Consuming Nature

Aeron Bergman and Alejandra Salinas

October 2021

Introduction by Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz

Can we criticize colonialism without criticizing capitalism? It is commonplace to think about European colonialism by way of imperial representations (Spanish colonialism, English colonialism, French colonialism, etc.), but that is only half of the story. While colonialism is important as a structural element with which to rethink history – and to engage with our present in terms of social justice, equality, and anti-racism – it is also important not to attribute colonialism solely to a flag or a crown, while leaving out the responsibilities of corporate interests and private investment in the colonial enterprise. In other words, the history of European colonialism is inseparably linked to the history of capitalism. The idea of freedom promoted by capitalist ideology and its so-called free markets might seem contradictory to the atrocious forms of racialized oppression, genocides, and ecocides of colonialism – horrors that continue today. However, once we understand the division of domains and shared responsibilities between imperial rule, private investors, and a global market, the factor linking 16th-century colonialism to contemporary forms of neocolonial and extractivist policies becomes evident: global capitalism, the perverse project that patents life and extorts natural resources from those who have paid for the wealth of persisting colonial powers with their blood and sweat – with their lives – for over 500 years to feed an insatiable system of greed and murder. In “Consuming Nature,” Aeron Bergman and Alejandra Salinas challenge us with a necessary paradigm shift in understanding the nature of colonial exploitation in order to analyze how it has continued up to the present day and to identify more ethical and sustainable alternatives.

Frans Post. Sugar Mill (ca. 1661). Based partially on Dutch West India Company’s Brazil colony but mostly an imaginary, exotic Dutch landscape.

GJ Chemical and Monsanto Co-promotion ad. Date. December 13, 2017. Designed by Janet Molchanko.

The verb “to colonize” is derived from the Latin word colonus, meaning “farmer, tiller, or planter,” linking colonialism to land and land use.1 Food production, after all, is the most important activity in a civilization; therefore, severing a people from their ability to produce food destroys their sovereignty. The Spanish knew this and rapidly prohibited the Inca, Maya, Aztecs, and other indigenous conquered peoples from cultivating their most important, nutritious, and sacred crop: amaranth. Similarly, today’s seed patent crusades, waged by multinational private enterprises, threaten to remove essential native plants from free and natural circulation.

Colonial paintings, such as the one above by Frans Post, offer a record of a fantasy land: an idealized, ordered, and exoticized European landscape set in the New World (that is, the undeveloped market) with native natural riches such as palm trees, sugar cane, or cacao beans growing in the foreground. These warped, nearly five-centuries-old colonial dreams continue to be projected onto the realities of neocolonized territories. In more recent images, print ads and commercials, made by the four multinational agribusinesses that monopolize 60% of the world’s seed trade, we see infinite rows of perfectly systematized, monetized crops under slogans of “progress,” indicating the dream of maximal privatized returns.2

Colonialism is Private Enterprise

From the “Age of Discovery” on, European colonialism was a private enterprise. In the case of Spain, the 16th-century conquistadors were soldiers of fortune expecting personal profit, financed by larger profit-seeking private enterprises, at no risk to the royal treasury. Campaigns depended upon the Crown of Castile only for legal authority.3 From the very beginning, the main beneficiaries of colonialism were chartered companies such as the 16th-century La Casa y Audiencia de Indias and the Welser Charter of Venezuela Province, which, while flying national flags, enjoyed unfathomable, privatized monopoly profits during their runs.4 In fact, already in the 17th century the English East India Company and the Dutch East India Company “pioneered features which later became textbook characteristics of modern corporations: a permanent capital, legal personhood, separation of ownership and management, limited liability of shareholders and directors, and tradable shares.”5

Progress Plunder

While the motivation for colonialism was straightforward (profit), the moral justification of it was more sophisticated and wrapped in religion and law. Based on assumed European superiority, colonialism was (literally) sold under the guise of “progress” and “development” both at home and abroad. For example, one key to Spanish rule in the Americas was the cooperation of indigenous elites: the Spanish utilized existing networks of power by offering the promise of technological and cultural “progress.”6 A small minority of Europeans benefited directly, and then an even smaller minority of indigenous and mestizo elites benefitted from collusion. The average citizen of European nations did not clearly benefit, and the majority of indigenous people in the colonized lands suffered immensely and died.7

Claims of development, innovation and progress also remain stable sales features for early to current day corporations. Central to colonial reasoning is the belief that European technological inventions are always preferable to indigenous knowledge and traditional practices, which the Europeans referred to as “primitive,”8 and that the bounty of colonial lands exists despite traditional farming knowledge, never because of it. Thus, European science is obligated to plunder. This line of thinking continues today, even though extensive archaeological evidence has shown that an estimated 60.5 million indigenous people in the pre-colonial Americas were supported by advanced farming methods such as irrigation, slash-and-burn agriculture, terraced fields, and home gardens.9

Vicente Albán, Indian Woman in Special Attire (India en traje de gala) (ca. 1783). Meticulous portrayal of local bounty with details of indigenous Ecuadorian crops with written plant and fruit information. Colonial painting emphasizing the idealized abundance of the land and its natural resources, measured using the devices of European science.

The centers of power and capital exert gravity to a greater or lesser degree depending on where one stands in relation to the system. To small farmers tilling the “developing” world using devalued, traditional forms of agriculture, the promise of gaining knowledge, advancements, and power from the center may be attractive. However, power and technological knowledge are concentrated through corporate interests and are not shared with benevolent intentions. Neocolonialism in the form of “development aid” is sold by the World Bank, IMF, etc. as “opportunity development” to create a path for the “developing world” to participate in global markets.10 Development initiatives are marketed with the idea that everyone could gain wealth if communities tap into the flow of technology and international trade. However, this path is designed for one-way movement: extraction from the margin to the center. Loans are made for infrastructure and other projects that appear to benefit a marginalized society, but “development” always arrives with conditions unfavorable to marginalized populations. While this extended hand could provide value if it were a decentralized system of knowledge and resource exchange, law and treaty determine the outcome of a transaction between center and margin. Implied by talks, referendums, and other forms that appear to be bilateral negotiation, law and treaty appear to be the arbiter of fairness and justice. However, legal features are always drafted through negotiations that reflect the coercive power imbalances between nations, imbalances reinforced with permanent military outposts.

Laws of Violence

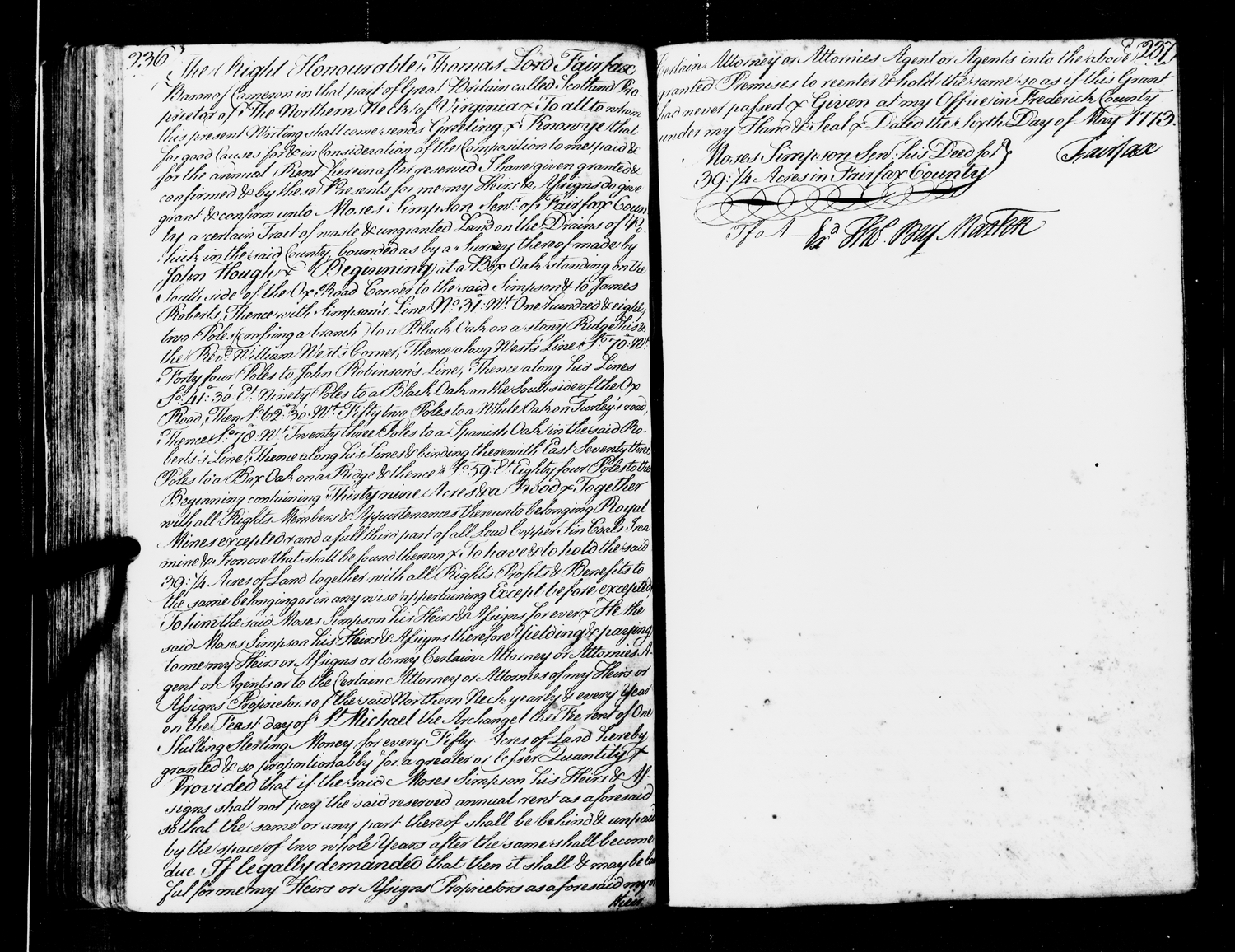

Colonialism was, and is, enforced by the violence of law. The Spanish Crown gave patents to companies over territories, authorizing conquest ventures through a formal contract or patent known as the capitulación. This contract granted the exclusive right to conquer a particular territory, specified the concessions in the newly conquered territories, rewarded the conquerors with percentages, and reserved rights for the Crown.11 Upon arrival, the Spanish conquistador would read aloud the untranslated legal document El Requirimiento, written by Spanish jurist Juan López de Palacios Rubios in 1513, stating Spain’s legal right to conquer and the consequences of indigenous resistance: “As to vassals who do not obey, and refuse to receive their lord, and resist and contradict him; and we protest that the deaths and losses which shall accrue from this are your fault.”12 By the 17th century, English “proprietors” (charter companies) were also granted exclusive crown “patents” for settlement areas of North America.13 Charter companies such as the Virginia Company then granted patents of individual allotments to settlers. Land patents were not deeds of ownership; they were licenses for exploitation.

Source: Library of Virginia, land patent granted by the Virginia Company to James Wren, April 5, 1773.

Patenting remains an important tool today as current neoliberal, neocolonial laws revolve around intellectual property. Intellectual property law is a powerful weapon, expanding its reach to important areas of human knowledge, custom, art, scientific research, agriculture and even life itself. Intellectual property laws are the privatized legal claims over knowledge developed and selected by humanity for thousands of years. Intellectual property law facilitates illegitimate claims of privatized ownership of the commons (via the patenting and copyrighting of seeds, plants, and images), expanding neocolonial methods of control of both physical and mental landscapes. Though legal complexity has increased, the heart of the matter is how the law enforces colonial violence.

Seed Patents

Life can be patented. The Diamond v. Chakrabarty Supreme Court ruling in 1980 stated that Congress intended patent eligible subject matter to “include anything under the sun that is made by man.”14 Subsequent rulings upholding and expanding life patents (in 1985, 2001 and 2013) built a legal stone wall out of an ethical and environmental disaster. In 2001, Supreme Court Justice (and former corporate Monsanto lawyer) Clarence Thomas wrote in a majority opinion stating that “the relevant distinction was not between living and inanimate things, but between products of nature, whether living or not, and human-made inventions.”15 Among the striking effects of the Supreme Court rulings on life patents is that farmers who use patented seeds can no longer save the seeds naturally generated by their crops. The seeds must be rented anew each growing season and cannot be replanted. This radically contradicts the very nature of plant reproduction and farming as practiced for thousands of years. Through this imperial enclosure of the commons, the inevitable end goal of plant patenting is the total monopoly of the global food market.

Agribusinesses, via interlocutors and lobbyists, market patented seeds to governments (and then to farmers) with the promise of “development” through technological innovation and access to international markets. Sowing monoculture cash crops promises expansion of production, higher yields, exponential financial returns, and emergence into “developed world” status. Studies have found that agribusiness crops have not increased yields generally, and when higher yields occasionally result, quality falls.16 Agribusiness obfuscates the risks, such as susceptibility to disease and drought, that go along with cash monoculture and downplays the substantial increase in upfront costs – on seeds, chemicals, machinery, and more – that farmers must bear. Monsanto’s (now Bayer’s) patented soybean seeds are not only more expensive at buy-in but also more costly to maintain, as the crop depends on specific herbicides and pesticides. Further, farmers must repeat these considerable expenses annually, locking them into a one-sided relationship with a corporation.

William Merritt Chase, The Nursery (1890). In the art collection of Bill Gates. Purchased for $10M. Portrait of white, upper class leisure in landscape.

Foundation of Power

Following the 18th- and 19th-century principles of “market freedom” developed under colonialism, neoliberalism formed as a strategic and rhetorical return to liberalism, thus directly connecting colonialist principles with capitalist markets today.17 One of the major forces in world agriculture today is the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The foundation tirelessly trumpets public-private initiatives and happy-sounding “open” markets – the essence of neocolonial, neoliberal policy.18 The main priority of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is innovation and technology. The foundation claims to be investing in “developing countries,” focusing “on improving people’s health and giving them the chance to lift themselves out of hunger and extreme poverty,”19 and yet most of its funding goes to the richest US and European institutions that actively promote patents and other one-way market relationships with the developing world. Eight out of the top ten beneficiaries of the Gates Foundation research funds are US universities.20 Despite their claim that Africa is their primary sector, only 11% of their university grants go to African universities, with the majority of that going to just two: University of Cape Town and the Federal Agricultural University of Nigeria.21 The Gates Foundation has given over $206 million to Harvard University, the richest university in the world, and nothing to South American universities. The Foundation’s “Strategic Investment Fund” also invests massive amounts in agribusiness companies such as Monsanto/Bayer, Cargill, AgBiome and Enko Chem, thus forming a perfect feedback loop of power.22 By lobbying for and then profiting from extraction, the Gates Foundation consolidates increasingly massive power to reshape the world in their idealized image of a global market based on imperialist and thus fundamentally racist principles. Cargill, for example, has been criticized in Brazil’s ongoing indigenous protests and legal fights for destroying the Amazon rainforest in order to plant monocrops.23

Infinitely Barbarous

Early philanthropy in the North American colonies also emphasized doing “good” while actively perpetuating suffering. The Massachusetts Bay Colony (founded by owners of the Massachusetts Bay Company) founded Harvard College as a seminary to “advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity: dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches.”24 The Harvard Indian College was established in the 1640s with financial support from British charitable organization Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England (also known as the New England Company or Company for Propagation of the Gospel in New England and the parts adjacent in America). The Harvard Indian College, established in 1655 and closed in the 1670s, is known for printing the first translation of the Bible into the native Natick language and for the untimely deaths of its few native students (only five are recorded, with only one graduate) resulting from infectious diseases spread by close contact with English colonists.25

Cotton Mather, an early Harvard graduate, theorist and Puritan theologian, advocated a familiar philanthropy: “Let no man pretend to the name of a Christian who does not approve the proposal of a perpetual endeavor to do good in the world.”26 Mather presided over the Salem Witch Trials and recorded observations on plant hybridization, specifically native corn. Cotton’s father, Increase Mather, president of Harvard College, wrote the following observations about the native Massachusett people:

They live in a country full of the best ship-timber under heaven: but never, saw a ship till some came from Europe hither; and then they were scared out of their wits to see the monster come sailing in, and spitting fire, with a mighty noise, out of her floating side. They cross the water, in canoes made sometimes of trees which they burn and hew till they have hollowed them; and sometimes of barks, which they stitch into a light sort of a vessel, to be easily carried over land; if they over-set, it is but a little paddling like a dog, and they are soon where they were. Their way of living, is infinitely barbarous: the men are most abominably slothful; making their poor squaws, or wives to plant, and dress, and barn, and beat their corn, and build their, wigwams for them; which perhaps may be the reason of their extraordinary ease in child-birth.27

Although Harvard’s current “commitment to diversity” at home is backed by its sector-leading 53% BIPOC enrollment stats for 2021, Harvard’s economic strength is supported by the largest university endowment fund in the world, earning rolling dividends through active colonialist investing. The Harvard endowment fund, partnered with TIAA since 2008, has amassed a combined total of around 750,000 hectares of farmland in Brazil. These farmland deals are connected to illegal land grabbing by fraudulent legal title claims to public lands, violent displacement of local rural communities, deforestation, and clearing through major forest fires for expanding monocropping plantations.28 The Harvard endowment’s landholdings were ruled illegal by Brazil’s land agency and the state court of Bahia in 2019.29

It is tempting to say that the early colonies were religion-driven, and that motivations and methods are now different. However, vague claims of spreading religion to the “heathens” and vague ideals of “development” and “goodness” to the “hungry” were and remain excuses to develop markets advantageous to settlers. Today’s religious fever is even more transparent: the faith in the market, technology and capitalism drives massive, destructive disruption.

Corteva Agriscience, “Stand On Common Ground,” YouTube video, 1:40, 30 Nov. 2020, screenshot: 15 Aug. 2021, https://www.corteva.com/resources/feature-stories/the-diverse-voices-in-agriculture.html. Corteva is an agricultural chemical and seed company created as a result of the Dow–DuPont merger. This video represents part of their diversity advertisement campaigns.

Higher Yields for Whom: Agrarian Extractivism

Already in 1964, Che Guevara saw farm monopolies as a tool for neocolonial oppression:

It is incontrovertible that present-day prices are unfair; it is equally true that prices are conditioned by monopolist limitation of markets and by the establishment of political relationships that make free competition a term of one-sided application; free competition for the monopolies; a free fox among free chickens! . . . The world is hungry but lacks the money to buy food; and paradoxically, in the underdeveloped world, in the world of the hungry, possible ways of expanding food production are discouraged in order to keep prices up, in order to be able to eat. This is the inexorable law of the philosophy of plunder, which must cease to be the rule in relations between peoples.30

Seed-saving allows growers to develop gene-diverse plants that are more adaptable to the changing demands of the local environment, providing resilient food sovereignty. Farmers, attracted to dubious claims of the advanced technology that will provide higher yields, give up control of their crops and pay a massive premium on their seeds, leading to proliferating monocrops: 75% of the world’s food is produced from 12 plants – and, of those, mostly just from corn, wheat, rice and soybeans. This overdependence on essentially four major crops leaves food supplies vulnerable to climate change, disease, drought and any number of factors of which tech-heavy plant science cannot keep up with. Consequently, the risks of monocrop failure and debt-induced farm bankruptcies have increased exponentially around the world. Wide-spread farm failures resulting from risky relationships with agribusiness have been displacing people, ruining lives and leading to a rise in suicide among farmers. Family-held, small farmlands are being consolidated into international private equity portfolios. Even when cash crops are successful, this comes at the expense of the long-term health of the soil. Chemical-intensive farming also puts farmers at risk of cancer. Furthermore, in the so-called developing world, soybeans are pipelined for the international market as cheap, raw-material commodities rather than as more valuable processed food and goods, a process known as “agrarian extractivism.”31

Translation: “Sooner or later. Always DEKALB,” DEKALB Argentina advertisement, 2020. DEKALB corn seed company was bought by Monsanto in 1998, and Monsanto was bought by Bayer in 2017.

Food Monopoly

Seed power has shifted from small seed growers and companies to giant monopolies. In 1996, there were six hundred independent seed companies operating in the United States alone. By 2009, this number had shrunk to one hundred, and by 2016 the ten biggest seed sellers controlled 75% of the global market. By 2019, four big seed companies controlled more than 60% of global proprietary seed sales: Bayer/Monsanto, Corteva (a firm created as a result of the Dow–DuPont merger), ChemChina and BASF, and they relentlessly consolidate and increase ownership of global genetic material.32 The promise of progress and development via the techno-optimism of lab-based farming that is sold to global farmers and governments as a promise of participation in world economics is mostly a neocolonial strategy of control and extraction.

Control over seeds is in many ways control over food supply, and it is not a controversial statement to say monocropping endangers gene diversity. In the late ’60s and ’70s, the US Department of Defense, World Bank, United Nations and other agencies started to grow concerned that monoculture and seed concentration were destroying biodiversity and endangering the world food chain by neglecting a wide range of crops needed to grow and adapt.33 Instead of restricting seed monopoly, patenting and dangerous monoculture, Western world governments and corporate agencies proposed naive technological optimism (faith in innovation) through a world network of genome banks and databases.34 Yet, in order for plant genome varieties to be healthy, they have to be in use, seasonally growing, and allowed to adapt to their environment. World gene banks are not supplied with funds to keep the seeds alive by maintaining and circulating the seed genome because they are not immediately and obviously useful to capital. These underfunded genome and seed bank systems are directionless and are sometimes referred to as seed graveyards.35 Seed banks are purely symbolic, will not hedge disaster, and thus do not solve the problems that seed monopolies cause.

Rosa Elena Curruchich. Rosa Elena painting Ochosij farmhouse (ca. 1980s). The artist painting amidst Guatemalan farmland.

It Doesn’t Have to Be This Way

There are alternatives. Indigenous knowledge is our shared scientific heritage. When indigenous knowledge and scientific advances are freely shared, the benefits are bilateral. This heritage includes traditional agricultural practices such as seed saving and initiatives that encourage collaboration such as living, breathing community seed libraries. Initiatives that acknowledge indigenous knowledge of care and mutual respect and dependency with the land, such as small growers and farmers’ networks, could expand into semi-organized knowledge- and resource-sharing networks. Through collaboration and protecting the commons, law can also be reclaimed as a tool to defend against colonial incursions. Contract law, such as open source seed licenses, protects the free use of seeds, preventing their privatization.

The “developing world” has tended the world’s biodiversity for thousands of years, yet patented monocrops are not the solution to food security issues. Distributed, de-centralized knowledge is needed to combat agricultural neocolonization. If Harvard’s (and MIT and University of Washington’s, etc.) endowments and knowledge were redistributed widely to other universities, farmers, and communities; if open science was practiced above market-oriented science; and if resource extraction were negotiated on bilateral cooperation; the resulting global flourishing would make it starkly apparent that hunger is a planned feature of capitalism, and not the solution. But instead, plant patenting and monocropping continues its crashing march forward: an excellent, short-term business strategy for resource extraction – not an efficient, stable world food source. It is not even controversial to state that monoculture of only four crops is not a sustainable and dependable food source for the world. Nevertheless, the propaganda of extractionist, neocolonial capitalism is so strong it drowns out the warnings.36

Amaranth

Amaranth survived its colonial prohibition not only because it was a beloved, sacred crop, but also because it is extraordinarily resilient. Amaranth was an essential crop for the Inca, the Maya, the Aztecs, the Mississipean culture centered in Cahokia, and widely across the Americas. Amaranth is popular today due to its health benefits and genetic diversity.37 However, in a turn of schadenfreude: wild amaranth has also developed into a “superweed” that grows so fast – and adapts so easily – that it is choking out fields of agro-tech monocrops.38 Wild amaranth has been identified as one of the most severe threats to corporate farming. Gates Foundation-backed startup Enko Chem recently announced its joint venture with Bayer to “develop solutions” against superweeds, naming amaranth specifically as the “king of weeds.”39 Agribusiness responds by using even more herbicides, but amaranth learns how to adapt faster than corporate scientists figure out how to kill it. Amaranth’s will to survive is remarkable. It would be comedy if it weren’t also tragedy: switching from massive monocrop fields to amaranth and a wide variety of traditional, hearty and diverse crops would entail a cultural change that seems too large to imagine.40 However, this change is significantly more manageable than the famines that will result from disease, climate change, ravaged crops and the other serious ethical and scientific failings of the colossal monopolies of our global food system in this age of kleptomania if we do not take alternative action.

A Mississippi soybean field with glyphosate-resistant amaranth weeds in the foreground. Photo by Yanbo Huang for the US Department of Agriculture. Public Domain.

Aeron Bergman and Alejandra Salinas, “Consuming Nature” (2021), audio 34:09.

Production, editing and sound design by Aeron Bergman and Alejandra Salinas. Thanks to the interviewees, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz for your support and conversations, The Luminary in St. Louis, and MARCH.

Interviews include: Dr. Kū Kahakalau (Hawaiian educator, researcher, cultural practitioner, grassroots activist, and expert in Hawaiian language, history and culture), Irwin Goldman (professor in the Horticulture department, University of Wisconsin-Madison), Ronaldo Eleazar Lec Ajcot (co-founder Mesoamerican Permaculture Institute, Guatemala), Bill McDorman (co-founder Rocky Mountain Seed Alliance), Kelly Wilson and Justine Hernandez (Seed Librarians, Pima County), and Jack Kloppenburg (secretary, Open Source Seed Initiative and professor emeritus, University of Wisconsin-Madison).

All sounds are Public Domain and/or Creative Commons 3.0.

Sound Attribution:

Brian Flood (flood-mix), “Costa Rican Oropendolo”

Leon Septavaux (leonseptavaux), JUNO-60 synth chords on empty wine silo

mugwood, Gentle Waves Peeling Left to Right

—

Introduction: Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz is a Bolivian-German philosopher and curator, living in La Paz. He was the director of Bolivia’s National Museum of Art (Museo Nacional de Arte, MNA) in La Paz, and is currently artistic director of Akademie der Künste der Welt in Cologne. From 2014-2016 he was coordinator of São Paulo’s Seminário Público Micropolíticas and Programa de Ações Culturais Autônomas (P.A.C.A., together with Suely Rolnik, Tatiana Roque and Amilcar Packer).

This essay has been published in partnership with The Luminary as part of their Residency Program.

Footnotes

- Lea Ypi, “What’s Wrong with Colonialism,” in Philosophy & Public Affairs vol. 41, no. 2 (Spring 2013): 158-191, 160.

- OECD, Concentration in Seed Markets: Potential Effects and Policy Responses (Paris, OECD Publishing, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264308367-en.

- Ronald W. Batchelder and Nicolas Sanchez, “The encomienda and the optimizing imperialist: an interpretation of Spanish imperialism in the Americas,” in Public Choice vol. 156, no. 1/2 (July 2013): 45-60, 47.

- There are many later examples such as the Dutch West India Company, Dutch East India Company, South Sea Company, Canada Company, Royal Niger Company, and Company of Venture Adventurers of London, etc.

- Oscar Gelderblom, Abe de Jong, and Joost Jonker, “The Formative Years of the Modern Corporation: The Dutch East India Company VOC, 1602–1623,” in The Journal of Economic History, 73.4 (2013): 1050-1076, 1050.

- Many books have documented these collaborations, including Sean F. McEnroe, A Troubled Marriage: Indigenous Elites of the Colonial Americas (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2020).

- It is estimated that 80% of the indigenous population died, mostly from infectious disease brought by the Europeans, but also through slavery and murder. See: Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017).

- Any claims of European superiority are not only racist but clearly ahistorical, since European advancements in farming were paralleled by indigenous farming methods, and it was not European armed superiority that killed 80% of the indigenous population, but European diseases. See: Alexander Koch, Chris Brierley, Mark M. Maslin, and Simon L. Lewis, “Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492,” in Quaternary Science Reviews, vol. 207 (2019): 13-36.

- Alexander Koch, Chris Brierley, Mark M. Maslin, and Simon L. Lewis, “European Colonization of the Americas Killed 10 percent of the World Population and Caused Global Cooling,” in The World (2019), https://www.pri.org/stories/2019-01-31/european-colonization-americas-killed-10-percent-world-population-and-caused.

- Mueni wa Muiu, “‘Civilization’ on Trial: the Colonial and Postcolonial State in Africa,” in Journal of Third World Studies, vol. 25, no. 1 (2008): 73-93, 86-87.

- Batchelder and Sanchez, “The encomienda and the optimizing imperialist,” 48.

- Juan López de Palacios Rubios, El Requerimiento (1513), https://tinyurl.com/4hreazn5.

- Scottish economist Adam Smith writes, “The first English settlers in North America […] offered a fifth of all the gold and silver which should be found there to the king, as a motive for granting them their patents.” See: Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (London: Strahan and Cadell, 1776), 423. See also: New York State Archives, https://tinyurl.com/ymzc8hrk.

- “Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303 (1980),” https://tinyurl.com/4t4bhy2r.

- Ibid.

- Research consultant Doug Gurian-Sherman writes, “If we are going to make headway in combating hunger due to overpopulation and climate change, we will need to increase crop yields (and) traditional breeding outperforms genetic engineering hands down.” See: Doug Gurian-Sherman, “Failure to Yield, Evaluating the Performance of Genetically Engineered Crops,” Union of Concerned Scientists, 2009, https://tinyurl.com/7ar9jetz; and Joe Bavier, “How Monsanto’s GM Cotton Sowed Trouble in Africa,” Reuters, 8 Dec. 2017, https://tinyurl.com/f6upa2s6.

- Filipino American literary academic Epifanio San Juan Jr. stated, “Propped by the Pentagon-supported military, the Arroyo administration today, for example, uses the U.S. slogan of democracy against terrorism and the fantasies of the neoliberal free market to legitimize its continued exploitation of workers, peasants, women and ethnic minorities.” See: Epifano San Juan Jr., “Imperial Terror, Neo-Colonialism and the Filipino Diaspora,” a lecture delivered at the 2003 English Department Lecture series at St. John’s University; British-born Marxist economic geographer David Harvey stated, “Although neoliberalism has had limited effectiveness as an engine for economic growth, it has succeeded in channeling wealth from subordinate classes to dominant ones and from poorer to richer countries.” See: David Harvey, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 610 (2007), 22-43.

- The foundation’s website states, “Their crops and livestock are often far less productive than those in other developing regions, and they frequently lack access to market opportunities that can support investments in better inputs, tools, and farming practices.” See: “Agricultural Development,” Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, 22 Aug. 2021, https://www.gatesfoundation.org/our-work/programs/global-growth-and-opportunity/agricultural-development. In an interview, former director of the Bill & Melinda Gates Strategic Investment Fund Julie Sunderland stated, “We know that the transaction costs of selling to the poor are high. We know that the distribution channels and the infrastructure to reach these populations are underdeveloped. We know that there’s not a lot of information about these markets. We believe that the way to do that must involve innovation, whether it is technology or business model innovation. We’ve seen how leapfrog innovation enables you to lower transaction costs and achieve high volumes with products that can change people’s lives.” See: David Bank, “Leveraging the Balance Sheet,” in Making Markets Work for the Poor, ed. Paul Brest and David Bank, Stanford Social Innovation Review in collaboration with ImpactAlpha for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (2016), https://tinyurl.com/2c392dhz.

- “Mission Statement,” Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, https://equal-footing.org/funders/GATE023/.

- GRAIN, “How does the Gates Foundation spend its money to feed the world?” 4 Nov. 2014,

https://grain.org/e/5064.

- GRAIN, “How the Gates Foundation is driving the food system, in the wrong direction,” 17 June 2021,

https://grain.org/en/article/6690-how-the-gates-foundation-is-driving-the-food-system-in-the-wrong-direction.

- The Gates Foundation Strategic Investment Fund maintains a list of its portfolio. See: “Portfolio,” Gates SIF, https://tinyurl.com/6naeraas.

- Andrew Fishman, “Brazil’s Indigenous Groups Mount Unprecedented Protest Against Destruction of the Amazon,” The Intercept, 28 Aug. 2021, https://tinyurl.com/7c9awxfx.

- “Harvard’s Founding,” in The Harvard Crimson, 6 Oct. 1884, https://tinyurl.com/2myw78ya.

- Drew Lopenzina, Red Ink: Native Americans Picking up the Pen in the Colonial Period (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2012), 88.

- Cotton Mather, Bonifacius: An Essay upon the Good (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1966), 20.

- Cotton Mather and Increase Mather, “The triumphs of the reformed religion, in America. The life of the renowned John Eliot; a person justly famous in the church of God, not only as an eminent Christian, and an excellent Minister, among the English, but also, as a memorable evangelist among the Indians, of New-England; with some account concerning the late and strange success of the Gospel, in those parts of the world, which for many ages have lain buried in pagan ignorance” (Boston: Benjamin Harris & John Allen, 1691).

- Felipe Alfonso, “Harvard’s Farmland Investments in Brazil,” in ReVista Harvard Review of Latin America (July 2021), https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/harvards-farmland-investments-in-brazil/.

- AATR, Rede Social, GRAIN, “TIAA and Harvard’s Brazilian farm deals judged illegal,” 17 Dec. 2020, https://grain.org/en/article/6588-tiaa-and-harvard-s-brazilian-farm-deals-judged-illegal.

- Che Guevara, “On Development (speech, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 25 Mar. 1964),” Marxist Internet Archive, https://tinyurl.com/376fhnhd.

- Ben M. McKay, “Agrarian Extractivism in Bolivia,” in World Development vol. 97 (2017): 199–211.

- Camilla Hodgson, “Monopoly and Monoculture,” in Medium, 17 Jul. 2018, https://medium.com/the-food-issue-weapons-of-reason/global-food-industry-monopoly-monoculture-growing-corporate-profits-3df0ae5f7237.

- A joint meeting on plant exploration and conservation was convened in 1967 with a view to developing a strategy for genetic conservation, sponsored by the International Biological Programme (IBP) and the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). In the first publication that resulted from the Joint Meeting to focus on genetic resources conservation, Frankel and Bennett (1970) argued that long-term seed storage (that is, seed banking) was “the most urgent single measure at the present time to ensure genetic conservation.” See: Sara Peres, “Saving the gene pool for the future: Seed banks as archives,” in Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, vol. 55 (2016): 96-104,100.

- Between 1972 (when FAO and the CGIAR envisioned a World Network of seed) and 2010, 7.4 million samples (of which 1.5–2 million are thought to be unique) were stored in 1,750 genebanks around the world. See: Peres, “Saving the gene pool,” 98.

- Arguments in this paragraph are from conversations with Professor Emeritus Jack R. Kloppenburg (Open Source Seeds Initiative) and Bill McDorman (Seed Trust).

- The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation included “feeding the world” in its objectives in the early 2000’s. In a rare moment of self-reflection, the foundation changed this top-down paternalistic slogan into the even more patriarchal goal: “To ensure that all women and children have the nutrition they need to live a healthy and productive life.” See: “Nutrition,” Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, https://www.gatesfoundation.org/our-work/programs/global-development/nutrition.

- National Research Council, Amaranth: Modern Prospects for an Ancient Crop (Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 1984).

- H. Clare Brown, “Attack of the Superweeds,” New York Times 18 Aug. 2021, https://tinyurl.com/526d953s.

- Jacqueline Heard, “Joining Forces with Bayer to Help Farmers Tackle Weeds,” 27 Jul. 2021, https://tinyurl.com/5y37w5ne.

- Researchers Anu Rastogi and Sudhir Shukla write, “Amaranth, an underutilized crop and a cheap source of proteins, minerals, vitamin A and C, seems to be a future crop which can substantiate this demand due to its tremendous yield potential and nutritional qualities, also recently gained worldwide attention. Recently, current interest in amaranth also resides in the fact that it has a great amount of genetic diversity, phenotypic plasticity, and is extremely adaptable to adverse growing conditions, resists heat and drought, has no major disease problem, and is among the easiest of plants to grow in agriculturally marginal lands.” See: Anu Rastogi and Sudhir Shukla, “Amaranth: A New Millennium Crop of Nutraceutical Values,” in Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition vol. 53 (2013): 109-125.

Aeron Bergman and Alejandra Salinas are an artist duo. Currently living in Portland, Oregon where both are professors at Pacific Northwest College of Art, they have been active internationally in many forms and contexts since 1999.