at the kitchen table (adjust as per taste)

Arushi Vats

September 2021

In this interview with Sarasija Subramanian and Nihaal Faizal of Reliable Copy, Arushi Vats discusses their forthcoming exhibition at the kitchen table (September 17 – October 5) at 1Shanthiroad Studio/Gallery, Bangalore, India.

at the kitchen table is imagined as a travelling, multi-part exhibition that will expand through its responses to the contexts, sites, and venues of its various iterations, including those of an eventual publication. It is conceptualized and curated by Reliable Copy, a publishing and curatorial practice dedicated to the realization and circulation of works, projects, and writing by, and around artists, founded in Bangalore, India in 2018.

“Art can be like a recipe: One part Levi-Strauss, two teaspoons Merleau-Ponty, one cup Wittgenstein, blend with Saussure till smooth.” –John Baldessari1

Arushi Vats: Thanks for sharing that quote, Nihaal. I do have questions about the recipe as a form, but the first thing I want to ask you both about is this term ‘stand-in’ that recurs in our conversations around the exhibition – the stand-in document, the stand-in presentation – and what this sort of ‘standing-in’ implies. There’s a sense of referentiality built into the idea of the whole at the kitchen table exhibition. Where does that come from? And what is it that you mean exactly when you talk about this gesture of standing-in?

Sarasija Subramanian: I think there’s a lot to unpack there, but to lay the ground perhaps we can tell you a bit about how we began this project. It started with us working on The 1Shanthiroad Cookbook with support from a research grant from India Foundation for the Arts. Before we reached a point where we wanted to look at all of this curatorially, we were simply engaging with 1Shanthiroad (Bangalore’s longest running non-profit arts space and residency) as a community where the kitchen plays a really important role. Knowing that we were putting together a cookbook around this space, we began to collect references that could help us with this project. It was then that this collected material began taking on a life of its own, leading us towards wanting to make it public in some way. At first we were only looking at cookbooks; the artworks and artistic practices came later. Nihaal?

Nihaal Faizal: The idea of the stand-in came from our engagement with a wide variety of documents across this research process, and from understanding how far we could stretch the concept of a recipe or a cookbook. In a way, the cookbook as a form becomes a stand-in for quite a lot of things, whether as a novel in the case of Esther David’s Book of Rachel or a manifesto in the case of F.T. Marinetti’s The Futurist Cookbook. As this ‘standing-in’ of form became foregrounded, we began to think of artworks as similarly framed or bound by formal and commercial categories within which they function and are evaluated. These categories have become especially homogenized as our encounter with most artworks becomes mediated through the possibilities of distribution and publicity – that is, in arriving to us as a photograph, as a press release, a social media post, or in a catalogue. However, this shape-shifting mediated form does open up a lot of possibilities for access, for sharing works across wide distances, and for communicating a range of strategies with regards to artistic production, all things that we are hoping to do with this exhibition.

AV: I was just thinking about this point: the different mediated forms in which we receive artworks and the medium of the cookbook. ‘Food media’ adopts a range of formats such as printed books, radio and television programming, food journalism and food criticism, and food blogs, which supersede the material limits of the food. In some ways, the document(-ation) is a companion – or sometimes superior – to the dish, much like what you discuss about artworks.

SS: With regards to what we are bringing together, it is not food at all or even art, but the methods, platforms, and media in which these subjects are discussed, shared, and presented.

NF: In reading so many cookbooks, what really happened was a suspicion related to the form. It became clear that it no longer had to be approached just one way.

SS: Of course, there are also books presented in the exhibition that can be considered traditional in the way that they adhere to the rules of a form, such as in the case of Samaithu Paar by S. Meenakshi Ammal (although when it was published in 1951 it was branching out to a genre that was not commercially published before in India). This was a book that I grew used to seeing in every relative’s kitchen (and later mine) since I was very young, and this was one of our first references because we weren’t originally looking within art history as such, but at community and family cookbooks. Samaithu Paar is almost like a family cookbook written for the author’s extended relatives, and Ammal writes all of the recipes with as much love and detail as possible, allowing the community to continue the process of cooking. Because of this, it’s filled with small details, tricks, and hints, and addresses the reader in a very familiar way. Another book in the show is Mrinalini Bordwekar’s Path Pani, which is not a commercially published book, but one printed in a small run and intended to be gifted to the author’s friends and family.

While both books share a similar purpose for writing recipes, both have had very different legacies in terms of publishing and distribution. Samaithu Paar was translated into many languages, is still in print, and has travelled the world, whereas Path Pani is a very privately shared book with a print run of about 200 copies. There is also Five Morsels of Love by Archana Pidathala, in which the author collects her family’s Andhra recipes, which is a more recent introduction to the legacy of community cookbooks based on family recipes that began with Samaithu Paar.

NF: So, while these books, and many others, belong to a single genre and category (the cookbook), when expanded, this genre can also be a means of holding very different content, as well as intentions. An example is Leone Contini’s Ricettario Immaginato, which is a republished copy of his great-granduncle’s journals from his time in prison after the Battle of Caporetto. In these journals, his uncle Giosuè notes down recipes shared between inmates for the food they desired and dreamt of – their imagined menu. On the other hand, there is the Ni’matnama Manuscript, which is a historical document from the Mughal period in India, of recipes from that culinary culture and time.

Apart from these books, the artworks presented in this exhibition are brought in through a range of documentary or supplementary material and are looked at as existing in very different ways from their usual standing as artworks. I suppose this is the ‘stand-in,’ where the work itself remains absent but is still hinted at, evoked, or described through another referential document. While this is a conceptual decision, perhaps it is also important to state that it was one informed by the very real contingencies to do with our budget and the surrounding pandemic, where we could neither afford nor practically pull off shipping works from all over the world. This limitation has shaped the show in more ways than one and has led to a realization of what David Robbins, one of the participating artists in the show, says in his book Concrete Comedy: “An idea is never contained by a form but only resides there temporarily.”

SS: Initially, we were looking at this as a way of representing works that already exist through secondary or parallel material, but this premise got shaken up completely in our conversations with the artists. Now every contribution to the show has taken on a life of its own. I think this really expanded our idea of what the document is or is meant to do – it’s no longer secondary in any way. This development began early on in our discussions with Lantian Xie, who was the first artist we spoke to regarding this project, who completely rejected our premise and yet found it relevant enough to generate something within its framework. Nihaal, do you want to talk about this work?

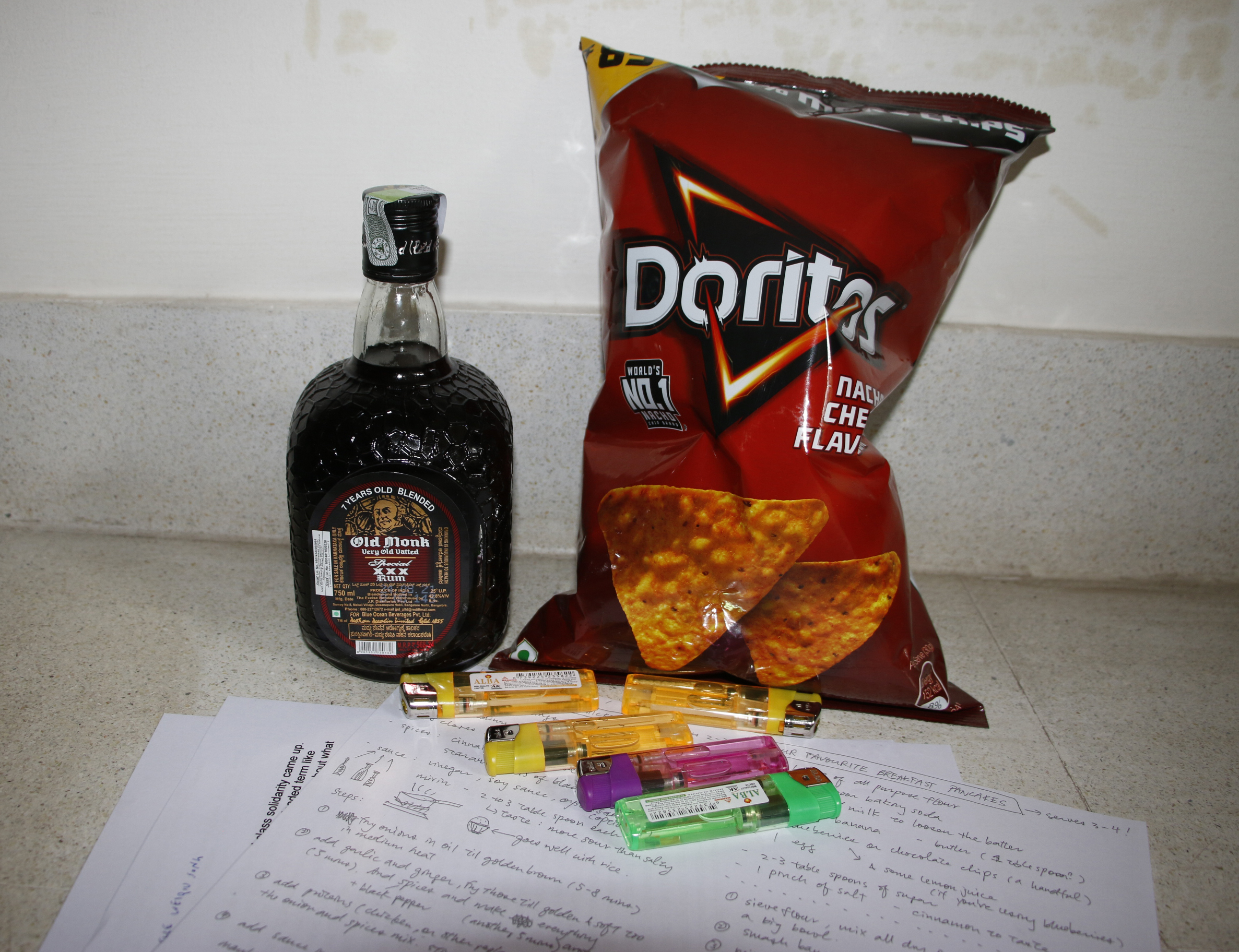

NF: Lantian’s contribution is three texts (No Look Pass by Michelle Weiqui Song, a text written as an accompaniment to a previous exhibition; a chicken Adobo recipe from his friend Michelle Wong’s Cookbook for Wing; and zoom zoom zoom, a choreography for a city by Amiya Nagpal) alongside 12 bottles of Old Monk rum, 25 plastic lighters, and 2 packets of Nacho Cheese Doritos. This assembly of things doesn’t refer to any particular past work of his, but it is still indicative of the moves and gestures of his practice, and in our reading is bibliographic.

Lantian Xie. “No Look Pass, Cookbook for Wing, Zoom zoom zoom, 12 bottles of Old Monk Rum, 25 lighters, 2 packs of Nacho Cheese Doritos,” 2021. at the kitchen table. Curated by Reliable Copy, 2021. 1Shanthiroad, Bangalore. Courtesy of the artist and Reliable Copy.

AV: Yes, the reason why I like this work so much is because, while it’s very firmly situated in his own practice, there’s also this sense of transference. People who encounter the Old Monk bottles in the kitchen in Bangalore will bring with them their own associations. Similarly, No Look Pass is a personal inventory of micro-gestures, instances of workers claiming something with improvised stealth, such as to take a meal at a noodle bar without it being detected or hiding a tip that would otherwise be stolen by the workplace ‘superiors.’ Every single employee who has worked under exploitative circumstances will understand what’s at stake in these gestures of subterfuge. No Look Pass is specific to the experience that is being described, but at the same time it’s open enough that it can be accessed. I found that interesting because the form (so to speak) of the recipe – if you look at it in a very broad definition as just the assembly of certain elements in the creation of a certain end result – is haunting the artworks as well. That approach recurs throughout, whether it is Fazal Rizvi or Candice Lin’s work, where the work’s form begins to disintegrate and take on new shapes.

SS: We keep talking about Lantian’s work as an assembly, but every work is now an assembly. Initially, we thought that each artist could share one representative document, but this hasn’t happened anywhere in the show except in the three videos (“Sushila’s Kitchen” by Gavati, “Rashtriy Kheer & Desiy Salad” by Pushpamala N, and “A Recipe for Disaster” by Carolyn Lazard), but that is simply because video is the one medium friendly to our efforts, both formally, as well as financially (in its hosting and sharing), in the form in which it already exists. However, in every other work, the artists have given us a combination of things that represents their particular work, so the idea of the “recipe,” as you put it, exists at various levels.

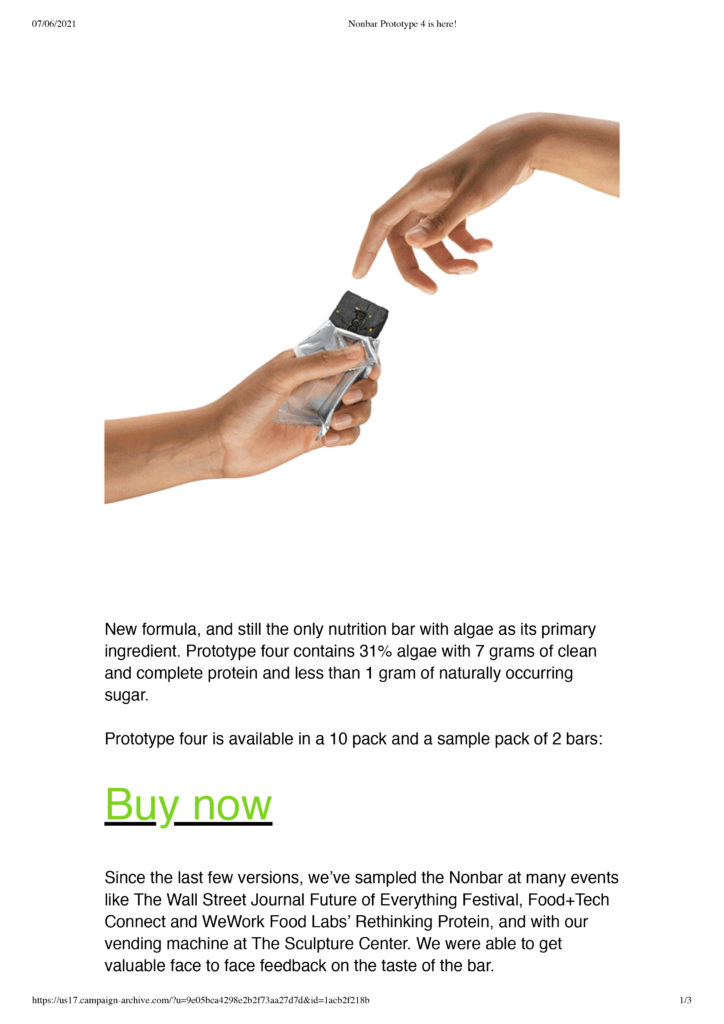

nonfood. “Email Campaign Archive,” 2017 – 2020. Email newsletter (facsimile). at the kitchen table. Curated by Reliable Copy, 2021. 1Shanthiroad, Bangalore. Courtesy of the artist and Reliable Copy.

NF: Which is also something embedded in our choice of title. If you say “at the kitchen table,” the table becomes the infrastructure upon which to convene and assemble, while also being the site where you enjoy the results of the recipe. Further, as an assembly, a lot of the things in the exhibition already exist in the public realm in some way, whether online or in publications. The video works are all accessible online and so are many of the other documents such as Abby Lloyd’s book Artists and Recipes, which is available as both a downloadable file and a print publication. In the case of Rasheed Araeen’s restaurant-as-artwork in London, Shamiyaana, we are showing photographs of the space that are already available on their website or on social media alongside an advertisement announcing the restaurant that was published in Frieze Magazine. In the case of Sean Raspet, Lucy Chinen, and Dennis Oliver Schroer’s algae-based food company nonfood, we’re showing an archive of newsletters sent to their mailing list with information about their products and company.

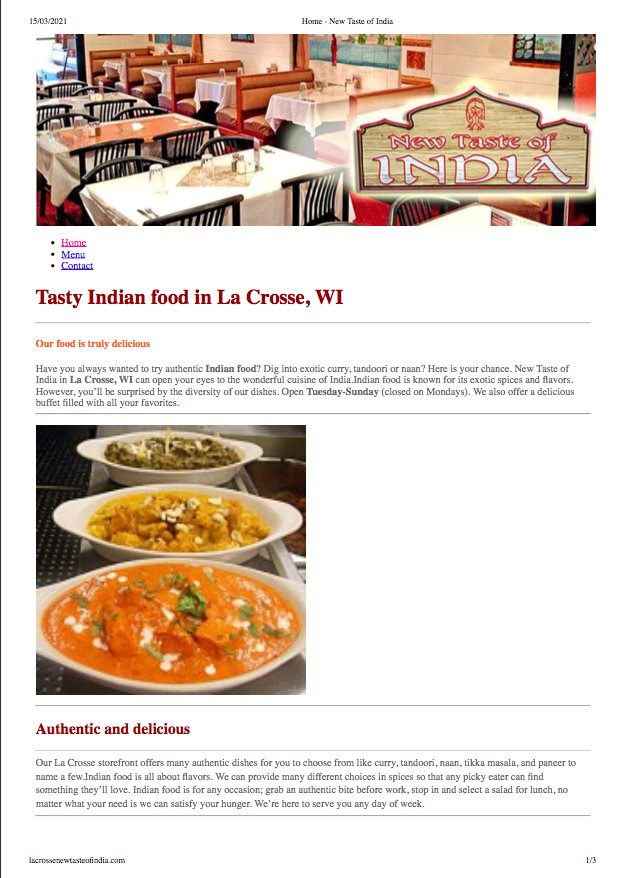

Rasheed Araeen. “Shamiyaana” (interior view). at the kitchen table. Curated by Reliable Copy, 2021. 1Shanthiroad, Bangalore. Courtesy of Grosvenor Gallery and Reliable Copy.

AV: I want to ask now about David Robbins’s “Ice Cream Social” and Nihaal and Chinar Shah’s “The Real Taste of India.” In both projects, there is a recipe – whether it is the recipe for an “ice cream social” event or for a Taste of India restaurant. In the former, this includes a Baskin-Robbins ice cream parlour, a poem, a one-evening gathering, a painting, and 31 flavours of ice cream. In the latter, it is a restaurant serving Indian food, perhaps a photo of the Taj Mahal, butter garlic naan, and Indian music: a combination that has been brought together in many cities. While they both gesture toward different themes and intents, there is a canopy of shared meaning that one can participate in.

David Robbins. “Ice Cream Social,” 2021. Slide from Keynote presentation. at the kitchen table. Curated by Reliable Copy, 2021. 1Shanthiroad, Bangalore. Courtesy of the artist and Reliable Copy.

NF: You are absolutely right. David’s contribution to this exhibition is a Keynote presentation charting the decades-long history of his “Ice Cream Social” project. Alongside this work being a set of instructions for an event at a Baskin-Robbins parlour, it is also a novella and a TV pilot – all of which are covered in the presentation. The “The Real Taste of India” project, on the other hand, is presented via three documents: the printed-out homepages of the various websites for different Taste of India restaurants around the world, a photograph of Chinar and myself outside a Taste of India restaurant in Mumbai that was associated with a previous exhibition, and take away coupons for free cold coffee, valid for the duration of this show, at the local Taste of India restaurant that first inspired this project.

Chinar Shah and Nihaal Faizal. “The Real Taste of India,” 2021. Webpage (facsimile). at the kitchen table. Curated by Reliable Copy, 2021. 1Shanthiroad, Bangalore. Courtesy of the artists and Reliable Copy.

SS: Those were two of the first works that we decided to include in the exhibition, and both practices also relate effortlessly to the curatorial premise of representing the work through secondary material.

NF: It’s also perhaps relevant to note that in both works there’s an idea of representing a national identity through commercialization, whether it’s the parlour-setting of Americana or the Indianness of a restaurant. There are other works that approach the idea of national identity and its representation head-on such as Pushpamala’s video, in which the artist is not just cooking a recipe, but also the concept of an “ideal” Indian family.

AV: There’s also a biographical element as she performs in the video.

Fazal Rizvi. “Document for a Proposal for a Monument for Zareen,” 2021. Exhibit C (facsimile).

SS: Yes, and the biographical element extends into other works in the exhibition, such as Fazal’s work which takes as its starting point his aunt’s sherbet recipe. His was the only work that we wanted to include that had no past version to begin with. Instead, we knew that for some time he had been interested in this sherbet recipe and this exhibition became a way to try and see what it could lead to. This resulted in a proposal document: “Document for a Proposal for a Monument for Zareen.”

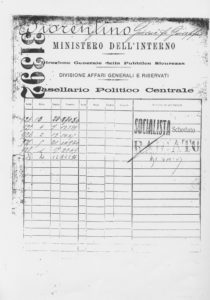

Leone Contini. “The Imagined Menu,” 2014. A page from the police report on Leone Contini’s great uncle Giosue (facsimile).

NF: Leone’s book, Ricettario Immaginato, which we discussed earlier, is similarly a familial document, while also exploring national identity through war, hunger, and food. Alongside his book we are showing a police report that was compiled about the same granduncle, parts of which are being translated to English for the show. Between these two documents – his diary of recipes and the police biography – the subject emerges as a ghost or an echo, a figure that is at once a prisoner, a writer, a dissenter, a political figure, and an uncle. All the artworks in the exhibition, many represented and reproduced in this slightly roundabout way, similarly become echoes or shadows or traces of a familiar form (that of the artwork).

AV: These are definitely running themes that also emerge in Jason Hirata’s work that lists the meals served in Japanese internment camps in the USA during the Second World War, or Gavati’s video “Sushila’s Kitchen” where she performs as a television cooking show host making a beef recipe without the main ingredient, following the beef ban in Maharashtra in 2015.

Carolyn Lazard. “A Recipe for Disaster” 2018. HD video, 29 minutes (still). at the kitchen table. Curated by Reliable Copy, 2021. 1Shanthiroad, Bangalore. Courtesy of the artist, Essex Street, and Reliable Copy.

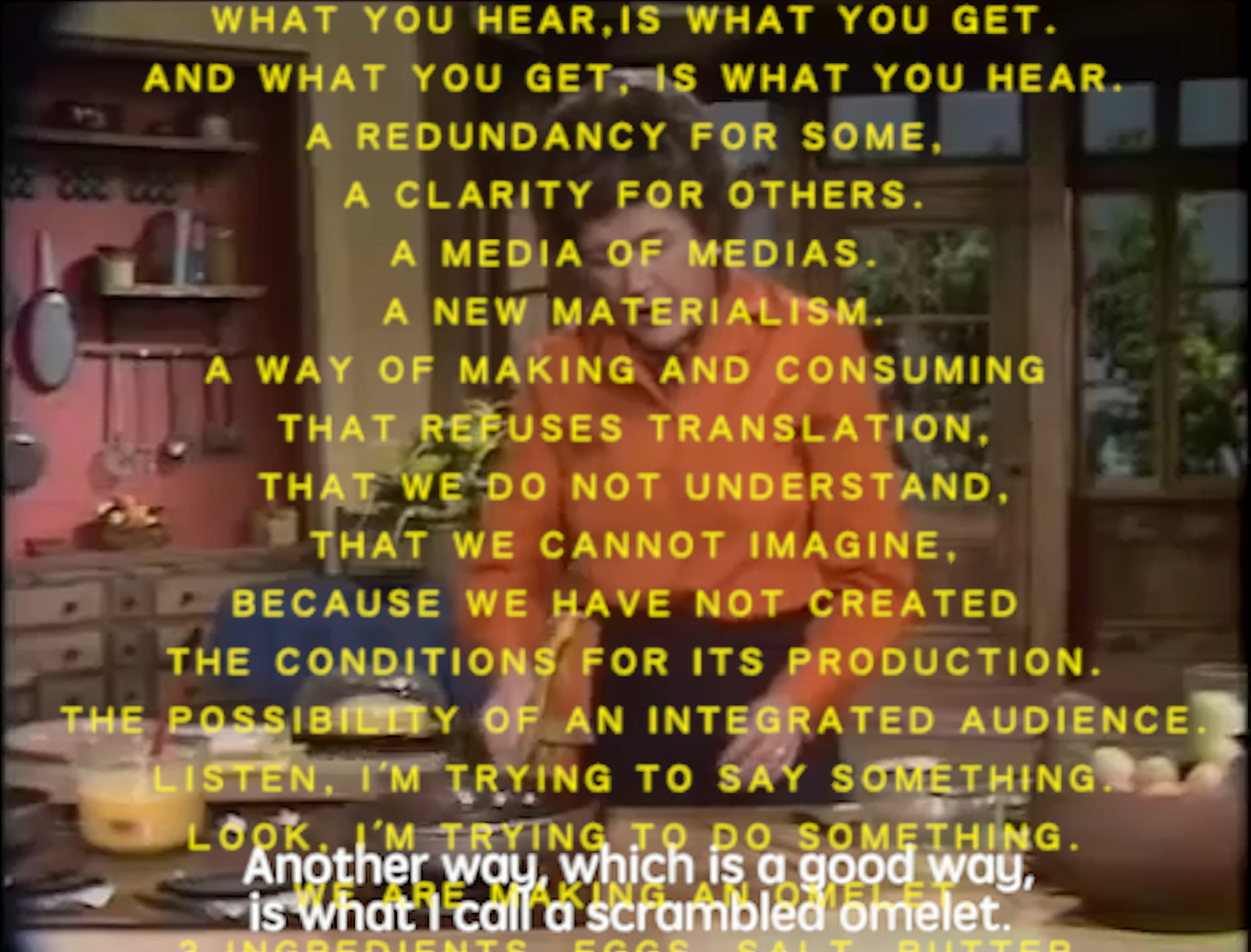

NF: Gavati’s work, which is situated within an experience of caste in Maharashtra, also leads us to Rajyashree Goody’s “Writing Recipes,” which is a series of booklets she makes with texts on food extracted from Dalit literature. For the exhibition, a selection of these publications is displayed alongside the books that they draw from. If these books can be considered “found material” then that also draws a line that leads to Carolyn Lazard’s “A Recipe for Disaster,” in which they layer an episode of The French Chef, a ’60s French cooking show whose ’70s rerun was known as the first show on American television to feature open-caption subtitles, an embedded scrolling text, a voice-over reading this text, and audio description, extending and complicating the levels of accessibility the show promised. So, while there is an idea of making the source visible (and the source document does appear as a recurring figure within the exhibition), there is also a transformative remaking and reframing that happens in the process.

SS: This is very acute in Jason’s work as well, which transformed entirely for this re-presentation. The work was originally a lecture performance where he read out the menu from an internment camp over the course of several days. In this re-performing, the work is now focused on a single day (June 1st, 1942) across multiple internment camps. In Jason’s case, there is also an aspect of his extended practice that informs our show greatly, which is his persistent grappling with the idea of the “supporting” role within artistic practice. In his previous works, he has examined his own supporting role as a videographer or technician for other artists in the making of their works, as well as the supporting role played by infrastructures of art spaces and presentation contexts in facilitating certain conditions of display and access. In this way, I feel that a lot of curatorial decisions, processes, and ideologies governing the show have been developed alongside the participating artists, or through a concentrated study of their wider practices.

AV: I also found this move interesting – lifting the veil on all sorts of collaborations that go behind making a certain end product of an artwork happen that this whole notion of art as a singular object or as a final event completely erases – something this exhibition is also doing. at the kitchen table is not interested in food that’s being cooked and put on the table. It’s interested in everything else that surrounds that. It makes you question who’s there in the kitchen, where the produce has come from, what the produce is, what the identity of the person cooking is, where they are cooking, and under what conditions are they cooking, and that’s something that I found really exciting.

When you think about what a cookbook does, you realize that a cookbook is a process. Every single manifestation of something that is made from a cookbook will be that thing and not be that exact thing at the same time. So, this whole tension between the idea and the form and the fact that both of them are not very stable entities is best captured in the form of a cookbook. All three of us could be looking at the same recipe with the same ingredients, and we could create the same food, but it would never be exactly the same.

At the same time, I was interested in the resistances to the document form because both nonfood and Candice’s “Subtleties and Warnings: Power and the Edible Grotesque” contain within them bodily processes that perhaps don’t translate very well when they take the document form. For instance, “Subtleties and Warnings” is based on the notion of food being hyper-sensory; engaging all senses and a performative encounter with scenography, excess, lavishness, and a whole array of feelings of shock, horror, and awe. And nonfood’s premise is also an embodied process — that of consuming algae. Reading about algae is not the same as using it as an ingredient. There’s a massive distance between the two.

SS: Where consumption is the key element.

AV: Right.

NF: That’s interesting because I don’t think we had thought of nonfood and Candice’s work being similar in that way, but you are right because one is very much about a history of eating, and the other about a proposed future. And both of them are also about consumption, but in a very packaged kind of way — whether it’s that of a grotesque and exaggerated celebratory feast, or through the corporate aesthetics familiar and popular today. These are also two forms of packaging that understand power – and don’t take it lightly.

AV: I hadn’t thought of the packaging, but yes! I was looking more at the bodily experience, but actually packaging is quite the key thing to look at here. Sometimes you have food that has very iconic packaging – you’ll have a book on McDonald’s or you’ll have a book on Betty Crocker. Then there’s literary characters such as Enid Blyton.

SS: This franchising and the merchandising concept is most visible through two books in this exhibition, Five Go Feasting, based on the “Famous Five” series by Enid Blyton, and Roald Dahl’s Revolting Recipes. There is a very specific idea of commercialization within this form – guiding it more than the literature, more than the narrative. You would never pick up these books if you didn’t already have a relationship with their source.

NF: The question of consumption is also a question of experience, right? Who gets to experience Lantian’s presentation, for instance? Unless you eat the nachos, or drink the rum, and even then, what is that? Consumption of 5% of the work?

SS: There is also the element of consumption in flammability. Where the combination of the lighters, the rum, and the Doritos, could very tangibly set something on fire.

AV: And once consumed, there would be no traces of this work left in the show. The bottles and the wrappers would disappear.

SS: Yes, there would be nothing. It wouldn’t come back as a leftover or souvenir, which is an important decision for us – what Nihaal mentioned about the form being a very important part of why something was selected. And apart from form, also the specific attitudes, strategies, and gestures that inform each of these practices. nonfood may have come to the forefront for both of us because it was an artistic practice that was functioning with a very specific direction.

NF: Yes, and there’s also the idea of distribution tied in, the minute the result becomes a product in a way that an artwork is not. A bar of algae is more like publishing, more like a cookbook. It’s a way of entering places that you didn’t have access to before – like start-up meetings and accelerators, but also homes and the supermarket. This role-playing can be quite freeing. It’s a way of working that’s dictated by the logic of a market, by the design of an industry, and by a certain balance between production, consumption, and distribution, but also through a playing-in-disguise. This is also a kind of standing in then, because at some point it is clear that even though these things appear to fit certain commercial models, they are informed by artistic or creative practices that are also involved in other fields. This is just as true for when Sarasija and I call ourselves Reliable Copy and play the role of a publishing house.

SS: Yes, a discreet way of standing-in. This is also what largely informed our selection of works. At some level, it wasn’t even about the work so much as it was about the artists’ practices and our affinities towards them. This standing-in is exaggerated in the case of nonfood or Shamiyaana, of course, but it’s equally true in how every artist in the exhibition extends the premise of their practice, and therefore practice at large – whether it’s Jason’s idea of the supporting role, or David’s theories of “high entertainment” and “concrete comedy.” Because otherwise this is a very bizzare list of artists. The only thing I can see which is truly in common is Nihaal and I want to work with all of them, one way or another.

NF: That’s our proposition as artists. Our motivation has simply been to be in dialogue with all of these practices, whether in the context of this exhibition or through what we do otherwise with Reliable Copy. In this case, maybe this dialogue is the show, maybe that’s all we have to present, really – and what everyone that enters the exhibition receives are just the traces of that process and moment.

Footnotes

Arushi Vats is a writer who lives in New Delhi, India.