Storying the Silence: The Archive of the Vereinigung bildender Künstler*innen Österreichs (VBKÖ)

Georgia Holz and Stephanie Misa

February 2024

Silences have frequencies. I want us to ask: How can we learn to hear silences that echo loudly, softly, or in code?

— Panashe Chigumadzi, “Hearing the Silence”1

As artists and curators working within the cultural landscape of Vienna, Austria, what we embark upon together is a process strengthened by shared interests, endless curiosity, and a determination to somehow carve a footnote into this colossal monument that is Austrian Art History. As members of an oft-forgotten Vereinigung bildender Künstler*innen Österreichs (Austrian Association of Wom*n Artists, VBKÖ), we are convinced of the radical possibility of the story that VBKÖ tells now and in the future. We are invested in its legacy and in its continuity as an important association that pushes forward a collaborative, intersectional, and queer-feminist spirit. At the same time, VBKÖ is also a physical space, one that continually hosts exhibitions and has a century-old archive within its holdings. In this essay, we would like to speak about the VBKÖ’s controversial history and how its archive has become a site for speculative methods that explore convergent and divergent – and at times haunting – histories within the association.

Façade of Kärntnerhof in Vienna’s first district and the site of VBKÖ’s attic premises since 1912. Courtesy of VBKÖ. Photo: Daniel Hill

Our current research project, “Anonymity and Absence: Archival Sites of Speculation,”2 asks: How does one confront archival blind spots and make productive sense of absences within an archive? If the current mode of systematization in archival science instigates epistemic violence, how can one confront the anonymous authorship (and witnessing) of the archive and give what is missing or silent legibility? How can the missing parts of an archive be embodied? And how can alternative and unwritten histories be woven into what is present within the collection? Through this work, we are determined to create an experimental space that seeks to understand what an archive is and what it could be, and to make sense of the documents we keep on the VBKÖ shelves, as well as those that are blatantly missing.

Front door of the VBKÖ premises. Courtesy of VBKÖ. Photo: Daniel Hill

The VBKÖ was founded in 1910 under the Austro-Hungarian Empire with direct links to aristocratic and bourgeois society. Since its inception, it has promoted female artists and advocated for the improvement of artistic, economic, and educational conditions of women at a time when Viennese institutions, such as the Secession, the Künstlerhaus, and the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, were exclusively male in membership and enrollment. Among the first notable achievements of the Association was a successful lobby for the inclusion of female students to the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna in 1920 and the establishment of a state prize for women artists in 1927.3

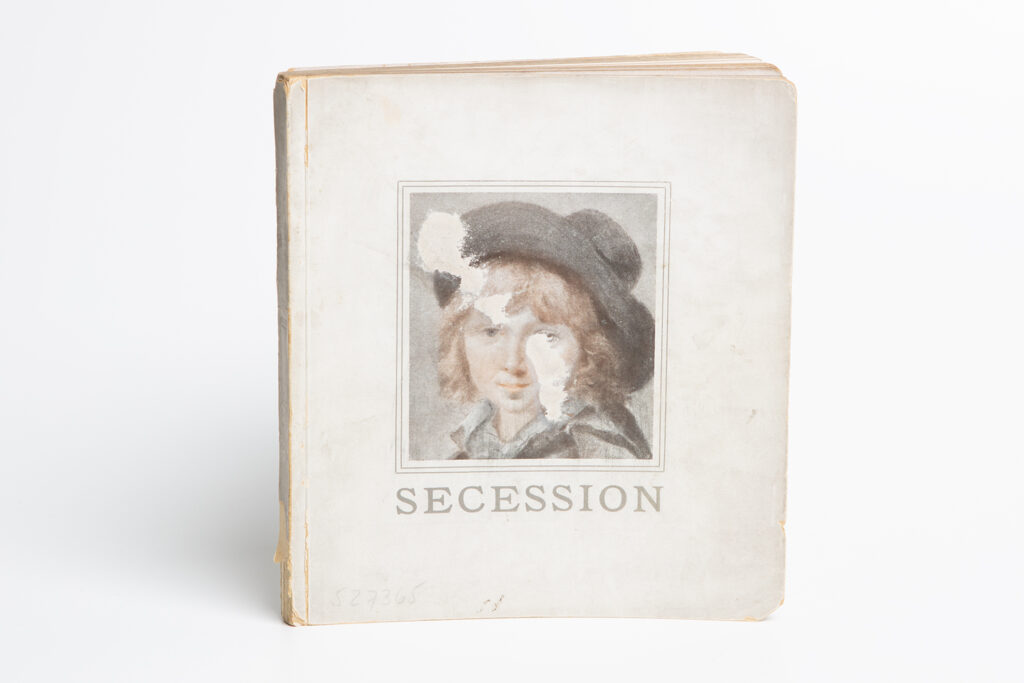

The association’s accomplishments in its early years, such as its landmark all-female exhibition “Die Kunst der Frau” (1910) at the Secession and the first attempt to write an art history dedicated to women, are well-documented and researched by art historian Julie M. Johnson in her book The Memory Factory: The Forgotten Women Artists of Vienna 1900 (2012).4 Although it was highly influential at the beginning of the last century as one of the four major artists associations in Austria, the VBKÖ’s achievements were quickly forgotten, and history would soon witness the VBKÖ contradicting and complicating its mission of feminist agency. As Johnson reflects, “although the ruptures of 1938 contributed to the invisibility of the forgotten women’s art unions [in Vienna at the beginning of the 20th century], it was the postwar focus on the ‘heroic years’ of the Secession that had the biggest effect.”5 Johnson adds that the role and involvement of women artists in the early history of the Secession has also been greatly overlooked due to the fact that the Secession’s membership would not include female artists until 1949. This overarching narrative continues to this day, and the shared history of the women’s association with the male-only associations has been greatly overlooked and remains unacknowledged by academic research in Austria.

Die Kunst der Frau: 1. Ausstellung der Vereinigung Bildender Künstlerinnen Österreichs, catalog published by the VBKÖ on the occasion of its first exhibition at the Secession, November to December 1910, 166 pages with illustrations. Courtesy of VBKÖ. Photo: Mark Chehodaiev

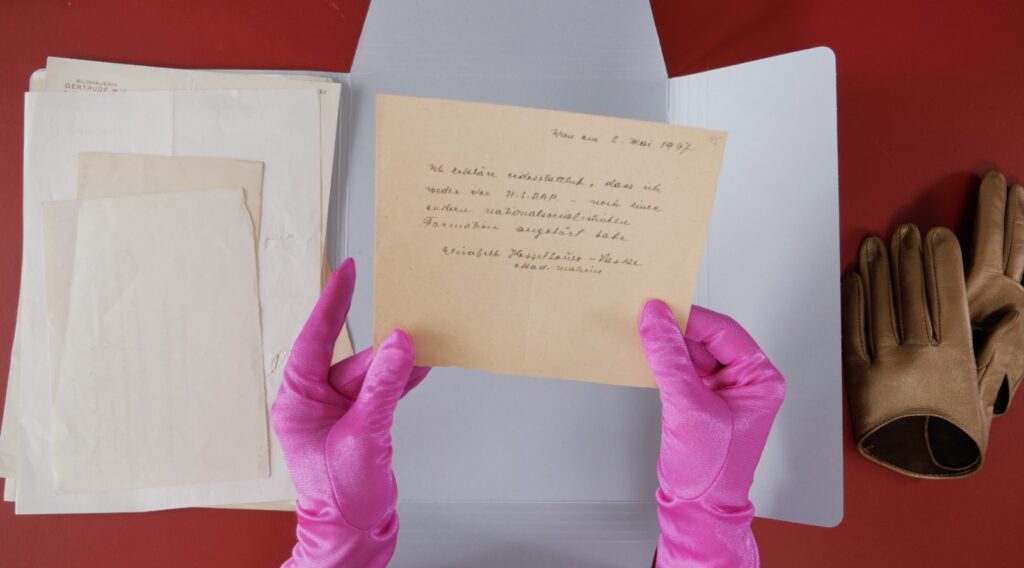

An interesting and almost forgotten resource that can contribute to changing this paradigmatic stance on early 20th-century female artists is housed in the VBKÖ archive. The collection is a typical association archive composed of secretarial files, documents of chairpersons and the association’s activities, as well as materials and works of its members. What is extraordinary, though, is that the archive has documented and survived the Gleichschaltung, a mandatory alignment with the National Socialist regime, with vestiges of the documents attesting to the ousting of all Jewish members, including VBKÖ’s president Louise Fraenkel-Hahn, and the installation of the infamous artist and committed National Socialist Stephanie Hollenstein as the Association’s president. Some preserved documents attest to the turmoil the association experienced in the aftermath of the war, and archival material from the years before, during, and after the war are glaringly absent.

The only existing group photo of VBKÖ members in the archive, original print, photographer: J. Marek, Vienna, presumably 1930, on the occasion of VBKÖ’s twentieth anniversary exhibition “Zwei Jahrhunderte Kunst der Frau in Österreich: Jubiläumsausstellung der Vereinigung Bildender Künstlerinnen Österreichs,” May 26 to June 9, 1930, Hagenbund, Vienna. Only six of the twenty members in the picture have been identified. 1st row, 2nd from left: Louise Fraenkel-Hahn (3rd president of VBKÖ); 2nd from right: Baroness Olga Brand-Krieghammer (1st president); 2nd row, 3rd from right: Helene Krauss (2nd president); further identified are Marietta Peyfuss, Johanna Kampmann-Freund, and Edith von Knaffl-Granström. Courtesy of VBKÖ. Photo: Mark Chehodaiev

While the archive is currently 113 years old, the association’s history is just at the beginning of its own documentation. As it stands, the VBKÖ archive remains undigitized and is only generally organized into three sections: Archive (ARCH), Publications (DRUCK), and artworks (WERK), categorized and documented in an analog Findbuch (reference catalog). “Archive” refers to original documents (handwritten or typewritten), including association registers, letters, and meeting notes, while “Publications” refers to all catalogs and printed matter ever published by the association. The most obvious absences are missing documents from before, during, and after National Socialism, but documentation from 1985 to the early 2000s is also very scarce.6 Some of the members’ works that were donated or inherited by the association were sold for the purpose of sustaining the association, especially in the 1980s.

The VBKÖ archive is administered and run by volunteers. The authors of this article are active members of its Archival Group, which is currently applying for funding to launch a project that will pursue a collaborative, interdisciplinary, and artistic reappraisal of the archive by developing both a display for the physical space of the archive at the VBKÖ and a digital platform for further artistic and scholarly practices. It is intended to be an active and dynamic place for (artistic) exchange and research that enables an active approach to (its own) history and documentation. Through its collaborative ways of working, the VBKÖ is clearly able to negotiate its own permeability with regard to its archive, and as an association that currently has a diverse group of members with different backgrounds, it wants to develop alternative formats that speak to this diversity and for this archive to reflect this change. It is, after all, an active association, so the question consequently becomes: How would we, as members, like to archive ourselves? How can the VBKÖ, as an institution, allow relationships to emerge within a collective “art history,” while at the same time fostering research with diversifying and decolonial perspectives?

VBKÖ, Who brings the cake?, video, 40 min, 2022. Courtesy of VBKÖ

In recent years, the VBKÖ archive has been an acknowledged resource for artists, curators, and art historians, and has made important loans to Viennese exhibitions at the Jewish Museum (2017), Belvedere (2015, 2019), as well as curating a discourse and performance program for the “Collaborations” (2022) exhibition at MUMOK (Museum of Modern Art Vienna). For “Collaborations,” members of the association collectively produced the video work Who brings the cake?, activating documents and stories held in their archive: stories of perseverance, of voluntary work, of communal efforts to keep alive a feminist spirit that has faltered and wavered throughout the years. This video work was also transformed into a live performative exploration, a durational piece in which members read aloud documents from the archive, letters, notes, and even emails, as well as a membership addendum (drafted to complement the association’s statutes in 2018) that tacitly expresses how VBKÖ members can “care for each other.” Another event from the program, titled “Critical Closeness: A Conversation on Archival Work,” was a film screening and panel discussion that explicitly looked at artists’ works that deal with archival research.7

Photo of a durational performance in the exhibition “Collaborations,” MUMOK, September 23, 2022. Participating members were: Hilde Fuchs, Fanni Futterknecht, Lisa Großkopf, Èv van Hettmer, Lena Rosa Händle, Daniel Hill, Georgia Holz, Neda Hosseinyar, Vinko Nino Jaeger, Cornelia König, Mary Maggic, Mika Maruyama, Stephanie Misa, Hyeji Nam, Aki Namba, Miwa Negoro, Berenice Pahl, Denise Palmieri, Selina Shirin Stritzel, Käthe Schönle, Barbara Stöhr, Johanna Tinzl, Julia Wieger, and Hui Ye. Courtesy of VBKÖ. Photo: Marisel Bongola

Despite significant academic research, especially by American scholars, the history of the VBKÖ and its achievements are largely unknown and have not been inscribed in the public collective memory in Austria. The desire to counteract this and to initiate broader memory-making with regards to the association is closely linked to the demand for the digitization of the archive. We acknowledge that memory-culture and historiography are not fixed points and therefore aim to create a situated memory practice that expresses a fluidity and diversity that can be addressed through artistic and curatorial research and practice. Continuing these tasks requires a shift in narration and the development of a new decolonial methodology that attends to the gaps in the association’s imperial archive, within which methodologies of proximity and engagement with archives are actively applied. At the same time, there is a significant amount of speculation involved in the work of assembling what is left in the archive, which opens the process. Speculation can be a tool of worldmaking and the bridging of inherently fragmented identities. It projects what could have been, or what could be.

Saidiya Hartman’s notion of critical fabulation has informed how we are aiming to move forward with the VBKÖ archive and our research project “Anonymity and Absence.” Hartmann suggests the potential for “critical fabulation,” which is based on archival research and a critical reading of the archive, put into practice by speculating about the inaccessible, silenced voices of the past, voices that “tell an impossible story” while simultaneously amplifying the “impossibility of its telling.”8 What she refers to are gaps in the transmission of the archive and the absence of an actual representation of personhood. She asks: Is it possible to exceed or negotiate the constitutive limits of the archive?

Within our expanded research and working with the VBKÖ archive, we collaborated with artist Onyeka Igwe, which added a physical layer to our inquiries. Igwe’s artistic approach of critical proximity suggests a coming close of one’s own body to the body of the archive through touch, dance, text, projection, and readings – thus seeking to account for how an archive becomes an embodied experience through closeness. Through this closeness, the cultural production of the colonial imagination can be examined in order to think through the application of the colonial imagination in something of an embodied with-ness in distinct temporal space. This approach applies an embodied practice as a way of working with that combines historical and archival research with critical theory and fictional narrative to make productive sense of the gaps and silences in the archive.

Both approaches of critical fabulation and proximity engender speculations on missing voices, narratives and objects that retain the violence of erasure and censorship. Performance practices, through their equally ephemeral and temporal qualities, enable an in-depth exploration of archives and provide a starting point upon which to examine the potential of decolonial and feminist archival practices while moving back and forth across the intersection of the “archive-as-source” and the “archive-as-subject.”9

Installation view of the exhibition “Archival Sites of Speculation: Storying the Silence,” VBKÖ, January 11 to February 11, 2024. Courtesy VBKÖ. Photo: Daniel Hill

The research project “Anonymity and Absence: Archival Sites of Speculation” has also enabled us to bring together artists’ workshops and an exhibition to create experimental sites within which methodologies of proximity and engagement with archives could be tested. Workshops, films, and works by Onyeka Igwe, SKGAL (Secretariat of Ghosts, Archival Politics and Gaps), Maryam Tafakory, Alessandra Ferrini, Mai Ling, Elske Rosenfeld and Olia Sosnovskaya functioned as tools for speculating, learning, and experimenting with artistic methods that approached the research questions. The various workshops and sharing practices were framed through a year-long seminar called Working the Archive (2022/23), which included students from the University of Applied Arts Vienna, who, as participants and invited artists, also added different positionalities to the exhibition “Archival Sites of Speculation: Storying the Silence,” aptly held in the VBKÖ exhibition space.10 The artists in the exhibition sought to envisage what was missing from documentation, testimony, or historical material preserved in various archives, and to give material form to ways of contesting dominant narratives and making way for other stories to be told.

Footnotes

- Panashe Chigumadzi, “Hearing the Silence” in Surfacing: On Being Black and Feminist in South Africa, ed. Desiree Lewis and Gabeba Baderoon (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 226–238.

- This project is supported by the University of Applied Arts Vienna Program for Inter- and Transdisciplinary Projects in Art and Research (INTRA).

- For further information, see an interview collaboratively written by VBKÖ members describing its 113-year history through both the emancipatory turn of the women’s artist movement in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century and the dark and complex period of National Socialism and its aftermath. Nina Hoechtl, Mika Mayurama, Stephanie Misa, and Julia Wieger, “Speaking with Gaps and Silences in the Vereinigung bildender Künstlerinnen* Österreichs (Austrian Association of Wom*n Artists): Introduction and Interview,” in Erasures and Eradications in Modern Viennese Art, Architecture and Design, ed. Megan Brandow-Faller and Laura Morowitz (New York: Routledge, 2023), 240–254.

- Julie M. Johnson, The Memory Factory: The Forgotten Women Artists of Vienna 1900 (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2012), 268–335.

- Johnson, The Memory Factory, 278.

- Nina Hoechtl, Mika Maruyama, Stephanie Misa, and Julia Wieger, “Speaking with Gaps and Silences in the Vereinigung bildender Künstlerinnen* Österreichs (Austrian Association of Wom*n Artists): Introduction and Interview,” 243.

- “Critical Closeness: A Conversation on Archival Work” was a panel discussion and film screening event held on October 18, 2022 at MUMOK (Museum of Modern Art Vienna) accompanying “Collaborations,” a discourse and performance program curated by the Austrian Association of Wom*n Artists (VBKÖ) with Onyeka Igwe, Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński, Sekretariat für Geister, Archivpolitiken und Lücken, SKGAL (Nina Hoechtl and Julia Wieger) and moderated by Stephanie Misa.

- Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe, vol. 12, no. 26 (June 2008): 1–14.

- Ann Laura Stoler, “Colonial Archives and the Arts of Governance: On the Content in the Form,” in Refiguring the Archive, ed. Carolyn Hamilton et al. (London: Kluwer Academic Publishers), 83–100.

- The exhibition “Archival Sites of Speculation: Storying the Silence” was held at the VBKÖ from January 12 to February 11, 2024. It included works by Katharina Birkmann, Maja Bojanić, nathan c’ha, Mark Chehodaiev, Alessandra Ferrini, Onyeka Igwe, Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński, Ivana Lazić, Arina Nekliudova, Carmiña Tarilonte Rodriguez, Elske Rosenfeld & Olia Sosnovskaya, SKGAL (Nina Höchtl, Julia Wieger), Tsai-Ju Wu, Lorenz Zenleser and was curated by Georgia Holz and Stephanie Misa.

Georgia Holz is an art historian and works as an independent curator, author, and editor. She is a senior scientist at the Department of Site-Specific Art at the University of Applied Arts Vienna and formerly held curatorial positions at the Generali Foundation in Vienna and Kunsthalle Wien. She is on the board of the Kunsthalle Exnergasse in Vienna (WUK). Her interests focus on artistic and curatorial gestures that question and deconstruct hegemonic narratives by means of “parafictional” and speculative strategies. She is engaged in critical artistic practice with archives and leads “Anonymity and Absence: Archival Sites of Speculation,” an interdisciplinary research project at the University of Applied Arts.

Stephanie Misa is a visual artist and researcher whose work centers around decolonizing methodologies. She consistently follows her interest in complex and diverse histories through her various multimedia installations and performances. Her artistic practice connects multicultural collaboration, curating, and feminist criticism. Recent projects include the 9th Bucharest Biennale (2021), solo exhibitions at KODA House, Governors Island NYC (2022), RMIT Gallery, Melbourne (2023), Kunstraum Lakeside, Klagenfurt (2023), and the Mai Ling Collective exhibition at the Secession, Vienna (2023). She is also part of “Anonymity and Absence: Archival Sites of Speculation,” an interdisciplinary research project at the University of Applied Arts.