Art After the Future

James McAnally and Andrea Steves

May 2020

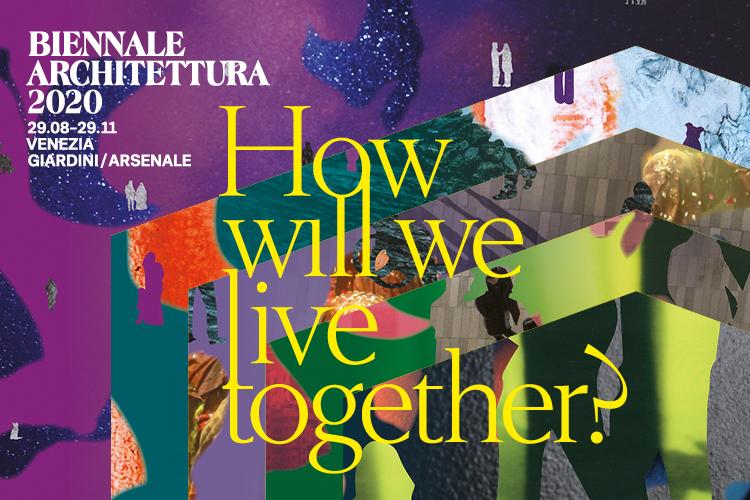

On March 4th, 2020, the Venice Architecture Biennale sent a mass email announcing the postponement of its intended opening date until the fall. Followed by a second letter on May 18th, 2020 delaying the exhibition until 2021, these deferral letters are the perfect artifact of the art world we knew before. Inadvertently cataloguing the acute derangement of the contemporary art world, the letters trace a persistent belief that both art and the world will be able to return more or less unchanged. They assume an after in which the Collateral Event1 of COVID-19 will be footnoted as a temporary inconvenience to be conceptually recuperated and otherwise overcome. Titled “How Will We Live Together?,” the exhibition’s theme and it’s too-timely deferral arrived at a moment in which perhaps the more proper question is: Will We Live?

This early postponement was an opening salvo for an indefinite and unprecedented sequence of closures, cancellations, delays, transitions, translations, and digitizations of presence that have marked the art world since. In subsequent weeks, most of the world’s museums went dark and Zoom became the primary medium of social persistence. Artists stayed home, submitted applications for emergency relief funding, and filed for unemployment. They made zines, made sourdough, made performances for Twitch, publications for emails, paintings for eventual outside walls, masks for themselves and mass deployment. The museums scrambled to digitize everything, started reading groups, activated the archives, led remote walkthroughs for maybe no one, wrote us all emails about These Uncertain Times and This Moment; about how Now More Than Ever Art will help lead us through. Art school went on, sort of. Degrees and debt were extended. Learning, in theory, occurred.

Wait, why are we using past tense? When is our present? Where is our future?

We write from within an ongoing all-world event. We began this essay when Andrea arrived in St. Louis for a residency at The Luminary (where James is the director) just as the Venice Architecture Biennale was first postponed in early March 2020. As long-time collaborators, we met at the train station, exchanged hugs, and headed to an event in St. Louis where dozens of people crammed into a classroom, chanted Assata and ate from shared pizza boxes while organizing to shut down the city’s medium security prison. That night, we caught up over drinks and tacos at a busy bar, easy among strangers. We shared some early concerns about coronavirus, playing out worst case scenarios that felt like science fiction. Within a week, our easy proximity gave way to cloistered communications from a few blocks away as distancing procedures set the pace of our days. This text began as a conversation, a shared air, and then moved to mediated sessions from one iMessage to another, from one bunker to another—much in the way that it circulates now between all too many screens.

Within the acute body of the art world, it is increasingly clear that beyond and around the coronavirus the market collapse and global uncertainty threatens an unprecedented slowdown—the proper economic concept for our confused time. Many of the impacts of this pandemic are unthinkable: the sudden global isolation into quarantine, the sheer volume of lost lives, lost time, losses of all kinds. Yet, within the art field, this moment has revealed structural fault lines that have been present for years, underlying conditions that require a rethinking of its core assumptions of normalcy and what worlds to which we will be able to return. As we enter a period of uneven reopenings in the coming weeks and months, into what future are we entering, and which art worlds will persist?

***

In a much-circulated speculation, Americans for the Arts projected that perhaps one third of the museums that temporarily suspend operations during the coronavirus outbreak will never reopen. Another major funder reportedly stated that, given the widespread collapse likely coming within the field, they were waiting to see which institutions would survive before infusing more cash. In other words, they would be there to lend support, but only to the survivors on the other side of this extinction event. Regardless of any stimulus offered now or later, thousands of museums may not reopen. Maybe even more than predicted. Closures will be delayed six, twelve, twenty-four months, as admissions disappear, contributors divert funds to other relief efforts, hotel tax funds dry up, and corporate giving and state support recedes.

Many Cities, States and Universities in the United States and elsewhere are already entering austerity procedures, shutting down Arts and Culture Departments and shifting funds to make up for shortfalls in other areas like healthcare and unemployment.2 Austerity is increasingly becoming a long-lasting assumption. In a well-researched article in The Art Newspaper, the president of the International Council of Museums (Icom), Suay Aksoy, warned, “This crisis has put numerous cultural institutions around the world on the verge of economic collapse,” and reports are dire everywhere. The pandemic’s impact is uniquely cutting across many sectors, forcing shortfalls in earned income as attendance plummets and tourism comes to a complete stop, impacting philanthropy of all kinds, and initiating cuts on a State level in most nations.

Even with emergency stabilization, hundreds of already overleveraged and underfunded organizations are teetering at best, resisting their own impossibility. However, these closures will inevitably affect the most fragile first: un-institutions, artist-run and DIY spaces running on volunteer staff and side gigs, rural organizations, and QTPOC+ run spaces already barely able to survive. In other words, survival will be unevenly distributed, as always.

Those with enough cash reserves and donor connections will sustain, for a time, absorbing a disproportionate share of bailout funds while rarely reaching down to support those more fragile (in art as everywhere), but even reserves can only go so far, as is already becoming clear. The existence of endowments and government funding to sustain institutions in the midst of a crisis is a myth that disappears as soon as austerity is socially acceptable. The museum director retains their full salary as the hundreds below them are on hold with the unemployment helpline.3 The building project goes on (or gets torn down), even as there is no one to enter the galleries. The losses aren’t indexed by the virus, but by the ways the virus manifests the inequities and brutalities of the systems we’ve enabled to exist. In this reordering of resources, which continues to play out on a global scale, a rearticulation of demands for other art worlds is now more urgent than ever.

Amidst these dramatic impacts of an economic slowdown, what we are not seeing is a corresponding personal or institutional slowdown. Instead, many artists and organizations are in the throes of an exhausting pivot to overproduction, including a scramble to new platforms. The current explosion of online content in our field feels frantic. In an opportunistic rush to capture quarantined attention spans, platforms are flooded with new chances to log on, participate, passively consume, and, of course, purchase. Most institutions, which are extensions of our anxious selves, only know how to just keep going. The organizational machine keeps making its way.

The silence, the strike or stoppage too closely reveals oneself to be non-essential—for a budget, to be sure, but also often for a public. Art institutions are built on perpetual motion. The inertia of activity always assumes a next: the next exhibition is announced as the previous one opens, the grant deliverables are always eighteen months out. Now, the programs are rarely cancelled, just shifted online, or indefinitely deferred. These crises at the institutional level inevitably fall on artists, who are asked to show up and reorient their work for a changed world no matter how their bodies or minds are managing. The moving assembly line of deadlines and mechanics of alienated hyper-productivity are at odds with pause, silence—or illness.

From within this truly exceptional moment, we are asking: can we not? Within a rupture in which the overwhelming waves of illness, of stoppage, of death is palpable, can we embrace silence for a moment? The rush to produce refuses the space to reflect on possibilities. Can we step back and witness the vectors of force that keep us in perpetual motion: the pressures from above and outside to perform, overproduce, and appear essential?

Another art world is inevitable. Which art worlds will emerge is not.

COVID-19 is a serial link in a concatenated crisis of which any number of viruses could stand in as some shadow line of no return. These conditions, though heightened into a frenzy as COVID-19 has quickly spread globally across borders and bodies and markets and imaginaries, are not new. From the crisis of capitalism to its resultant climate disaster, any assumptions about how life and art go on a fixed timeline with infinite futures under continuous inflation should have been questioned for decades. If anything, the rapid insertion of quarantines, deferrals, cancellations and generalized shutdowns into our previously assumed near futures helps clarify where we actually were—and still are.

In this suspended state, it is clear how precarious any idea of the future is, as well as how much of our work’s meaning is dependent on some future that finally justifies it. The speculative structures of contemporary art and its institutions are a pinnacle of forever futuring that take the most fragile of forms, gestures, and ephemeral marks and attempt to extend them for posterity. This future is embedded into our economy, our institutions and societies, our daily rituals and artistic practices. Institutionalization of future economic opportunities and risks through debt structures, like the student loan pyramid or the many forms of market production, competition, and scarcity, is fundamental to our orientation towards work and reward: a capitalist imaginary foundationally about the future and the possibility of growth.

The infrastructures of the art world require the world to continue as it has been, supported by extreme income inequality and aspirational spectacles for prestige patronage, subsidized by artists willing to take on unsustainable debt to enter graduate programs, and enabled by assumptions of freedom of motion and frictionless exchange. Nowhere is this more clear than in the art world’s dependence on overwhelming resource burns: infinite oil for sprinter van shipments and freights and flights, coal for the climate controlled crates and precise air control in the museum, relentless data kept in cold server warehouses, Frigidaires the size of five football fields chilling our iClouds out in the desert.

How long are we keeping things locked in bunkers and for whom? What are we willing to burn to preserve these conditions? Coal and oil, of course, but what about its after-effects? The Australian bush, old growth forests, our backyards, an eventual future? The assumption of permanence actually creates the conditions for collapse. It seems cruel to single out individual institutions and artworks as not worth saving, yet simple to assess the entire system as unsustainable. We are living in the tension between impossible decisions. Haunting the edges of the art world’s obsession with futurity is the reality that this perceived future no longer exists.

What, instead, is an art that embraces no future? How does the understanding of the creation, circulation, and care of artwork, and support of the individuals, collectives and institutions that make up the art world shift when conceptions of deferred worth are removed? Certainly, artists and the infrastructures of art would have to account for the carbon footprint for all of the making, shipping, preserving, and flying that has defined the contemporary art world. Endowments and cash reserves would be suddenly loosened to support the thousands of already suffering fired and furloughed workers. Adjustments for accessibilities for immuno-compromised and disabled participants and audiences finally accelerated in this time would be made permanent.4 Artistic platforms would embrace slowdowns and refusals as form, and differing abilities were assumed at all times and spaces prioritize many other forms of expression and experience.

Some of these particular pivots precede the COVID-19 pandemic, and many have been working towards this groundshift. Numerous artists, curators, and organizations have been orienting to a more holistic relationship with the environment, the land, and the tentative commons we already inhabit to embrace this changed horizon in which no future can be assumed.5

To work amidst and beyond the virus is to embrace an art with no future, an art of the now.

Art after the future remains an open question —and our time requires a response.

When I wake up, where should my body be?

“If I survive, it is only because my life is nothing without the life that exceeds me, that refers to some indexical you, without whom I cannot be.” (Judith Butler, Frames of War6)

Coronavirus, perhaps like good art or film or fiction, has done incredible work on the collective imagination, and is rewiring our conception of what is possible. The acceptance of this rapidly shifting world requires us to process a lot of grief. Amidst the grief, there seems to be a new openness to change, and a renewed urgency to remake our systems and relationships to better care for people and the ecosystems we inhabit. What are our infrastructures and institutions capable of caring for this grief while creating space for communal mourning and communal meaning? Can we take time to feel our losses? For now, every day, we are asking simple questions: When we wake up, where should our bodies be? What do we owe each other just for surviving? How are we caring for one another through our own fragility?

What COVID-19 has urgently exposed is our interconnectedness—the sinuous bonds that keep us alive and truly living. This text has many we’s. It also carries interrelated I’s and you’s without whom we cannot continue.7 Just as the virus quickly became borderless and our social bodies were suddenly seen to be porous, both illness and recovery are intimately intertwined—community and immunity returning to their joint root. As the art world emerges from this restless slowdown, can it begin to operate out of the mutuality necessary in this moment?

Art after the future starts to see the world as it is: a fragile, contingent ecosystem in which we are never singular. This un-futured art understands that one’s survival is not in spite of another but with one another. How artists and arts organizations are reorienting now offers some grasp on what will be needed not just now, but what will be needed next. Care collectives, rent strikes, and coalitions of all kinds will be required, as well as an insistence on structural shifts for how work is funded, circulated and shared. The mutual aid and direct support for artists and vulnerable organizations arising now will need to be normalized by grantors, foundations, and the public as immanent life is prioritized. As the social body remains ill and unworkable, artists will need to embrace inoperability. Not-working for once. What work does emerge out of this time will need to not just be conceptually responsive, but materially and structurally responsive to a changed world.

After the reserves and emergency funds are gone, art institutions will need to embrace nestings within one another, and other collective forms of support such as shared infrastructure, space, and staff. Any ethical nonprofit attempting to sustain through this time will need to merge and morph into unfamiliar forms both within and beyond art, perhaps adapting strategies from public spaces like libraries to provide more services and shelter, absorbing more fragile organizations and artistic practices within one another, or abandoning their buildings in favor of grafted publics and partnerships. These recombinations may be necessary practically as funding dissipates, but also represent a moral position of taking up less space in the world: less physical space, fewer resources, reduced carbon consumption, but also making way for other voices to emerge as old forms necessarily change.

Within the unavoidable closures to come (and those already here) how will we embrace ethical endings that seed other futures through the redistribution of not just money, but space, equipment and expertise? Who are the institutional death doulas ready to guide graceful and inevitable exits, to preserve these fragile histories?8 As we take a step (and then the next), as we allocate our time, attention, stimulus checks, ourselves to the tasks on their way we must also ask: What forms of slowness or non-functioning should we preserve from this time? What do we learn from our own sudden emptiness? Inertness? Alertness to our limits? What institutions are worth supporting? What practices are worth preserving? What work is worth making?

We are loosened from time right now in the Great Deferral of 2020. As artists and arts institutions, we can rush in to fill the silence and occupy the time as we are trained to do from decades of over-production. Or, we can let some candles gutter, the fluorescents flicker, and go out. We can let artworks have life cycles, bodied like we are. We can let institutions age. We can take care of the lives they lead, serve as nurses in their illness, as caretakers in a plague. We can make work out of what is at hand. We can say no when our bodies need to. We can say sorry to the earth and each other. We can make space for loss and grief. We can continue to learn from contingency, fragility, slowness and impermanence. We don’t assume a future, but still we support one another today, and the next day, and the next, knowing that our survival is connected in a commons we already inhabit. This is how we will continue to live—together.

Footnotes

- In its second deferral letter, the Biennale framed COVID as a “Collateral Event” forcing its postponement. The authors have initiated an active commentary on the Biennale’s deferrals in an open editable document here.

- Philadelphia’s zeroed budget for the arts has been the most circulated example, but similar measures are either already determined or on their way in cities such as Kansas City, Portland, OR and many more. Australia recently eliminated its Arts & Culture Department entirely on a federal level.

- This essay, though largely New York-centric, offers a critical overview of the layoffs and furloughs disproportionate impacts on part-time and already vulnerable staff: https://www.ssense.com/en-us/editorial/culture/the-museum-does-not-exist

- Though the rapid pivot of programs to digital spheres from one angle reveals a tendency towards overwork and refusal of silence, as discussed above, this pivot has likewise led to changes in accessibility called for by disability activists for years, including digital exhibition and program viewings, captioned content and alt-text gaining substantive support. We hope these changes will remain permanent in the future.

- More artists and organizations have been doing this work urgently over the past few years than can be listed here, but it is worth noting a few we are in dialogue with in our own spheres: Casco: Working for the Commons has been drafting a Climate Justice code for art institutions. Collectives like The Canaries, What Would an HIV Doula Do?, Feminist Health Care Collective, and Power Makes Us Sick have been organizing care networks and interrogating institutions as to their permeability to immuno-comprimised participants and individuals with varying levels of ability for years. Shannon Stratton has proposed a biennial exhibition concept whose mission is to address curation amidst climate crisis.

- Butler’s full text here is important in our discussion of life, loss and survival across singularities with complex and, at times, antagonistic relations: “If I seek to preserve your life, it is not only because I seek to preserve my own, but because who “I” am is nothing without your life, and life itself has to be rethought as this complex, passionate, antagonistic, and necessary set of relations to others. I may lose this “you” and any number of particular others, and I may well survive those losses. But that can happen only if I do not lose the possibility of any “you” at all. If I survive, it is only because my life is nothing without the life that exceeds me, that refers to some indexical you, without whom I cannot be.” Excerpt From: Judith Butler. “Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable?.” Verso p145/Ebook edition

- The “we’s” suggested throughout include the authors, Andrea Steves and James McAnally, as well as at times suggesting other solidarities and sets of relations within and beyond the at world. Many other people have shaped this text in conversation, including Laressa Dickey and Ali Gharavi, who were in residence at The Luminary as the text began, as well as Chloë Bass, Rose Linke, Timothy Furstnau, Sarrita Hunn, Gavin Kroeber and others.

- The phrase “institutional death doula” came in conversation with Gavin Kroeber in a series of impromptu Zoom calls in and around the 2020 Common Field Convening, and was adapted from numerous conversations and thinking around the concept with Betsy Brandt and Brea Youngblood. Taken from practices of hospice, hospitality and the birth and life cycle requiring particular kinds of care, an institutional death doula may be viewed as a suggestive figure or community that guides ethical closures and transition of organizational form.

James McAnally is the Executive + Artistic Director of Counterpublic 2023. He additionally serves as an editor and co-founder of MARCH: a journal of art & strategy, was the co-founder and director of The Luminary, an expansive platform for art, thought, and action based in St. Louis, MO, and a founding member of Common Field, a national network of independent art spaces and organizers. McAnally has presented exhibitions, texts and lectures at venues such as the Walker Art Center, Kadist Art Foundation, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, The Artist’s Institute and Gwangju Biennale. McAnally’s writing has appeared in publications such as Art in America, Art Journal, Bomb Magazine, Hyperallergic, Terremoto, and he is a recipient of the Creative Capital / Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant for Short-Form Writing.

Andrea Steves is an artist, curator, researcher, and organizer currently based between New York and Vienna, Austria. Her recent projects deal with museums and public history, monuments and memorials, and the complex legacies of the Cold War. Andrea also works in the collective FICTILIS and is co-founder of the Museum of Capitalism. She is currently a visiting scholar at the Center For Capitalism Studies at The New School.