 rupee banknotes without warning. This move suddenly invalidated these notes, rendering them unusable in exchange for any goods or services. Instantly, India’s heavily cash-dependent economy found itself in an unstable position. In the days following this announcement, it was apparent that there were no systems in place to handle the ensuing chaos and confusion. With a significant portion of the population lacking access to digital banking, long queues formed outside banks as people sought to withdraw their funds. Panic quickly set in, exacerbated by the rapid spread of rumors. Overwhelmed bank staff found themselves ill-prepared to handle the deluge of customers, while the banks were not adequately stocked with the new currency, as it had not yet been fully printed or distributed across the national banking network.

Among numerous rationales offered by the government, the primary motivation cited was to restrict the flow of illicit funds often referred to as black money. While the government had assured the public that essential services would not be disrupted, instances arose where hospitals refused to admit patients and people faced difficulties purchasing food and medicine. Amid the frenzy of the affluent strategizing how to handle their undisclosed wealth, many others believed they had lost their life savings. It took several days to reassure a large part of the population that their money remained secure. These information gaps, coupled with the lack of infrastructure, a hasty approach that failed to consider short-term consequences, and the acute shortage of new currency in circulation, created an atmosphere of fear and panic.

In the months following this announcement, the toll became tragically apparent with over one hundred individuals losing their lives due to various causes. For instance, numerous reports surfaced of individuals collapsing or suffering heart attacks while waiting outside banks for days. Even a bank manager fell victim to a heart attack, having worked under immensely stressful conditions for three consecutive days. Some individuals reportedly succumbed to shock upon realizing that their money had lost its value. Tragically, suicides were also documented during this period, with many attributed to the shock of the situation and others to the pressures of being unable to fulfill financial responsibilities.

This action by the ruling party, one steeped in divisive nationalist policies, was sold to the people under the rhetoric of a “greater good.” Human suffering was framed as a virtue – a subjectivity forced onto the larger population. There is still no concrete evidence of this demonetization’s positive impact on the economy, nor has it been effective in curbing the circulation of black money. What we are left with, instead, is a denial of the violence of demonetization and, by extension, the denial of these consequential deaths. There has been neither a collective acknowledgment of this loss of life nor any form of mourning.

These lives that went largely ungrieved were also stripped of their personal histories. We know nothing about them except for a few names that appeared in passing in some newspapers. There were no floods, no famines, no riots, no murders – nothing tangible to have caused these deaths. Instead, only an abstract event acting upon an entity equally abstract – the economy. Within a scenario where these deaths were represented in the abstract, the question of whether they really even happened is constantly encountered.

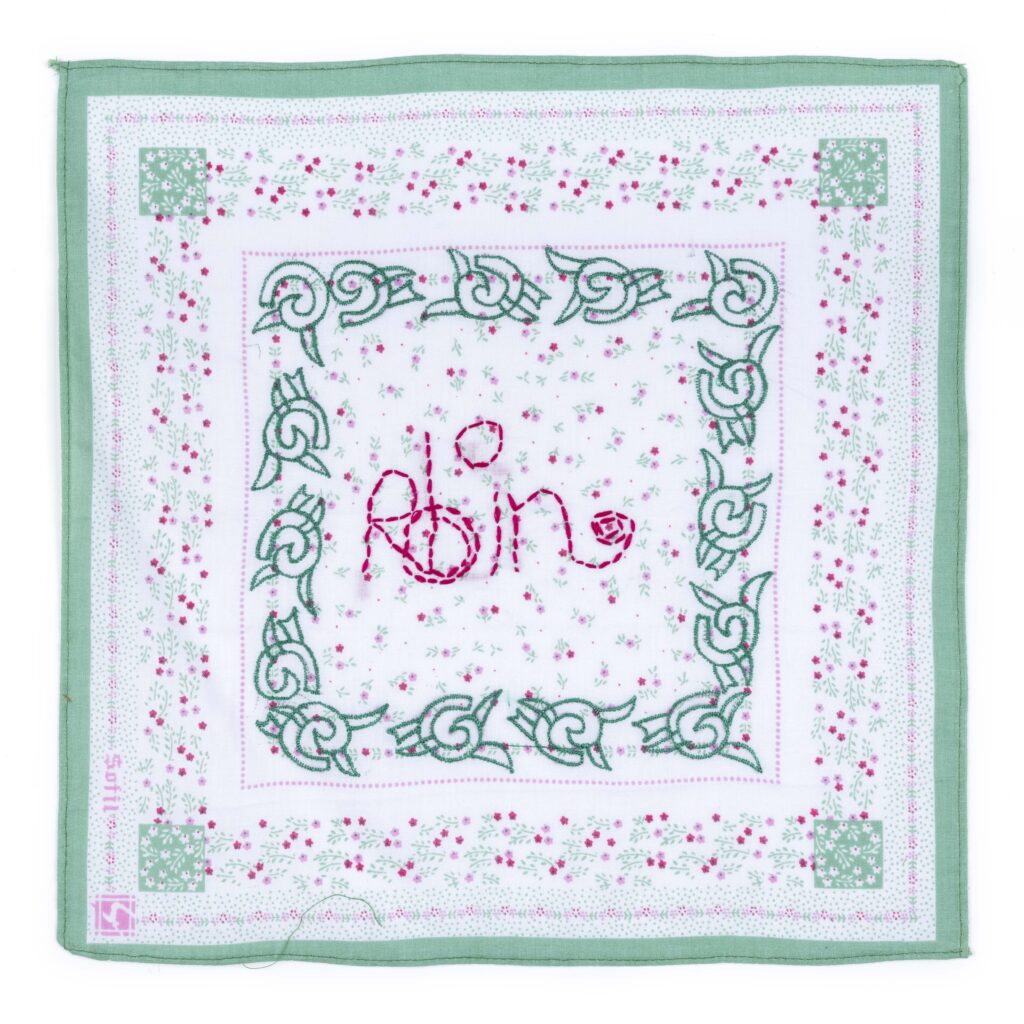

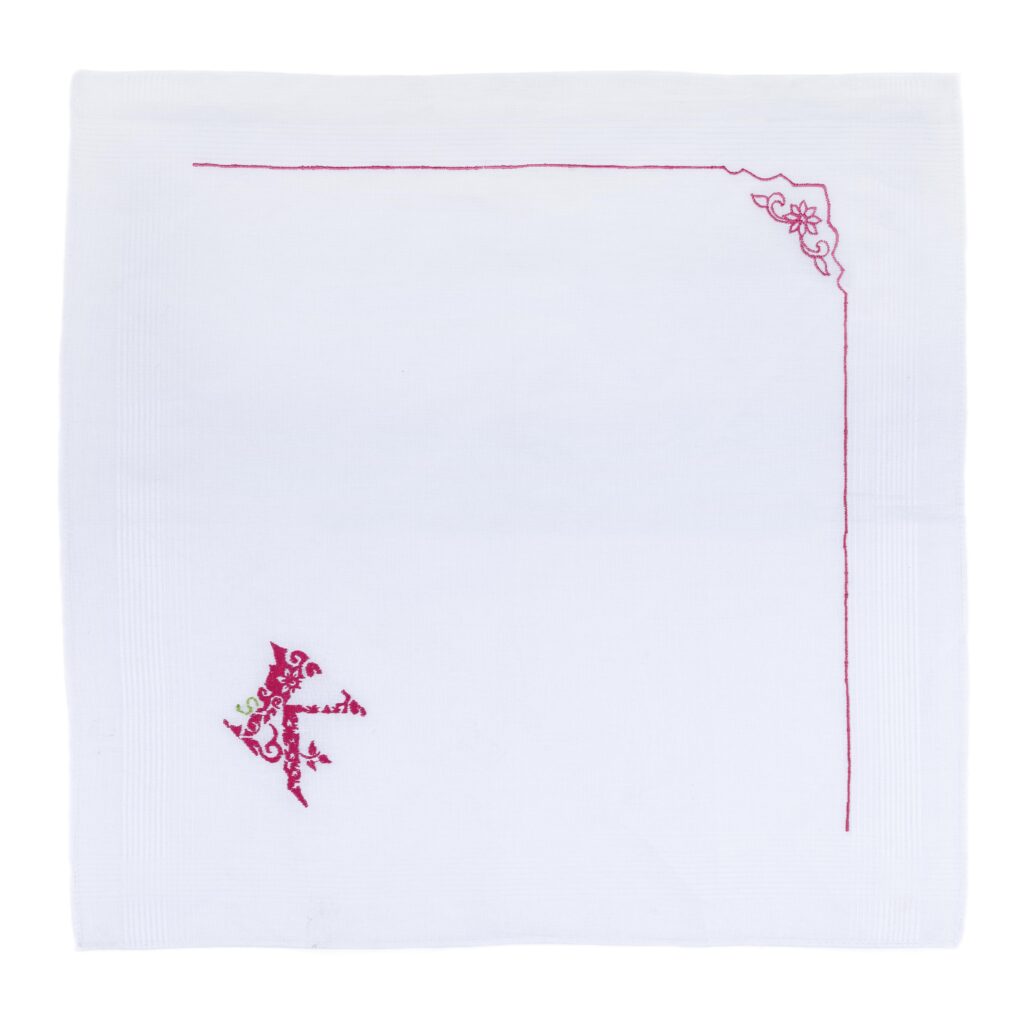

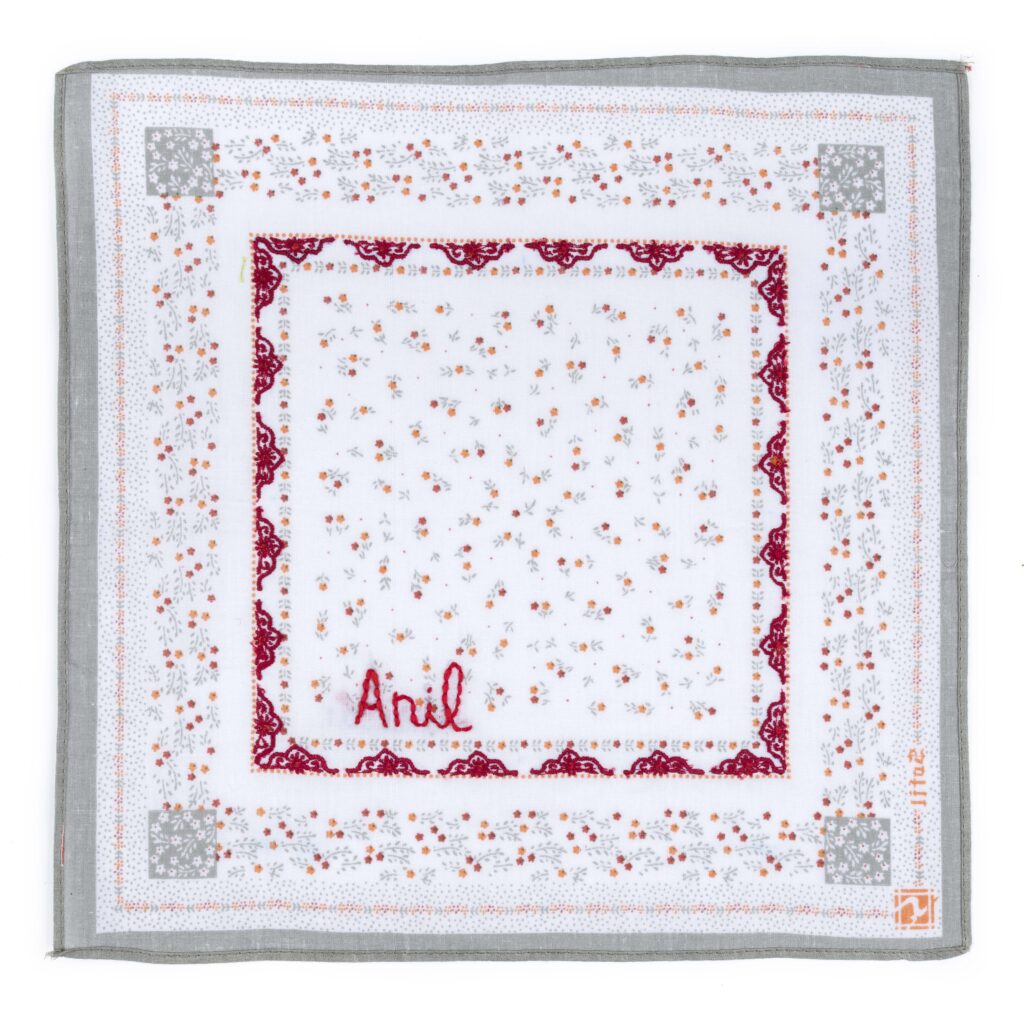

As a way of memorializing the dead, I began embroidering the names of each individual reported to have died as a consequence of demonetization on handkerchiefs sourced from local markets. A handkerchief is a personal token, often gifted or safely accounted for with initials. In addition to the names, I embroidered various floral motifs found on the now-invalid banknotes. The choice of the handkerchief and its material history is both intimate and fragile. However, the handkerchiefs, as singular, precious objects, became a limiting factor in the circulation and dissemination of the work. Thus, this body of work became a collection of photographs of each handkerchief, then made freely available as a digital publication of high-resolution downloadable files. The resulting publication, A Memorial for the New Economy, functions as a public document that registers not only the event of demonetization but also its aftermath. In this way, A Memorial for the New Economy proposes a memorial that is neither a grand proclamation nor a fixed monument, but instead one that is dependent on systems of distribution, access, and exchange.

As a photographer, I have often faced situations where the multiplicity of the past, the present, and my presence influence the images I am able to take. Often, people would pose for a photograph informed not only by violent memories of an event but also by the visual history of that event – how the media represented it, what images, expressions, and moods carried over time. For example, I was on a documentary shoot in 2012 working with survivors of the communal riots in Gujarat when I realized that people would pose in a certain manner, seemingly trained by the pervasive visual imagery that existed around that trauma. In this way, the photographs themselves can become sources of trauma, perpetuating distress, particularly due to the limited control one has over the circulation of images.

In my practice, I try to respond to events, stories, narratives, and the history of photography in one breath. By inserting myself into the photographs through formal, aesthetic, and visual choices, I attempt to hold multiple points of reference that are not only derived from the stories I work with but also from the histories and memories of the forms and materials of photography as a medium. It is evident in this process that memory is not only structurally multidirectional but that “each articulation of the past processes that multidirectionality differently.”1

A Memorial for the New Economy and its form speaks to my practice of being a documentary photographer. Handkerchiefs, embodying personalization and fragility, stand in contrast to the documentary evidence of photographs. This dynamic underscores the complex interplay between truth and memory, encapsulating the uneasy relationship between these two elements. While this creates the possibility of mourning – and, by extension, a commemoration – the work is not a memorial in itself, but is always in the process of memorializing as it circulates inexpensively while simultaneously existing in multiple places. In other words, this memorial unfolds as people join the process of dissemination through downloading, sharing, and printing. In this sense, A Memorial for the New Economy is a memorial in the making, open to different possibilities dependent on circulation.

A Memorial for the New Economy is available for download from Reliable Copy in low and high resolution files and licensed under copyleft.

Footnotes

Chinar Shah is an artist based in Bangalore. She is interested in documentary practices and uses her screen as a site to produce, circulate, and negotiate images. Shah is the founder of Home Sweet Home, an exhibition series and research platform focusing on self-organized, independent arts initiatives in India. She co-edited Photography in India: From Archives to Contemporary Practices, published by Bloomsbury, London, 2018.