Insurgent Political Theater: Subjects-in-Revolt in Colombia and Palestine

Beatriz E. Balanta and Noah Simblist

August 2022

Protests are one of the basic building blocks of the political grammar of the oppressed. Protests erupt and die down; they are raucous and powerful rivers of people chanting, yelling, demanding. Following the confluence of protests in Palestine and Colombia in spring 2021, we were struck by the images that circulated about them. We asked ourselves: Is there something similar about these protests or at least their representation? Can we discern an aesthetic taxonomy of the protests in Palestine and Colombia?

On the one hand, there are the manifestations of rage against the machine we have come to expect: burning tires, flags, signs and banners, or photographs of the dead. On the other hand, there are protest tactics that subvert the normative expectations of forms of revolt: fire breathers, cosplay, and voguing in front of the armored agents of the state. Protests are theatrical performances, orchestrated for a variety of audiences – fellow subjects in distress, such as the oppressor or the ally. Given that protests are multivalent and culturally specific, we ask: What were the political and, more importantly, the sentimental objectives of performances staged by subjects-in-revolt1 in Colombia and Palestine in spring 2021?

But first, we would like to lay out our relationships to these places and the ways that we have each encountered protest on the ground.

Beatriz Balanta: I grew up in Colombia, but I have spent most of my adult life between Colombia and the United States. After years of helping organize and participating in protests in both countries, I have come to fear them. When protests erupt, I cannot help but think to myself: “What is the point? They will kill you.”

Noah Simblist: I have spent a great deal of time in Israel-Palestine over the course of my life. I grew up in Jewish and Zionist communities in the US and Europe but spent most summers in “the holy land” as a child, eventually living in Jerusalem for some time as an adult. As I became secular and my politics shifted towards Palestinian solidarity, I focused my work as an artist, writer, and curator on the political tensions of the region. Through this process, I have witnessed and participated in a number of protests there.

We are writing this collaboratively, based on a long history of teaching and working together. For many years, we wondered about the similarities and differences between these two places that we know intimately.

Indigenous Rising Instagram post, May 14, 2021.

Where Necropolitics Converge

What is it about the aesthetics of protest in Colombia and Palestine that compels us to bring them together in analysis? Both countries have a history of extreme state violence and popular resistance, but there is also a more direct relationship. Palestine under occupation has been designed by the Israeli government as a space of intense colonial violence and as a macabre lab. It is a place where Israel invents, develops, and tests its military products before selling technologies of death to the highest bidder.2 In the 1980s, the Israeli government sold the Guatemalan right-wing military junta sophisticated communication and computer technology that allowed the tracking, kidnapping, and ultimately murder of leftwing “subersivos.”3 During Argentina’s guerra sucia, Israel provided sophisticated weapons to the Argentinian state, including missiles, missile-alert radar systems, and anti-tank mines. In his 2001 autobiography, Carlos Castaño, one of the founders of the Auto-Defensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) – an umbrella organization of the Colombian armed right wing, or paramilitares – disclosed that he spent more than a year (1984–1985) training in Israeli military schools and Hebrew University. Castaño also revealed that he had copied his idea of “autodefensa,” distributing guns to a chosen group of people to defend a cause, from the Israelis, a country where, according to Castaño, “every citizen is a potential soldier.”4 In 2010, Colombia bought Israeli drones for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). These drones were tested in Gaza in 2008 and 2009 during Operation Cast Lead.

The Protests of Spring 2021

While the political and military elites of Israel and Latin America pride themselves in their collusion to collaboratively develop transnational murderous connections, at the same time, there have been multiple declarations of solidarity among insurgents. In Spring 2021, this was amplified by the simultaneous eruption of protest in both regions. In Palestine, following the demolition and occupation of Palestinian homes by Israelis in Sheikh Jarrah, protests and violent crackdowns grew in Jerusalem’s old city, including at the Muslim holy site of Haram al-Sharif. In response to this Israeli aggression, Hamas launched rockets and Israel responded with airstrikes in Gaza that leveled entire city blocks. The confrontation killed more than 250 Palestinians and over a dozen Israelis.

In Colombia, protests erupted around the same time. A twenty-four-hour national strike was called for by the Unified National Command (a coalition of labor unions), the General Confederation of Workers (CGT), the Workers Confederation of Colombia (CTC), the Education Workers Federation (FECODE), and the Confederations of Retired Workers (CPC and CDP). The government of Iván Duque reacted with extreme violence, which ignited the protests that began on April 28 and prolonged the strike, which lasted for more than a month.

Where Histories Diverge

While there are intersecting histories for Colombia and Palestine, they also diverge in a number of important ways. First, Colombia, as a modern nation-state, began as a Spanish colony in 1525, a process that included the expropriation of land, the subjugation of Indigenous populations, an influx of kidnapped and enslaved people from Africa, and the establishment of an economic system based on extraction economies. Like many other parts of Latin America, the anti-colonial independence movement gave way to a new nation-state, but many of the oppressive anti-Black and anti-Indigenous sentiments and socio-economic structures of the colonial regime remain to this day. Colombia is a sovereign state that exists in a constant battle with colonial ghosts.

Palestine, on the other hand, has a history going back thousands of years with cycles of sovereignty that have allowed various degrees of self-determination by its local population. While there is a history of Palestinian nationalism that emerged during the late Ottoman period, through the post-WWI British mandate, and continues to this day,5 Palestinians have been stripped of sovereignty, and since 1948 survive under what Achille Mbembe has characterized as a “necropolitical” colonial regime. According to Mbembe, Israel is a state that deploys its weaponry (bombs, checkpoints, land expropriation, etc.) “in the interest of maximum destruction of persons and the creati[on] of death-worlds, new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead.”6 Mbembe observes that the Israeli model of colonial occupation is transacted through a combination of territorial fragmentation, vertical sovereignty, and splintering occupation, which results in the absolute domination over the inhabitants of the occupied territory.7

When thinking about the histories of Colombia and Palestine, and specifically, what we are calling the insurgent forces within these territories, we must also compare the particular forms of organized resistance in these places. The Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), founded in 1964, is the most prominent insurgency in the case of Israel-Palestine. Splinter groups such as Black September, the al-Aqsa Martyr’s Brigade, or Palestinian Islamic Jihad have all engaged with political violence, both in Israel-Palestine and globally. Hamas is a newer group that functions as a political party engaged in armed struggle and governance, primarily in Gaza. After the Oslo Accords in the 1990s, the PLO’s largest faction, Fatah, emerged as the political party that governs the quasi-state of the West Bank under the moniker of the Palestinian Authority. But the Palestinian insurgents that we are referring to, who engaged in the protests of spring 2021, were not, by and large, driven by any of these organizations’ violent or political resistance. Rather, they were grassroots reactions, on the streets, to particular instances of Israeli occupation.

In Colombia, insurgencies such as M19, FARC, and ELN all have their particular histories. Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), like the PLO, was also established in 1964. The FARC is Latin America’s oldest and largest guerrilla group of leftist and peasant origins. It should be noted that the FARC emerged as a predominantly rural structure of the Colombian Communist Party (PCC). Beginning in the 1920s, peasants began to organize against harsh working conditions in plantations managed by multinational corporations such as the United Fruit Company, struggles to gain land titles, and the struggles of Indigenous people to regain control of lands they lost due to a violent program of expropriation led by the state and elite-funded militias. By the 1960s, a series of episodes of political violence, the murder of political leaders, the continued exploitation and killing of peasants, and the flourishing of socialism and communism created the conditions for the emergence of different armed insurgent groups, including the FARC.

Similar to Palestine, Colombia remains – even after going through a few peace agreements – a nation at war. Like Palestine, one of the issues that fuels the war in Colombia is over control of land. In Colombia, it is calculated that a little more than 10,000 landowners own about 67 percent of the most fertile land. This accumulation of land by a small elite was achieved by the systematic dispossession and forceful displacement of millions of people that began in the colonial period and has exacerbated over the last sixty years. In recent decades, other actors have increasingly joined the fray: financial institutions and international speculators, crime syndicates, militias, and guerrilla groups fuel a conflict that taints everyday rural life in Colombia with the metallic taste of blood.

Palestine Spring 2021

The fundamental issue at stake for protests in Palestine in spring 2021 goes back to key moments in the occupation of Palestine in 1948 and 1967. While this history is too complex to go into here, the protests that emerged in this latest flare-up were tied to these grievances. The resistance to the occupation is also an advocacy for sovereignty and human rights, both of which were at stake with the demolition and occupation of homes in Sheikh Jarrah, which had increased significantly in 2021. Further compounding this are the religious stakes. Sheikh Jarrah is in East Jerusalem, a holy city in Islam, Judaism, and Christianity. Because Israel has defined itself as a Jewish state, it wants to solidify control over this symbolic site. The expulsion of Palestinians from their homes in Jerusalem is often carried out by Jewish Israeli civilians in collusion with the Jewish state of Israel that legally, politically, and militarily backs them up.8 The state of Israel has an interest in Judaizing Jerusalem through a process that pushes Palestinians out. Thus, each overt incursion into areas of Jerusalem is perceived by Muslim and Christian Palestinians as an attack on both religious and national sovereignty.

The culmination of a series of violent Israeli crackdowns on Palestinians protesting the land confiscation and housing demolitions in Sheikh Jarrah was an Israeli military incursion of the Muslim holy site Haram al-Sharif during Ramadan prayers. This was followed by regular clashes between the Israeli military and Palestinian protesters at the Damascus Gate. Eventually, Hamas, which controls Gaza, responded to this situation with rocket attacks from Gaza into Israel. This was met with an Israeli response that included a brutal bombing campaign until a ceasefire was declared on May 21, 2021.9

Colombia in Spring 2021

In Colombia, the most recent wave of protests came after the Colombian government and the FARC signed a peace agreement after three years of negotiations. The 2016 Peace Accords promised the most ambitious transformation of Colombia’s countryside in the nation’s history, through a flagship project named the Development Program with Territorial Focus.10 The program aims to improve infrastructure and provide drinkable water, electricity, healthcare, and education to rural areas of the country that had been the most affected by violence. Land reform, reparations for victims, and the re-incorporation of ex-combatants into civil life are some of its most important components. Today, peace remains elusive in Colombia and extreme social inequality is the norm.

In April 2021, a national strike paralyzed Colombia. The anti-government demonstrations were called for by labor unions, Black and Indigenous groups, peace activists, and NGOs representing victims of the armed conflict to protest against a series of proposed tax and fiscal reforms organized under the moniker Ley de Solidaridad Sostenible (Law of Sustainable Solidarity). The protests quickly became a collective outlet for pent-up grievances against Colombia’s economic policies and political elite: increased levels of violence against civil rights activists, the failure of the 2016 Peace Accords, increased levels of socio-economic inequality in the second most unequal country in Latin America, and the continued displacement of peasants to clear the way for the extraction of natural resources, agricultural projects, and drug trafficking. In 2016, Colombia had one of the world’s highest numbers of internally displaced persons (IDPs), which amounted to about six million people.11

While the particular histories and contemporary triggers for the most recent flare-ups in Colombia and Palestine were different, both were situations in which disenfranchised people expressed their frustration at state powers. Also, in both places, the pandemic had aggravated already precarious economic, social, and political conditions. Furthermore, social media and the slower pace of life under the pandemic allowed for grievances to be shared and protests to be organized, and images of the state violently cracking down on protesters circulated quickly so that the cycles of protest and counterprotest measures grew exponentially in both regions.

Contemporary Palestinian-Colombian Solidarity Efforts

In April 2021, a “Week Against Apartheid” conference was organized by the Latin American contingent of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement that brought together activists from Palestine and Colombia as well as panelists from Chile, Argentina, and Peru. The focus was on the Covid pandemic and the ways in which it has further revealed various forms of subjugation in these contexts.12

Sofia Garzón, a social activist who works at Proceso de Comunidades Negras (PCN), talked about the need for solidarity between not just Colombians but specifically Black Colombians and Palestinians. She described a situation during the pandemic that revealed structural racism and classism in the healthcare system. She also discussed the military structure of Colombian society and the ways in which the pandemic expanded the systems of control through martial law and limitations of movement. Garzón referred to this as the necropolitics of Covid management.

Qassam Muaddi, a Palestinian journalist based in Ramallah who has also worked in the nonprofit sector, described a similar situation in Palestine. First, in terms of healthcare, he described a double standard. Israel received world renown for quickly acquiring vaccines and inoculating its population, even to the extent of offering one or more boosters to its citizens on top of the initial two shots. But Palestinians did not have the same access to vaccines and had a much lower rate of inoculation. Muaddi then addressed how the pandemic had interrupted informal economies – the most prevalent form of employment for Palestinians. Prior to the pandemic, many worked in restaurants or hotels in Israel or in West Bank settlements, but once the lockdown occurred, they no longer had access to these jobs. This continued even after Israelis were able to move back into these sectors. Because of the lack of Palestinian vaccination, these workers weren’t able to return to work. Others who worked in construction in these areas were forced into a difficult choice. Israel didn’t want unvaccinated Palestinians moving back and forth across the border, so they could either work at a construction site and live there under precarious conditions or they could stay at home with no work.

The “Week Against Apartheid” conference was a contemporary example of solidarity between Colombians and Palestinians that gave voice to the shared frustrations that would lead to, just a few weeks later, the protests that exploded on the streets of both regions.

Visual Representations of Protest in Colombia and Palestine

When the first major Palestinian protests against the Israeli occupation erupted in 1987, rock throwing, burning tires, and teargas became conventional tropes in the global media. These elements have remained the basic structure of protests in Palestine. Politics can be defined, among other things, as a series of performances designed to mobilize a bunch of affective states to incite people to act in certain ways. This is what binds both those in power and minoritarian struggles against hegemony. While tactically, Palestinian protesters during the First Intifada might have been expressing immediate anger and frustration at the soldiers that confronted them or even a form of civil disobedience that slowed down the machine of sovereign power, strategically there was also an awareness of the power of representation. A protest held the possibility of being represented in the media. The target of Palestinian activists’ protest when they filled the streets was not the soldiers at the end of the road, nor was it their generals or even Israeli civilian politicians. The target was world opinion, and in the mid-1990s, with the Oslo Accords, there was some hope that this strategy was paying off. But this performance became so common that it lasted throughout an unending occupation, as the Oslo Accords failed to bring about Palestinian sovereignty and even basic human rights. And when Palestinian protesters used the same tactics, the global media was less likely to pay attention. By the time the Second Intifada began in 2000, activists started to use new tactics, emphasizing the obvious performativity of the act of protest.

Let’s first compare two quintessential images in which a solitary protestor faces off against the military. One is in Colombia, the other is in Palestine. We notice that in both images, the street has been emptied of traffic and has been divided between the military and the protesters. In both cases, a lone protestor throws something toward the soldiers. In both cases, their faces are hidden to potentially protect their identities but also to cover their mouths from teargas or smoke. In Colombia, the figure is throwing back a tear gas canister. The protester seems to be part of a larger group, as we can see signs of others at the margins. In both cases, the agitation is not only seen through the lack of traffic but also the street filling up with smoke.

Both in Palestine and Colombia, it is a military tactic to use water cannons. Water is weaponized and yet described by the cannon’s designers as an allegedly less violent form of crowd control, at least compared to bullets or the brute force of a baton. Yet, the force of these water cannons is so powerful and violent that they are used to clear populations out of the streets. In Israel, they are sometimes filled with a noxious substance that compounds the physical power of the water with a repellent smell. This weapon is referred to as “skunk.”

Palestinian youth perform fire-breathing at the ruins of a building destroyed in recent Israeli air strikes in Beit Lahia in the northern Gaza Strip on May 26, 2021. Photo: Mohammed Zaanoun/Activestills

In contrast, Mohammed Zaanoun from the photographic collective Activestills captured a moment in Beit Lahia in the Gaza Strip in which three Palestinian men performed fire breathing on top of the rubble of a destroyed apartment complex. Contrary to the more typical image of the protester as freedom fighter or victim in the face of state power, this rather spectacular carnivalesque moment does something different. In the image, we see these men in black jogging pants, shirtless, astride crumbling concrete, spitting a mist of fuel onto fiery torches, creating the illusion that they are breathing fire. This trick is performed on a sunny day with a clear blue sky. The trick suggests that these men are superhuman, that they are like dragons, that they have magic mythical powers. They imagine an alternate reality to the clear evidence of sheer brutality that serves as the photograph’s backdrop.

Protesters dressed as characters from the movie Avatar take part in a protest in Nilin on February 12, 2010. Photo: Darren Whiteside/Reuters

This image recalls another earlier Palestinian tactic of insurgent political theater in 2010 in which demonstrators dressed as the Na’vi from the 2009 film Avatar. Avatar’s primary narrative includes a human settler colonial force intent on using violence to extract a precious mineral from the Na’vi planet. The Na’vi, tall with blue skin and pointy ears, are depicted as an indigenous community that has a sacred connection to their land, which is disregarded by the colonizers. This part of the narrative is what the Palestinian protesters, marching against the construction of the separation barrier also known as an apartheid wall in Bi’lin in the West Bank, wanted to invoke. Thus, as Palestinian protesters have teargas thrown toward them and as they are dragged, beaten, or shot at by Israeli soldiers, the image circulated in the media is of Israeli soldiers enacting this violence on the Na’vi.13 This is a self-conscious use of photojournalism as a document of protest as political theater.14

By using tactics like the Na’vi stunt, this innovative form of activism created a strange rupture in our expectations, opening up the possibility of asking questions, first and foremost: What’s going on here?15 So, when The Guardian reports on this innovation, it could be reporting on the news of the form of protest. But it also addresses the political issues at stake and potentially moves the sentiment of the viewer so that they might empathize with the Palestinian Na’vi much like they are asked to empathize with the Na’vi in the fictional film.16

Voguing at the Capitol

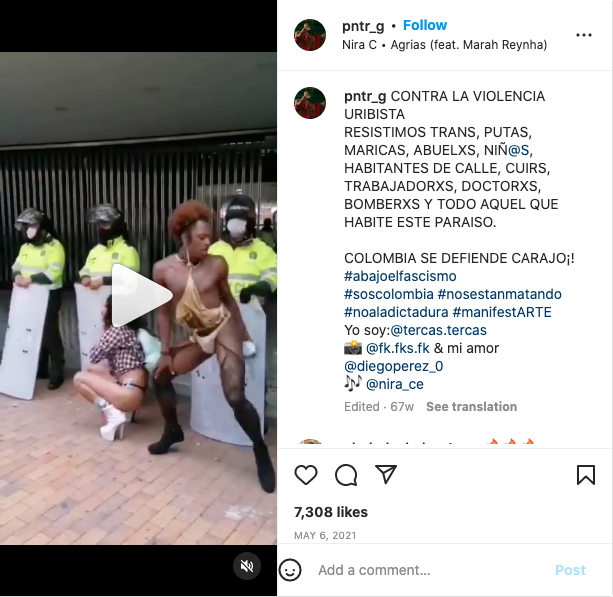

A buttock slides up and down a police shield. The policeman that stands behind the bulwark is frozen while the dancer’s muscular booty caresses, slowly and deliberately, the policeman’s instrument of violence and control. On April 28, 2021, Pantera Godoy, in a light pink man-thong, used contemporary forms of Black dance, twerking and voguing, to protest economic, social, and cultural oppression in Colombia. Later that day, Piisciis, Nova, and Axid vogued at the Plaza Bolívar, the seat of the Colombian government, while other protesters danced to the rhythm of drums. These dance performances became iconic moments in the aesthetics of protest in Colombia. They were also packaged for consumption as news by international media outlets such as the New York Times.

Pantera Instagram post May 6, 2021.

Pantera’s booty shake sexualized the shield, sensualized the act of protest, and positioned the Black-queer-trans-body in dangerously close proximity to an instrument of state terror. A riot shield is a prosthesis and a double-edged sword. It was designed to protect state actors (the police) from projectiles thrown at them by protestors. As such, it embodies the will of the state to protect itself and the status quo. The shield is also a part of an aggressive structure of containment. Kettling, the police tactic of surrounding protestors to corral them in place or to move the crowd to particular places, is an example of how riot gear – including helmets, batons, shields, knee pads, and groin protectors – is part of a machinery created to squash the actions and dreams of insurgent subjects fighting against the necropolitics of the state.

The buttocks are a wall as well – a shield for the anus, an aperture of vulnerability. The anus is the site of the entanglement of pleasure and pain, and when the buttocks bounce around it, they vibrate to illuminate its aura. In making the shield part of the dance performance, Pantera inserts this violent object into a different logic of power and signification. Pantera transforms it into a toy, a sex toy, an object of enjoyment. Given the history of police violence against racialized bodies coded as sexually deviant, Pantera’s bootylicious play with this violent gadget is a daring act of defiance. In Colombia, as in many other places, police torture queer people through sexual violations that very often include the forceful introduction of batons, guns, and other objects into the anus. In this context, Pantera’s performative gesture – rimming the shield, as it were – destabilizes, if only for a moment, the vicious use of the instrument.

Besides twerking on the shield, Pantera vogues through the streets of Bogotá. As a creation of Black and Brown queer and trans folks in the United States, voguing has been a way to play, question, and rearrange notions of gender, class, race, and sexuality. It has also been an important strategy for the imagination of radical definitions of family, community, and politics in the Black queer community. Voguing, like twerking and many other African diasporic cultural practices, has been appropriated by the cultural industry. Yet, these embodied performances have not lost their edge as an international language of both joy and resistance – as demonstrated by the many performers in different geopolitical locales that center voguing as a performative platform that allows trans and cuir (queer) people to pridefully embrace joy, pleasure, and care.

Protests often take place in the street, parks, and plazas; they are tight spaces – physically and emotionally. Bodies are close together, while excitement, fear of death, and hope are grafted on the space between each other’s skin. In this high-tension space, acts of performance such as Pantera’s breathe political life into disposable lives (Black, queer, impoverished, displaced, humiliated). In these moments where insurgent energy is channeled through an incantation of the body, resistance is not about changing the life circumstances of the oppressed, nor is it about the destruction of a system of oppression. These theatrical performances of insurgent political energy crack the unyielding space of oppression and produce a fissure in the overwhelming logic of domination. In Colombia, a place where the Black queer body is perceived as infected, contaminated, expendable, and subject to torture, these moments of political performance where the dancer seizes the moment and through their body enacts a radical vulnerability while reveling in the carnal, curtail, if only for a brief period, the flow of bloody power.

In one sense, the logic of the Palestinians dressing as the Na’vi is dressing in drag. One could say that they are dressing as the other, but in essence, they are dressing as themselves – performing themselves more fully. This is the politics of disidentification, as José Esteban Muñoz brilliantly argued in Disidentification: Queers of Color and the Politics of Performance (1999).17 Muñoz built on theories of the performance of subjectivity that centered on intersectional queer and feminist politics, but we’re interested in the ways in which the performance of politics can be thought of more broadly and might even be brought to bear on these two situations in spring 2021.

Conclusion: Insurgent Political Theater – The Performance of Politics

Pantera’s bootylicious intervention was an uncanny carnivalesque moment that, like the Na’vi apparition in the West Bank, invited joyful laughter, a flow of life that can change the energy of the crowd. As activist and photographer Oscar Diaz said about the queer and trans Colombian protesters, “We’re undeterred in creating a world where we can radiate joy, share abundance and pleasure, and insist on an economy of care for each other.”18 The carnivalesque has been a constant in political performance. The Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin defines the carnivalesque as a surreal space where normally unacceptable behavior in a civic space is invited, when hierarchies are mixed up, where heaven and hell, high and low, sacred and profane exist at the same time and normative orders are challenged. Bakhtin says, “carnival is a pageant without footlights and without a division into performers and spectators. In carnival everyone communes in the carnival act . . . all distance between people is suspended, and a special carnival category goes into effect, free and familiar contact between people.”19 We might think of Carnival in Rio de Janeiro or Mardis Gras in New Orleans, where costumes, music, dance, and adornment mix to provide an unbridled sense of celebration. This particular affective mode in public space has become important for protesters – like the puppets and pageantry of the 1999 WTO protests – to counter the perception of anger being the primary affective modality of the insurgent. The carnivalesque is an aesthetic and affective mode that, as Bakhtin points out, invites us to challenge the expectations of normative civic life, including the assumed immovable power of the state and the status quo.

“We’re undeterred in creating a world where we can radiate joy, share abundance and pleasure, and insist on an economy of care for each other.” —Oscar Diaz

When the status quo in Colombia and Palestine includes systemic disenfranchisement and when the utterance of protest against this hegemonic control is so often met with violent crackdown, it makes sense that the insurgents might adapt.

The moment when Pantera twerked on the policeman’s shield was, like many other improvised moments in political performances, a radical moment of undecidability. This action was unplanned and contingent on the context. At the same time, Pantera performed a vulnerability that already exists. As a Black trans performer confronting the police and risking their safety in the public sphere, they performed an all too common precarity. But can we also imagine this as a call-out? A dancer on the floor, voguing, twerking, and performing their best, awaiting the next dancer to take the stage? Ideally, this would also be a call-out to the people of privilege to place themselves in radical vulnerability as an intervention in the system of oppression.

A call-out like this is simultaneously utopian and absurd. Contemporary political performances embody the absurd because they seem so radically different from the status quo. New forms of confrontation are demanded because new conditions of being are demanded. Both the demand and the performative form in which the demand is made seem absurd, but that is because they have yet to become folded into our contemporary reality. As Muñoz has argued, queerness is not yet here, it is a condition of a utopian future – something that sits on the horizon, seen but not yet felt.20 For us, queerness can be expanded to various forms of Colombian and Palestinian identity that have yet to achieve sovereignty, freedom, and self-determination. The call-out, as we imagine Pantera’s performance or even the Palestinian fire breathers to be sending, is a call to a future – a different future in which those rights are achieved.

Performativity is an expression of one’s self but also one’s self in the public sphere. The performance of subjectivity in the public sphere is an important mechanism for the citizen subject to negotiate their marginalization in relation to state structures that have historically acted against the very possibility of their existence. The objective of political theater is to activate a subversive subject – to appeal for the potential for subversive ideological positions and bodies to become a part of the public sphere and thus of a civic structure.21

Postscript: Back to Business as Usual

The Na’vi protesters in the West Bank and the twerking queer folk in the streets of Bogotá represent a rupture in the fabric of normative activism. But the shimmer of affect that they provide is a tributary to the flow of the raging river of history. The fact is that after these mesmerizing, carnivalesque performances of protest, the status quo remained intact. Or did it?

In Israel, a brutal occupation has continued; the wall that protesters sought to remove was built anyway. In the spring of 2021, hundreds of precision-guided bombs and missiles rained on Gaza. The result: at least 248 people dead, including 66 children, with more than 1,900 people wounded from Israeli air and artillery attacks.22 Following the attack on Gaza, there was a ceasefire, but in August 2021, Israel bombed Gaza in retaliation for incendiary balloons launched over the border. In September, Israel shot five Palestinians in the West Bank while the US Congress voted overwhelmingly to fund an Iron Dome missile shield with $1 billion in addition to the $3.8 billion that the US annually gives Israel in military aid. Recently, in the spring of 2022, Al-Aqsa once again became a site of violence.

In Colombia, the protests seem to have had deep repercussions in the political field. They led to serious conversations about class, inequality, race, and the urban/rural divide, which produced a radical political transformation – the election of Gustavo Petro, a former member of the M-19, as President and Francia Márquez, a Black woman and an environmental activist, as Vice President. In contrast to many other Latin American countries, this is the first time that a leftist government has been elected. Furthermore, Márquez is from a rural, working-class part of the country, displacing traditional structures of power. Yet, this unprecedented event must be analyzed against the state of war that characterizes Colombia’s everyday reality. In 2020, Indepaz reported the murder of 310 social, Indigenous, Afro-Colombian, and peasant leaders, members of the LGBTQI+ community, and 64 signatories of the Peace Accord. So far this year, at least 135 activists have been killed. Meanwhile, Colombia continues to have the highest number of internally displaced people in the world: 7.2 million people, most of whom are peasants of Indigenous and African descent, are pushed off their land at gunpoint so that we may continue to live on the spoils of conquest and colonialism – gold, silver, coal, oil, water, beef, CBD oil, and, let’s not forget, the exotic bouquet of flowers available at Whole Foods for $15.99.

We return to this history of violence because we are suspicious of gestures towards transcendence or redemption in political narratives. One reason for this skepticism is that optimistic, sunny dispositions often characterize the language of those in power touting peace accords and new futures that rarely bear fruit. The harsh realities that the political insurgencies in these two regions revealed once again persist until today and will be the reality in the foreseeable future. But we raise these parallels of protest tactics to propose a speculative future – the further development of alliances and solidarities – that embraces the performative imaginary as a new way of illuminating injustices and advocating for substantial social and political change.

Footnotes

- In this essay, we will be using a number of terms to refer to “subjects-in-revolt.” Terms such as protesters, insurgents, guerillas, and terrorists have been used to refer to these subjects. The choice of words refers to nuances of both the subjects themselves and the ideology of those that are describing them. To some, any protester against the government is a terrorist; to others, any protestor is a freedom fighter, regardless of their ties to organized forms of political resistance. For the purposes of this essay, we are most interested in the protesters on the street and have chosen not to adjudicate their relationships to particular political groups, violent or otherwise.

- This is explored in Yotam Feldman’s 2013 film The Lab.

- Ronaldo Munck and Pablo Pozzi, “Israel, Palestine, and Latin America: Conflictual Relationships,” Latin American Perspectives 226, vol. 46, no. 3 (May 2019): 4–12. See also, Les W. Field, “The Colombia-Israeli Nexus: Toward Historical and Analytic Contexts,” Latin American Research Review 52, no. 4 (2017): 639–53.

- Mauricio Aranguren Molina, Mi confesión: Carlos Castaño revela sus secretos (Bogotá: Editorial Oveja Negra, 2001), 108.

- Rashid Khalidi, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of a Modern National Consciousness (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997).

- Achille Mbembe, “Necropolitics,” Public Culture 15, no. 1 (2003): 40.

- Mbembe, “Necropolitics,” 28–30. For an in-depth discussion on the difference between modern colonial regimes and contemporary forms of colonialism, see Achille Mbembe, On the Postcolony (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

- This relationship between civilians and the state carrying out the daily practices of occupation is outlined in Rafi Segal and Eyal Weizman, A Civilian Occupation: The Politics of Israeli Architecture (London: Verso, 2003).

- Patrick Kingsley, “After Years of Quiet, Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Exploded. Why Now?,” New York Times, May 15, 2021. Oliver Holmes and Peter Beaumont, “Israeli Police Storm al-Aqsa ahead of Jerusalem Day,” The Guardian, May 10, 2021. “Israel Gaza Ceasefire Holds Despite Jerusalem Clash,” BBC News, May 21, 2021.

- Description of PDET (in Spanish).

- Adriaan Alsema, “Colombia has more internally displaced persons than Syria,” Colombia Reports, June 20, 2016, https://colombiareports.com/colombia-internally-displaced-syria/.

- “Semana Contra el Apartheid en América Latina: Contra el Racismo,” Tadamun Antimili.

- “Avatar Protest at West Bank Barrier,” The Guardian, February 12, 2010.

- See also the 2011 film Five Broken Cameras, which tells the story of Emad Burnatt, a Palestinian activist who documented the weekly protests in Bi’lin.

- Creative forms of protest have a long history throughout the world, beyond this particular example. Groups such as ACT UP have used performative die-ins. A coalition used carnivalesque practices such as puppets during the 1999 WTO protests in Seattle. There is also the standing man tactic used during the 2013 Taksim Square protests in Istanbul, and the numerous creative representations of “the disappeared” in Latin America. We make no claims that the creativity found in these two regions is exceptional, but they allow us to examine two case studies together.

- To be clear, performativity does not negate the earnestness of the protesters’ demand. There have been numerous examples of Israel claiming that certain protests were mere theater or fake news to stir up the street. We are not making this claim, but rather are working under the assumption that all protest is performative.

- José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentification: Queers of Color and the Politics of Performance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

- Sandra Song, “The Trans and Queer Organization Protesting Colombia’s Government,” Paper, May 20, 2021.

- Mikhail Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984), 122–23.

- José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NYU Press, 2009).

- Both Judith Butler and Michael Warner make a similar argument about the politics of public space and public assembly. See Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015) and Michael Warner, Publics and Counterpublics (New York: Zone Books, 2002).

- Khuloud Rabah Sulaiman, “Gaza attacks: Fear, finality, and farewells as bombs rained down,” Al Jazeera, May 22, 2021.

Beatriz E. Balanta (PhD, Duke University) is interested in the intersection between visual culture, politics, and definitions of freedom. She is also curious about contemporary theorizations and art practices from the Global South. She is the founder and director of BlackGround Lab in Cali, Colombia.

Noah Simblist works as a curator, writer, and educator. His dissertation, Digging Through Time: Psychogeographies of Occupation (2015) focused on the ways that contemporary artists in Israel-Palestine and Lebanon address history. Most recently, he edited the book Tania Bruguera: The Francis Effect (Deep Vellum, 2022) and co-edited Commonwealth (Publication Studio, 2022) tied to an exhibition that was co-produced by the Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University, Beta Local, and the Philadelphia Contemporary. He is Associate Professor of Art at Virginia Commonwealth University.