Slippery When Wet: A Conversation with Tiffany Sia

Karen Cheung

May 2021

During the 2014 student-led protests known as the Umbrella Movement, artist, writer and filmmaker Tiffany Sia was closely following the political events unfolding in her home country Hong Kong while living in New York, an experience she has described as “jetlag.” Four years later, she moved back to Hong Kong and was involved in the 2019-2020 protests and, as an affect stenographer, oral historian, and subversive witness, produced a body of work that documented her experiences around these historical events. On occasion of her first institutional exhibition Slippery When Wet at Artists Space and publication Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕 (Speculative Place Press, 2021), Tiffany and I discussed her expansive artistic practice and her thoughts on the futurity of Hong Kong.

Tiffany Sia (b. 1988, Hong Kong) is an artist, filmmaker, and founder of the Speculative Place residency. She is the author of 咸濕 Salty Wet (Inpatient Press, 2019), a chapbook on distance, history, and desire in and outside of Hong Kong. 咸濕 Salty Wet is in Tai Kwun Contemporary’s Artists’ Book Library collection and Asia Art Archive as part of the collection of print materials made in response to the Anti-Extradition Bill protests. Sia is the director of the short experimental film Never Rest/Unrest (2020), which screened at MoMA Documentary Fortnight, Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival, and Prismatic Ground, co-presented by Maysles Documentary Center and Screen Slate. Sia is part of Home Cooking, an artist collective founded by Asad Raza, to which she contributes the performance and reading series “Hell Is a Timeline.”

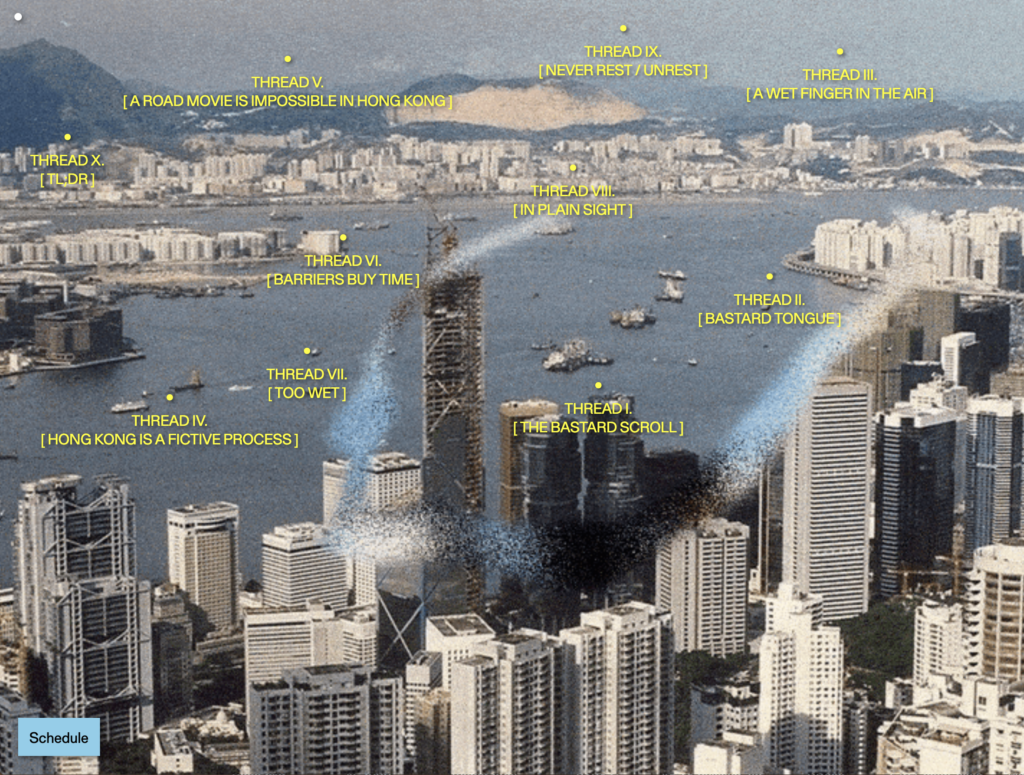

Tiffany Sia. Slippery When Wet (website view), Artists Space, 2021. Courtesy of Artists Space, New York.

Karen Cheung: I wanted to begin with the notion of distance that is threaded through the works on view in your exhibition, Slippery When Wet, which you described as “fraught channels to make the shortest distance between two places”: Artists Space in New York and Speculative Place, your artist residency program and project space on Lamma Island, Hong Kong. Can you speak about your desire to shorten the geographical distance between these two places for both yourself and your audience?

Tiffany Sia: To draw the shortest distance between two places is a poetic provocation to collapse geographical distance between narratives and to name the storyteller, whether it is in the form of text or moving image, as an agent who uncovers a wormhole to another place.

KC: In contrast, you have observed that one’s physical presence does not simply guarantee cultural proximity, and you have identified phenomena such as protest tourism in Hong Kong as a perverse form of spectatorship. Details of your experience on the ground in protests and the physical toll and trauma your body has taken on that you discuss in your book, Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕, make me wonder why you still referred to yourself as a witness to these events and why you’ve expressed a fear of contributing to the numbing consumption of violence through your writing.

TS: If committing lived experience to words can be described as a process of translation from embodied knowledge into written text, an author/poet/writer takes the role of reducing embodied experience into a series of events told from one perspective, no matter how exhaustive the work may be. It was critical for a text that enters a collection of records documenting this violent time to make known the ubiquity of violent images that make up the documentation of these events, and that, in the Susan Sontag sense, there is a danger of numbing people to “the pain of others” when describing a kind of “conflict narrative” from the frontlines, whether or not it is literal war.1 To put it crassly, in conflict narratives violence becomes a trope.

When you live through an event like that, it is not uncommon for many people to feel that no matter what position they took someone was more “at the front” than they were. It is the “daisy chain of the front” that connects us, which I write about in Too Salty Too Wet. Those at the mass demonstrations didn’t feel like they were present for the most unpredictable and violent confrontations with the police. Those of us who were teargassed may not have been the ones beaten up or violently arrested. Those who were arrested and tried in courts felt like they still had the privilege of visibility, unlike a young person who disappears into a black site with few or no witnesses. Perhaps it is an endemic fraudulence that you are not entitled to your own experiences and pain, and that describes a response of trauma.

Tiffany Sia. Slippery When Wet (website view), Artists Space, 2021. Courtesy of Artists Space, New York.

KC: The elusive feelings of guilt engendered by trauma are often interwoven into conversations about Asian-American identities. In your exhibition catalogue TL;DR you quoted Hamid Naficy’s proposition that a sense of belonging in a new place and connection with an old place can be constructed through the cultural vehicle of television and media for communities in exile.2 This reminds me of one of your exhibited works, A Wet Finger in the Air, a three channel installation playing archival television footage of local and international weather forecasts from the 1980s and 1990s. What is the significance of these weather reports?

Tiffany Sia, A Wet Finger in the Air, 2021. Courtesy Artists Space, New York. Photo: Filip Wolak

TS: Living is primary. The works, whatever form they take, serve to expand the boundaries of how we understand historical change and the material experience of living through this event. I’m interested in making clear the mediating forms and apparatuses through which we document time. A Wet Finger in the Air uses weather reports as a metaphor for locating these atmospheric changes. Each component by itself is incomplete, but together the works in Slippery When Wet are meant to be braided by the viewer into a broader picture. The exhibition weaves a narrative about the body as a recorder of trauma, the loss of knowledge through diaspora, and what it means for a place to reckon with irrevocable loss and change. What is the mood of this time? A Wet Finger in the Air, a set of newsreels playing in an ambient loop, is about the elusive dimensions of our quickly disappearing present.

KC: The weather reports were given in both English and Cantonese, but subtitles are omitted. You have also taken the same approach in your film Never Rest/Unrest and in your writing. For example, you refuse to translate the Cantonese phrase 無聊到死 in Too Salty Too Wet. Can you explain the absence of translation as a choice in your work?

TS: The absence of translation and its ethos is foretold in the blank glossary that begins the text. It demands that the viewer or reader be comfortable with swimming in a place of unknowing. Moreover, translation, in some ways, reduces language to a prescribed meaning. I refuse to comfort readers who, in Édouard Glissant’s words, are from “elsewhere,” readers who “don’t deal very well with unknown words or who want to understand everything.”3 It is to take up the mantle of Glissant’s notion of opacity as a practice of generative refusal, in faith with his notion that “to feel in solidarity with him or to build with him,” the poet, the artist, the author, “or like what he does, it is not necessary for me to grasp him. It is not necessary to become the other (to become other) nor to ‘make’ him in my image.”4 One can do the work of cultural translation, but translation doesn’t guarantee understanding, and certainly doesn’t guarantee empathy. I interpret Glissant’s “right to opacity” as a defiant refusal to assume the obsequious position of an informant.

KC: This defiance also takes shape in the redaction and withholding of information from your readers. For example, you redact protest chants, and you cite two pivotal dates, August 31, 2019, and June 30, 2020, but instead of naming the events that happened in Hong Kong on those dates, you asked your readers to learn about them. How do these gestures shift agency or even change the relationship between you and your readers?

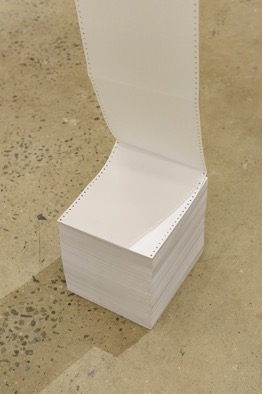

Tiffany Sia, Bastard Tongue (detail view), 2021. Courtesy Artists Space, New York. Photo: Filip Wolak

TS: The use of redaction has a very real and practical function under prevailing laws. Because I am already weaving and radically reframing history, I’m ambivalent about artists taking the voice of news reportage and having to literally explain current events and those of the recent past. That work is more effectively done by journalists. For me, the impact of an artist lies less in their ability to rehash the news and more in their ability to describe the mood or feeling of these times, which the news cannot do. Again, this goes back to the idea of the blank glossary. In describing events from faraway for international readers, I demand that the reader take an active role in learning about another place. Cross-cultural literacy needs to be taught, but it cannot be learned passively.

KC: When you translate certain words for your readers, there is an intentionality present, almost adhering to a formula, in this mode of translation: traditional Chinese, phonetic spelling, literal translation or denotation, then contextual meaning. Can you speak to this intentionality?

TS: In translating, I believe it’s important to convey the context and tone of Cantonese and how multivalence is built into the playfulness of the language. As a colloquial language, it is critical to hear the words. I wanted to specify to the reader how I read these characters in my head when I see them and to teach the reader how each word is sounded in Cantonese. Employing these varied modes of translating not only allows the reader to get closer to the meaning of these words, but also maps what this language does. I don’t think that’s necessarily a formulaic employment of translation, but rather the best way I know how to shuttle meaning between two languages is to do so in varied and simultaneous strategies. In a sense, a brief story is deployed for every word. The denotation and contextual meaning emerges between literal and figurative translation. The literal translation of these words would make poetic gestures to paint scenes and images, whereas the figurative and central translation describes the meaning the words convey in an American English vernacular. What exists between the literal and figurative is a fertile site where we can reframe our understanding of certain concepts, generally recognizable or culturally specific.

KC: Your written accounts of the Hong Kong protests are in English, while your father told his family history in Cantonese and wrote it in English. In the epilogue of Too Salty Too Wet, you ask: Is my account legitimate if it is written in English? Why did you choose to write this book in English?

TS: If being bilingual is like being ambidextrous, English is the hand that I write with. While I’m fluent in Cantonese, I only can partially read and write in Chinese. Also, I am much more adept at untangling and being specific about my feelings in English. To use English also has a specifically tactical function of being able to communicate across former commonwealth diasporas. The text, Too Salty Too Wet, is explicit about the political imperative to make connections across post- and neo-colonial histories. I have an ambivalent love for the English language and, as Hong Kong cultural theorist Rey Chow describes, to write in English “enables me to speak and write by wielding the tools of my enemies.”5 But it is also to be able to make connections across authors of dispersed colonial histories, as the work weaves in texts (some translated from other languages) by Édouard Glissant, Edward Said, Rey Chow, Ackbar Abbas, Lisa Lowe, Achille Mbembe and more – all texts that I read in English. So, to write in English allows for me to speak across diasporas and across anti-police and anti-authoritarian movements, and that is really critical for my work.

In asking the question Is my account legitimate if it is written in English?, I am being facetious in some ways. As I explain in the text, I’m not interested in claiming a role of the legitimate speaker of a culture, and, actually, I think that to capitulate to the logic that demands a certain idea of cultural authenticity, a cultural oneness (as it relates to Hong Kong), is to ignore the complex and paradoxical nature of Hong Kong’s history and culture. At worst, it gives into dangerous nativist logic that alienates a lot of authors from a more capacious discourse on the slippery nature of post- and neo-colonial identity when speaking about Hong Kong, a place that is host to a two-vector diaspora. And to be clear, my father, born in Shanghai, told stories in both languages. In English the stories are told more formally in written form and in Cantonese he told them aloud often with a certain ease, but also looseness of detail that was sometimes more descriptive. At times, the stories he told in Cantonese cast doubt on the stories he told in English. Details and some facts were volatile and opaque, and that’s the nature of memory and passing stories from one generation to the next.

KC: Speaking of accounts of history, you ended Never Rest/Unrest with archival footage of Hong Kong’s Handover Ceremony in 1997. Can you share your editorial decision to bring that watershed moment in the city’s historic timeline into dialogue with the Hong Kong protests that began in 2019?

TS: The last sequence is talked about so little in many interviews I do, but it is so critical to thinking that is central to what constitutes (and, therefore, how to film) historical change. The 1997 handover was a political pageant, a military display. On television, the political actors sitting between flags enacted a symbolic shift of sovereignty. Of course, the handover happened within the history of the British monarchy and its evolving relationship to television, between royal weddings and coronations over the last century. But for China, the handover simultaneously marks the country entering the realm of global television, another milestone being the 2008 Beijing Olympics opening ceremony. But what is so interesting about this televised handover ceremony, and this particular sequence showing the handover of sovereignty, is that it bears little emotional weight for people in Hong Kong. After huge anticipation, the collective memory that left the greatest impression (from speaking with many people over the years) is this one unifying detail: it rained a lot that day. Mirroring the ephemerality and elusiveness to describe these times, Hong Kong’s wetness is lived, and the ontological aspect of wetness is an illuminating metaphor for how slippery and difficult it can be to grasp moments of change.

Never Rest/Unrest captures a series of moments, externally banal, that attempt to get at historical change embedded in everyday lives, illuminating the personal narrative so much more than flaming barricades can. So, in contrast, I chose to end this film with the highly choreographed political ritual showing the banality of these two colonial structures shifting sovereignty and whose underlying principle is violence. The juxtaposition between the aspect ratios of most of the film and this last sequence asks: What kinds of spectatorship do we engage with when looking at moments of historical change? Or rather, what kinds of spectatorship are we invited to and expect to see? Tropes of documentary filmmaking prevent the viewer from seeing certain types of narrative devices, like using violent footage to tell the texture of historical change, but that is simply one aspect. It is also about trying to tell that psychic and affective space that rules these cusps is the work of poets. Working between text and moving images, Too Salty Too Wet and Never Rest/Unrest try to dismantle these ideas and examine how we receive information in troubling times.

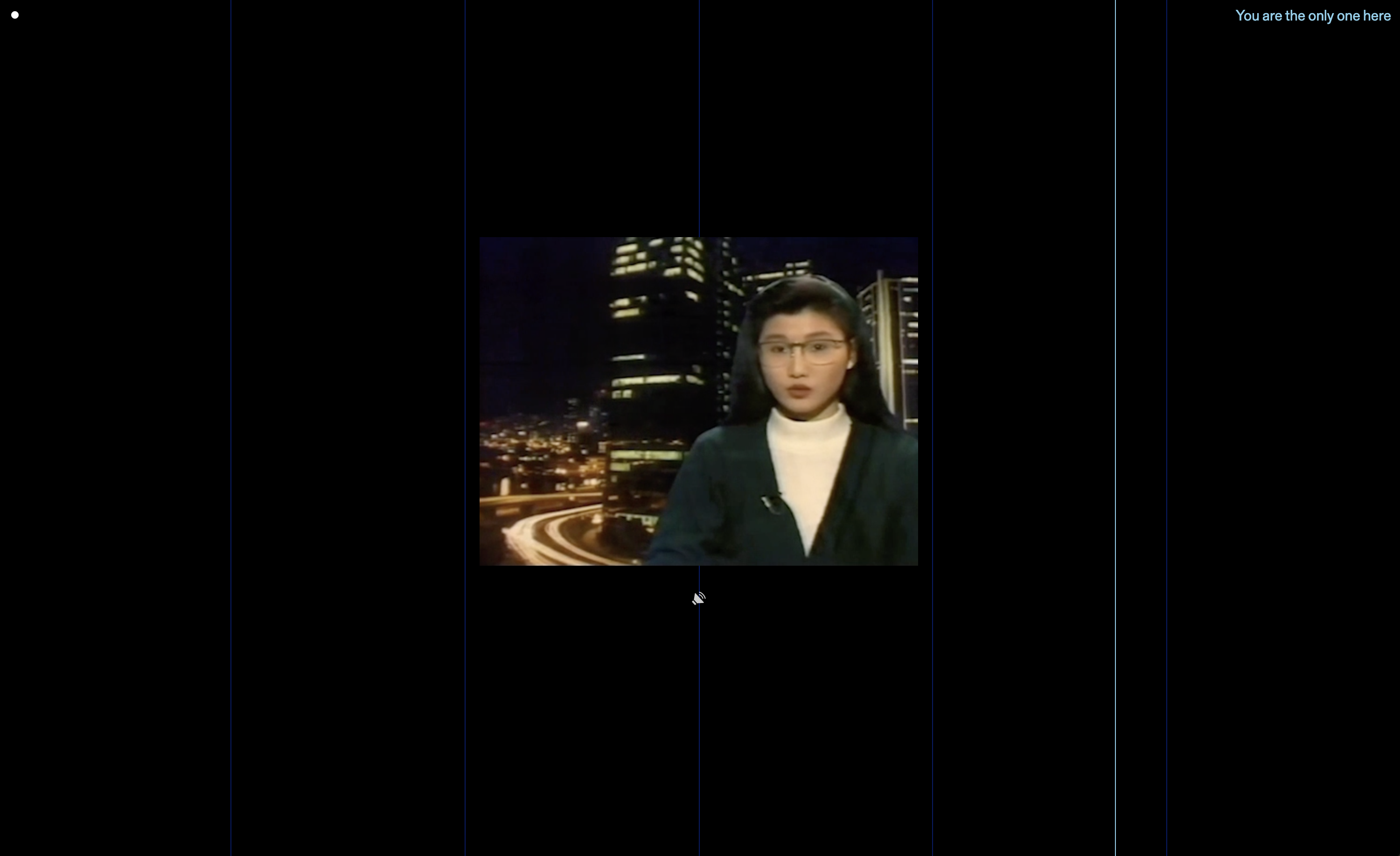

Never Rest/Unrest, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

KC: I think it’s only through your film that I’ve watched this ceremony, and it was funny to see all those representatives from the UK just watching, almost like a tennis match.

TS: That’s very on point because it describes the kind of spectatorship I’m talking about. I’m also thinking about the kinds of spectatorship we engage in, or are invited to, when we view historical change. People are interested in how these events impact people, but I think there are all these tropes of documentary filmmaking that prevent us from seeing past certain ways of telling a story about historical change. I’m very frustrated by that, both as a writer and as a filmmaker. While working on Never Rest/Unrest and Too Salty Too Wet, I was trying to dismantle or challenge those ideas because I think reading history didn’t prepare me for living it, you know? And we all probably feel that way about a particular crisis that we all share globally right now. How do I make sense of everyday time, the time of history and news time? We’re all constantly switching between altitudes of time. Moving through time and experiencing events like the Hong Kong protests, whether you are in or outside the city, can feel chaotic. Members of the Hong Kong diaspora, especially, who are living in the time zone of the news of another place, experience even more chaos.

KC: You have also written in Too Salty Too Wet how we’ve relied on the news media to give language to the Hong Kong protests. With geographic distance, I can only follow what’s happening through certain news media outlets. My dependency on those secondary accounts contributes to the chaos that you’re referring to.

TS: I think that’s really critical, especially in thinking about history as a series of receipts, as a historical practice of looking at primary and secondary accounts. Too Salty Too Wet is a type of primary account. I feel there’s this overwhelming dominance of secondary accounts and it’s really critical to move away from that. Looking at the primary accounts is also kind of a metaphor for thinking about the front lines. We don’t think we’re at the front, but we’re actually at the front just by living it. Whatever conditions our lives are, and wherever we are in this event, if we’re part of the Hong Kong community we are living it in our lives and writing that actively.

KC: In thinking of actively writing about our lives, if you could possess a metaphysical power that allows you to manifest an alternate future for Hong Kongers, or to will Hong Kong’s path in a different direction, what would that future look like as a weather forecast?

TS: I don’t think it’s ethical to be prescriptive about what alternate future I want for Hong Kong, and I don’t believe one person should claim the authority to imagine that, or impose such an imagined narrative on others, especially for a place with such a complex history. In Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕, I write that Hong Kong is a fictive process. In saying that, I believe we all have a role in writing these terms in incremental ways, whether or not these directions can be clearly articulated. These terms are written by how we live our lives. When Glissant writes that every diaspora is a journey from unity to multiplicity, I believe in the power of that multiplicity to take shape in dispersed places and with varied meaning. Diasporic identity presents riddles. There is not one forecast that will describe the path that we’ll take.

KC: Yes, that premises your description of Hong Kong as a “dispersed project.” In asking your perspective on this impossible hypothetical, I was thinking that the ability to write ourselves into the future, albeit an imaginary version, can be an act of grievance and perhaps survival. Which brings us to your thoughts on mourning and naming the death of Hong Kong, whether that is a loss now or yet to come. You have made a plea for more witnesses, for more bastard accounts of these events to serve as receipts of history, especially when visibility is fleeting.

TS: What Too Salty Too Wet invites is: this is a primary agent, this is a bastard account, and it doesn’t matter if you are a person of the Hong Kong community in or outside this city. It’s a provocation to offer primary accounts into the archive and to really question the idea of legitimacy. Who are legitimate speakers in the place? And it’s to say that the idea of a cultural center doesn’t exist. Maybe you can describe that as someone who literally has their feet planted on the ground here, but I think it’s much more complex than that, and I think it has to be much more complex than that if we are to hold space for what is to come for Hong Kong in the next five, ten, fifteen, twenty years. What happens to the children of exiles?

There needs to be a broader space and language to think about identity and its relationship to physical land when the community itself is not necessarily just tied to physical land and has been part of shaping so many different Chinatowns around the world. So, I think it’s critical as a dispersed community to attempt to work in different ways and shape that discourse, which right now is being dominated by news outlet reportage and documentarians that offer a very particular secondary account.

KC: Returning to our discussion on futurity, I also want to bring up the French-Algerian artist Kader Attia’s idea of Repair that is inherent to keeping injuries visible, in a way to revisit sites of trauma to enable the healing process.6 This reminds me of your descriptions of re-experiencing trauma from the protests in your dreams. What are your thoughts on Attia’s notion of Repair?

TS: The conditions of thinking about futurity are so backwards for us because of the countdown timeline that we live in. Our historical milestones, between 1997 and 2047, are historical timelines lived in reverse, and I almost feel as if Hong Kongers are destined to live in this upside-down time that forecloses our ability to be authors of a radical futurism.

The idea of Repair is then more interesting because when we visit sites of trauma that is an act of going back, whether they exist in this sort of timeline of the 2019 protests or a much longer timeline over centuries – thinking about the legacies of bodily trauma, human trafficking, the coolie trade and sexual exploitation of Asian sex workers common to port cities hosting foreign military personnel and merchants – the violence and coercion that happened from this territory describe the history of penal colonies like it. It is important for us to recover our sense of self through understanding this much longer history that we are part of. We are part of a continuum of histories of penal colonies that illuminates our struggles not as an anomaly, but as part of a whole continuum of struggles and exploitation in the history of global capitalism that formed from colonial mercantilism. That necessitates us to be in solidarity with other struggles. That’s how I see my own life, work and political investment.

There is a common language or resonance between myself and my collaborators and friends who are also descendants of colonized peoples. I see that so clearly with my collaborators like Trinidadian-American photographer Sasha Phyars-Burgess. Trinidad is part of the Commonwealth and I see these relations in our friendship acted out through both material connections between us and how we envision what solidarity means. That comes from a very intuitive language of having certain shared politics, but also having these politics enacted through a deep care for each other. I think that is also part of repair. It’s the repair of friendship across these experiences. Even without full understanding – you may not know the extents of each other’s histories and place – there is still this inherent trust and an ability to see these historical connections.

In the words of K. Wayne Yang and Eve Tuck, “Decolonization is not a metaphor.”7 It is lived, either directly, or through the trauma narratives inherited from our ancestors and relatives. The way this comes into view through history reveals the inherent paradox and the complex systems of colonialism and its violence, as opposed to how colonialism and anti-colonial politics in popular discourse is increasingly invoked as a pedantic abstraction. I think there are deeply uncomfortable feelings around what it means to be truly reckoning with a colonizer where Hong Kong wouldn’t be the place that it is without the British colonizing this territory, and many of us wouldn’t have been born without this series of historical events that shaped this territory and brought people together. Or, what it means to be reckoning with a secondary colonizer and the seductive notion of returning to a “homeland.” It really comes down to my interest in trying to place Hong Kong within Glissant’s project by thinking about the Pearl River Delta as part of a sea of unity in the Poetics of Relation, and the radical potential of learning history as a critical mode of repair.

Footnotes

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (London: Penguin, 2003).

- Hamid Nafic, The Making of Exile Cultures: Iranian Television in Los Angeles (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993).

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), xxi.

- Ibid, 193.

- Rey Chow, Writing Diaspora: Tactics of Intervention in Contemporary Cultural Studies (Arts and Politics of the Everyday) (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), 22.

- Gabriele Sassone, “Injury and Repair: Kader Attia,” Mousse Magazine, May 10, 2018. https://tinyurl.com/33v4hfru. Also see: Kader Attia, The Museum Of Emotion (London: Hayward Gallery Publishing, 2019). https://tinyurl.com/jt337sxt.

- K. Wayne Yang and Eve Tuck, “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” in Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1.1 (2012): 1-40. https://tinyurl.com/3pvhk65c.

Karen Cheung is a writer and researcher based in Oakland, California. Her current research explores the ephemerality and affect of performance art in the context of audience participation. She has held various positions at the Vancouver Art Gallery, De Young Museum, and Asian Art Museum. She currently works in the curatorial department of Media Arts at SFMOMA.