Vessel: A Meridian Practice

Viviana Checchia and Anna Santomauro

November 2022

Vessel is a nomadic curatorial organization and agency invested in supporting artistic and curatorial practices that are situated, responsive, and research-led. Driven by a biographical and epistemological belonging to the South – the Southern Europe and Mediterranean regions in particular – we are interested in how the social and ecological imagination can be enhanced in order to critically engage with the sets of conditions and infrastructures that sustain contemporary cultural practices.

Vessel has devoted great attention to the definition and development of socially engaged art practice and contributed internationally through the application of socially engaged tools and methods in contemporary curatorial practice, always from a perspective “other” than the mainstream. Vessel’s practice – embedded in an ongoing act of hosting and being hosted – manifests itself through public programming, commissioning, and writing. In the last ten years Vessel has participated and contributed to shaping an understanding of curatorial practice epistemologically connected to a locale (or locality), though not by default based within it. Vessel’s core curatorial team includes Viviana Checchia, Nicoletta Daldanise, and Anna Santomauro.

The following text is an edited transcript of a lecture held on July 8, 2021 by Viviana Checchia and Anna Santomauro, organized by the Innovative Training Network FEINART (The Future of European Independent Art Spaces in a Period of Socially Engaged Art) jointly led by the University of Wolverhampton, Zeppelin University, University of Iceland, and University of Edinburgh. In the context of MARCH’s ongoing feature Publishing As Protocol, this presentation outlines Vessel’s collective, socially engaged curatorial practice: situated but nomadic, responsive but not embedded, instituting but not institutionalized.

We would like to start by clarifying our use of, and position on, the term “socially engaged.” By socially engaged, we refer to practices whose catalyst is society; their point of departure is a social issue. They do not have to be socially engaged in the sense of recreating a sociable situation through the participation of human beings (or animals or plants). In this sense, Vessel’s social engagement is expressed towards society, its culture and at times its members, too, of course, though not always directly. In this respect, we would also like to clarify that Vessel, as a curatorial organization, does not commission socially engaged art projects as a default approach. Instead, the ethos of socially engaged art informs our way of working: therefore, our practice embodies social engagement.

The references we will use are mainly, though not exclusively, from the South: the epistemology that we are rooted in – even within our nomadic profile. The structure of this text follows the preface of the book by social scientist Franco Cassano titled Il pensiero meridiano, or Southern Thought.1 For the title of this lecture, we decided to use the word “Meridian” rather than “Southern,” which is how the title of the book is officially translated to English.2 Meridian hints at the conjunction of space and time, which seemed appropriate for this occasion.

The first edition of Il pensiero meridiano was published in 1996. After a wide distribution and various poignant critiques of the book, Cassano decided to write an exhaustive preface to address some of the critiques as well as reflections he had made between 1996 and 2004. In the 2005 edition, the preface is divided into four sections: Autonomy, Slowness, Mediterranean, and Measure. These four focuses guide our presentation and function as lenses through which to see the practice Vessel has developed during the last ten years. The text will not follow a linear, chronological timeline. Instead, we will refer to specific projects that Vessel has developed on the basis of these four lenses. The objective we have is to share a theoretical understanding of our socially engaged curatorial practice and to explore how that can inform and guide alternative approaches.

AUTONOMY

The notion of autonomy is crucial in Cassano’s understanding of “Southern Thought.” There are three ways in which he talks about autonomy that resonate with what has so far driven Vessel’s work.

- The autonomy of the South in opposition to the universalism of the dominant culture, which he identifies as belonging to the North – be it the Global North or Northern Italy.

- The autonomy of representation, or the South’s rebellion to its representation, which in the words of Cassano is “torn between a tourism heaven and a corruption hell.”

- The autonomy of the route toward emancipation for Southern Italy, which in Cassano’s view should exceed the national horizon and re-situate itself within a South-South network of relationships.

Vessel’s work has mainly been concentrated in the region of Puglia, in the southeast of the country. Puglia is one of the regions historically at the core of the so-called Questione Meridionale (the Southern Question), an expression that broadly identifies the economic, political, and cultural gap between Northern and Southern Italy in the aftermath of the country’s unification in the nineteenth century. In the main historical accounts of the Southern Question, this gap hints at the arretratezza – backwardness – of the South and at the need to level North and South on the premise that the latter should catch up with the former. This temporal hiatus implies that the South is in a structural, ongoing position of delay or lateness and of impossible and passive imitation of the North. Cassano seeks to break away from this view, repositioning Southern Italy (and the South in general) as the subject and not the object of its own thought.

Puglia’s recent social, cultural, and economic history can be considered as emblematic of this dynamic. Historically, the economy of the region has mostly been based on agriculture and services, while the industrial sector is mainly based on small- and medium-sized firms. In the last fifty years, two highly capital-intensive, large-scale plants – Ilva (steelmaking) and Eni (petrochemicals) – have deeply changed the socioeconomic landscape of parts of the region, providing salaried jobs within small port cities and introducing modes of organization closer to the urban working class rather than the traditional fishing communities. Initially owned by the state company Italsider, in the 1960s Ilva in Taranto combined its economic strategy with a social and cultural one – for instance, through the Rivista Italsider, the company’s magazine, which commissioned artists to create covers and illustrations around the future of the city.

In 2012, Ilva was investigated for environmental crimes and pollution. While plants with similar environmental impacts have been dismantled in different parts of Italy – one of them being Porto Marghera near Venice – Ilva is still functioning and still polluting, forcing parts of the city to go into lockdown when the levels of dioxin in the air are too high.

Since 2008, tourism has been on top of the regional council’s agenda, presented as inextricably linked to the promotion of both traditional and contemporary culture. This led to the founding of large-scale institutions like the Apulia Film Commission, which invited international cinema productions to shoot their new productions in Puglia, benefiting from the Mediterranean light and landscapes. In a similar vein, tourists were invited to leave behind their stressful lives and fall in love with Puglia through large-scale campaigns that sought to rebrand the region as an idyllic and authentic place to live the good life. In the same years, architect David Chipperfield was commissioned to renovate Teatro Margherita, a theater in Bari, and turn it into a contemporary art museum (although the museum never opened). Over the course of around eight years, Puglia started to appear as the anomaly of the South, a fertile territory for innovative ideas and massive tourism, leaving behind the burden of the perception that the Southern Question had imposed on the region.

Also in 2008, the regional government started to invest a large part of the European Union’s funding for regional development in order to promote youth policies and culture. This has been one of the strategies that the regional council has adopted to try to stop the traditional move of young people (students and workers) to the North of Italy or the rest of Europe, in search of better education and job opportunities. Since then, through EU funding, hundreds of creative projects in different disciplines have been supported with a grant of 25,000 euros: associations, cooperatives, and companies have mushroomed throughout the region, transforming Puglia into a laboratory for social innovation in a very short time. This created a situation where those that chose to establish themselves as not-for-profit organizations could not access further regional funding and support, whereas those that opted for a for-profit status were able to apply for further grants.

We founded Vessel in 2011, in the midst of the so-called Primavera Pugliese (Puglia Spring) and in the context of this regional youth program. From the outset, our main challenge was to operate within a region with a fragile set of infrastructures that at the same time was undergoing a process of acceleration and self-exoticization. We decided to withdraw from the way the region was representing itself by avoiding the then dominant logic of the festival, the big event, and the traditional exhibition, instead introducing forms of artistic and curatorial production mostly based on conversation, dialogue, experience, and process without an end product. Rather than focusing on a tangible outcome, since its inception, Vessel has performed a process of dynamic discussion that could be considered as a space of resistance from the cultural and touristic commodification of the region.

We moved away from the format of the exhibition partially to escape the choice between either displaying international artists – brave, cutting-edge political works that we might have encountered in biennials or exhibitions abroad – or presenting the work of artists from the region to give them national and international visibility. Instead, we opted to create a porous infrastructure: an organization that could be open, flexible, and even prone to failure at times – that could facilitate the encounter of international artistic and curatorial practices with local cultural and art workers, self-organized collectives, and practitioners from different fields. The specificity of the region provided a fertile terrain for these encounters and for different types of artistic and curatorial research.

This mode of instituting provided us with a space of curatorial autonomy – both from the global art system expecting peripheries to mirror what was happening in the major capitals and from the regional government agenda that had a sudden desire for contemporaneity. Our work has taken place in urban settings – like the capital city of the region, Bari – as well as in rural areas.

In 2015, we initiated Terra Piatta (Flat Land), a program of art-led inquiries that over three years brought together artists engaging with themes of ecology, land use, and agriculture with farmers, workers, activists, and architects based in the region. We focused on a specific area called Capitanata in the northernmost part of Puglia, the so-called “granary of Italy,” where agriculture is the main activity and the few industries present are mostly devoted to food processing. Almost every peeled tomato in Europe comes from this area. Every year, two million tons of tomatoes are produced, but the revenues for local farmers are extremely low. The workforce involved in the harvesting of tomatoes is mainly composed of undocumented migrants.3

During the fascist regime, the area was deeply affected by the agrarian reform that instituted a plan of reorganization and reclamation of the land. Marshlands and wetland were made arable and Mussolini’s regime introduced a territorial and social planning based on the construction of borgate (new villages) and poderi (farmhouses). Many former soldiers and peasants settled in these places, inhabiting fascist modernist architecture. In each borgata, the territory was equally portioned to include a school, church, market, and public offices, in order to avoid the daily commute to cities. The system failed soon after the collapse of fascism in Italy. The local Apulian people did not like the isolation that the borgate fostered and missed the village interaction, which resulted in the abandonment of the podere and a return to the city during the “economic boom” that followed.

Through the years, these areas were forgotten or ignored as part of the disavowal of those dark times in Italian history. Yet, many of these areas have attained considerable autonomy, having to solve questions of security, justice, education, and other services in relative isolation. Others, increasingly in ruins, are often inhabited by seasonal workers. In the context of Terra Piatta, Vessel developed:

- A residency with Fernando Garcìa Dory in collaboration with the architecture collective XScape, where the artists met local farmers, cheesemakers, artists, educators, and councilmembers to map out the desires for the future of the borgate and to seek to define what a network of these small villages could become.

- Tre Titoli, a film by artist Nico Angiuli, scripted and performed with seasonal workers – mainly undocumented laborers from Ghana working in the harvest of tomatoes. The film brought together migrant and Italian workers to collectively explore the legacy of Giuseppe Di Vittorio, one of the founders of the Italian unions who, as a young boy, was an exploited peasant in this same area.

- The 2016 International Curatorial Workshop led by Nuno Sacramento and Sanne Oorthuizen, where we spent four days in a local farmhouse exploring social practices and deep mapping within a non-urban context with a group of fifteen curators.

- A series of artist-led workshops titled Rural in Action that engaged local communities in artistic and civic practices exploring themes of ecology and the periphery. The title of the program draws inspiration from Culture in Action, the iconic project curated by Mary Jane Jacob in Chicago in the early 1990s, where artists were brought into dialogue with communities in different parts of the city.

SLOWNESS

Cassano’s Southern Thought and Vessel have an issue in common: the invitation to “slowness” is easily misunderstood. Though the majority of people encountering this approach are fascinated and interested in its applications, a minority interprets slowness as a way to somehow idealize the South and give it attributes it never really had. What most interested Vessel was to disconnect the idea of speed from the idea of progress, the idea that acceleration would forever go hand-in-hand with human development. In all these years of practice, Vessel has experienced a very slow pace made of brief and sometimes long disappearances. Within this ethic, Vessel has also embraced an everyday-based structure rather than an event-driven structure. This has meant that we have privileged the day-by-day running of Vessel and its evolving life rather than living in the mindset of preparation for the next “spectacular” thing.

Vessel 2015 International Curatorial Workshop (ICW) in Bari, Italy. Photo courtesy of Tirdad Zolghadr.

Since 2011, Vessel has been running the International Curatorial Workshop (ICW). Conceived as an attempt to rethink educational models and to test what a self-organized curatorial para-institution can do in a peripheral context, ICW consists of a four-day gathering that brings together groups of international curators willing to explore different questions such as curating as a situated practice, the legacy of institutional critique in contemporary institutional and non-institutional practices, curatorial approaches to socially engaged art, self-education, and hospitality as a site for knowledge production. The various editions of ICW were created in collaboration with the University of Bari, European Cultural Foundation, Roberto Cimetta, Van Abbemuseum, Monash University, and Konstfack. During those days, we would take it slow, give space to dialogue, and spend around four or five hours per day making food, eating, drinking, and conversing.

Vessel 2017 International Curatorial Workshop in Bari, Italy. Photo courtesy of the authors.

In our so-called acceleration society, dialogue and democratic sharing are considered a waste of time. Vessel was and is conscious that conviviality (cum – vivere as Cassano calls it) is as valuable and important as moments of presentations and workshops. Most of the relevant and long-term partnerships Vessel witnessed and developed were in part germinated during a lunch or dinner. (Gentle reminder: we are talking about 2011 when attention toward care and questions of hospitality was perhaps not as present within the contemporary art discourse as it is now.) Vessel has existed in a multiplicity of times and we have tried to preserve the long-term as an important value in the establishment of meaningful engagements.

Another concept that can help us express Vessel’s approach to slowness and decelerated durationality is a concept from the Global South termed nongkrong. As independent artist and researcher Sonja Dahl explains in her 2016 article, “Nongkrong and Non-Productive Time in Yogyakarta’s Contemporary Arts,” at first glance nongkrong just means “hanging out.”4 This literal translation does not do justice, however, to the deep and complex societal and intellectual value of this activity. In urban settings within Indonesia, this slow and fluid form of dialogical exchange has been a way to learn from people’s differences, explore in depth the meaning of life, and challenge worldviews in a collective way.

Compared with modes of Western dialogical sharing and conversation, nongkrong can appear extremely unproductive, unfocused, unstructured, and therefore useless – at least according to an accelerated capitalist logic. The reality is that this mode of interaction is highly conducive to collaborative work: people find time to express themselves; they do not feel the pressure of speeding to a conclusion or a final outcome and are therefore not moved by competition but by a sense of solidarity. Ruangrupa, for example, tried to incorporate this principle within their modus operandi: a first step toward emulating the durational and cooperative exchange and iterated meaning-making of nongkrong. Rather than deploy a pre-tested, recognizable production mode or exhibitionary form, they have opted for a non-mainstream form of discourse production embedded within Indonesian society. This corresponds to the ways in which Vessel has tried to operate, embedded in local epistemologies.

MEDITERRANEAN

The Mediterranean plays a key role in the definition of Cassano’s “Southern Thought,” and the author sees it as a site of contamination, hybridization, and exchange. This is a matter of great interest for Vessel, which we have developed particularly through Radio Materiality and Istituto per l’Immaginazione del Mediterraneo (The Institute for the Imagination of the Mediterranean). Both projects invited artists and curators to consider “being situated” in the Mediterranean region as a starting point to develop a series of art-led inquiries.

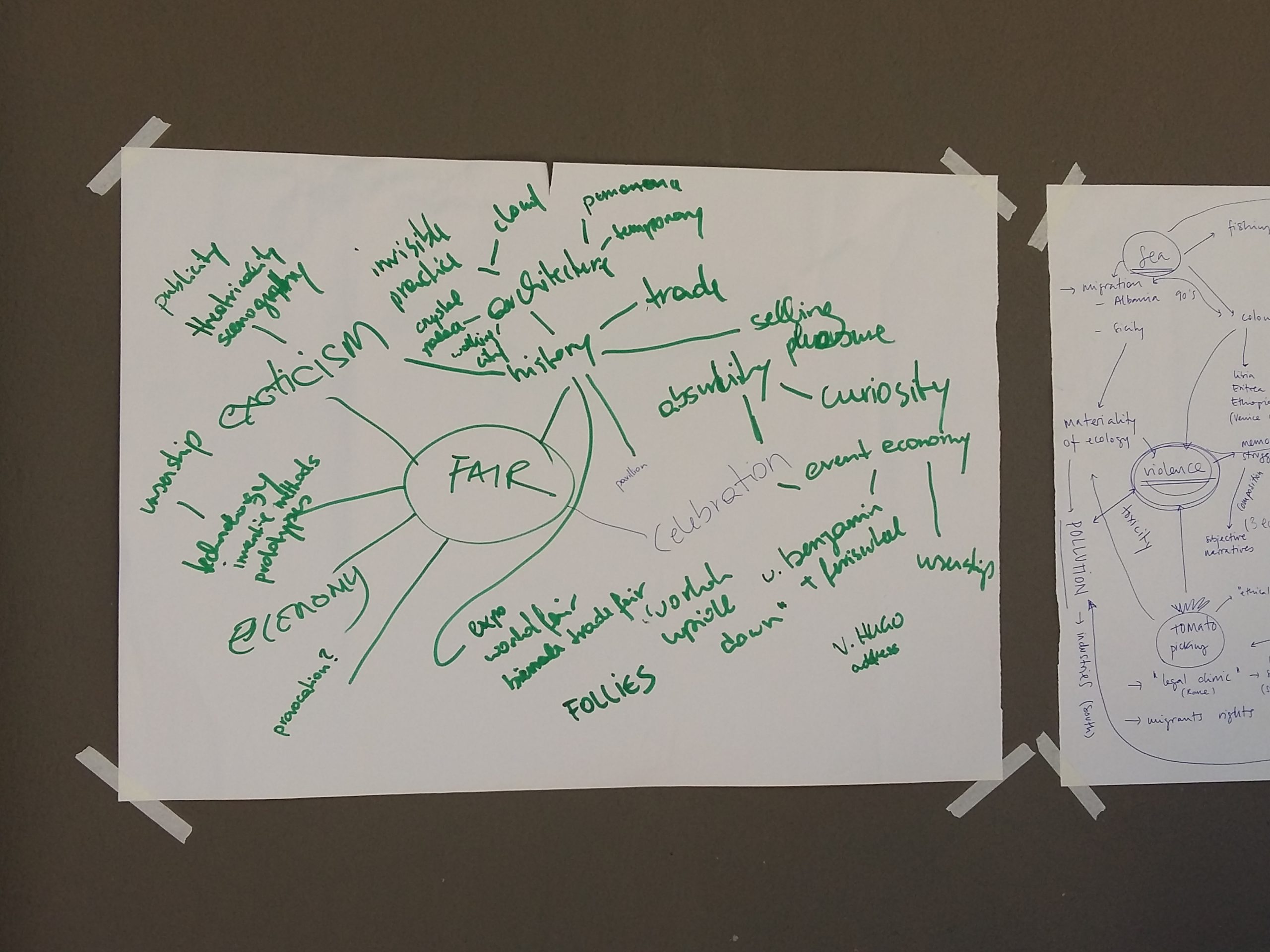

Vessel Mediterranean Perspective Workshop. Courtesy of the authors.

Radio Materiality invited artists to reflect on the notion of transmission and on ways of performing it through a series of residencies. Each artistic intervention was the result of a deep dialogue between the curators, the artists themselves, and local associations, activists, and practitioners: we operated as curators and as co-producers of each action, accompanying the artists in the accumulation and processing of knowledge about the territory, highlighting specific issues they could address, and facilitating the creation of a relational context to operate with.

Bisan Abu Eisheh investigated the state of confinement around the life of a segment of political refugees in the region and focused on the role that art and creativity play in situations of segregation and imprisonment. This interest informs most of his artistic research and relates to the experience of his father’s incarceration in an Israeli prison during the 1980s. While in prison, the artist’s father illegally built a radio device in order for news and information to enter the prison so that inmates would not lose a connection with the outside world. The artist worked with migrants whose refugee status was in the process of being approved: some of them were occupying an abandoned school in Bari, the capital city of the region. The artist gave a series of workshops about how to build radio devices and how to create radio programs to broadcast to the surrounding areas.

Elena Cologni performed a series of conversations between herself and a group of mothers based in Bari to share the emotional and psychogeographical condition of motherhood in the city. These meetings instigated conversations on the concept of trust and on the social and urban dimension that being mother implies – especially in a city like Bari, which suffers from a complete lack of support and infrastructure for families, and where women often perform duties of care that social welfare should provide.

Also in Bari, Jaume Ferrete developed an iteration of his project called Voz Rara, an attempt to hybridize situated knowledges and practices about local feminist legacies with ongoing research on the uses, functions, and accidents of the voice. Through an exploration of the workshop format, the artist introduced the topic of the voice within different forms of activism and engagement related to feminist and LGBTQ+ struggles by defining a series of connections between the voice and power structures and between the voice and the public sphere in the Southern Italian context.

Leone Contini investigated the notion of reciprocity between Puglia and Albania by building a homemade antenna in order to capture the Albanian TV signal from the old harbor of Bari. At the beginning of the 1990s, many Albanian citizens migrated to Italy via the coasts of Puglia. They were well-acquainted with Italian culture and the language – they had watched Italian television, some by building illegal homemade antennas that would allow them to capture foreign broadcasts. The artist had previously conducted research on how to build a homemade antenna during a residency at Tirana Art Lab, and in Bari he tried to create a similar device with cans, a pan, and pieces of wood. After many attempts, we managed to watch the Albanian news for almost half an hour. The process spontaneously involved students, migrants, retired people, and anybody who had expertise to share.

Vessel Pavilion for Istituto per l’Immaginazione del Mediterraneo (IIM), 2018. Photo courtesy of the authors.

Initiated in 2018, Istituto per l’Immaginazione del Mediterraneo (IIM) looked at artists’ modes of organization in the Mediterranean region. Artists whose practices adopt cooperative methodologies and whose research manifests itself through social and political processes were brought in dialogue with regional groups and constituencies whose multiple forms of engagement operate locally and trans-locally.

Luigi Coppola in-residence with Vessel.

In the context of the IIM, Luigi Coppola developed a segment of his ongoing project Evolutionary Populations, a commoning practice inspired by geneticist Salvatore Ceccarelli. The practice of Evolutionary Populations involves sowing mixtures containing hundreds of different varieties of seeds that come from different geographic areas of the world, and leaving it to the earth to choose the varieties to grow depending on climatic and soil conditions. Through an ongoing dialogue with local organizations and experts who work on the care of common goods and sustainable material conditions in agriculture, the artist has created a series of gardens in Bari inspired by his artistic research.

MEASURE

Measure here is to be understood through Cassano as the capacity and potentiality of cultural cohabitation – without hegemony or subjugation of any culture involved. Cassano encourages us to celebrate the fact that all cultures have something precious within them. And to extend this, we see measure as a description of and an invitation to a condition of balance. Within the book Southern Thought, “measure” is offered as a balanced point between the land and sea: the land as the space of identity and social connections, and the sea as the departure point, the adventure, the play of individual freedom. For Vessel, our “measure” consists in the relationship between local and global, settled and nomadic. We don’t want to dominate the local scene, we want to find a way in which local and international experiences can live together in balance.

The Nigerian writer and poet Wole Soyinka compares Western culture to a train that proceeds to seek and gather the “new” at every station stop, getting an accelerated “high” out of the discovery (and acquisition) of every new thing. Whereas, for example, African theater focuses on human knowledge and productive connections with society. Vessel has aimed to achieve this sort of connection rather than the indiscriminate accumulation or propagation of novelties.

When encountering a mode of being that is “off-measure” or imbalanced, sometimes it is necessary to react with a strong stroke in the opposite direction. So, for Vessel, the exhibition was a Western, dominant format that needed to be addressed and rebalanced somewhat given our context. Sometimes the only way to address a lack of balance, a lack of measure, is by making a move or moves in the opposite direction. As the Kenyan writer and poet Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o proposes in his book Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedoms, we need to reshuffle the center of the world.5 For Franco Cassano, the measure is a very complex construction: brave, trying to save all multiplicity by giving everything value and relevance. Our project Work in Progress might illuminate some of this thinking in our curatorial work. Rather than aiming for an exhibition, our approach for Work in Progress focused on a bus tour and the sharing of ongoing research, bringing together local issues with global protagonists.

CONCLUSION

In his book Epistemologies of the South, Boaventura de Sousa Santos chooses to start with two manifestos.6 They run in parallel: one on the right-hand-side of the page, the other on the left. One is a manifesto for good living (buen vivir) and the other is a manifesto for intellectual-activists. At the very beginning of this second manifesto, de Sousa Santos confesses that this book is probably never going to reach the people it has been written for or lead to any practical application. We would like to tell de Sousa Santos that the book has successfully reached some of the people it was supposed to reach and that Vessel has been trying to translate it into practice for years. We sincerely hope that our efforts over the last ten years, and for years to come, are worth something. Even when we feel invisible, when we are not spectacular, we are still making a contribution in the world and this, for us, is the greatest achievement of our socially engaged curatorial practice.

Footnotes

- Franco Cassano, Il pensiero meridiano (Rome: Editori Laterza, 2005).

- Franco Cassano, Southern Thought and Other Essays on the Mediterranean, trans. Norma Bouchard and Valerio Ferme (New York: Fordham University Press, 2012).

- For more information, see Mathilde Auvillain and Stefano Liberti, “The Dark Side of the Italian Tomato,” Al Jazeera, June 28, 2014.

- Sonja Dahl, “Nongkrong and Non-Productive Time in Yogyakarta’s Contemporary Arts,” Parse 2 (Autumn, 2016).

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedoms (London: James Currey, 1993).

- Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide (New York: Routledge, 2015).

Viviana Checchia is a curator, critic, and lecturer active internationally. She is currently Residency Curator at Delfina Foundation, London. Previous positions include Senior Lecturer in Fine Art at HDK-Valand, Gothenburg, and Public Engagement Curator at the Centre for Contemporary Art Glasgow (CCA). Checchia has also produced and contributed to a range of international projects including the Young Artist of the Year Award 2014 in Ramallah and the 4th Athens Biennale. For the past eleven years, Checchia has co-directed Vessel, a platform for critical discussion surrounding the cultural, social, economic, and political change created through community-based work, based in Puglia, Italy. She holds a PhD from Loughborough University School of the Arts (UK).

Anna Santomauro is a curator, educator, and researcher in micropolitics and socially engaged art. Since 2017, she has worked at Arts Catalyst in Sheffield, UK as Curator. In 2011, Santomauro co-founded Vessel, a non-profit arts organization dedicated to public programming in relation to contemporary social, political, and economic issues, based in Bari, Italy. Between 2015 and 2018, Santomauro was Public Programmer at Eastside Projects (Birmingham, UK) and Curator-in-Residence at Grand Union (Birmingham, UK). Santomauro was a recipient of the ICI/Dedalus Research Award. She is a PhD candidate at the University of Wolverhampton (UK).