Giveaways / Hideaways

Antoine Turillon and Seth Weiner

February 2024

Surrounded by rolling green hills, an expansive horizon, and farmland as far as the eye can see, the village of Lungitz lies along the Summerauerbahn, a railway line built around 150 years ago that connects the regional economic center of Linz, Upper Austria to Budweis/České Budějovice in the Czech Republic. Home to roughly 200 inhabitants, Lungitz has a hardware store that sells meat, beer, mittens, and concrete (which closes for lunch), a former restaurant undergoing perpetual renovations, and a row of large, freshly painted houses with flowers hanging from their balconies and robots mowing a patchwork of lawns that push up against its main road. Its summers are almost arid, the winters gray with a blanket of stillness, and no matter the season, the empty hills remind you of just how deep the ground is below your feet.

While preparing a public art commission in November 2022 for Festival der Regionen (FdR) in Upper Austria, we got a WhatsApp message with a large batch of images of the decommissioned Lungitz train station as a potential site. Sandwiched between the main road of the village and the railroad tracks, the Lungitz train station sits higher than all of the other houses. Slated to be demolished in some upcoming future, the station is already undergoing its replacement by an automated ticket machine and a glass box for shelter.1 Most of the images we received looked like you’d expect, empty spaces filled with traces of the past here and there. However, in one image, there were about twenty bags filled with gray dirt and stones pushed into the corner of a small room.

As one of the largest built structures in the area (second only to the grain tower), the Lungitz train station offers an overview of a farming village on one side and a former industrial zone on the other. Where the Gusen III concentration camp and a brick factory once stood, there’s now a concrete plate flanked by the local fire station and an elaborate fitness park for kids. Built around an industrial bakery that produced bread for inmates of nearby camps, the Gusen III subcamp was in use from 1943 until 1945 and was part of the larger Mauthausen/Gusen concentration camp network. Today, there’s no mention of the fact that the station is one of the last remaining architectural eyewitnesses to the concentration camp, nor is there any signage designating its history. Only a tall tree line and a gravel access road point to the past, but the structures that haunt the landscape remain invisible.

In 2018, this obscured past caught up to the present when a skeleton was discovered buried beneath the tracks of the Lungitz train station during renovations.2 The skeleton was dated back to the early Middle Ages, but during the excavation process, a layer of ash was uncovered. Due to the train line’s proximity to the Mauthausen and Gusen concentration camps, as well as the central role the railway played in Nazi infrastructure, it was suspected that the ashes were from the nearby concentration camps. Renovations were then halted and a team of archaeologists found that the chemical composition of the ash was identical to that of the ash from the nearby crematoria at the Mauthausen concentration camp.3 A 200-meter trench was then excavated underneath the train tracks. The ash was separated from the residue of the cremation process (slag) and buried in a commemorative grave next to the Gusen III concentration camp memorial stone.4

(Top Row) Lungitz train station details; arrested time, living quarters, and slag, the uneasy surfaces where the past meets the present. (Bottom Row, Left) A single-lane road passes under the tracks, turns into gravel, and lands at the memorial site. (Bottom Row, Center) View to Lungitz from the former Gusen III concentration camp. (Bottom Row, Right) Just beyond the train tracks, a row of Schrebergärten (allotment gardens) runs along a road surrounded by agricultural fields. Toward the top of the hill, a casino for SS officers looked over the Gusen III concentration camp and bakery. Photos: Antoine Turillon (2022)

During the process of sifting and separating the ashes, a large amount of slag was left behind. Some of it was transported to the Mauthausen memorial, some was archived at the University of Vienna (which conducted the analysis), and some, as we found out via that WhatsApp message, was left behind in a room at the Lungitz train station. Even though the slag was interwoven with the ash, scientifically it was deemed to be irrelevant for the grave because it didn’t show any traces of human remains in its chemical makeup. Nevertheless, the slag was diligently bagged and tagged with labels, making it clear that it was politically delicate. Back in the fall of 2022, when we started working on the project, the bags were still sitting in limbo in the train station, without anyone taking responsibility for their existence. As remains of the remains, they represented the uneasy surface where the past meets the present.

Faced with this discovery, the site, the building, and its meaning completely changed. Up until that point, our conversations had concentrated on how memory is something that’s active, how it has to be continually worked on and renewed, how it needs to be given away over and over again to remain visible, and how it can be non-competitive. But the discovery of the bags of historic “leftovers” situated the Lungitz train station at the center of the violence and trauma of the site. What do you do with an artifact of such extreme violence? Do you try to transform it, relocate it, or move it into a spotlight? Seventy-seven years after the end of the Second World War, the train station had become an accidental monument to the Gusen III concentration camp, but its monumentality remained hidden from view.

One of the last remaining architectural eyewitnesses, the Lungitz train station sits marooned on an asphalt island, quietly staring at the absence of the Lungitz/Gusen III concentration camp. Photo: Antoine Turillon

To explore how multiple directions of time, identity, and history could come into contact with each other, we decided to bring together a group of artists and historians from a diverse range of backgrounds to collectively search for and propose new forms of public engagement around this site. Leading up to the exhibition, we met with the participating artists and historians to talk about the role of art in this context, the commodification of remembrance, and how different forms of grieving, mourning, and joy can exist simultaneously. As this process unfolded, we slowly explored ways to turn the site inside out; we discussed approaches to architectural and artistic interventions, guided and independent tours, and the baggage of our respective backgrounds. The majority of artists currently based in or from Austria dealt with layers of history through their families, a sense of inherited guilt, and practices dedicated to understanding a collective past, while the remaining artists without a direct connection to the country dealt with regular encounters of being “othered,” ostracized, and alienated. In part, the discussions became about processing a past as well as trying to understand the current political context around us and how we can function in its future.

Using the empty train station as a central meeting point, the project approached the building by asking how an invisible, violent, and uncomfortable history could both be expressed and then carried away from it. In this context, “giveaways” were used as a strategy to create a shared responsibility for distributing what was hidden and as a way to actively participate in its ongoing narrative. Knowing that the project would be temporary and the structure in which it was housed would be erased, we asked each artist to work directly with the site and make at least one component that could be given away to visitors.

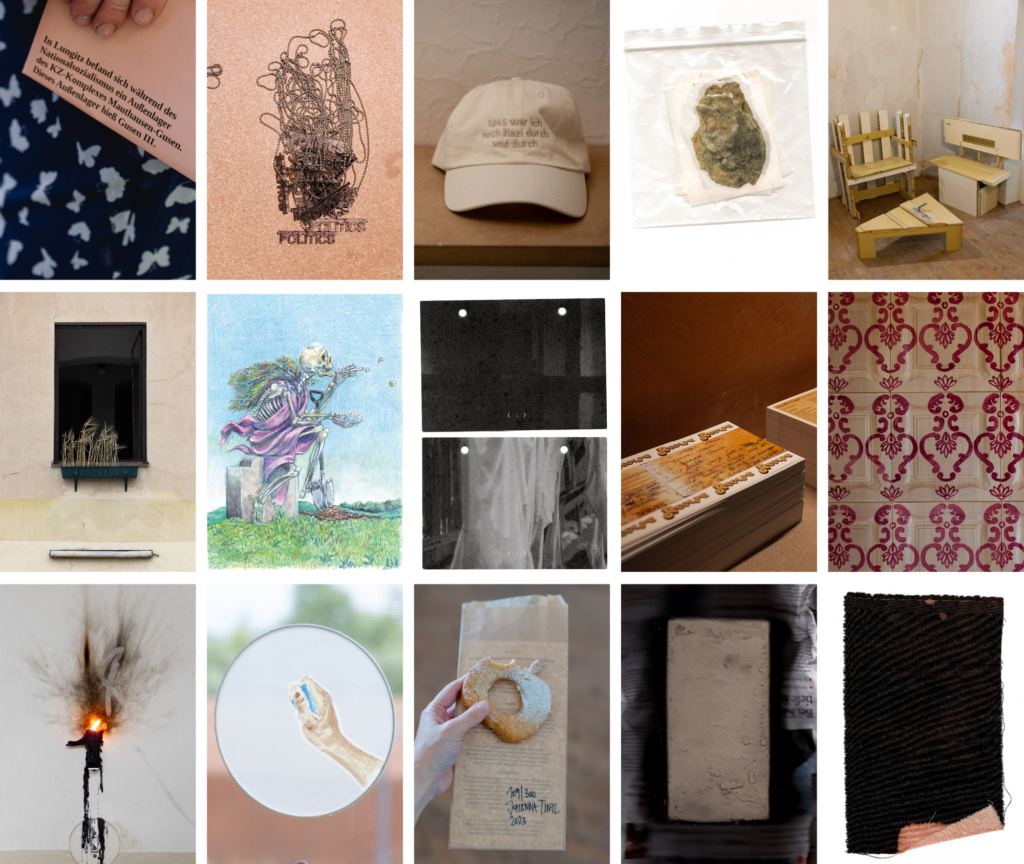

Various Giveaways (Left to Right, Top to Bottom): Seth Weiner, Edgar Lessig, Antoine Turillon, Flo Karl Berger, Anna Weberberger, Marc-Alexandre Dumoulin, Maggessi/Morusiewicz, Julia S. Goodman, Brishty Alam, Stephanie Misa, Abdul Sharif Baruwa, Johanna Tinzl, Baptiste El Baz, Rosabel Rosalind. Most of the artworks changed over the course of FdR, transformed by visitors as they cut pieces away from them, took bites out of them, carried them in their pockets or around their necks, stuck them to light poles, fit them in the trunks of cars, or relayed their experiences to others. One visitor talked about the giveaways finally making sense once they were at home, when they laid some of them out on their kitchen table and walked their flatmate through a guided tour of the project. Photos: Antoine Turillon, Seth Weiner, Flora Fellner, Jürgen Grünwald, esel.at

The first intervention visitors encountered was an exercise in the monumentality of quietness. On the train station’s facade facing the village, all the windows and doors were covered, and three decorative columns were painted to become an abstracted logo of the former Gusen III complex. By muting a single face of the building, our project “Nordfassade (North Facade)” worked to transform the architecture into a signal of its own silence, highlighting the presence of the surroundings and collapsing its distance from the landscape.

Inside the station, Rosabel Rosalind’s Tearing Up invited visitors to participate in an ancient Jewish ritual of mourning called Kriah, where ripping one’s clothing is meant to create an opening to release the heart’s anguish. Staged in the former living quarters of the station, portions of a censored swastika were torn and cut from a piece of bleached fabric to slowly reveal the exterior. Spray-painted swastikas, regularly found as a provocation at sites commemorating the Shoah, are often temporarily censored by being turned into simple line drawings of windows. Alongside the fabric, a giveaway poster offered fifteen satirical ways to revise a swastika ranging from “dudes making out” to a “whirlpool.”

Multiplying this act of mourning through a visual turn of phrase, Stephanie Misa transformed unexpected corners of the train station into altars with An Altar for Unnamed Grief, an edition of black and white candles cast in the shape of chicken feet. Traditionally used in the Philippines and elsewhere as an offering to grant spirits safe crossing into another realm, the chicken foot is an amulet that offers protection and, in Lungitz, a moment of reprieve.

Extending the interplay between inside and outside, Maggessi/Morusiewicz’s Ich sehe ja/nichts (I see yes/no) explored the complexity of choosing “to see” and “not to see” with an installation of sound and film stills from Hasenjagd – Vor lauter Feigheit gibt es kein Erbarmen (1994), a dramatization of the events surrounding a Nazi war crime that took place near Linz just before the end of the Second World War.5 Placed in a room with its windows covered, the collaged soundtrack created an illusionistic sense of the exterior, where visitors could interrupt and rearrange the storyline by taking film stills with them.

In a room across the hall with an unobstructed view to the landscape, Marc-Alexandre Dumoulin explored drawing and the act of looking as an empathic medium. After hiking between Mauthausen and nearby satellite concentration camps, Dumoulin stopped to draw the view from the camps and quarries where inmates were forced to work until they collapsed. Wanting to “see what they saw,” the resulting edition of postcards, Views from the Region, embodies the confusion of being in the local landscape; one side is pastoral and unassuming, while the other, simply by naming the view, points to its history of violence.

Arguing with their own biography, Flo Karl Berger echoed the never-ending process of deconstructing and reconstructing history with their project Karl – ich bin kein nazi aber, mein Vater war keiner aber, mein Großvater war einer aber (Karl – I’m not a nazi but, my father wasn’t but, my grandfather was but) by building furniture from the train station’s doors. Moving between individual and collective social propositions, these pieces of furniture were transported on the train or taken home by visitors in the trunks of their cars.

Extending the act of dismantling and giving portions of the building away, Brishty Alam used decorative ceiling panels stripped from the former living quarters to create a flocked mural that slowly became fragmented as visitors took parts of it with them. Referencing memories of restaurant decor from where Alam grew up, Ruby Murray transposed an imaginary cultural aesthetic from London onto the fading domestic interior of the train station.

Blurring the boundary between intervention and the ready-made, Abdul Sharif Oluwafemi Baruwa worked with a former bedroom using various sculptures, images, sketches, and notations. At times receding into the texture of the room, the installation Missing Link slowed viewers down as they were invited to excavate and trace the room with their senses. A meditation on materiality, memory, and voids, each discrete piece worked toward relating to a whole while remaining individual and fragmented. A missing link was offered to the public in the form of a colorful plaster talisman, a material connection that fits perfectly between the thumb and index finger: “To pass on, to hold, to feel and to heal. A bridge to overcome the gap and collective trauma caused by the mechanisms of racism.”

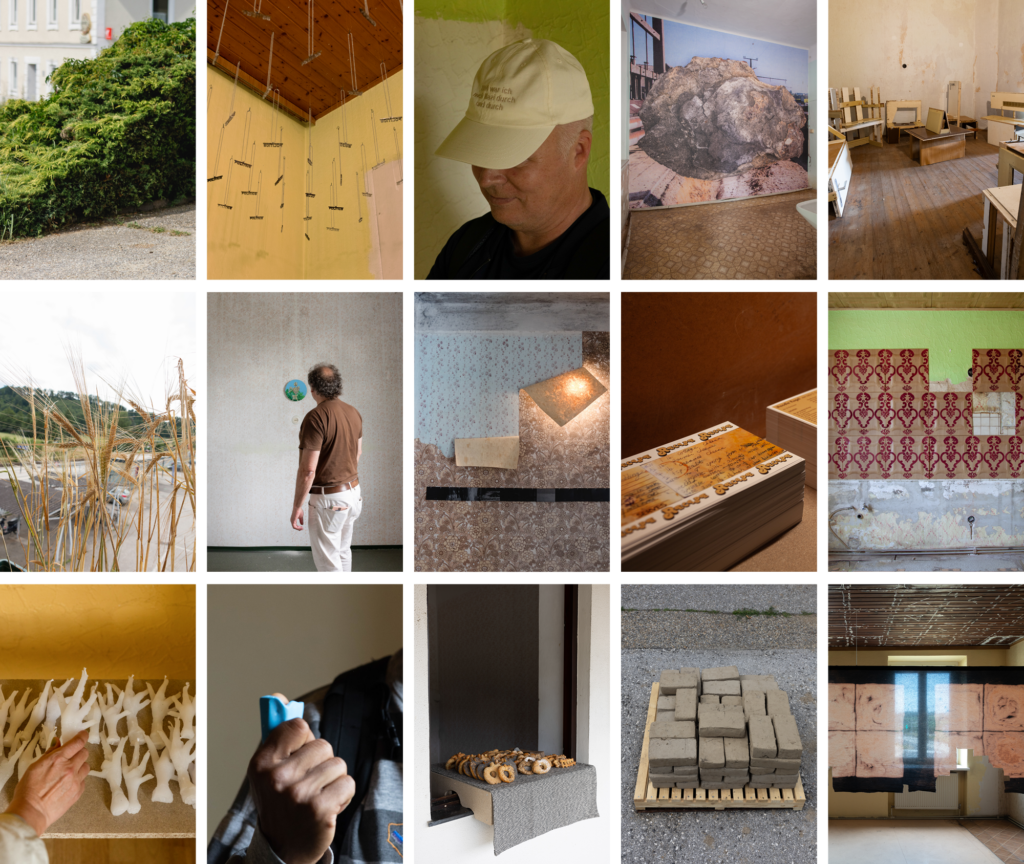

Installation views (Left to Right, Top to Bottom): Seth Weiner, Edgar Lessig, Antoine Turillon, Flo Karl Berger, Anna Weberberger, Marc-Alexandre Dumoulin, Maggessi/Morusiewicz, Julia S. Goodman, Brishty Alam, Stephanie Misa, Abdul Sharif Baruwa, Johanna Tinzl, Baptiste El Baz, Rosabel Rosalind. Photos: Antoine Turillon, Seth Weiner, Flora Fellner, Jürgen Grünwald, esel.at

Offering a controversial statement on wearable baseball caps, Edgar Lessig challenged visitors to confront the regional history. Embroidered with a quote from Lessig’s partner’s grandfather, who said in his advancing dementia, “1945 war ich noch Nazi durch und durch (In 1945 I was still a Nazi through and through).” The hats were given away with the artist’s statement: “I would prefer not to have the hats in my artistic portfolio, but it doesn’t help to pretend they don’t exist either.” At the end of the exhibition, all five hats had been taken.

In contrast to this confrontation, Julia S. Goodman reintroduced a recipe for a common Ashkenazi Noodle Kugel dish from her Grandma Trudy. Translated from English into German and modified to use regional ingredients, the recipe signaled a sense of optimism against a backdrop of vanishing and even lost traditions.

Collaborating with a local baking school, Johanna Tinzl gave away bits and pieces of oral history in the form of bread. The freshly baked rolls were formed into An Apple, a Singing Mouth and the Railroad Tracks, shapes that corresponded to the memories of a resident who was ten years old at the time of the war. Symbolic of the relationship between the prisoners and locals in Lungitz, the bread was given away with prints of the stories, not only referencing the former bakery that serviced the concentration camps but also encouraging visitors to deal with local oral histories that are often carried around in silence but rarely shared with outsiders.

Moving between anecdote and fashion accessory, Seth Weiner’s Club Politics consisted of a series of necklaces made from dirt and glitter with either the word “club” or “politics” on them. Accompanying the necklaces was a small booklet, made in collaboration with his son, in which Weiner describes the process of explaining the Holocaust to him when he was six years old. The short vignette illustrates how trauma is passed along through generations, showing, in effect, the role that fear plays in constructing a sense of belonging.

With a palette of stacked bricks, Baptiste El Baz asked how much the soil remembers. Made from dirt, seeds, and other plant matter from the site of the former Gusen III concentration camp, the seed bricks playfully mimicked guerrilla gardening techniques. A heavy but compact ecological imprint of the site, Seed Bricks – Gusen III allows invisible layers to continue to exist wherever they’re thrown or left to bloom.

Also working with plant matter, Anna Weberberger’s intervention Erd & (Earth &) perverted the Austrian tradition of decorative balcony flowers by cultivating wheat stalks pulled from the fields where the Gusen III concentration camp once stood. Viewed from inside the station through the only window facing the memorial, the wheat brought the site of the former concentration camp into the foreground, collapsing its distance. Viewed from the outside, Erd & marked the station as stubbornly resisting the process of leveling history.

Using the discovery of the remains in the station as a starting point, Antoine Turillon’s installation Unseen #46 (Claudia) rendered visible what was never meant to be publicly displayed. In the room adjacent to where the bags of slag were left, a wallpaper installation displayed an image of the excavations covered by a monumentally scaled piece of slag. Obscuring the excavation, the wallpaper addressed how history is written and rewritten by those who make the decisions.

Walking Tour Map (detail) by Judith Pirkelbauer, Wolfgang Schmutz, Antoine Turillon, and Seth Weiner. Design: Anna Weberberger. Edition of 2000. Tour stops included (1) Lungitz Train Station (2) Village Inn (3) Farmhouses (4) Brick Factory (5) Village Overview (6) Gusen III Concentration Camp (7) Memorial and Gravesite and (8) Remains. Developed as a self-guided tour, maps were given away in the waiting room of the Lungitz train station which encouraged visitors to walk the surrounding area, using the map to call attention to key landmarks that hide in plain sight. The map combines current satellite images, a plan and the only existing photograph of the Gusen III Concentration Camp. After the festival, the map was made available at the Bewusstseinsregion, a local human rights organization in Upper Austria.

Furnished with a wooden bench and a bulky formica table in its center, the waiting room of the train station was the last reminder of the building’s purpose. Used as the first point of contact between the public and the project, a map of the area, developed in collaboration with the historians Wolfgang Schmutz and Judith Pirklbauer, was given away. An overlay of what has been erased, the map guided visitors through Lungitz, providing knowledge and anecdotes about its past and what daily life in and around the concentration camp might have been like. Beginning at the train station, the tour went in a loop past farms to the former brick factory, the bakery, the Gusen III concentration camp memorial, and the grave containing the ash found in 2018. The last stop led visitors back to the train station, to the room where the bags of remains had been left, to reflect on the fact that the building would soon be demolished.

View of the train station from the platform. Photo: Jürgen Grünwald

After ten days of intense exchange and tours, we handed back the key to the building and left the Lungitz Station once and for all. All the works had been taken down and almost every trace of our presence had been erased, as if it had never happened. As outsiders, it wasn’t our place to occupy the space for an indefinite time frame. So when we heard that the ÖBB (Austrian Railway Company) proposed to leave the intervention on the facade of the building as is, without actually returning it to its original state as agreed, the project took an unexpected last turn, marking it as a monument that will continue to point to the past until the building is demolished, the last bags of remains disappearing with it.

As artists, we’re aware of the impossible task of finding an adequate form to express the magnitude of loss that occurred around Lungitz and the persistent forms of violence that we as humans breed. Every email, every document, walk, and encounter, seemed to reveal something unexpected. Something terrifying, informative, and sometimes even uplifting. These unexpected reveals made it especially strange to work on a project for a festival meant to celebrate the region. Nevertheless, we felt the need to try, because it seems today that only through constantly examining the past can we allow ourselves to project a different future.

The authors would like to thank Andrea Wahl, Andreas Haider, Annalise Podor, Felix Vierlinger, Fina Esslinger, Judith Pirklbauer, Laura Rumpl, Otto Tremetzberger, Tomiris Dmitrievskikh, Wolgang Schmutz, and the FdR team for their generous support, patience, and help in making the project possible.

Footnotes

- Built at the end of the nineteenth century, the ÖBB Lungitz train station was used as both a residence and a technical space for the operation of the train. Since 2017, it has slowly been emptied and decommissioned.

- “Menschliche Überreste bei Bauarbeiten am Bahnhof Lungitz gefunden,” OTS, October 14, 2018. [link]

- Located 20 kilometers from Linz (the capital city of Upper Austria) and 8 kilometers from Lungitz, the Mauthausen concentration camp existed from August 8, 1938 until its dissolution on May 5, 1945. Around 200,000 people were imprisoned in the camp and its subcamps, in which more than 100,000 died. More information available at: https://www.mauthausen-memorial.org/en.

- In 2020, the new memorial was unveiled to provide a burial site for victims of the Mauthausen concentration camp. The number, nationalities, and names of the victims are not known. The memorial sits next to the Lungitz/Gusen III concentration camp memorial stone, which was erected in 2000. More information (in German) available at: https://bmi.gv.at/news.aspx?id=78486947473379655734453D.

- “The film’s original title translates as ‘Rabbit chase – for sheer cowardice, there is no mercy,’ a reference to the name given by the SS to the manhunt for the hundreds of prisoners who managed to escape from Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp. Nearly 500 tried to escape, over 300 made it to the nearby woods, and of those, just 11 managed to survive the three months until the war ended.” “The Quality of Mercy (film),” Wikipedia, last modified August 4, 2022. [link]

Antoine Turillon is an artist whose works are mostly created in public spaces, often in collaborative and site-specific approaches. By questioning traditional forms of representation, Turillon’s work creates spaces for social processes that allow for a deeper understanding of the challenges of our time and new ways of understanding and perceiving them.

Seth Weiner’s work employs a wide range of media in which he explores the gaps between architectural fiction and social convention to create both actual and imagined spatial environments. As the Artistic Director of Palais des Beaux Arts Wien, a nonprofit that serves as a mobile place of remembrance and projection for what was lost during National Socialism, Weiner’s work functions as an ongoing act of reclamation and a way to explore what his Jewish identity means in contemporary Austria.