Transversality: What Slips Away While Moving Toward Common Becoming

Marc Herbst

January 2023

Our collective living through the Covid-19 global pandemic demonstrates one way for the performance of living through the climate emergency – with reduced margins, tighter restrictions, and a common desire to maintain a kind of status quo. Yet, decreased margins actually mean increased marginalization, affecting those people that the powerful identify as “simply” the victims of natural events. While the terms under which the wealthy live continue to tighten and more places and ways appear to become unlivable, more and more people live under all kinds of impoverishment. Status-quo continuity normalizes refugees dying in Arizona’s deserts and drowning in the Mediterranean, alongside the sixth great mass extinction.1

While this status quo utilizes laws, police, and social norms to maintain order, political and ethical thought challenges us to expand upon the edges and margins for how we live together on this changing Earth: to transversally (and generatively) make space for each other in ways different than those that expand space for individualistic impoverishment. Thus, with the limited material margins that our world offers us, transversal changes are those surprising social transformations that occur through unexpected and unforeseen ways, toward ends that go against government accounting. Transversal thought highlights other ways for being to move through these margins. Transversal movements multiply possibilities.

To attend to transversal change is to attend to transformational methods – to ways of relating that are not accounted for by the current order. While exploring transversal change is the subject of this essay, it is important to first look at what maintains the apparent order despite the always-changing nature of our world. Dominant political and social infrastructure scaffold purported truths of our situation, which is actually in constant flux. There are droughts and floods, wars and market downturns. Yet, the dominant infrastructure’s ability to continually explain itself as useful somehow maintains its centrality. “The invisible hand of the market” (and its partnering dominant social forms) is that stacked deck that modern governance utilizes to explain social orders that generally preexist entanglements of power as infrastructure. This hand is positioned as “natural” where the “natural hand” obscures and normalizes governance and capitalists’ economic and libidinal (desire, attention, and investment) interests that are effectuated simply as “natural” economic activity. The investments of the wealthy are often protected by the idea that they have a “natural right” to spend their wealth as they simply desire; as investments, as interested stakes, as pleasurable and profitable personal activities. Through the force of this “hand” and its accounting and evaluating systems (price comparisons, cost-benefit analysis), this economic order stifles the otherwise overwhelming potential of human sensitivity, desire, potentiality, and creativity to do things differently. In other words, money – the pressure to earn it and the attention that comes with its potential reward – seems to keep things in order against our actual capacities to do things otherwise.

However, in seamless contradistinction to the interests of the economy, throughout the Covid-19 pandemic governments acted to limit profit motive in order to balance competing demands; for example, through laws against hoarding toilet paper and respirators.2 To maintain the system, laws are written and funds disbursed to manage the complex social underpinnings of that which appears to just be economic affairs. So, the state allows itself a capitalist economy or laws to maintain order, in order to silently manage the ongoing transformation of the world’s climates: economic climates, social climates, political climates, ecological climates. Of course, this management is simply about managing the appearance of normalcy while the actual world continues to burn.

The assertion made by both neoliberals and neoconservatives regarding the “unnaturalness” of governmental intervention demonstrates the evident truth that any and all infrastructures, laws, and economies are not the result of natural selection. Governmental force is “positively” played out by its shepherding economic and thus social activity while governmentality is “negatively” enforced through laws and financial penalties and backed up by the threat of physical force. Ultimately, governmental force is the shadow cast by “the invisible hand” that purposefully manages the status quo.

Through whatever means, governance could simply intervene to address climate issues. But in practice, the West lives within a system of governance that is also simply a collective expression of the libido of rich fucks – expressions successfully translated through social, cultural, economic, and democratic processes. So, in this context, we can call “transversal” any process of change that doesn’t simply play through the interests of a few rich people and their political orders; a process that doesn’t say, “We must protect profits at all costs.” Transversal is the name we can give to ways for transformation that do not operate under this economic and legal status quo. Transversal is not actually a “thing,” it is just a nominative description for what appears to be a surprising change or social innovation – surprising because it goes against the governing order. “Transversal” is a name given to transformations that are hard to initially grasp because these changes are made through barely noted social and cultural affection. By “noted,” I mean, poetically, that while our days overflow with a variety of relations and experiences, feelings and interests, only a few matter in ways that are remarked upon, accounted for – even literally paid for or noted for systemic function. All the rest is dark matter, undercommons, the “merely” social. Alliances, interests, loves, solidarities, meanings, practices socially organized without notice. This is the realm of the transversal.

Transversal transformations are generally conducted through immaterial effect rather than tangible infrastructure and standard accounting procedures – that is, through known routes. As the world changes, it is important to remember that though all things that are solid melt into air, our ability to relate to things that were once tangible, actionable, material but now have disappeared remains, regardless, through memory. Inside, the heart and mind find ways to connect to memories, but also new concepts, new relations, new meanings. We build desires and attention and fulfillment over time. When we lose something, we can find something that replaces it.

Through their ability to mediate meaning and model emotions, art and culture have the ability to orient immaterial relations between individuals and things3 – so, art and culture are unusually capable of driving transversal work.4 Art and culture facilitate psycho-social relations between things and people; it can be that meaningful object to relate to or it can provide suggestions for how to manage relations. As such, transversal art or culture is both a means to relate (in how a singer sings about a new love for the lover or the general audience) or stands as the thing to relate to (by being something, e.g., a James Turrell installation, a cheddar cheese sandwich). As such, transversal is as much a verb as it is a noun.

Transversal is a term rooted in mathematics, describing a line that crosses others. It was utilized by Félix Guattari in his psychological work at the La Borde mental health clinic in France to name the purposeful work of supporting surprising change in individual patients’ habits and routines.5 I associate the term with the European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies’ (EIPCP) multilingual website and journal Transversal, which began publishing around the turn of the millennium. Transversal began theoretically exploring the possibilities for critical/creative/political cultural practice in Europe after the end of the Cold War. EIPCP was enmeshed with Europe’s late 90s/early 2000s creative alter-globalization movement’s left-wing challenges to the EU’s neoliberal order and found solidarity with the EuroMayDay’s efforts to revivify a post-Cold War emancipatory communism.6 Today, I find the word transversal useful in identifying a conceptualization of how cultural activity can transform fixed habits through ways different from governmental action and its top-down logistics, and thus manage the monstrous problems we face as our global climate transitions toward bigger catastrophes.

Finally, a note regarding art’s transformative capacities, especially in the context of this arts journal. Art is involved in a cat-and-mouse game with capitalist development.7 Since the Situationists, “avant-garde” art has been understood as being captured by the art world’s capitalist modes for reproducing itself so that where fine art actually drives meaningful, transformative change, these changes must be understood as nothing other than a system error. Nevertheless, art’s transformative capacities lie in its attention to the affective sensibilities of governing institutions and attentions that are constituted by the political and economic systems that capture it. For artists, transversality might be an important concept to wrestle with because it desires to move meaning, and thus cultural activity and social organization, beyond the art world’s grips.

Transversality understands relation and being as entangled in and defined by one another. Further, transversality understands being as fixed but its meaning as gracefully flexible. Drawing by the author.

MEANINGFUL RELATION

In Newtonian physics, there is nothing new under the sun. Despite modernity and capitalism’s claim that the human world exists outside of nature, our world is mostly a closed ecological system. Our changing climate demonstrates how capitalist development comes at the unaccounted expense of the rest of nature, and also through the death, displacement, and unlivable conditions for generations of millions of poor people around the world. Despite this, the massive changes in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries were understood to have come with few costs – even though conveniences like indoor heating and refrigeration come at the expense of a trashed planet.

In contrast to changes that marginalize all costs, transversality embraces what adrienne maree brown names “emergent strategies,” ways of change that can be understood as transformations built upon what already exists in the world around and within us.8 The notable but incomplete US civil rights movement demonstrates how social transformation is made through affective provocation and ethical development from within preexisting societies. While change is contingent on what exists, its potential comes from relating differently to what already exists. Note how the utilization of fossil fuel changed the way we related to travel, time, and speed. Speculate on how Carolee Schneemann contributed to a different way of relating to one’s own and others’ bodies. We can interpret how an image of a frog might relate to a window, or a Roman numeral to the kitchen. You see, most people can relate to most anything, especially when art and activism clarify how we might relate.

Culture is defined as the aspects of things that orient understanding or facilitate relation. Thus, the way that culture exists to make it so that things in the world can relate – regardless of how the relation is accounted for (as property, as a father, as the subject of a cultural studies paper) – is central to an understanding of how transversal aesthetics manage to move meaning and thus move further cultural activity and social organization outside the grip of power. Things involved in strangely transformed relations are moved into new relations through routes and methods that transgress norms and routines. They transgress normal measures of meaning, value, time, space, etc. that would otherwise constrict relation. To step beyond normative relational constrictions is to more broadly, affectively, engage with life’s terms; terms that marginal peoples often have greater experience working with and through. When we stay within the norms for meaning and sustenance, we transgress nothing; when we must seek to relate differently, we find new ways to be.

Overall, the possible archive of all worldly human experience and our own worldly sensations exceed our possible accounting of what we sense and know and can say; a picture may be worth a thousand words, but nothing is denser than experience, and transversal relations are relations that are not normally ascribed. Transversal change is relational change that occurs at a scale that drives political change from outside the margin of the norm, as I discuss with an example below.

THE SUBJECT AND/OR OBJECT OF THINGS IN TRANSLATION

To think about transversality suggests a methodological way of working toward ends that academic disciplines can’t describe – not because disciplines don’t structure meaning, but because they do. I conducted research with the Barcelona-based Plataforma de Afectadas por la Hipoteca (Platform for People Affected by Mortgages – PAH), a social movement that illustrates how undisciplined relations can have a radical effect on the actual world. That PAH was able to change common-sense understandings regarding the right to housing and then remake actual housing law demonstrates how unexpected occurrences can seem like the effect of social magic. Yet, rather than magic, this change is simply the result of new relationships forged in surprising ways. In the case of PAH, change was moderated through established things in preexisting contexts that were made to be understood differently through activist and aesthetic work. While investments, police, logistics, and law provide a steady supply of relational information for state stability, transformational relational work changes the rules for what is considered stable. In this case, the state wanted preexisting relations to stabilize the banks, while social movements wanted to stabilize housing.

With the highest home-ownership rates in Europe by 2006, Spain’s banking and housing system developed as a way to privatize public debt. The system had operated for about fifty years, with banks consistently let off debt’s hook since Franco’s fascist rule. Because of home ownership’s central role in Spain’s political economy, Spain’s laws made it virtually impossible for debtors to escape debt. So central was home ownership in the country that when the 2007–2008 financial crisis hit, most people from across Barcelona’s society – rich and poor, people from migrant and non-migrant backgrounds – were affected.

Ada Colau and Adrià Alemany, Mortgaged Lives, English translation by Michelle Teran (London: Journal of Aesthetics & Protest, 2015). [PDF]

Though not a mental health group, Barcelona PAH members were provided with access to weekly art and group therapy sessions to learn how to deal with the emotional trauma of their situations. Working with explicit psychological needs was only part of PAH’s remit. Transforming shared sociality was another. Their media strategy was coordinated to represent the group’s diverse membership in a way that no one seemed marginalized – rather, all their press photos and their activist campaigns were coordinated to make its members appear as relatable people challenging unjust laws. This image contributed to a key factor of their eventual success: their massive popularity and the public support for their activity.

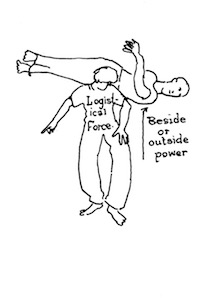

Transversality suggests that a bottle can become a microphone. Drawing by the author.

Many PAH protests were carefully choreographed, and one protest training I witnessed stood out. The group was debating the values they should demonstrate through the protest activity. Their deeply ethical conversation involved how to express individual and collective anger, and the group’s diversity was reflected in the range of opinions. In order to establish a talking order, the discussion moderator suggested they use a microphone. There wasn’t one around, so a plastic soda bottle was virtually transformed into a microphone. The bottle’s usual liquid-holding capacity was diminished in favor of the fact that it could appear like an object (a microphone) that conveys social attention. Meeting attendees listened to the person with the bottle as though it were a mic. This simple transformation succinctly illustrates how reality is subject to social expectation and is not quite tied to actual materiality. It demonstrates how the production of new social meaning can reorganize ways that people manage to work together. Relations between people, and between people and things, may look like immutable facts but can be bridged by object-oriented interventions or via more purely relational social processes.

To attend to transversal aesthetics is to attend to the variety of entangled properties internal to things involved in the relational common – the commons which decolonial scholar Denise Ferreira da Silva characterizes as the “fields of difference without separation.”9 This commons within which we relate, this commons of sense, operates like any other commons. In this commons is where so much transversal work happens. Conceptually, that this space is commonly accessible makes it useful for the conception of new ways to relate. In PAH’s case, a new place of common sense was established through ideas that played out in public protests, and that was registered over time in the public sentiment by the accumulation of posters, stickers, Facebook posts, etc.

ORIENTATIONS OF ENTANGLEMENT AND TRANSVERSAL MOTIONS

Another lesson of PAH is that though several of its activist founders had been working on the topic of housing for years, it was only when their knowledge was paired with an actual crisis that something could actually change, radically. Knowledge of a thing, in this case, an awareness of the housing market’s instability, is often not enough to drive radical change. Like how the tarot deck randomly archives any variety of human passions and activities, transversal aesthetics stand in the ready to relate to actual human passions that are embedded in structured realities that must desire to move toward different ends. So, to the extent that our current condition is described as an anthropocenic ecology of dwindling resources toward end-time horizons, non-transversal social processes keep us committed to conditions that are already on a death march. The critical politics of working transversally is to recognize relational patterns and habits and find ways to reorganize socio-cultural scaffolds that organize things more sensibly.

There is nothing new under the sun; in the recesses of our common being are seeds for other ways of doing and being. Other knowledge and perspectives remain entangled within lives that otherwise seem copacetic with our capitalist accounting and world-ordering system. Dominant ordering systems impress their preferences upon how we should act and what our sensing bodies and flickering minds should focus on. Transversal aesthetics prioritize other affects and items, utilizing those aesthetics besides the actually flexible human capacity to comprehend and relate differently in order to determine other ways and matters. In the recesses of our silverware drawer, we can discover the spoons next to the forks, and we can utilize them both when necessary.

Editing a journal that purposefully situates itself adjacent to social movements as much as to academia or art worlds, I’ve seen how political artwork and critical theory move in counterintuitive but systematically predictable ways. The relational path that things take in the world directs their and also the world’s development; that socialist architecture doesn’t spontaneously combust in a capitalist world and that the concept of Christian charity can exist within fascist states demonstrates that counterfactual qualities can coexist: that seemingly smart people can have some bad ideas, that bad things continue to exist in good systems. Reality is not ideology, on its own. East Germany’s legacy architecture in capitalist Berlin does not have the relational power to cast off the worker’s chains.

Claudia Firth, Marc Herbst, Robby Herbst, Amber Hickey, eds., “Culture Beside Itself,” Journal of Aesthetics & Protest 11 (Leipzig: Journal of Aesthetics & Protest, 2020). [PDF]

Editorial art from Journal of Aesthetics & Protest 11, “Culture Beside Itself.” Drawing by the author.

We asked the critical theorist of the printed word Nick Thoburn to analyze how the submitted newsletters resonated with their sites. In the subsequent interview, Thoburn utilized Rosalind Krauss’s concept of “bagginess” to describe a particular way that these newsletters’ contents functioned within the visual and physical reality of their words and printed matter.10 Generally, Thoburn characterizes the newsletter as groping and self-reflexive. From Santa Cruz, California, the self-organized DSA Santa Cruz Ecosocialist working group’s newsletter groped with fixing their self-relation to California ecology, almost as a way to ground themselves. The collective @ .ac newsletter, which was handed out on a picket line at the University of Lancashire, is looser in its style, literally playing with the form of their collectivity and turning their relations into an aesthetic game. The We (TBD) collective’s newsletter, distributed at the end of their gallery exhibition, is very baggy; it discards newsletter conventions and simply stews in the emotional fluctuations of their being together. All these newsletters demonstrate how conceptually limitless capacities for autonomous collectivity always necessarily appear as nuanced and limited by the margins of their own composition. That is, the snapshot-in-time nature of newsletters makes them images of their own institutional becoming – and the conceptually limitless ambitions of their members and community can only be viewed through the actual limited institutional capacities of each newsletter’s formal appearance.

For this issue, we also interviewed the Out of the Woods eco-theory collective about the burdens that governance places on autonomous collectivity. They discussed the unsustainable demands that governmentality places on its populations – identifying government’s political and psychological ordering through its prioritization of white children. Their attention to the white reproductive imaginary “precludes building queer forms of kinship beyond the heteronormative family . . . and unnecessarily steers us away from the capacious forms of relationality and care we will need to survive and flourish amidst increasing and cascading crises.” Capacious relationality, in no relation to governmental burden, defines the space for transversality.

Cover of Everything Gardens!, edited by Marc Herbst and Michelle Teran, design by Luca Bogoni. [PDF]

ON TRANSVERSAL MEASURES: OTHER TEMPORALITIES

Transversal aesthetics are processually ethical and nuanced; that is, they are situational and depend on context. I witnessed this contextual play as a member (2014–2016) of The Field at New Cross community space, which utilized relational and performative practices like deep listening and Gestalt therapy to develop an open conviviality across social divides. The goal of these relational practices was to experiment in a collective process of social becoming, to learn how these diverse groups could meet each other’s social and thus political needs in ways different than what the individualistic and market-based culture of neoliberal London offered. The miasma of London’s neoliberal context made every angle of The Field’s activities open and vulnerable to endless dissensus. From inside the group, it is easy to blame the group’s eventual failure to socially communalize South London on individual collective members’ shortcomings, rather than London’s insufferable cost of living and hyper-individualistic ethos.11

More recently, I’ve been working on a learning project situated in the experimental Prinzessinnengarten garden in Berlin. Despite its ongoing conflicts, we gave ourselves a reprieve from some of the brutal pressures of neoliberalism by organizing for ourselves in the luxurious shadow of the garden’s 100-year lease, the time frame we have to get our relations in order. We move through this temporality with a collaborative educational project, the Nachbarschaftsakademie, which aims to situate and support cosmo-politically open relations defined by eco-feminist and decolonial sociality. For the 2019 Nachbarschaftsakademie summer school initiated by Åsa Sonjasdotter and Marco Clausen, research professor Michelle Teran and I coedited a book, Everything Gardens! Growing from the Ruins of Modernity, that initiates our learning across these scales of time. The book’s foreword begins:

By the time you read this, the Prinzessinnengarten will have its 99-year occupation clarified by the city. Our political desire to claim this fact is built upon our understanding that to meaningfully curtail capitalism’s ecological and social violence, there must be a total spatio-temporal rearrangement of things, here and everywhere. EVERYTHING GARDENS! FUCK YOU.

Here, collectively, it is as though we have allowed ourselves to be suspended in time. And the ether that affords and organizes this suspension is that mix of our individual personal economies, the organizations we are staggering to put in place and our collective political desires for many different things to come to pass. The Prinzessinnengarten’s occupation is one of these things. It is also that time-traveling geographic fact that manages to contain all this suspension.

This book, focusing on the garden, was intended to be written in stone and be authored between time. Within the folds of this binding are analysis, documents and the luxury of errors we allow ourselves to make because, though the contours of the future are unknown, we do know ways we’d like to get there.12

Stones are subject to different temporal expectations than dancers. Image by the author.

The book contains a glossary of words; the glossary is glaringly incomplete, for while it has many words, it has very few definitions. Our editorial decision to publish this glossary was to demonstrate how words are also just works-in-process. Meaning is developed over the course of time and measured in context. The luxury of the 100 years of learning we have afforded ourselves is the grace of knowing that our limited and inadequate efforts will have the ability to eventually add up.

All systems, capitalism and patriarchy included, have specific measures to identify what is notable and what relations can be attended to at the expense of others. Capitalism says, “Value that which drives individual monetary profit,” and patriarchy says, “That which benefits the father.” Transversal efforts work through other collective measures. So, when we generously build relations toward non-capitalist and non-patriarchal ends, we may be caring for relational connections that allow different things contingent to those relations to manifest.

In relation to conflicts in the Prinzessinnengarten, Michelle Teran and I began a research project on how dream-time apprehensions of reality facilitate an appreciation of the totally entangled nature of collective social relations. We began looking at the social composition of sleep-time dreams and began workshops that used collectively shared bedtime activities (such as storytelling and reading) to set up workshop participants to dream through specific social questions that have been vexing the attending group.

More so than words, dreams may represent the complex ways each of us relates to the complex world through singular moments’ expressions. Dreams trace an individual’s attentive wandering over their day and demonstrate the many ways we can build meaning. No one interprets a dream by how much an imagined car is actually worth, and no one has been imprisoned for laws they silently break in their dreams. Yet despite the totally lawless and immeasurable nature of our subconscious, this is where we each build meaningful connection to the world. Ultimately, a surrealist appreciation for what anchors us to our values also helps facilitate an appreciation of how art and culture ground transversal transformations toward the horizons that we must develop in order to establish and continue convivial life through these rough times.

Dreams may demonstrate the overflowing nature of meaning and doings that fill our day-to-day. Dreams demonstrate some of the psycho-social bridging that each of us do between things, and that can be done as socio-political work. Transversal aesthetics facilitate this taking care of the world and its relations that exist, while also saying fuck you to the governing forces that limit the generative, possible, and nurturing ways we can better relate.

Editorial art from a flyer produced for Michelle Teran and Marc Herbst’s summer 2021 dream workshop, “To Sleep in Comfortably in Common (which is politics)” at Floating University and the Prinzessinnengarten, Berlin. Drawing by the author.

Footnotes

- For more on the accelerating rate of extinctions today, which is often referred to as “the sixth great mass extinction,” see Deena Robinson, “Sixth Mass Extinction of Wildlife Accelerating – Study,” Earth.org, August 20, 2021, https://earth.org/sixth-mass-extinction-of-wildlife-accelerating/.

- Of course, there was a limit to government responses, but with so many years of welfare cuts, austerity measures, and free-market ideology, I am drawing attention to the fact that governments doled out during the pandemic in unimaginable ways. For example, due to the so-called “child tax credits” in the US, the child poverty rate dropped for the first time in quite some time. See “New Data Show That the Child Tax Credit Fueled a Substantial Reduction in Child Poverty,” Annie E. Casey Foundation, September 19, 2022, https://www.aecf.org/blog/new-data-show-that-the-child-tax-credit-fueled-a-substantial-reduction-in-child-poverty.

- The word “thing” here is used to mean any material or immaterial thing or concept. The nature of things and their capacity to be unique – and to be also an idea and also thus a part of a class of things and not unique – has long been thematized within philosophy. These debates, going back to the Greeks, ask about the unique nature of (for example) this stone, that stone, or the word “stone.” These debates notice how this stone might have definitional qualities that are absent in that stone – for example, one might think of a stone as hard, though some stones are very soft. While the literature on this is deep, I initially came to philosophical discussions on the topic through Giorgio Agamben, The Coming Community (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993).

- Here culture is understood, in the anthropological sense, as the human face of anything. Through its human face, a rock can be as cultural as a concert hall, a doorway, or your friend. This human face allows “us” to identify the thing as a rock, to understand anything for what it is, does, or might do. The human face tells us how to relate to it. Art here is understood as a smaller subset of culture – what we might understand as production related to the “art world” and subject to that world’s Western-dominated conversations around meaning and to its modes of actual and meaning-oriented distribution.

- Félix Guattari, Psychoanalysis and Transversality (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015).

- EuroMayDay began in Milan in the historic activist year of 2001 – concurrent with the rise of the alter-globalization movement. A small “c” communist movement with an implicit critique of fossilized Left organizational strategies, it focused on precarious workers and their struggles. It made headlines throughout the activist world for its innovative analysis and aesthetics that played with religious and labor themes. Like others associated with the alter-globalization movement, EuroMayDay utilized a “protest-as-roving-street-party” model of moving through urban space in unique ways. This form for celebrating May Day blossomed in the early 2000s, and wild May Day parties occurred throughout Southern and Central Europe in this period.

- See, for example, Max Haiven, Art After Money, Money After Art (London: Pluto, 2018); Josephine Berry, Art and (Bare) Life (Berlin: Sternberg, 2018); and Kerstin Stakemeier and Marina Vishmidt, Reproducing Autonomy (London: Mute, 2016) for recent examples of writers dealing with the commodity nature of artwork in how it tends to dominate artwork meanings against all other possible meanings.

- adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds (Oakland: AK Press, 2017).

- Denise Ferreira da Silva, “On Difference Without Separability,” Incerteza Viva: 32nd Bienal de São Paulo, ed. Jochen Volz and Júlia Rebouças (São Paulo: Ministry of Culture, Bienal and Itaú, 2016), 57–58.

- Thoburn writes, “If, on the other hand, publishing ventures foreground and interrogate the open-ended mesh of publishing forms, process, and relations, then publishing materiality becomes an arena of critical practice in its own right, no longer corralled by its textual content.” Here, Thoburn identifies a tension between the explicit nature of newsletters as a temporarily closed but serial object. He then discusses how many of the submitted newsletters nevertheless buck against the limits of the form. He writes that if the newsletter (or any other thing) “becomes self-reflexive about its publishing materiality beyond clichéd manifestations, then the relation between its ideas and wider materiality takes shape, as I understand it, as a baggy fit. It’s an approach I develop from Rosalind Krauss’s wonderful formulation that certain artworks take form as ‘self-differing mediums.’” See Rosalind Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000).

- Some of the noteworthy self-focused psycho-social work that The Field undertook is documented in a book published by Canary Press, a collaboration of the Minneapolis-based Beyond Repair Project and the Journal of Aesthetics & Protest. See Toby Austin-Locke, Paolo Plotegher, and Rosanna Thompson, eds., The Process of The Field in New Cross (London: Canary Press, 2019). Available at: http://thisisbeyondrepair.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Interior-Field.pdf.

- Marc Herbst and Michelle Teran, eds., Everything Gardens! Growing from the Ruins of Modernity (Berlin: nGbK/ADOCS, 2020), 11.

Marc Herbst is co-founder and co-editor of the Journal of Aesthetics & Protest. He is an interdisciplinary researcher/editor/artist that appreciates the idea of arts-based research. He favors collaborations and situated projects. In his teaching and research, he often utilizes movement and play-based methods, exemplified by his work collaboratively building monuments and museums of climate change with kids in playgrounds and summer camps. He is a member of the nGbK SALT. CLAY. ROCK. curatorial collective looking at nuclear pasts and energy futures, and works with The Ghost Host foundation. He is currently a Castille Fellow for Anthropology at Whitman College.