Trust Exercise: Group-Think Rewrites Protocols of Protest and Consent

Jenny Wu

September 2021

“The classroom is a semiprivate room. As such, it is a site of the peculiar intimacies and coercions, the self-revelations and decisive constraints, that characterize a space neither public nor private, both exclusionary (perhaps even exclusive) and impersonal.”

–Ellen Rooney, “A Semiprivate Room”1

For a long time I began the writing workshops I taught with this quote by the literary theorist Ellen Rooney in order to point out, not without a hint of irony, the outsized authority that a teacher in a classroom possesses – not only over how or what knowledge is disseminated to a group of people with mixed backgrounds and experience, but also over how these people in the room comport their bodies, how they react to stimuli, whether they feel safe, nervous, self-conscious, or energetic. By affixing an ambivalent epigraph to the tops of their syllabi I was perhaps also trying to acknowledge what I had experienced coming of age in the American public school system where mental and physical exertions is made compulsory, by curricula and culture, in a style that bordered on, if not was, coercion: running laps, having your abilities tested in public, changing in front of others, having your clothing policed by a dress code, and so on. In 2012, the year I graduated high school and left the world of compulsory coercive education, cultural critic Maggie Nelson published The Art of Cruelty, the book through which I was introduced to (among other items of interest to a young woman craving and confused by discourses of violence and consent) the conceptual artist Stine Marie Jacobsen (b. 1977) and her film Do you have time to kill me today? (2007-09).

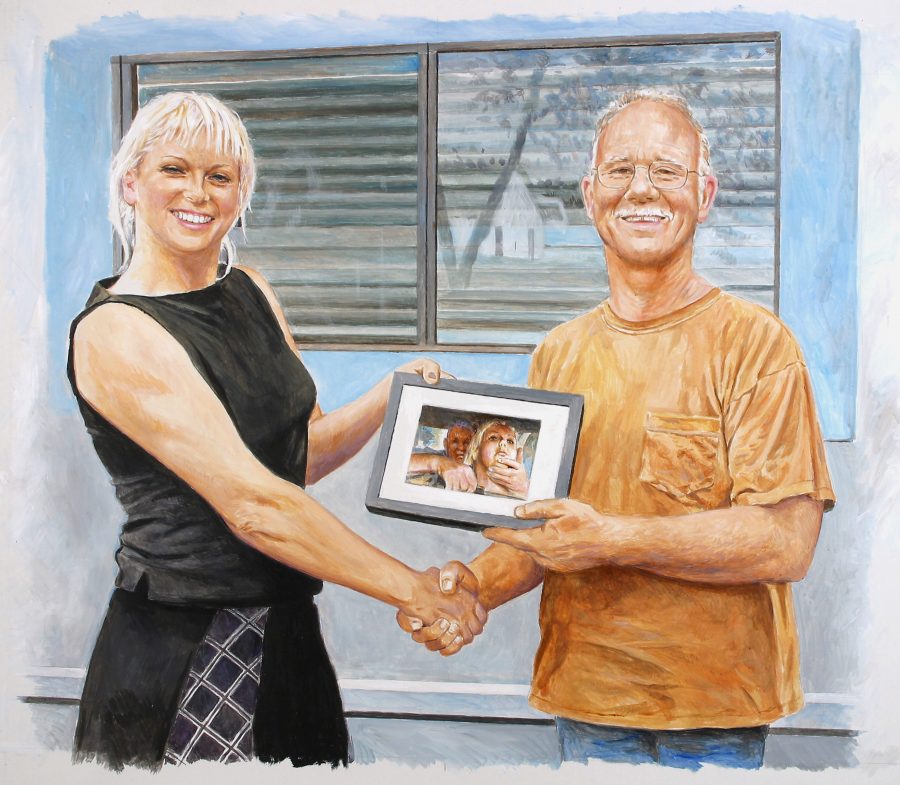

Over the course of two years, Jacobsen had filmed a “roleplay” with her male neighbor, who from the backseat of a car pretended to cut her throat with a prop knife as she drove the car. In The Art of Cruelty, Jacobsen’s film was used to illustrate the “unruly effects” that elude consent in a chapter titled “Nobody Said No.”2 Recently writing to me in St. Louis from her home in Berlin, Jacobsen recalls debuting the film during her formative years as an art student. At the start of the project, her neighbor had been reluctant to “kill” her; after about seven takes, however, he transformed into an enthusiastic – even angry – “killer.” A faculty member at CalArts warned Jacobsen that a profound psychological shift had occurred in her neighbor after repeated participation in her roleplay. However, now given the longer trajectory that Jacobsen’s artistic practice has taken, it is easier to see that more than an exploration of victimhood, conditioning, and trust, this early conceptual work displayed a keen understanding of the ways in which interpersonal interactions are undergirded with procedural contracts, as well as the way these protocols are created, enacted, and, at times, violated.

“I used to perform a lot between 2003-09,” Jacobsen tells me, “but I didn’t like to be the center of attention, so I gradually started working with other bodies, mostly in front of the camera. Then when I was introduced to the work of Artist Placement Group and Group Material, my practice really turned participatory.” Jacobsen continues to be interested in (re)enactment and protocols (and, in general, ongoing projects that don’t necessarily culminate in an art “object”), and her most recent work, Group-Think (2020), seems to have found a sweet spot at the intersection of protocols and consent. In other words, her conceptual pieces deftly examine if, when, how, and to what end specific – often vulnerable and revelatory – arrangements between two or more people are negotiated, implemented, and maintained.

Stine Marie Jacobsen. Group-Think, Manifesta Biennial 2020. Photo: Aurélien Meimaris

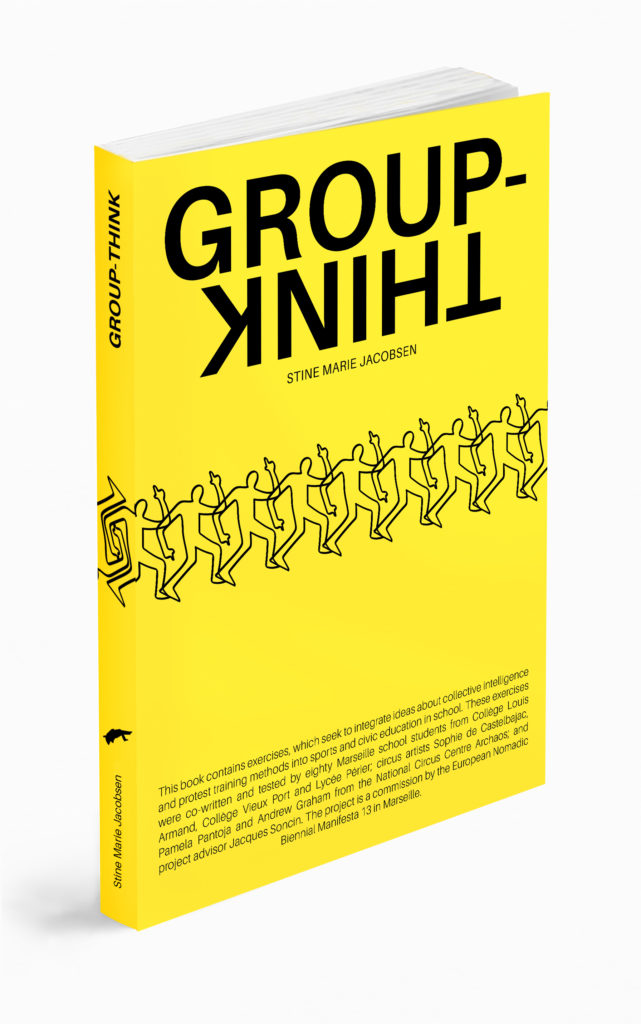

Commissioned by the European Nomadic Biennial Manifesta 13 (28 August – 29 November 2020) and made in collaboration with Manifesta 13 Education Department (Yana Klichuk, Joana Monbaron and project assistant Primavera Gomes Caldas), Group-Think premiered in Marseille, France, in the form of a screening on the rooftop of Coco Velten. The project as a whole is a sports and civic education program that takes place over a series of conceptual and physical exercises. These exercises were developed by Jacobsen in collaboration with the French contemporary circus Archaos and tested by students in several schools in Marseille. Today, Group-Think exists in the form of a pocket-sized bilingual handbook containing open-source instructions for participatory exercises and a film documenting the performance that was ultimately carried out by eighty school students from Collège Louis Armand, Collège Vieux Port, and Lycée Périer. Divided into six sections – Intro, Breath, Body, Aid, §, and End – the handbook encompasses exercises that help train young people to be comfortable and competent in a public gathering and to be aware of what kinds of physical situations to expect (e.g., getting pushed and pulled, having to use their bodies to communicate across large distances, etc.). According to Jacobsen, “Group-Think is a counterbalance to the police’s use of crowd-control kettling techniques, where they trap and detain, surround and drive protesters into a box, before making arrests.”3

Stine Marie Jacobsen. Group-Think, Manifesta Biennial 2020. Book design: Modem Studio & Stine Marie Jacobsen

The strategic exercises outlined in the Group-Think handbook – some of which are written by Jacobsen, some of which she found and modified, and some of which were given to her by others – combine sports and protest training to cultivate useful collective intelligence. In short, Group-Think teaches young people to “stay with the trouble,”4 instead of constantly looking to teachers for instructions. There are no winners in these exercises; instead, micro-colony behavior is the goal, which makes the participants stronger. Part of Jacobsen’s aim with this project was also to show young people that this can be achieved not only online but offline as well.5 Contexts that Jacobsen looked to while compiling the exercises include the Alexander Technique (1890s-), yoga, Buddhist walking meditation, the Surrealist practice of “exquisite corpse,” the German protest group Ende Gelände, and the Brazilian drama theorist Augusto Boal’s Games for Actors and Non-Actors (1992). One of Boal’s exercises Jacobsen cites directly is “Slow Motion,” which Jacobsen calls “Slow Run”:

Try to become the slowest runner. Once the race has begun, the group must never stop moving, and every movement should be executed as slowly as possible. Each runner should take the largest possible step forward on every stride. As one foot moves in front of the other, it must pass above knee-level. Another rule is that both feet should never be on the ground at the same time: The moment the right foot lands, the left foot must rise and vice versa. One foot should remain on the ground at all times.6

Like Boal, Jacobsen argues that because the exercise “requires considerable equilibrium,” it “stimulates all the muscles of the body.”7 However, Jacobsen takes Boal’s argument further by noting that the exercise promotes “a greater understanding of slowness as strength.”8 Collective strength is the opposite of what “groupthink” is stereotyped to be, which is a passive and uncritical deference to collectivity. By enacting a shift in the language, Jacobsen retools Boal’s exercises – as well as other known and proven techniques for expanding bodily awareness – in such a way that they help further the goals of present-day youth protest movements in Marseille and beyond.

Like Do you have time to kill me today? and other projects Jacobsen has organized such as Direct Approach (2012-present)9 and Law Shifters (2016-present),10 an important aspect of Group-Think lies in the way Jacobsen brings the political stakes of protocols and participation to the foreground, this time turning the semiprivate space of the school inside out and occupying its paradigms of group instruction to serve a public function. In many ways, Group-Think grows organically out of Jacobsen’s previous work with protocols, but the project also responds to the present moment in Marseille and the world. According to Jacobsen, in Marseille and France at large, beyond the yellow vest protests, young people have been protesting against the Macron government’s educational reforms. A large number of French minors, their teachers, and their sympathizers are protesting across the country in reaction to the simplification of the BAC exam (colloquially referred to as le bac) which prevents young people from Marseille from going to Paris to study and thus exacerbates social and structural inequalities in the country.11

Moreover, the right to assembly and protest is under threat as a natural civic right. According to Civicus data, Jacobsen writes, only 4% of the world’s population lives in countries where governments are properly respecting the freedoms of association, peaceful assembly and expression.12 In fact, while developing Group-Think, Jacobsen was advised by Marseille lawyer Élise Vallois that the French constitution does not address and guarantee the right to protest and assemble in public. Article 431-3 in the French criminal law, defines a crowd or group as illegal.13 According to Jacobsen, this criminalization of crowds, which do not possess the same fundamental rights that an individual does, is a phenomenon that can be witnessed in many countries today.14

It is against this political backdrop that Group-Think establishes its protocols and collective actions take shape. In a way, the sports education aspect of this conceptual piece is its camouflage; it is what allows the protest-related exercises to grow legs in schools where teachers may not be amenable to youths protesting. That Group-Think occupies the language of physical education was, for Jacobsen, “an easy step,” since both sport and protest were strong interests to the high school students of Marseille.15 However, the particular success of Group-Think is that it effectively turns what could be a competitive atmosphere into one of collectivity and cooperation. Physical education has a long and varied history dating back to the Greeks, throughout which there were certain pedagogues such as Friedrich Ludwig Jahn (of whom an enormous bronze bust remains in St. Louis’s Forest Park, occupying the site on which the German pavilion at the 1904 World’s Fair once stood) who imbued sports education with the values of nationalism and moral rectitude.16 Jacobsen, however, shifts the idea of physical fitness away from its nationalist, ableist, and individualist connotations toward an ethos of internationalism predicated on sensitivity, solidarity, and safety.

Most of the exercises in Group-Think – such as #5: Breath (“Talk to the students about how important breathing is. Breathing is the key to feeling calm and focused”) or #26: Louder Voice, which gives readers various vocal training exercises that amplify the voice – promote these values in a relatively neutral and practical manner, although there are a handful of exercises in the book that enact – potentially challenging – transactions of power. “#23: Arrested,” for instance, reproduces, within a controlled environment, the scenario of a physical detention:

Decide who gets arrested and who is the arrestor. The arrestor leads the arrested person around with closed eyes and tells them when they can open their eyes and what they can see. The arrestor can also ask them to bend their knees, turn around, and use their voice to make sounds. Try not to practice this as an aggressive exercise or an exercise about submission. And try to not create a linguistic narrative from the beginning. Just choose to show them normal things that you also react to. Don’t overthink it. It’s important to be close to the centre of the other person – ask them if you may touch their waist, shoulder, and head.17

The nuance in the language in which these instructions are written warrants closer inspection. First, there is the verb, decide. Decide who is who – this is essential to the roleplay since the decision will ultimately lead to one party closing their eyes, activating the element of trust in this exercise and giving the designated arrestor power over the arrested’s sensory experience. In a way, this particular exercise resonates with Do you have time to kill me today? and is an updated version of that roleplay.18

Stine Marie Jacobsen. Do you have time to kill me today?, 2009. Illustrator: Stig Stjernvik

In the case of Group-Think, the role(s) you play are decided collaboratively, not assigned based on preexisting identity traits such as gender presentation or physical ability. Jacobsen’s instructions then explicitly state that “Arrested” is not a study or enactment of dominance, nor is it about constructing a narrative around a hypothetical arrest. These nuances distinguish “Arrested” and the other exercises in the Group-Think handbook from many of Jacobsen’s previous projects, whose goals hinge on a narrative (e.g., the slasher trope and female victim narrative or the horror and paranoia narrative). In this way, Group-Think asks its participants to create protocols from scratch – not based on a movie they know or on power dynamics they are familiar with. This complete reimagining not only frees their critical thinking, but also has them practice making their own rules and thinking about what kinds of interactions they are actually comfortable with.

Another example from the handbook, “#9: Yes/No,” like “Arrested,” mimics a potentially traumatizing and life-threatening experience – in this case, that of a stop and frisk or an encounter with border control:

One person asks the other person as many questions as possible and as quickly as possible without any pauses. The person being asked is not allowed to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ or to nod or shake their head to signal either word. Ask, for example, the person about their day. ‘Did you have breakfast? Do you like coffee?’ Try to ask yes-no questions to test the other person’s ability to resist the urge to only answer with a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’.19

Again, Jacobsen creates not an exact simulation but a training and testing ground for collective intelligence within an environment of trust and safety that teaches young people, to some degree, how to best act when the environment turns hostile.

In a podcast for Manifesta 13, Jacobsen identifies her favorite exercise from the handbook as “#20: (Un)Wrestle”:

Everyone stands in a circle holding hands. One person is appointed “wrestler” and moves outside of the circle so that they can’t see what’s happening inside the circle. Everyone in the circle should now weave their bodies together, stepping over or under each other while still holding hands. When the circle is tightly woven and nobody can move, everyone shouts, “Wrestler, wrestler, come help un-wrestle us.” The wrestler’s task is to bring the group back to its original circular form. Sometimes this succeeds; sometimes it’s impossible. Everyone must keep holding hands during the exercise.20

Stine Marie Jacobsen. Group-Think, Manifesta Biennial 2020. Photo: Stine Marie Jacobsen

To tie a large knot with one’s body, Jacobsen notes, is useful during sit-ins since the goal there is to make oneself difficult to move away. The participants must communicate and cooperate in order to knot themselves together.21 Since the goal is for the handbook to be useful in the real world, the work that Group-Think enacts is meant to be long-term. Regarding the future direction of the project, Jacobsen writes, “Knowing from my other projects Direct Approach and Law Shifters how hard it is to create sustainability without the artists being present all the time, I hope people will use the exercises, which are open source.”22 In this and other projects, Jacobsen strives to enact the writer and curator Tom Holert’s idea of artists as “human search engines” who capture and reformat existing content.23 Or, as Holert puts it: “artists as re-programmers.”24 As I see it, a piece of portable wisdom that comes out of this project is how Jacobsen’s framework can be applied to pedagogy broadly speaking. If we adjust our expectations of the classroom such that we recognize educators as “human search engines,” or as “re-programmers,” and implement a model by which educators learn from artists, then we may find a way for teachers and students to productively co-write the protocols of their “semiprivate room.”25

Group-Think is further scheduled to appear in the first Zabel Biennial in Tirana, Albania, in a Russian translation by the cultural organization “Studio DA!” and as a long-term project with Bétonsalon in Paris, France.

Footnotes

- Ellen Rooney, “A Semiprivate Room,” in differences: a journal of feminist cultural studies 13.1 (2002): 128-156.

- Maggie Nelson, The Art of Cruelty (New York: Norton, 2012): 103.

- Stine Marie Jacobsen, interview with Jenny Wu, personal interview, email, 27 June 2021.

- The notion of “staying with the trouble (of living and dying together on a damaged earth)” comes from feminist scholar Donna Haraway’s theory that building more livable futures starts with acknowledging the interconnectedness of lifeforms and eschewing ways of thinking that privilege the individual as autonomous or self-generating. See: Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

- Stine Marie Jacobsen, “Being part of Manifesta with Stine Marie Jacobsen,” Manifesta Biennial, date of access: 29 July 2021, https://tinyurl.com/5m5jvkh8.

- Stine Marie Jacobsen, Group-Think (Berlin: Broken Dimanche Press, 2020): 41.

- Augusto Boal, Games for Actors and Non-Actors, trans. Adrian Jackson (London: Routledge, 1992): 71.

- Stine Marie Jacobsen, Group-Think (Berlin: Broken Dimanche Press, 2020): 41.

- In Direct Approach, Jacobsen asks people to retell from memory a violent film scene they have watched and to choose whether they would play victim, perpetrator or bystander and explain why. Sometimes the artist films the participants in a retake of the film scene, but most of the time it is a project free of imagery. The conversation is the core of this project. Jacobsen does not stress the production of any image and instead emphasizes the iconoclastic element of these exercises.

- Through her project Law Shifters (2016-), Jacobsen, together with lawyers, organizes courtroom roleplays and invites people to rejudge real court cases and write their own laws.

- Charles Hadji, “Débat: Le bac a-t-il encore un avenir?” in The Conversation, 24 June 2021, date of access: 29 July 2021, https://theconversation.com/debat-le-bac-a-t-il-encore-un-avenir-163323.

- “New Report: 6 in 10 Countries Now Seriously Repressing Civic Freedoms,” Civicus: Monitor, date of access 29 July 2021, https://tinyurl.com/8b9v6h8p.

- “Article 431-3,” Code pénal, date of access: 29 July 2021, www.codes-et-lois.fr/code-penal/article-431-3.

- Stine Marie Jacobsen, interview with Jenny Wu, personal interview, email, 27 June 2021.

- Ibid.

- Fred Eugene Leonard, A Guide to the History of Physical Education (Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1923): 90.

- Stine Marie Jacobsen, Group-Think (Berlin: Broken Dimanche Press, 2020): 45.

- As part of the project, Jacobsen appropriated a Danish reader’s digest magazine to write a kitschy crime story and illustrate Do you have time to kill me today? (2007-09).

- Ibid., 25.

- Ibid., 42.

- Stine Marie Jacobsen, “Being part of Manifesta with Stine Marie Jacobsen,” Manifesta Biennial, date of access: 29 July 2021, https://tinyurl.com/5m5jvkh8.

- Stine Marie Jacobsen, interview with Jenny Wu, personal interview, email, 27 June 2021.

- Tom Holert, Knowledge Beside Itself: Contemporary Art’s Epistemic Politics (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2020).

- Ibid.

- Ellen Rooney, “A Semiprivate Room,” in differences: a journal of feminist cultural studies 13.1 (2002): 128-156.

Jenny Wu is a writer and an art historian. She received her bachelor's degree from Emory University and an MFA in fiction writing from Washington University in St. Louis. She served as the writing program’s Senior Fiction Fellow before receiving a second master's in art history, specializing in global contemporary art and performance. She has worked for organizations such as The Luminary and the Pulitzer Arts Foundation and contributed to the Universities Art Association of Canada (UAAC) conference, London Centre for Interdisciplinary Research, Southeast College Art Conference, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and Tin House Summer Workshop. Her short stories, literary reviews, scholarship, and art criticism have received generous support from Rona Jaffe Foundation, George Kaiser Family Foundation, Louis B. Sudler Prize in the Arts, and Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry and appear in publications such as Asymptote, BOMB, Denver Quarterly, Harp & Altar, Refract, The Literary Review, and Los Angeles Review of Books. A recipient of the 2021-23 Tulsa Artist Fellowship, she is currently based in Tulsa, Oklahoma.