Palácio das Belas Artes Lisboa: From Monument to Multimentality

Lia Carreira and Bernhard Garnicnig

November 2023

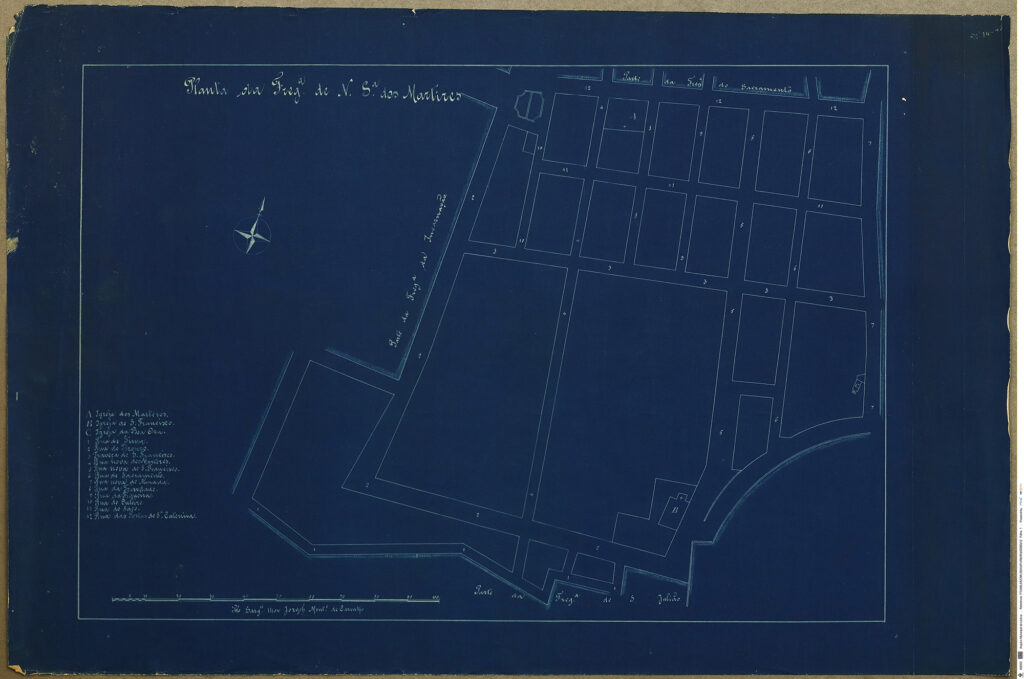

Map showing the location (“B”) of the Mártires Church destroyed in the 1755 earthquake, where the Palácio das Belas Artes now stands. © Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa | PT/AMLSB/CMLSBAH/PURB/003/00063/12

The contested space of cities necessitates the negotiation of the role of built structures in the formation of collective memory. The human tendency to forget – and, by consequence, to deny the humanity of others – is a “natural” process that we try to counter with memorialization. However, in public space, monumental scale becomes spatial hierarchy.

The contested meaning of built structures is directly linked to the role of property and architecture in competitive processes; for example, through negotiating between private wealth and the basic right to housing. As mnemonic devices, memorials compete for space in collective memory.

As Michael Rothberg argues, “dominant ways of thinking (such as competitive memory) have refused to acknowledge the multidirectional flows of influence and articulation that collective memory activates.”1 In other words, one history cannot be sealed off from other histories as they are transversally linked. Instead, memorial practices that continually reproduce the ambiguity of history and the multiple layers and folds of a site become a differential space that highlights the ongoing social construction of memory collectives.

To expand on Rothberg’s suggestion, multidirectional memory should not aspire to follow the same logic as real estate development – that is, that a site can only serve one memory. In contrast, multidirectional memorials have the potential to propose and produce the conditions for ongoing yet impermanent, multivocal yet agonistic memorial practices that create moments of presence.

Here, we present the Palácio das Belas Artes Lisboa in Portugal as a memorial to the promises and potential pitfalls of the concept of multidirectional memory. Following Palais des Beaux Arts Wien in Austria, this model is an attempt to avoid the potential problem of occupying space for a singular purpose even to arise. Without keys to Palácio das Belas Artes Lisboa, we are forced to continuously (re)invent ways to point to the past and its transversal connections while occupying the present. Yet, as we offload the cognitive labor of remembering to institutions, Palácio das Belas Artes Lisboa will still be in direct competition with the process of forgetting. If this fallibility of human memory and reciprocal humanity is the “natural” cause we try to resolve with memorials as institutions, how can these memorials be non-competitive? Or, perhaps they should not be considered memorials at all but rather a space for multiple mental models of considering what is “past” and what is “present” by addressing all registers of data and matter and pointing to all lines converging in that specific space.

Eduardo Alexandre Cunha, “Largo da Academia Nacional de Belas Artes, rua Victor Cordon e calçada de São Francisco,” 1940. © Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa | PT/AMLSB/ACU/002536

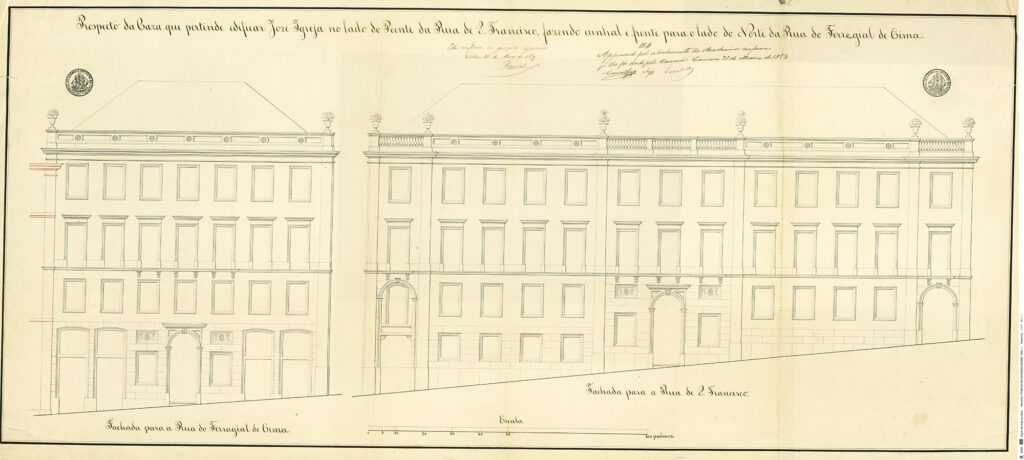

The Palácio das Belas Artes Lisboa is a memorial to the Iglésias family. Of Spanish origin, João Iglésias, together with his nephews, José and Manuel Iglésias, established himself in Lisbon in the late 1800s by building up a commercial enterprise in the city center. The region was of growing importance, becoming a sought-after site for a segment of Lisbon’s population on the rise financially and socially. From the financial autonomy that came with their prosperous business, the Iglésias family envisioned a manor representative of their aristocratic ambitions. Having inherited the ruins of a church construction site (destroyed by an earthquake in 1755 and bought at a government auction by their uncle), José and Manuel Iglésias commissioned a palacete to be built on the south side of a repurposed convent (Saint Francis of the City of Lisbon) in 1859. However, the construction of the building was fraught with spatial and financial disputes. Initially designed to preserve and incorporate the original facade of the crumbling church by giving it a new purpose, the original plan fell through when the municipality acquired part of the Iglésias’ property in an attempt to revitalize the area with the construction of a new public square for the already established Academia de Belas Artes (Fine Arts Academy) and the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (National Public Library). Ironically, it is this disputed square, Largo das Belas Artes, that gave the Iglésias’ manor its better-known title as the Palácio das Belas Artes. The building remained in the Iglésias family until 1936, when it was rented to the General Directorate for Livestock Farming and later sold in 1971 to the Portuguese State to house the Ministry of Economy.2

Architectural drawing of the Iglésias Palace as designed by Giuseppe Cinatti, 1859. © Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa | PT/AMLSB/CMLSBAH/GEGE/023/0553

The Palácio das Belas Artes Lisboa is a memorial to Giuseppe Cinatti (1808–1879), an Italian architect and scenographer active in Portugal from 1836, who was responsible for the design of the building. He is considered one of the most significant figures in Portuguese architecture of the 1800s, especially in the development of housing for a renewed liberal aristocracy. He was also known for his scenographic works, which he painted for the São Carlos, D. Maria II, Laranjeiras, and the São João national theaters. However, his great reputation as an architect was later questioned when the tower he designed for the famous Santa Maria de Belém monastery fell mid-construction in 1878. This event sparked criticism about issues ranging from labor conditions and the lack of construction regulations to the lack of competent practitioners and those responsible for safeguarding the national heritage. These criticisms could easily have been made today, as Portugal is home to a number of abandoned architectural masterpieces and, according to the National Statistics Institute (INE), ranks second among EU countries with the worst housing conditions.3 While efforts are made to preserve the facades of these buildings, the interiors are often left to crumble. Hiding behind the beautiful and colorful Portuguese tile-covered buildings from the late 1800s that still stand and provide housing for the general population, there are rotting wooden floors and staircases, leaky roofs, moldy walls, and an absence of necessary safety conditions. Although it has maintained its original exterior structure, Palácio das Belas Artes has undergone several reconstructions of its interior – not only to adjust to the needs of government offices but also to amend structural damage resulting from multiple earthquakes, a common issue the city has faced throughout its architectural history.4

left to right: Buildings of similar names in Vienna (Photo: Peter Haas), Mexico City (Photo: Carolina López), San Francisco (Photo: Rhododendrites), Lille (Photo: Velvet), and Brussels (Photo: Trougnouf aka Benoit Brummer).

The Palácio das Belas Artes Lisboa is a memorial to the Beaux-Arts brand of palácios, palais, and palazzi around the world. Its sister buildings can be found in Brussels, Vienna, San Francisco, Lille, and Mexico City/Āltepētl Mēxihco. The Beaux-Arts style, a form of neoclassicism that was en vogue from the 1880s to the 1930s, was the product of an era in which parts of society in central Europe experienced peace and prosperity, which led some to express their desire for archaic aesthetic structures by imitating antiquity and reappropriating it in architecture. Even though the name suggests a common typology of purpose for these buildings, they are surprisingly different. Some are the infrastructure for museums of municipal art collections, while others house businesses and apartments. The Palais des Beaux Arts in Lille, France, for example, is a purpose-built museum for the city’s art collection established in 1801 by decree of Napoleon’s minister, Jean-Antoine Chaptal. Chaptal, a chemist who had previously helped to speed up the production of gunpowder for the empire’s expansion and whose job as minister was to optimize government structures, initiated the transfer of works of art from the Paris Louvre, which was overflowing with the spoils of Napoleon’s wars, to fifteen cities throughout France. About a century later, construction began on the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City/Āltepētl Mēxihco, which was completed thirty years later. Originally planned as one of the public works to commemorate the centennial of independence from Spain, the building was constructed on the ruins of a former convent, which itself was built on the remains of indigenous structures. The building houses permanent murals commissioned for the site, an opera, and an architecture museum. As these two buildings are linked by their instrumentalization in the crafting of empire and state, this common thread connects them to the history of the public museum and its role in creating an imagined community with a shared history and comportment. As with other buildings of the same name in Brussels, Vienna, or Lisbon, they also share a projection of aesthetic values that represent the aspirations of the time outward through their facades.

The collective STOP Despejos during a protest in Lisbon against the wave of evictions that have taken place in recent years as part of the housing crisis. Courtesy of STOP Despejos

The Palácio das Belas Artes Lisboa is a memorial to the housing crisis in Lisbon. Through its recurrent transformations – from an ecclesiastical site to an aristocratic family home in the late 1800s, to then being converted into government offices in the 1930s and 1970s – and as it now sits, awaiting a luxurious fate, it is deeply intertwined with Lisbon’s turbulent social and economic past, which reverberates not only through matters of ownership, inheritance, and real estate investment but also through matters of migration, discrimination, and gender rights, all tinted by its colonial past. Since 2010, house prices in Lisbon have risen by 80 percent and rents by 28 percent.5 The city has about 150,000 empty houses, and the Palácio is one of them.6 It was bought in 2015 for an astonishing 18 million euros by the Pension Funds of the Bank of Portugal, which, through other recently acquired buildings in Lisbon’s historic center, has allegedly been profiting from luxury apartment rentals. Located in the heart of the city, within walking distance of key tourist spots and important government facilities, the building is of course of great economic value to both the public and private sectors. Yet it is a monumental affront to the struggling lisboeta (Lisbon residents) who barely make a living as tourism-inflated rents surpass their €740.83 per month minimum wage. Lisbon’s tourism-based economy has then taken the city hostage, with the Palácio’s Santa Maria Maior neighborhood having the highest number of short-term lodgings, amounting to 60.7 percent of the available housing in that district alone.7 This scenario of scarcity is aggravated by a growing and much-needed migrant workforce as the younger generation of Portuguese flees the country for better pay and its remaining citizens grow older. These migrants, mostly from Portugal’s ex-colonies and empowered by new welcoming regulations, arrive into a multilayered housing crisis while having to deal with impending rental bureaucracies and with the nation’s unresolved social and racial prejudices. In addition, discrimination has a strong gender element, with 82.7 percent of cases involving discriminatory actions toward migrant women.8 Left without better options, migrants find themselves in dangerous situations as they are exposed to health hazards from overpopulated lodgings and unfit building structures.

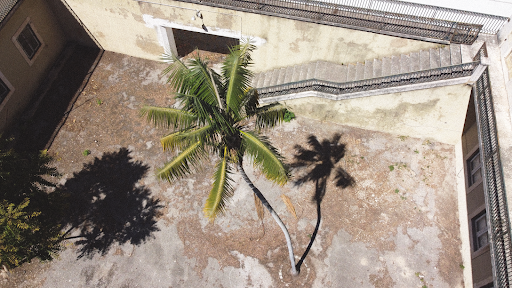

The last standing palm tree of the Iglésias manor – the subject of an ongoing digital exploration by Porto-based Brazilian artist Gaspar Cohen for the Palácio das Belas Artes Lisboa’s first exhibition. Photo: Carlos Campos

The Palácio das Belas Artes Lisboa is a memorial to the concept of the museum as an institution of memory that grounds its foundational legitimation in its physicality and in the preservation of material objects, in halting their decay and presenting them as having value in stasis. As suggested by the Portuguese legislation for the legitimation of local museums, according to the law n.º 47/2004, the recognition of an organization as a museum is still anchored in the requirement of the institution to maintain not only a physical space but also a collection of material objects.9 As decolonial studies of museums have revealed, these organizations implicitly become necrological institutions, making the prescription of this purpose grounded in violent histories of dispossession and expropriation. Therefore, this requirement must be abolished in favor of a concept of the museum as an institution that prioritizes the maintenance of practices and their material and immaterial instantiations, as a support infrastructure for the struggles of their collective context, in which the society they serve is understood as an ongoing association of individuals. Especially after the 2020 pandemic, in which museums felt the fragility of their physicality and material-centered practices, this shift has become imperative. The digital turn that began in the late 1990s with the popularization of the World Wide Web became more than an institutional digital strategy in a post-Covid-19 scenario: it became essential to their survival. However, beyond its status as an “extension” of the physical museum space, the online museum must also be valued as a “stand-alone” platform.

Sann Gusmão, photo documentation of housing crisis protests in Lisbon, Portugal, projected on the Palácio das Belas Artes building, April 2023. Photo: Lia Carreira

The Palácio das Belas Artes Lisboa is a memorial practice that experimentally engages with the past and present through forms of digital and public art. Because the site has undergone multiple reconstructions, one on top of the other and one after the other, the Palácio takes the form of a spatial palimpsest where the past is not fully overwritten but, in fact, superimposed to the point of permeating prescribed limits. Within this building, burial remains and forgotten religious artifacts have resurfaced through routine reconstructions of its neoclassical foundations, amalgamating temporal markers. Dissolving layers of wallpaper and paint reveal interior surfaces; longstanding balconies testifying to past purposes of domestic entertaining are later resignified as corridors of light and ventilation for government offices. These layers have no hierarchies, nor do they need to be set in contrast to each other. Rather, they are waiting to be immersed, pulled apart, shuffled, reused, multiplied, and expanded in practice. The digital seems to allow for an ongoing discontinuity of temporal and spatial coexistences as it occupies no concrete space. Its indefinite malleability allows for the reproduction, restructuring, and reimagining of its global physical siblings. Public art, on the other hand, allows us to materially connect the digital to the building’s surroundings while clashing the plasticity of the “outside” with the rigidity of the Palácio’s facade. Together, this becomes a renegotiation of histories and memory, from the private to the public, from the individual to the collective. The Palácio das Belas Artes Lisboa, as an online platform for art and exhibition-making, comes as a critical gesture in a country where colonial triumphs and dictatorial ideals are still praised here and there, and where, consequently, the competitiveness of recognized collective memories of violence or trauma is not yet fully on the table. Rather, the present discussion still lies in whether they are legitimate forms of contestation. Multidirectional memory, as a guiding concept, comes in, therefore, to reiterate the need for a debate of ongoing, non-competitive collective memory and identity.

Footnotes

- Michael Rothberg, Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), 18.

- For more information on the Palacete Iglésias, see SIPA – Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico, “Palacete Iglésias / Edifício no Largo da Academia Nacional de Belas Artes, n.º 2,”, July 27, 2011, link.

- INE – Instituto Nacional de Estatística, “Censos – O que nos dizem os Censos sobre a habitação,” 2021, link.

- For more information on Giuseppe Cinatti, see Joana Esteves da Cunha Leal, “Giuseppe Cinatti (1808–1879): Percurso e obra,” (master’s thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 1996), link.

- Eurostat, “Housing in Europe,” 2021, link

- INE – Instituto Nacional de Estatística, “Censos – O que nos dizem os Censos sobre a habitação.”

- INE – Instituto Nacional de Estatística, “Censos – O que nos dizem os Censos sobre a habitação.”

- Casa do Brasil de Lisboa, “Relatório: Experiências de Discriminação na Imigração em Portugal,” 2020, https://casadobrasildelisboa.pt/projeto-migramyths-desmistificando-a-imigracao-lanca-relatorio-experiencias-de-discriminacao-na-imigracao/.

- Diário da República, “Lei n.º 47/2004., de 19 de agosto,” August 19, 2004, link.

Lia Carreira is a Lisbon-based Brazilian curator and researcher with a focus on experimental curating and exhibition spaces, particularly in Media Arts. Her projects address the use of new technologies in and for the exhibition space and her research expands on the histories of exhibitions and their spatialities. She runs and curates the Palácio das Belas Artes Lisboa in Lisbon and is the co-founder of the independent research project AI, Architecture and Exhibitions (AAE). She is currently finishing her PhD in Art at the Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton (UK), on the relationship between exhibition spaces and experimental laboratories.

Bernhard Garnicnig works in art, education, and research. His recent work analyzes the effects of institutions and technologies and contributes to the development of experimental and sustainable practices. With Artist Project Group, he recently developed a curatorial framework, exhibition, and publication around the role of The Artist as Consultant. He is the institutional director at the Palais des Beaux Arts Wien, where he proposes formats for exhibition and commissioning. He teaches Institutional Theory at the Department of Expanded Museum Studies at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, Post-Digital Media Pedagogy at the Department for Art and Education at Kunstuniveristät Linz, and Media Theory at the Higher Federal Institution for Graphic Education and Research in Vienna.