Killing the Dominant Narrative: Geopolitics and Training for the Future

Sumugan Sivanesan

December 2020

Training for the Future was an initiative developed by Studio Jonas Staal in conjunction with the 2019 Ruhr Triennale curated by Florian Malzacher and presented last fall (September 20-22). The “utopian training camp” was held in the impressive Jahrhunderthalle, a former gas powerstation cum Kraftwerk für Kultur set on the edge of Bochum, Germany’s sprawling Westpark. The site of a former steel works, it was revived for recreational and cultural purposes with circular pathways, spiralling bridges and staircases winding around landmark industrial ruins.

Training for the Future follows the New World Summit, an organization founded by Staal to present democratic assemblies for groups often outlawed by nation states, and New Unions which brought together “emancipatory political organizations” from across Europe in a series of campaign events to discuss transnational unionization and democracy. A recurring aspect of Staal’s practice is the staging of emancipatory politics and activist knowledge in contemporary arts settings for which his studio designs sets, furniture and graphics that often reference Constructivist ideas. These events make use of lighting and music; dramatic effects that blur the lines between political gatherings, theatre, happenings and installation.

Arguably, Training for the Future marks a shift in Staal’s oeuvre which often foregrounds ‘speech acts’ in the various campaigns, assemblies and parliaments he has produced, to instead emphasize skill-sharing and embodied, often performative, pedagogical encounters. The sessions deployed methods including collective choreography, presentation and discussion, voice and movement, action and role-playing. Each day concluded with a simple meal, followed by a collective summary and debriefing, which ultimately I found the most insightful.

Togetherness

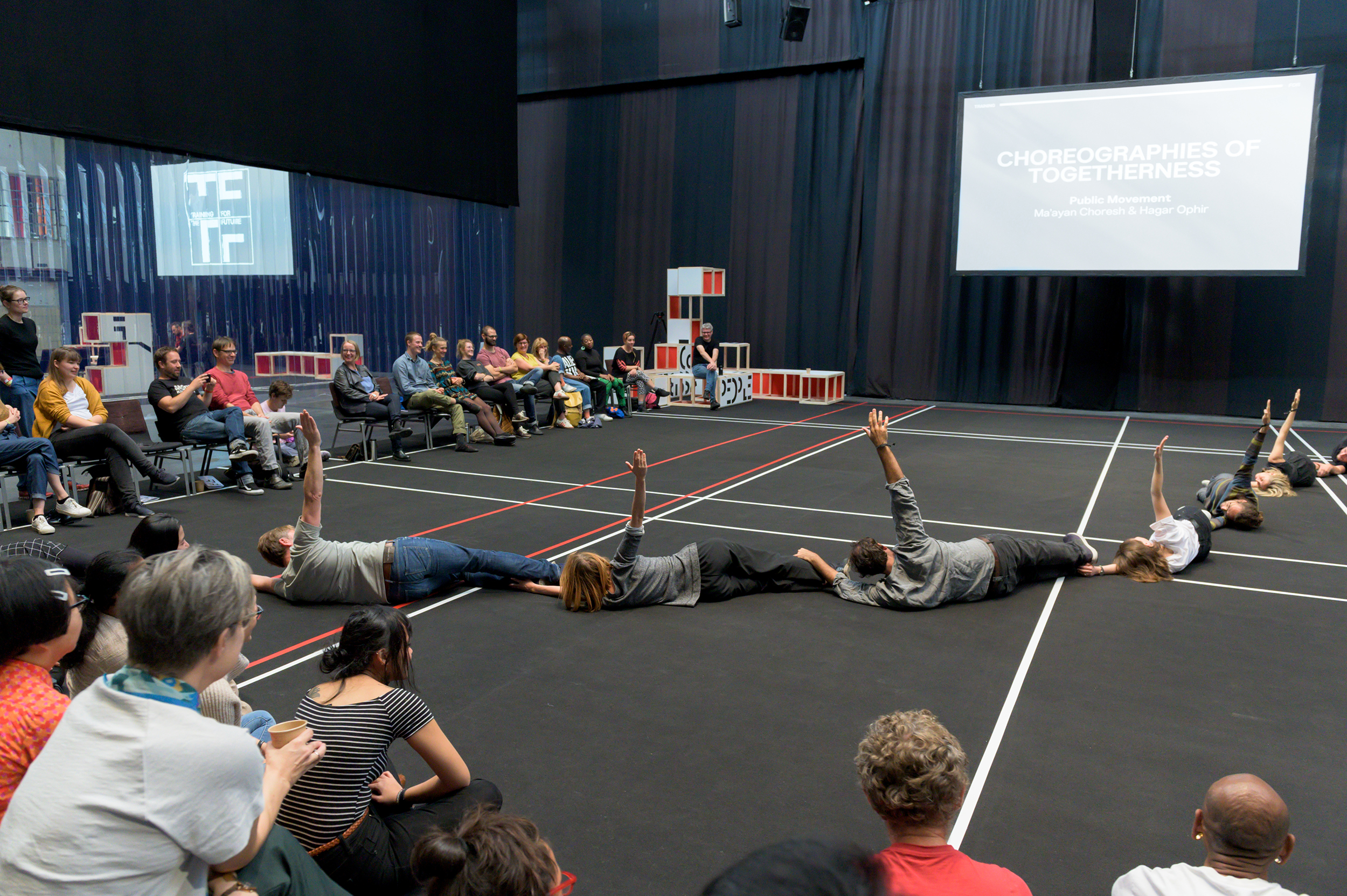

The mornings began with group movement exercises, “Choreographies of Togetherness,” organised by Public Movement (Ma’ayan Choresh and Hagar Ophir), who drew on police and military techniques. In one exercise we split into smaller groups of ten to fifteen participants. Some groups who were told they would be ‘the police’ were instructed to leave the hall. The remaining groups were then told to surround ‘the police’ and attempt to remove their members, one by one. Flipping the script, it was the police who then had to work out how to resist these incursions. For another exercise smaller groups formed into ‘human caterpillars’ with two heads that led the groups forwards and backwards across the grounds in front of the Jahrehunderthalle, emphasizing group and spatial dynamics in simple decision-making. For the final day’s exercise we were asked to think of an artwork that had been removed or destroyed and to somehow embody it, transforming it into a simple choreography that could be presented to the group. Such exercises that brought us together as collective bodies and identities, often pitched us against each other in physical confrontation or competition.

Multitudes

The afternoon blocks began with voicing, listening and movement exercises under the title “Multitudes of Listeners” led by Maya Felixbrodt, Germaine Sijstermans and Samuel Vriezen, who engaged us in modes of singing, articulation and vocal modulation. Working in pairs, and then together as a group, the musicians asked us to deconstruct our speech acts into circulating tones and resonances, voicing them together as a “plural voice, a collective ear, a shared resonance.” In the first session we engaged in a vocal drone as the basis of music and as a means of being with one’s thoughts, but still together as a group. We were encouraged to ask questions which Multitudes sang back at us and left hanging in the air as a song: How has the future changed? Is the past different? What should I do with my body? Answer some questions!

Trainings

Additionally, the three-day program was divided into six blocks of parallel training sessions. Each block accommodated around 150 participants, divided into two parallel sessions. In addition to the sessions I attended (as follows), there were also sessions with Institute for Human Obsolescence (Manual Beltrán) & Wael Eskandar; irational (Heath Bunting); ISD-Bund e.V. (Tahir Della) & glokal e.V. (Lucía Muriel); Klaas Kuitenbrouwer and Sjef van Gaalen; Not An Alternative (Steve Lyons and Jason Jones); and Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (Isabelle Frémeaux and John Jordan).

Friday: Block 1

Orgy with Machines

with The New Centre for Research & Practice (Mohammad Salemy and Nathalie Agostini)

The New Centre for Research & Practice is an international, non-profit, interdisciplinary higher education institute that fills a gap between undergraduate and graduate programs and institutions. Their session began with theorist Mohammed Salemy reading aloud a text concerned with the rise of the alt-right and their successful deployment of meme propaganda. To counter these strategies, Salemy urged like-minded progressives to enter into the ‘meme wars’, using examples from his Facebook feed. Before his lecture, Salemy distributed a short speculative fiction he had authored, sketching out a dystopian future in which a post-work society functioned under a regime of automated mass surveillance. Similarly, Salemy’s lecture also concerned an imminent dystopian future in which political discussion was reduced to meme-like viral media. Having declared ‘the trickster’ as an archetype that progressives should embrace, the workshop split into two groups to produce political fictions for social media. The ‘Twitter group’ were instructed to devise a future scenario from which they would Tweet as if it were the present. The ‘Instagram group,’ which I eventually joined, were given a set of images and asked to combine them with phrases so as to circulate them as memes.

As the group decided how to proceed, attempting to agree on an image, an issue, and the pros and cons of obscurity, I shot off a few fast attempts on Instagram before going for a snack. Picking over wheels of imported vintage Dutch cheddar (which were installed as ‘edible sculptures’ to get around the host organisation’s catering contracts), I chatted with early net/intervention artist Heath Bunting who was leading an upcoming session, “Intimacy of Encryption,” on coded language and counter-interrogation techniques. When I returned, I found my group divided. A handful of participants had set up an Instagram account and posted a short series of images that were critical of the exercise. Wrought with wry humour, they were no doubt influenced by the presence of Indonesian artist Natasha Tontey, who is of a generation for whom memes might be intuitive, spontaneous and less-laboured.

Meanwhile, the Twitter group imagined a future ‘neosovereign state’ of ThaiAotearoa, a fictional resistance movement fighting against the ‘Global North Coalition’ and their exploitative and genocidal ‘HalfEarthing’ strategies. Hinting at the North/South tensions that would come to mark our larger group discussions, the feed depicts germ warfare, nanotechnology and pictures Britney as an ageing celebrity supporter.

Klima Streik

Notably the Global Climate Strike (September 20, 2019) fell on the first day of Training for the Future and the first block adjourned early so the group could join the Fridays For Futures march as it advanced through central Bochum under a dazzling blue sky. As a coincidence in programming, the demonstration contextualised Training for the Future amongst local groups participating in a global day of action. For me it relieved some of the novelty, and dare I say cynicism, that often accompanies art–activism when it is presented in the institutionalized art world. It was also significant that a group of teenagers from a local drama program attended the following afternoon block, hinting at the intergenerational potential of Training for the Future.

Friday: Block 2

Redistributing Love

with Army of Love (Ingo Neirmann, Adriano Wilfert Jensen and Christian Bayerlein)

Led by Army of Love founder Ingo Neirmann and choreographer Adriano Wilfert Jensen, this session concerned communalizing love. As Neirmann explained, concepts of beauty are culturally determined; not everyone is equally attractive and thus does not have the same access to love. With relations between couples negotiated as ‘I love you as much as you love me’ we learn an exchange economy of love that is entirely privatized. As such, this session introduced skills useful for the redistribution of love as erotic justice.

Group identity was achieved with physical exercises that established intimacy through breathing, attentiveness and touch. Sprawled on the grass in front of Jahrhunderthalle and bathed in afternoon sunlight, trainees came together in pairs to examine each others’ hands, then in 3s with one given control over the hands of the other two. This progressed until the group became a morphing mass of caressing of bodies. Christian Bayerlein, a disability and sexuality activist and one of the session leaders with a notably differently-abled body, arrived late and was effortlessly absorbed into the group. There was no overt discussion of consent which was instead determined via ongoing tactile engagement. A passerby called out from an overarching gangway: So, this is Fridays for Futures? While his taunt made us suddenly self-aware, the group, engrossed in its task, carried on.

Saturday: Block 3

Killing the Dominant Male

with Center for Jîneology Studies (Ceren Akyos and Yasemin Adnan)

Akyos and Adnan are representatives of the Kurdish Women’s movement and the revolutionary struggle for Kurdish liberation of which the self-administered region of Rojava is exemplar. Given the specificity of the Kurdish women’s struggle, when transposed to a different context they aligned it with efforts to counter ‘toxic masculinity.’

The session’s title, “Killing the Dominant Male,” is a phrase attributed to Abdullah Öcalan, one of the founders of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and a leader of the revolution who was captured by Turkish Intelligence authorities in 1999. Held as the sole inmate of İmralı prison island on the Sea of Marmara, he has authored several books. “Killing the dominant male,” addresses male subjectivity alongside ‘dominance’ as an institutionalized practice and system. In a recent book Öcalan writes, “Class and sexual oppression develop together; masculinity has generated ruling gender, ruling class, and ruling state. When man is analysed in this context, it is clear that masculinity must be killed.”1

The Bangladeshi performer and journalist Akramul Momen offered that masculinity is also intellectual superiority (evident in the wage gap, the unequal distribution of care and reproductive labor) and that it is also evident in the art world. Indeed, Akyos and Adnan discuss how women also reinforce the dominant male as internalized patriarchy which they address with the revolution’s concept of ‘total separation’ or ‘divorce.’ We learned that Jîneology Studies, as a women’s science or cosmology, refers to the Kurdish word Jîn (woman) and its root Jîyan (life). In traditional Kurdish society women’s roles are as caregivers aligned with notions of nature, so the ongoing project of liberation is also a rebellion from these stereotypes. Women organize initiatives according to their needs and interests and thus divorce from five thousand years of male domination. The iconic Kurdish Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) is one example of such organizing.

Split into smaller groups of around five, Akyos and Adnan advised us to “Interrogate yourself!” as we discussed male and female role models. Then, using the modular furniture and props, we were instructed to collectively embody a living sculpture that somehow represents these discussions. Embodiment, they explained, is a means of generating empathy and is preferable to adopting roles and dynamics that reinforce domination or leadership.

“Rather than dominate,” suggested Mexican curator and writer Gaby Capede, “we can use our capacity to switch positions—our powers of fluidity—to embody empathy.”

Our group became absorbed in dialogue and gave little thought to devising a sculpture, so when the time came to present we simply improvised! All the male-identifying group members climbed into the box-like furniture, effectively making themselves invisible, prompting a discussion about how society prescribes roles and we attempt to fit into them.

“If you don’t kill your dominant male, we will have to kill you!” cautioned Akyos and Adnan, emphasizing the two revolutionary struggles ongoing in Northern Syria: a military struggle against Daesh and Turkish armed forces and a women’s struggle in society.

Saturday: Block 4

Extraterritorial Activism

with Women On Waves (Rebecca Gomperts and Victoria Satchwell)

This session began with a fast poll in which Rebecca Gomperts asked us to position ourselves in the space according to our responses to a list of rapid-fire questions: Should women have control over their bodies? Should women be able to have abortions without consulting the father of the foetus? Should women be able to have abortions after third trimester?

The exercise dramatized how the group intuitively thought about the governance of female bodies by spatializing opinions. Next Victoria Satchwell gave a brief overview on Women On Waves (WOW), a Dutch organisation founded in 1999 by Gomperts, a medical doctor, artist and activist. WOW provides abortions for women without access to safe reproductive services onboard a ship in international waters. Women on Web was founded in 2005 to provide online access to abortion pills.

Themed ‘hacking the system’, this session was devised around obtaining prescription drugs that could induce miscarriage. These are not abortion pills per se, but drugs based on the synthetic compound misoprostol, such as those used for managing arthritis.

After the group split into two, one group undertook a role-playing exercise about providing information to a friend or confidant who was seeking to terminate a pregnancy. I formed a group with two women accompanying a group of teenagers. They explained that some Muslim adolescents amongst them found the content challenging and were unsurprisingly shy about speaking up. Nevertheless these caretakers were pleased that their charges were being exposed to information that they may not be able to access elsewhere.

The second group effectively forged prescriptions under the guise of art, acting on ‘freedom of expression and information laws’. Gomperts stressed that the exercise was not about breaking the law, but rather demonstrated its availability for interpretation.

Sunday: Block 5

Transnational Campaigning

with School of Transnational Activism (Lorenzo Marsili) & European Alternatives (Martin Pairet)

Also beginning with a floor poll, participants were asked to position themselves in the room according to how strongly they agreed or disagreed on statements concerned with national and local organizing, the necessity of borders and the “class unity of the 1%.” The session was then poised to consider alternative forms of transnationalism.

Dividing into smaller groups, I joined Martin Pairet who led us through an exercise to identify six steps necessary to enter the European Green New Deal into the EU parliament. This focused and practical task sparked lively discussions: Are we organizing a social movement or a party? Who are the communities and groups that we think would form our supporter base? Young people and students would bring energy and enthusiasm while trade unions would have access to infrastructures and industries. What about migrants — should they be able to vote? How can everyone benefit?

We were asked to identify obstacles and potential enemies and also consider how to build on current energy and momentum, demonstrated by the Global Climate Strike we had attended on the first day. How might we tap the energy of these movements to build power and escalate our demands? Ultimately what would it take to usurp the interests of ‘old white men’ and increase the diversity of representation in the European Parliament? Whilst not being a citizen in the EU it was nevertheless a stimulating, speculative and provocative exercise in strategic political thinking.

Sunday: Block 6

Beyond Welcome – Agitprop for the Future

with Arrivati (La Toya Manly-Spain and Asuquo Udo) & Schwabinggrad Ballett (Liz Rech and Nikola Duric)

Liz Rech from Schwabinggrad Ballett, a neo-Brechtian performance, theatre and right-to-the-city activist group, began with a quote from philosopher Judith Butler: “For politics to take place a body must appear.” Her brief presentation introduced us to the group’s concerns, interventions and methodologies. For example, how they use costuming to claim and perform identities and also for protection. Group members also engage in over-identification to infiltrate nationalist rallies and confound them with absurdist demands and behaviour.

Following Rech’s introduction, we literally jumped into exercises to develop ‘movement choreography’ in which movement is deployed to break out of mental blocks and also forge intimacy and trust amongst participants. “When we move together we understand each other’s body language,” Rech offered as her and Duric took us through some of the steps featured in their documentation such as the “La Toya Dance” and “Silent Mirror.”

After a short break, we regrouped around La Toya Manly-Spain from the self-organized migrant activist collective Arrivati, who led us through a group singing ritual. We were asked to voice our ancestors, sing out our names without consonants, and participate in a song in honour of Oxum, a Yoruba orixa or spirit associated with waterfalls and the colour yellow who was invoked to ‘irrigate’ the gathering. Asuqua Udo then held forth a discussion on why he became an activist before teaching us the Asuqua step also often used in Arrivati’s and Schwabinggrad Ballett’s interventions.

This was followed by an experiment to use the floor plan of the Jahrehunderthalle as a music pad. Dancers were instructed to move to certain marked-off sections and thus trigger sounds voiced by a group of ‘beatboxers’ with loud hailers watching from the floor above. It was invariably noisy, haphazard and a lot of fun, demonstrating that activism can be exuberant and inclusive and that organization doesn’t necessarily mean militancy. Indeed, it can bring joy.

The last exercise was a swarming exercise in which different people took turns to lead the mob around the building, employing the steps we had learnt in the workshop alongside our own modifications and inventions. As a loose consensual mode of collective movement, swarming presented a significant contrast to the more regimented group forms that Choreographies of Togetherness drew from each morning—emphasising the tension between play and discipline that is arguably necessary for mass actions, occupations and other forms of creative civil disobedience.

Debrief: Training for Whose Future?

For me it was the evening sessions in which we came back together as a larger group to share experiences and get to know each other that were the most insightful. Here a group of artists/activists from South East Asia, the Pacific Islands and Latin America, who had been brought to Bochum by the Goethe Institute to attend “a crash course in art and activism”, made themselves known. As representatives of the so-called Global South, the Goethe Gruppe quickly established themselves as a critical bloc who challenged the assumed universality of concepts and the European bias of experiences being discussed. Effectively they questioned whose future(s) we were training for.

During the first evening’s plenum Alena Waqainabete, an activist working in Fiji, described how her community’s concept of the future extended only as far as the next fishing season. As the Pacific Islands lose their land mass to rising sea levels they carry the burden of lifestyles of the overdeveloped world, of which the Ruhr Triennale was an example. Furthermore, as they had all traveled some distance to attend, the Goethe Gruppe expressed frustration that issues of transnationalism were limited to Europe. Given hegemonic institutional whiteness in Europe, people of color often discuss how they are invited to participate in such programs to fulfil diversity agendas—and are thus interchangeable—rather than being valued for their unique perspectives, knowledge and skills. Indeed, the multidisciplinary Māori artist Jessicoco Hansell questioned the program’s pedagogical hierarchies and the divisions: What assumptions were being made about attendees? What issues were not being addressed? Who was missing?

“Where are the locals?” asked Singapore-based artist and provocateur Seelan Palay, before declaring that the next time he was offered such a trip he would rather the funds be used to ensure local participation – prompting others to ask why the technical staff and invigilators did not take part in the wrap-up assemblies.

“Where are your zines?” asked Nadira Ilana, a filmmaker and activist from Malaysian Borneo, noting the absence of a publishing culture associated with grassroots organising, significantly as a means to circumvent internet restrictions.

Commendably, Staal was responsive to these criticisms and participated in an extended debrief with the Goethe Gruppe before they departed. While Staal acknowledged his privileges as a white, male Western European, it is undoubtedly some achievement to establish such critical and ambitious ‘new institutions’ in contemporary art contexts that are often determined by commercial interests, cultural trends and nepotism. By bringing together artists working in social and political movements with activism as it appears in the art world, Training for the Future challenged the capacity of its organizers to accomodate a diversity of interests and expectations. Our futures it seems, if not yet cancelled, remain contested.

Footnotes

- Abdullah Öcalan. Liberating Life: Woman’s Revolution (International Initiative Edition and Mesopotamian Publishers, 2013): 51. http://www.ocalanbooks.com/#/book/liberating-life-womans-revolution

Sumugan Sivanesan is an anti-disciplinary artist, researcher and writer. Often working collaboratively his interests span migrant histories and minority politics, activist media, artist infrastructures and more-than-human rights.