UMBILIC

Natasha Thembiso Ruwona

November 2021

Trigger warnings: mentions of violence, death, loss, racism

What can we learn from water? Fluidity, impermanence, ease of movement, care, methods to listen, tenderness. UMBILIC is an offering – forever incomplete. This work began in 2020, incidentally designated Scotland’s Year of Coasts and Waters (which has been continued into 2021). I hope for UMBILIC to become a location in itself; an entry point into uncovering different (hi)stories that can help to situate our liquid selves. I hope that we look to water to guide us, provide answers, and inspire questions.

To all the wombs that lay upon the ocean floor.

To all the wombs that never made it to the shore.

UMBILIC offers an expansion of the current discourse on Hydrofeminism through a mapping of my research into water, in line with a Black Feminist Geographical framework. Scholar Katherine McKittrick first put forth the latter as an exploration of the relationship between Black women and geography,1 visible through architecture, movement and migration. Hydrofeminism, a concept derived from Astrida Neimanis,2 speaks to the relationship that exists between humans and water, through our beginnings in amniotic fluid, journeys across or through the ocean, and to our futures impacted by the rising sea levels, as a result of climate change.

Through uncovering a more inclusive understanding of Hydrofeminism in relation to Blackness, it broadens the potential of both concepts and lends itself to the study of Black Feminist Geography by creating a focused discourse on water within the field, furthering the work already achieved within Black Atlantic study.3 The Black Atlantic, a term first used by Paul Gilroy in 1993, has been developed into the study of African identities and cultures as they have formed across the Atlantic Ocean. The continent and the Diaspora find their meeting point within the Atlantic Ocean to symbolise the Old and New worlds that were created by the Translatlantic slave trade. This work forms only one part of what I am calling Scottish Black Atlanticism, an exploration into the impact of Scotland’s contribution in the formulation of the Black Atlantic.

BEGINNINGS.

Location: Amniotic Sac, the human body.

A border of protective liquid shapes the fetus within the womb; beginning a series of exchanges between Bearer and baby.

{Release of said liquid}

Our bodies become containers to hold the water within us (60-90%). Replenish. 6-8 glasses a day.

Can humans breathe underwater?4

Earth may have birthed into its own clay womb,5 with remnants that can be found at the bottom of the ocean.

Can humans breathe underwater? 70% of the world’s surface.

Katherine McKittrick and Clyde Woods describe how the ocean,

“prompts a geographic narrative that may not be readily visible on maps. This tension between mapped and the unknown reconfigures knowledge, suggesting that places, experiences, histories, and people that no one knows do exist.”6

I believe that this tension described allows those of us who are left outside of conventional narratives to investigate unknown and underexplored sites as our own territory.

Plato created The Atlantis, a fictional underwater world that claims to play host to a utopian society full of human advancement situated within the Atlantic Ocean. This concept was evolved further into a Black Atlantis, informed by the mythology and music of Detroit electro duo Drexicya.

Taking its name from its creators, the underwater world of Drexciya inhabits the ancestors of the enslaved. The middle passage formed part of the triangular trade during slavery where Africans were forcibly taken onto boats to the Americas. Drexciya’s theory is that of the pregnant slaves who were thrown overboard or jumped during the middle passage, then had their babies in the ocean who adapted to breathing underwater, creating an advanced underwater civilisation.

Drexciya’s fictional narrative is inspired by the real life Zong massacre that happened in 1781, where more than 130 slaves from the British ship the Zong were thrown overboard in a fraudulent insurance claim made for bodies-turned-cargo.

your child, like currency.

tears

wept,

tears

swept,

away

lost, but yet

found in deep depths.

became a part of the ocean,

so often feared.

THE HOLD

Location: Floating/sinking with(in) the Atlantic Ocean and with(in) the pages of my books, words, womb.

The Middle Passage as Birth Canal7 takes

The factory of the Belly

As its laborious space

Womb.

Birthing Borning Producing

Womb.

Moon; pushing and pulling

Holding (on)

Held

Sunken

Lost

Is the Belly of the World.8

I, too, become

The principal point of passage between the human and the non human world.9

I, too, become a memory of the future.

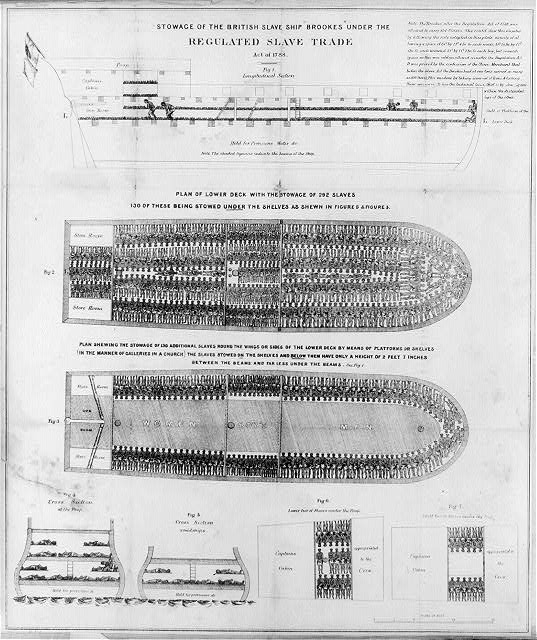

“Stowage of the British Slave Ship ‘Brookes’ under the Regulated Slave Trade, Act of 1788.” Courtesy of US Library of Congress.

The Ship10 is reimagined by Christina Sharpe, and its Hold becomes a metaphor for its Belly – its very own womb that births Blackness. The Hold evolves into; the prison, the institution, architectural repetition.11

Plan of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon prison, drawn by Willey Reveley in 1791. Source: “Panopticon,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panopticon.

Water is the metaphor for locating the fluidity of Blackness and Queerness in Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley’s text,12 as both identities intertwine themselves together. Tinsley takes the slave ship Hold as her setting to imagine Black bodies as being queer in the sense of

“connecting in ways that commodified flesh was never supposed to, loving your own kind when your kind was supposed to cease to exist, forging interpersonal connections that counteract imperial desires for Africans.”

desire; a touch, gentle, soft, rough, needily, held, let go, lust, lost. bodies of erosion, landscapes – to the water we return.

In her book Ezili’s Mirrors: Imagining Queer Black Identities (2018), Tinsley speaks of the many forms that the Caribbean water spirit Ezili has taken across performance, art and literature. How do we (dis)appear, reappear, re/locate ourselves? Where are our mirrors and who do they reflect back? Fluid spirited beings remind us that in the water we can be/come anything at all, our Black Queer tears / fears masked.

What could anyone do with this rising water but emulate the amphibians?13 Fishy existences14 compliment and counteract human binaries; genderless / genderfull, gills, fins, tails – in the water we can be/come anything at all.

The Atlantic ocean as an instrument for connecting lost bodies, lost histories, forced or chosen migration, the transportation of goods and bodies, bodies that were and are defined as being goods, water spirits who await evocation.

AN ACT OF UNION

Illusion, presence, memory and dream.

The Leith Port in Edinburgh played a vital part in Scotland’s mass tobacco trade, beginning in the early 17th century with the first recorded ship, the Job, returning to Leith from Virginia in March 1667. There were at least two voyages from Leith that are said to have taken place on vessels transporting the enslaved in the 18th century,15 which could possibly include a documented ship that left Leith for the Gambia, reaching Barbados in 1784.

‘Sugar Houses’ in Leith helped to refine transported sugar, with at least 4 existing within the city.16 Import, export, import, export. Scots built the tools, sold the goods, sale and set sail.

In 1766, the River Clyde in Glasgow was carved out for the expansion of trade across the Atlantic Ocean so that larger ships could be built and sailed through and across all of the UK’s main trading ports and docks.17 The architecture itself of the River Clyde participates in the act of hydro-colonialism;18 the role of human maritime activity in the colonisation of the ocean.

Shallow dreams find depth in waters developed for trade. 1741 saw 8 million pounds of tobacco being imported into the Clyde,19 with the deepening of the river only assisting in the processes of the transatlantic trade. The Clyde as a memory, a myth of industrial influence, the imagination of nationalism embedded and informed by what once was.20

Early presences of Black people in Scotland can be heavily felt in Leith, with reasons that can be attributed to arrivals, birth, baptism, education, work at sea, and departures. Historical accounts of these presences in Scotland speak of two African women who were captured from a Portuguese ship, and arrived via Leith in 1506, presented as gifts to King James IV. 21

AQUATIC / EXOTIC / AQUATIC / EXOTIC.

A notice for a runaway in the Edinburgh Evening Courant in 1773 details a Black man – a sailor, may have been located in Leith searching for work and freedom.

A r c h i t e c t u r a l r e p e t i t i o n

Water’s movement is constantly in flux yet, river’s are said to provide a sense of locatedness. I wonder what this word means and if it is possible while being Black in Scotland. 20th century Scotland saw many African Sailors residing by Scottish waters, including Manuel Abrew, who alongside his brother Charlie were Scotland’s first African boxers. Born and bred in Leith, Manuel gave up on boxing due to racism and became a sailor.

A r c h i t e c t u r a l r e p e t i t i o n

The Broomielaw race riots of 1919 were incited after rumours spread about African sailors who had travelled to the Clyde for work and had agreed to be paid lower wages, stealing the jobs of their white local counterparts. The riot broke out and Black sailors found themselves being chased by the white sailors, as well as members of the public who then attacked them, even as they attempted to seek safety in the Broomielaw sailors’ accommodation. The crowd grew in its hundreds and got extremely violent – with the police arriving and charging the African sailors, letting the white rioters remain free.22

Time travelling particles pass through estuaries. How many times has the water from the Atlantic Ocean met the River Clyde, or Leith Port?

A r c h i t e c t u r a l r e p e t i t i o n

The British Empire as a memory, a myth of industrial influence, the imagination of nationalism embedded and informed by what once was.

(HE) SELLS SEA SHELLS.

Location: Dunbar, East Lothian, Scotland.

Object found: Cowrie shell; Encasing is smooth yet marked with ridges. The shell swallows its secrets behind its teeth. Its size demands for a conscious handling.

Cowrie shells: a form of currency once used amongst people within the Global South. During the slave trade, Europeans took advantage of their high value as held by Africans and began trading cowries in exchange for slaves. A third to a quarter of the six million plus Africans taken to America were sold in exchange for shells. THE SHELL IS RECAST INTO A SYMBOL FOR HUMAN LIFE AS IT BECAME A FORM OF COMMERCE. “One pound of cowries in exchange for every thirteen pounds of human flesh.”23 This repurposing of the cowrie shell, as with its resemblance to a vagina mirrors the transactional and anatomical value of Black bodies as created by Europeans.

And how might these shells have found themselves on the beaches of Scottish Coasts? Are there ghosts of the sea longing to communicate truths, to drift the sunken evils of Scotland’s very own Black history to the surface.

Bodies of water; floating, swimming, surviving, sinking. When was breathing forever an option that we could afford?

We sit within a bereavement of being able to breathe with ease.

The apocalypse has already happened – welcome to the afterlife. As ice becomes a memory,24 must we begin carving waters to hold rising sea levels?

magnetic moon shaping, instructing tide

under the surface we reside.

and so while we wait,

for our lungs to adapt

we bite tongues,

choke on dry landThe sea as the repository for all the crimes of empire.25 The Hold of History; once held, placed, forgotten, sunken, lost. When was breathing forever an option that we could afford?

SCORPIO, A WATER SIGN.

VESSEL OF THE PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE.

DRAWN TO THE (IM)POSSIBILITIES OF THE OCEAN.

Location: somewhere in the stars.

I have fallen deeper into waters and my dreams

/ dreams of water

Whatever that may mean.

So, I must, too, become a memory of the future.

UMBILIC CREDITS

Featuring (Player) Tanatsei Gambura

Sound by Clara Hancock

Funded by HUBCAP Gallery and Civic Square Dream Fund

Footnotes

- Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and The Cartographies Of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006).

- Astrida Neimanis, Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017).

- Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993).

- Drexciya, The Quest (Detroit: Submerge, 1997).

- Tudor Raiciu, “Researchers Discover the ‘Primordial Womb,’” Softpedia News, 29 Nov. 2005, https://tinyurl.com/y8bs7bcp.

- Katherine McKittrick and Clyde Woods, “No One Knows the Mysteries at the Bottom of the Ocean,” Black Geographies and the Politics of Place (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2007).

- Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

- Saidiya Hartman, “The Belly of the World: A Note on Black Women’s Labors,” in Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society, vol. 18, no. 1 (2016): 166-173.

- Hortense J. Spillers, Interstices in Black, White and In Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

- “Stowage of the British Slave Ship ‘Brookes’ under the Regulated Slave Trade, Act of 1788,” The Abolition Seminar, 25 Nov. 2013, https://tinyurl.com/zdjhzmzh.

- Sharpe, In the Wake, 2016.

- Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley, “BLACK ATLANTIC, QUEER ATLANTIC: Queer Imaginings of the Middle Passage,” in GLQ, vol. 14, no. 2-3 (2008): 191–215.

- Alexis Pauline Gumbs, M Archive: After the End of the World (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018).

- Neimanis, Bodies of Water, 2017.

- Mark Duffill, “The Africa trade from the ports of Scotland, 1706–66,” in Slavery & Abolition: A Journal of Slave & Post-Slave Studies, 3 (2004): 102-122.

- City of Edinburgh Council, Museum of Edinburgh, “It Didn’t Happen Here! Edinburgh’s Links in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade,” Antislavery Usable Past, 2007, https://tinyurl.com/jf7zeana.

- “Tobacco Lords,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, https://tinyurl.com/56cn6cxj.

- Isabel Hofmeyr, “Provisional Notes on Hydrocolonialism,” in English Language Notes, vol. 57, no. 1 (2019): 11-20.

- W. Iain Stevenson, “Some aspects of the geography of the Clyde tobacco trade in the eighteenth century,” in Scottish Geographical Magazine, vol. 89, no. 1 (1973): 19-35.

- Minty Donald, “The Urban River and Site-specific Performance,” in Contemporary Theatre Review, vol. 22, no. 2 (2012): 213-223.

- June Evans, “African/Caribbeans in Scotland: A socio-geographical study,” PhD dissertation, Edinburgh Research Archive (1995), https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/7187.

- Craig Williams, “Remembering the ‘Broomielaw Race Riot’ of 1919 – one of Glasgow’s ugliest days,” GlasgowLive, 22 Jan. 2019, https://tinyurl.com/jactn2bn; Tomiwa Folorunso, “Time Travels, Episode 2, A Riot Broke Out Down by The Clyde in 1919,” BBC Radio Scotland, 2 Oct. 2018, https://tinyurl.com/4dkkvdtj.

- Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (New York: Macmillan, 2008).

- Sonja Boon, Lesley Butler and Daze Jefferies, Autoethnography and Feminist Theory at the Water’s Edge: Unsettled Islands (London: Palgrave, 2018).

- Anuradha Vikram, “Underneath the Black Atlantic: Race and Capital in John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea,” X-TRA, vol. 21, no. 3 (2019), https://www.x-traonline.org/article/underneath-the-black-atlantic-race-and-capital-in-john-akomfrahs-vertigo-sea.

Natasha Thembiso Ruwona is a Scottish-Zimbabwean artist, researcher and film programmer based in Glasgow. They are interested in Afrofuturist storytelling through the poetics of the landscape, working across various media including; digital performance, film, and writing. Their current project “Black Geographies, Ecologies and Spatial Practice” is an exploration of space, place and the climate as related to Black identities and histories.