A Syllabus for Antifascist Cinema (part I)

Gelare Khoshgozaran

August 2020

What images and narratives, what poetics would allow for the emergence of a version of us that invests in the dignity and well-being of all of us? What life-long training, support systems, and affective mutual aid networks would nurture our perception of freedom as the freedom of all people? What tactile or olfactory experiences would boost our immune system against the competitive market mentality governing every aspect of our lives? What would make us gentler, but more committed to preserving our ability to protect one another from violence – which at the end harms not just the most vulnerable, but all of us? What kinds of exposures, ways of relating, sensual, libidinal, erotic, poetic and material possibilities may be explored for the germination of a contemporary subject less prone to embracing fascism and more alert to identifying and rejecting it?

It is a difficult task to learn how to debunk the myth of ‘protection’ promised by policing, militarization, concrete national borders and governance by finance when our education system operates under the same structures. It is not easy to reject the seemingly only solutions available to our many problems and failures when the media and all other realms of representation are replete with propagandas of such exemplified ‘solutions.’ it is even harder to do so when we all feel vulnerable, alone and desperate individually, yet we are too afraid to come together in our vulnerability, aloneness and desperation. We are kept separate by the echo chambers of competition and individualization that tell us “You’re not good enough if you don’t compete hard enough,” “all publicity is good publicity,” that “you gotta play the game” and “run yourself like a business”: your art, your body, your love, your kinships. It is impossible to listen to a voice inside of you amidst so much noise, so much chaos and a barrage of horrifying news — under what feels like a political sleep paralysis: you can’t move, you can’t scream or wake yourself up even though you are fully aware of this nightmare.

The emergence of a subject capable of refusing these terms is a primary task of antifascism. The germination of this antifascist subject is cultivated by action, but also by an intentional aesthetics. The aesthetics of antifascism, if we can conceive of such a thing, would start with a multiplicity of images, perspectives, stories, timelines and narratives; it would emerge in fragments, a collage of imperfections and flaws, revealing the seams of its constructedness, embracing the inability of the image to be one or whole. What representations of the world, what images and narratives from whose perspective can provide an alternative to what Jennifer Barker calls “the tyranny of images generated by aestheticized politics” in her book The Aesthetics of Antifascist Film: Radical Projection? And what medium is better fit than film for the “documentation of the fragments of history” to oppose “fascism’s insistence on an aesthetic simplification of reality”?1

When pondering the aesthetics of antifascist art, I begin with considering the possibilities of cinema as still one of the farthest-reaching and free-traveling mediums for the world’s working class. Both in the digital age, and under one global pandemic of possibly more to come, film can travel with much more ease than any object can afford. This aspect of the medium, in addition to cinema’s unique ability to construct reality, is also what has made it a favorite tool of fascists, most infamously in the case of Leni Riefenstahl’s The Triumph of the Will and Olympia, among other Nazi propaganda. Today the entanglements of the US TV and Hollywood movie industry normalizing police violence, and spectacularizing imperial expansion through war and neocolonial conquest is not a secret. In this preliminary attempt to write a “syllabus” for antifascist cinema the central question was: What would make an individual more susceptible to adopting fascism as a solution to financial, cultural, psychological and political problems?

The questions of colonialism, racism, patriarchy, nationalism, policing, militarization, environmental violence and imperialism are not secondary, but central to the ongoing crisis of fascism. “It was Fanon, having escaped from Vichy-controlled Martinique to enlist in the Free French Army, who later posed the question in his decolonial classic The Wretched of the Earth: What is fascism but colonialism at the heart of traditionally colonialist countries?,” writes Nicholas Mirzoeff.2

“For DuBois,” writes Cedric Robinson, “the precondition for fascism was a civilization profoundly traumatized by slavery and racism.” “Like many ordinary Black people,” Robinson notes, “DuBois believed that the West was pathological and fascism an expression of that nature.”3

In a speech at Barnard Center for Research on Women, poet and writer, Dionne Brand states: “The triumph of capitalism has given rise to what is now called populism, but what is in fact fascism – the inability to conceal the sharing of the world and the demonizing and casting out of people who are blamed for being in the world. I have to say that it is not that I have not lived this before. It is not that this affect does not follow or hover. To me, Black people in the West have always lived under conditions of fascism. It is that in this particular moment there is an acute peak in the instantiation of fascism.”

The intent of this list is not subliminal advertising or indoctrination, but an affirmation of what Nicholas Mirzoeff calls ‘the right to look’ in his eponymous book, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality. He states:

“Confronted with the disasters of the twentieth century (and now those of the twenty-first), antifascism has had two tasks. First, to depict the reality of fascist violence as violence, and not as an artwork. Next it must offer a different possibility of real existence to confront the fascist claim that only the leader could resolve the problems of modern society. It meant claiming a place from which there is a right to look, not just behold the leader. For both W. E. B. Du Bois and Antonio Gramsci, writing in the 1930s, that place was what they called the “South,” understood as the complex and difficult place from which resistance had to begin and also as the emergent future.”4

South-looking, what follows is not a definitive or a comprehensive list but the beginning of a provisional syllabus, a list in progress, a first draft to be amended, expanded and added to, a sketchpad for a collective drawing of the contours of antifascist cinema. The selected films deploy narratives, temporalities, and subject formations in relation to various historical contexts to form a cacophony of voices and multiplicity of perspectives, relations, histories and desires for a different world. In addition to being imperfect and incomplete, the list may also appear odd at first glance. Although some of the films are situated within a specific history of fascism, others take place in different moments in history under various forms of tyranny, looking back at our collective past to better understand how we arrived here.

The selected films depict life under occupation, colonial settlement, war, segregation and racial violence, carcerality, heightened nationalism, toxic masculinity, militarism and policing. These are stories of rage and alienation, but also love and joy under structures built to annihilate them. These films depict both fascism in its brutal, absurd and violent ways, and the material means and methods of resisting, combatting and fighting tyranny – an antifascist cinema free of “exemplary” tales where “the hero is the West; the value is individual freedom (in material or spiritual terms); the interdiction is authoritarian mass movements; the villain, charismatic leaders; the misfortune, fascism; the rescuer, bourgeois democracies; the struggle, the Second World War; the moral: “The hero was imprudent, but managed to redeem himself on his own.””5

1. The Conformist (Il Conformista), Bernardo Bertolucci (1970)

Let’s start with a classic: Marcello begins working for the fascist secret police in pursuit of a “normal life” through heterosexual marriage. He is assigned the assassination of his former professor, an antifascist living in exile in Paris. (Also pictured in the header image.)

[MUBI]

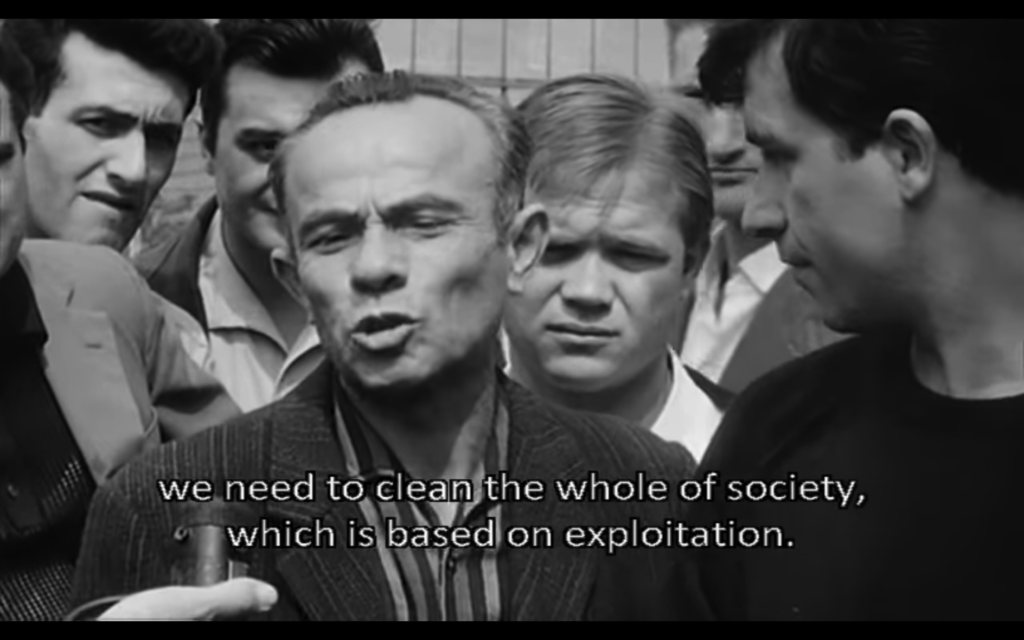

2. Love Meetings (Comizi d’amore), Pier Paolo Pasolini (1965)

No genuine conversation about antifascism, cinema or antifascist cinema is imaginable without Pasolini. While Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom is a classic in the cinema of antifascism, Pasolini’s entire oeuvre can be looked at as an exploration of a poetics and aesthetics which resist fascism, tyranny and hegemony. My Pasolini pick is a film less ostensibly engaged with direct politics: a feature length documentary made in 1965 about sex, birth, sexuality, marriage and prostitution in Italy. Beginning with asking young children how children are made, Pasolini interviews a wide range of Italians from across different class, professional, generational, age, ethnic, gender and political backgrounds about a range of social taboos, specifically the deregulation and criminalization of prostitution in Italy. The film works as a portrait of a heterogeneous Italian society with as many different responses to a single issue as the number of people interviewed. Through the fragments of responses from factory workers, poets, young kids, teenagers, and mothers, this film opens a window onto the work of a poet and filmmaker who sought the erotic in political struggles.

[YouTube]

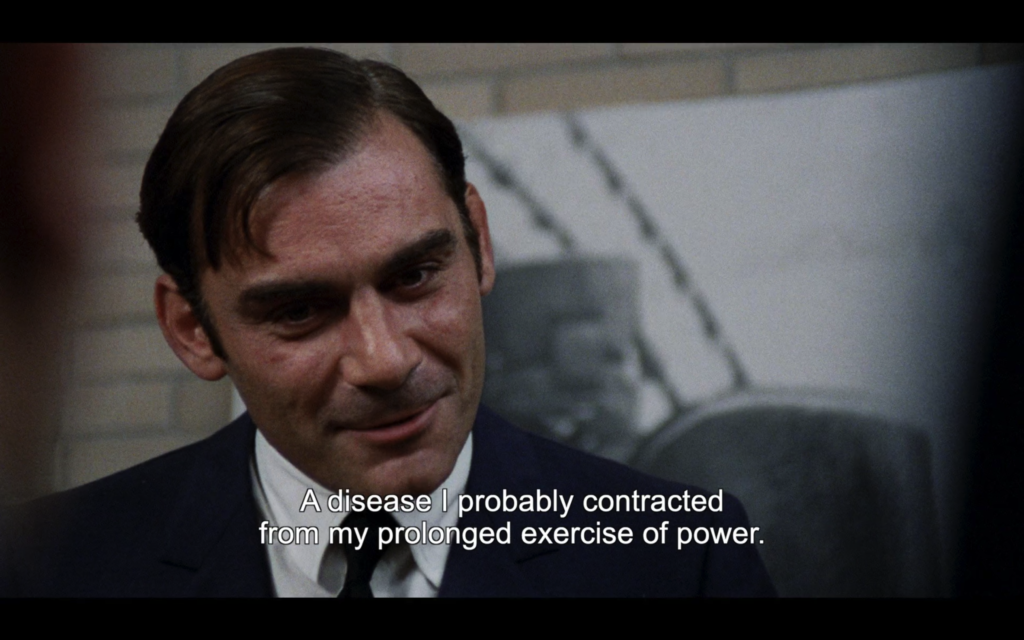

3. Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto), Elio Petri (1970)

A Roman police detective reports his own crime of murdering his lover. Predictably, he gets assigned to investigate his own crime on the same day he gets promoted from the Chief of Homicide to the Chief of the Political Division. In one of the most unsettling and resonant monologues in the film, he preambles his acceptance speech with “Gentlemen, I hope you appreciate the novelty of this meeting. It’s American style!” and continues: “The difference between common and political felonies is dwindling more and more each day…. Inside every criminal, a subversive may be hiding, and inside a subversive, a criminal may be hiding.” All along the investigation, the only living witness to his crime is his murdered lover’s upstairs neighbor: an anarchist student, Antonio Pace who is arrested in a protest and perfectly meets the criteria for a criminal suspect: a “socially and politically dangerous individual.” During an interrogation scene, when the murdered chief dares Antonio to turn him in, the young student responds: “You are here and that’s where you’ll stay, a criminal leading the repression.”

4. A Song of Love (Un chant d’amour), Jean Genet (1950)

The oldest film on the list, and the only film Genet directed; A Song of Love is a sensual love story touching on homosexuality, race, surveillance, militarized order, prisons, dreams and a concrete wall penetrated with a straw through a hole for two lovers to share a smoke (breath) between their prison cells.

[YouTube]

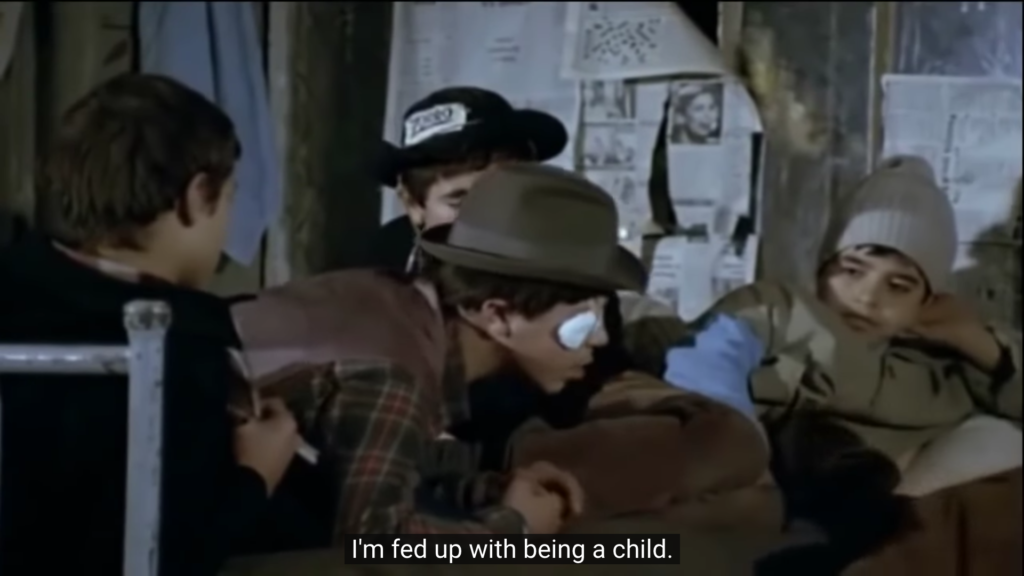

5. The Wall (Duvar), Yılmaz Güney (1983)

Yilmaz Güney’s last film was made briefly before he died from cancer in exile. Güney lived in France after escaping from prison in Turkey five years into a nineteen year prison sentence for the alleged murder of a public prosecutor in Yumurtalık. Güney’s films had been banned in Turkey since 1980 by the ruling military junta. Duvar takes place in a children’s prison ward in Turkey where a group of incarcerated children organize an uprising as their only way of being transferred to a “better” prison.

[YouTube]

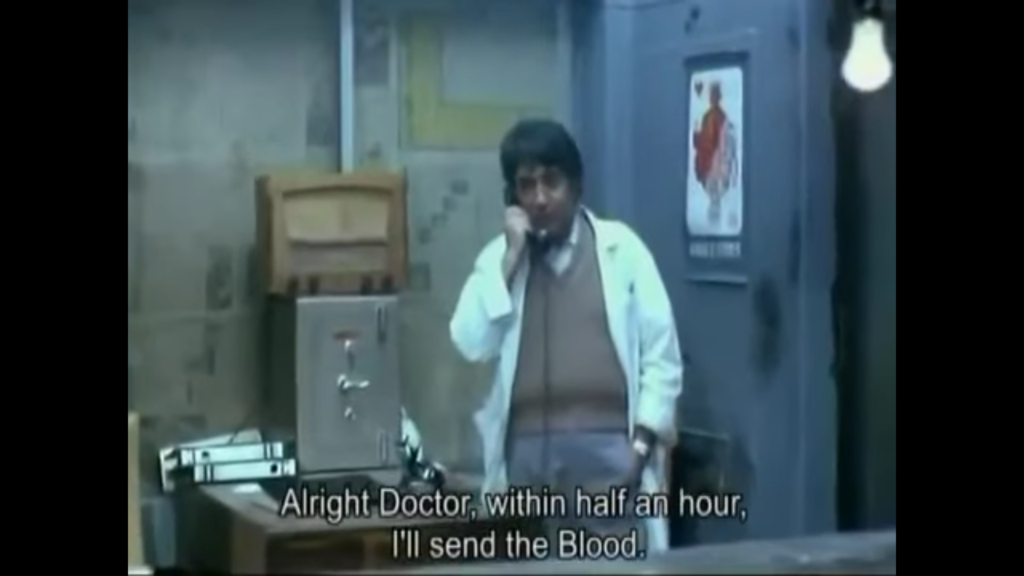

6. The Cycle, دایره مینا, Dariush Mehrjui (1978)

Premiering first in Paris, then Berlin, the film was banned in Iran for four years until released in 1978. The Cycle follows Ali, a young man with an ill father in need of hospitalization. To provide for his father and himself, Ali starts working with a bourgeois doctor who runs an underground blood bank, soliciting blood from the most forgotten strata of the Iranian urban society: the extremely poor, homeless, and drug addicts, many with infectious diseases. The infected blood is then used to treat the upper strata of the society in need of blood transfusions and gets carried from one body to another without class, ethnic, gender or other discrimination. The film is said to have provided for the foundation of Iran’s National Blood Bank in 1974. One of Dariush Mehrjui’s most acclaimed films, The Cycle is based on a play by Gholam-hossein Sa’edi. Sa’edi had previously worked with Dariush Mehrjui on Gav (The Cow), a pivotal film in the history of Iranian cinema, based on one of his short stories. One of Iran’s most influential fiction writers with great sensitivity and awareness about racial, ethnic and class dynamics in Iran, Sa’edi spent the last few years of his life in exile. In Paris, Sa’edi was in conversation with Yilmaz Güney, a filmmaker he admired, to collaborate on a film script. Sa’edi died in 1985, almost one year after Güney without the two ever meeting in person. They are both buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

[YouTube]

7. Born in Flames, Lizzie Borden (1983)

In Lizzie Borden’s dystopian sci-fi, the post socialist-revolutionary US is as sexist, classist, racist and misogynist as ever before. The film depicts, at times graphically, instances of everyday and structural violence and juxtaposes them with the more explicitly and institutionally recognizable forms of violence: the terrorist activities of The Women’s Army. Towards the end of the movie, after their two independent radio stations are burnt down, the women continue to broadcast from stolen U-Hauls and disrupt a presidential address after hijacking the state TV station and set the antennas on top of New York’s Twin Towers on fire in order to prevent the media from further disseminating lies and propaganda.

[The Criterion Channel] [Kanopy]

8. The Killer of Sheep, Charles Burnett (1978)

There are many movies from the LA Rebelion cinema that perfectly belong in this list. The Killer of Sheep takes place in post-Watts Rebellion Los Angeles. A signature of LA Rebelion defying tired Hollywood traits, the film opens a window onto small details of everyday life of a working class Black family. Stan works in a meat packing factory where he is ‘the killer of sheep.’ Scenes of preparing the animals to be slaughtered, hanging the meat, washing and cleaning up are interspersed with children playing, men meeting and making business deals, children and adults loving one another. Camaraderie, slow dancing, despair, alienation and loss are so tenderly woven into a story of everyday life on the margins of what is institutionally represented in the mainstream. Through the simplicity of its numerous tableaus, and juxtapositions such as “The House I live in” playing on scenes of children playing in the urban spaces of South Los Angeles, Burnett’s subtle cinematic critique questions the promises and core values of freedom, justice and other myths of US democracy.

[UCLA Library Film and Television Archive]

9. As Above So Below, Larry Clark (1973)

One of the most explicitly political films of the LA Rebelion, this dystopian sci-fi is set under a fascist regime. A former US marine joins an underground guerilla network of Black insurgents to organize an armed revolution.

[UCLA Library Film and Television Archive]

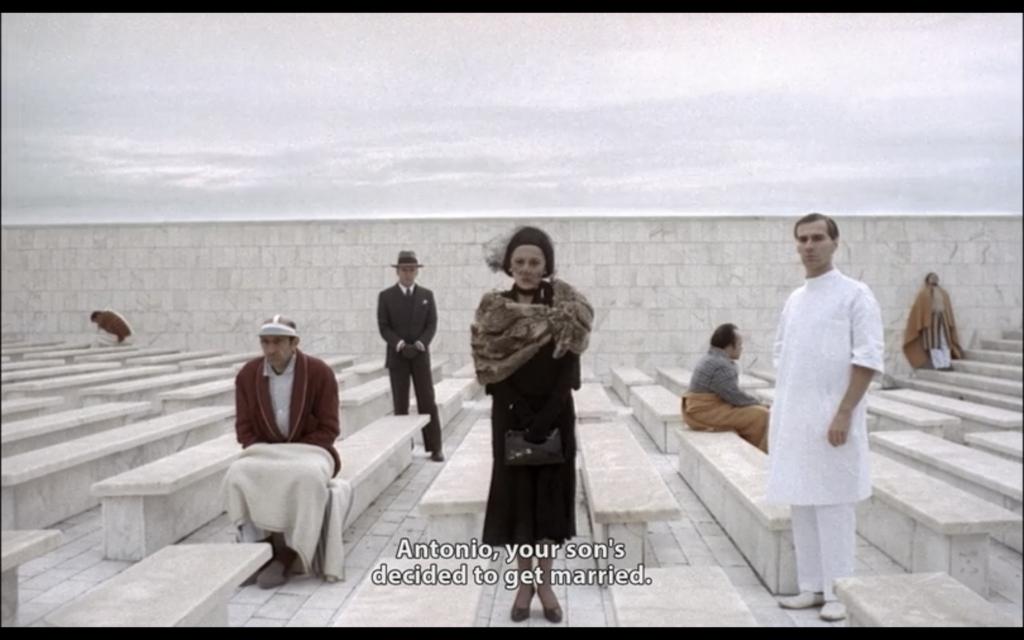

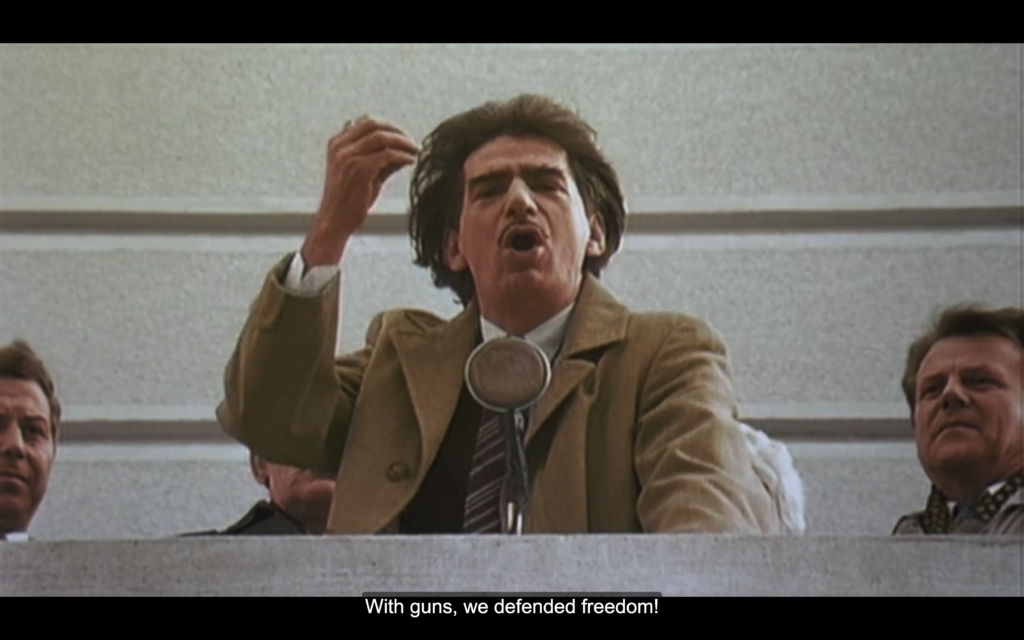

10. Underground (Подземље), Emir Kusturica (1995)

Spanning WWII, the Cold War and the Bosnian War, the movie begins with a communist taking his family and community to an underground bomb shelter during the German airstrikes on Belgrade. Time freezes for the community living underground who continues to believe the war is ongoing and the country still occupied by the German. By the time they leave the Underground, the war is already a thing of the past, distant enough to be reenacted and turned into movies. In the last scene of the film, the underground community gather together on a piece of land by the sea to celebrate the leader’s son’s wedding. Jovan, who was born and raised in the bunker, has only recently seen the world outside of the dark and drunken gun manufacturing shelter where he has lived his entire life. In a dream-like last scene, as people continue to celebrate the piece of land they’re on separates from the mainland and begins to float away. The film ends with the words “Once upon a time there was a country….”

[MUBI]

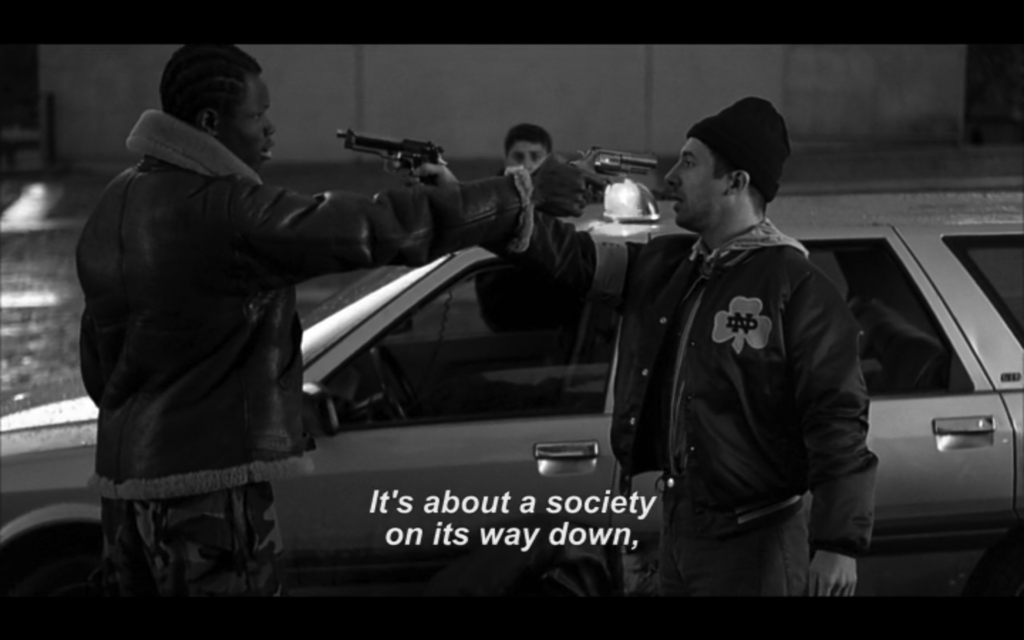

11. Hate (La Haine), Mathieu Kassovitz (1995)

In the aftermath of anti-police riots in Paris, three young men, a Jew, a North African Muslim and an Afro-French boxer, spend twenty exhausting hours in the banlieues of Paris where they live.

[Kanopy]

12. Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, Rainer Werner Fassbinder (1974)

One of my all time favorite movies with the most poetic and ever resonant title! Taking refuge from pouring rain, Emmi, a white German widow walks into a bar where the voice of Lebanese singer Sabah is playing out of a jukebox in West Germany. “I pass by here every evening and hear that foreign music” she tells the bartender, clearly uncomfortable in this dark corner of her neighborhood she had never before stepped foot. There she meets Ali, a young Moroccan migrant and frequent at the bar. Played by El Hedi ben Salem, Fassbinder’s lover, Ali develops a romantic relationship with Emmi, leading to their marriage and more.

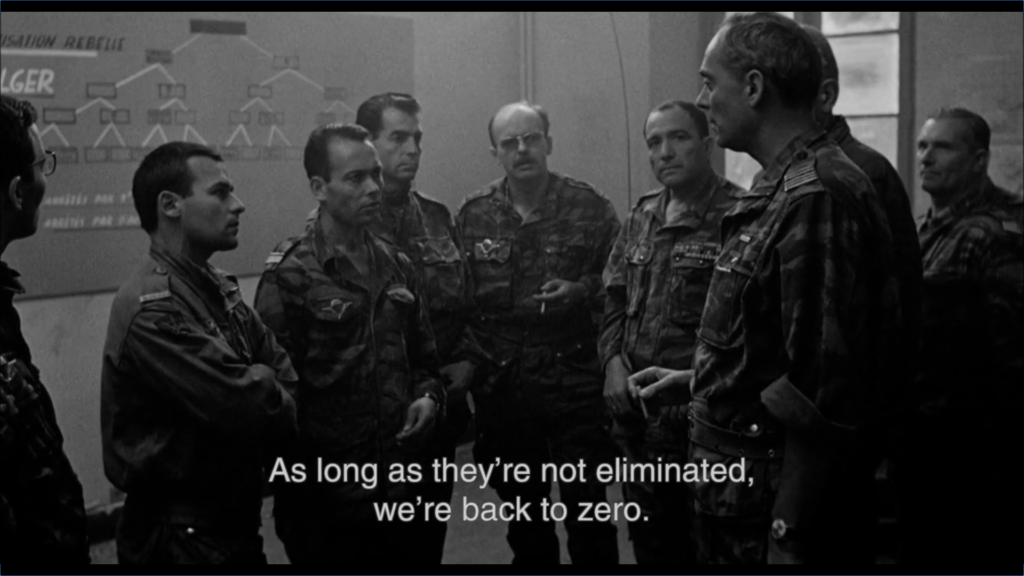

13. The Battle of Algiers, Gillo Pontecorvo (1966)

Deemed the most important political film of all times, it is not surprising to note the number of books, chapters and dissertations dedicated to more than Fifty Years of The Battle of Algiers. The film is a favorite of both anti-colonialists and generals of ‘the war on terror’ – with a screening at the Pentagon in 2003 to demonstrate how the French had already figured out successful tactics, but failed strategically to control the Arab terrorists. The Battle of Algiers is a film for all times, as long as we live in the legacies of Europe’s problems. In the words of Aimé Césaire: “The fact is that the so-called European civilization — Western civilization — as it has been shaped by two centuries of bourgeois rule, is incapable of solving the two major problems to which its existence has given rise: the problem of the proletariat and the colonial problem: that Europe is unable to justify itself either before the bar of “reason” or before the bar of “conscience.”

[Kanopy]

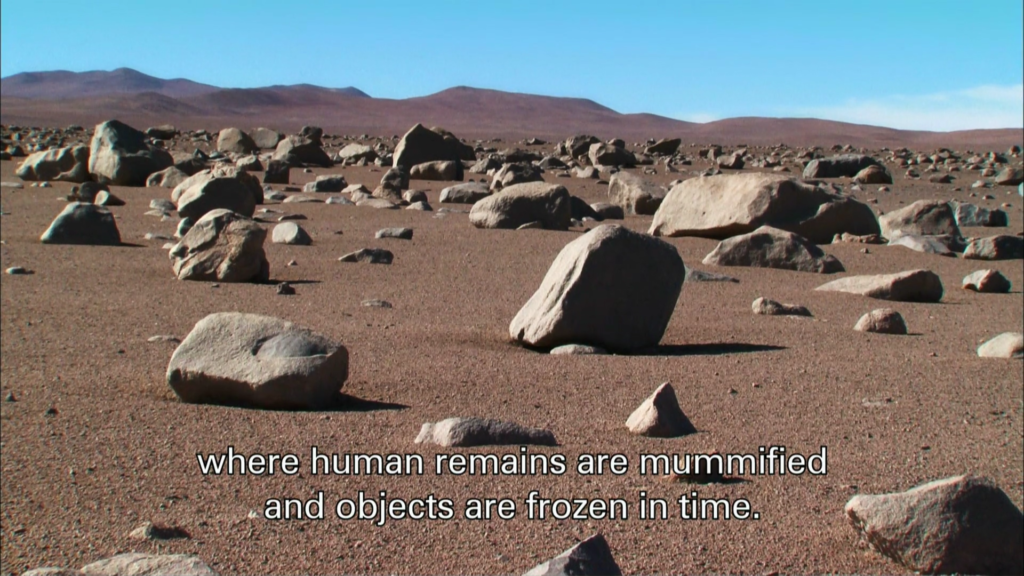

14. Nostalgia for the Light (Nostalgia de la Luz), Patricio Guzmán (2010)

In the above cited chapter, Antifascist Neorealism (The Right to Look), Nicholas Mirzeoff reminds us: “The practice of “disappearing” anti-government activists, meaning having them killed and disposed of in secret—was begun by the French during the revolution and later exported by them to Latin America, most notably in Argentina and Chile. Such practices, far from forming a decolonized visuality, epitomize the secrecy of the police in separating what can be seen from what must be declared invisible.” One of the most philosophical documentaries about the history of the ‘disappeared’ and the atrocities of the US backed military dictatorship in Chile (among other countries in South America), Nostalgia for the Light is multidisciplinary poetry: “A revolutionary tide swept us to the centre of the world….around the same time, science fell in love with the Chilean sky. A group of astronomers found they could touch the stars in the Atacama desert. Enveloped in stardust, scientists from all over the planet created the biggest telescope in the world. Some time later, a coup d’etat swept away democracy, dreams and science.” The astronomers’ looking up at the sky parallels a group of women whose loved ones who had disappeared during the dictatorship were kept in concentration camps, tortured and killed in the Atacama desert—their bones preserved by the salt in the dry sand where nothing ever grows. Nostalgia for the Light cuts through the layers of violence that run parallel to the strata of the earth: “A people without memory are a people without a future.”

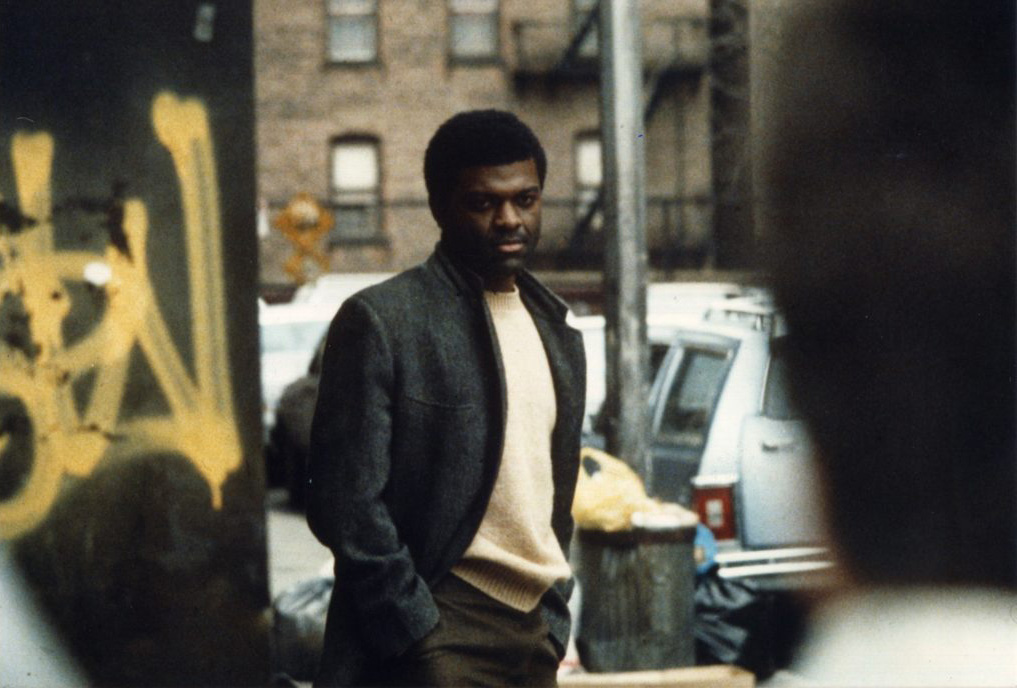

15. Haitian Corner, Raoul Peck (1987)

A carpenter by day and poet by night, Joseph is a refugee in Brooklyn, NY who has fled Haiti where he was tortured as a poet and activist under the dictatorship of Jean-Claude Duvalier. Living in exile in New York, one day he recognizes the voice of his torturer.

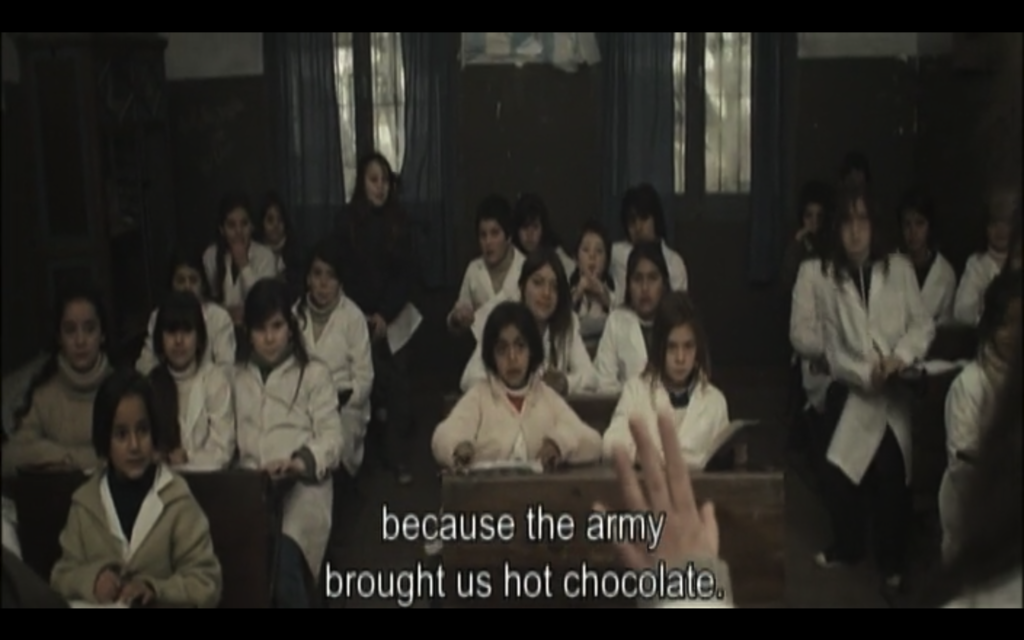

16. The Prize (El Premio), Paula Markovich (2011)

Paula Markovich’s autobiographical film is set in San Clemente del Tuyú in Argentina where she spent much of her childhood. Set during the military dictatorship in Argentina, a young mother and her seven year old daughter hide in an abandoned beach house. One day representatives from the national army visit the small rural school to promote a writing contest about the Argentine nation. The conflicted seven year old writes an essay describing how the military has kidnapped her father, causing debilitating panic to her mother. In one scene, as the child witnesses her terrified mother burying “political” books in the sand, she imitates her by burying one of hers “for play.” The water washes over both of their buried books.

17. The Chronicle of Disappearance (سجل اختفاء), Elia Suleiman (1996)

Elia Suleiman’s first feature film tells the story of the filmmaker himself who stars in the film under his initials, E.S. after returning from New York to Palestine. The film is made with a cast almost entirely of his family, relatives and other nonactors. Structured as a chronicle, in different chapters of multiple vignettes, the film is ripe with absurd humour that is the signature of Suleiman’s films. Made and released after the Oslo Agreement, it depicts mundane everyday scenes of life, leisure and business in Palestine with a recurring trait of mocking authority, especially the Israeli police.

[YouTube]

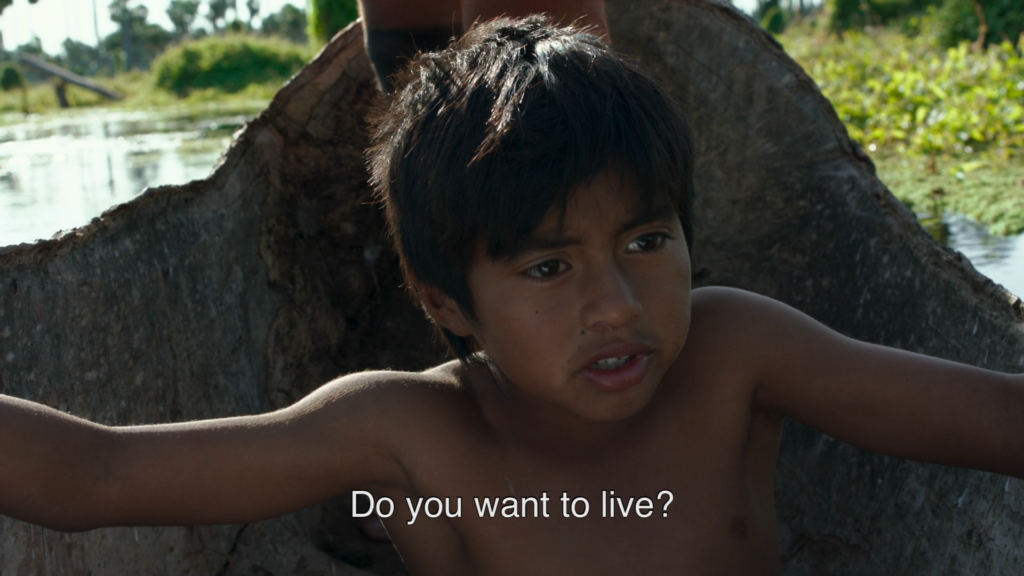

18. Zama, Lucrecia Martel (2017)

It is perhaps an odd choice to have a period film set in the 18th century in a list of antifascist films. Lucrecia Martel’s latest film, Zama starts with Don Diego de Zama, a Spanish functionary overhearing a group of indigenous women bathing and practicing the equivalents of Spanish words in Guaraní. It is a rare historical cinematic depiction of Spanish colonial rule in South America.

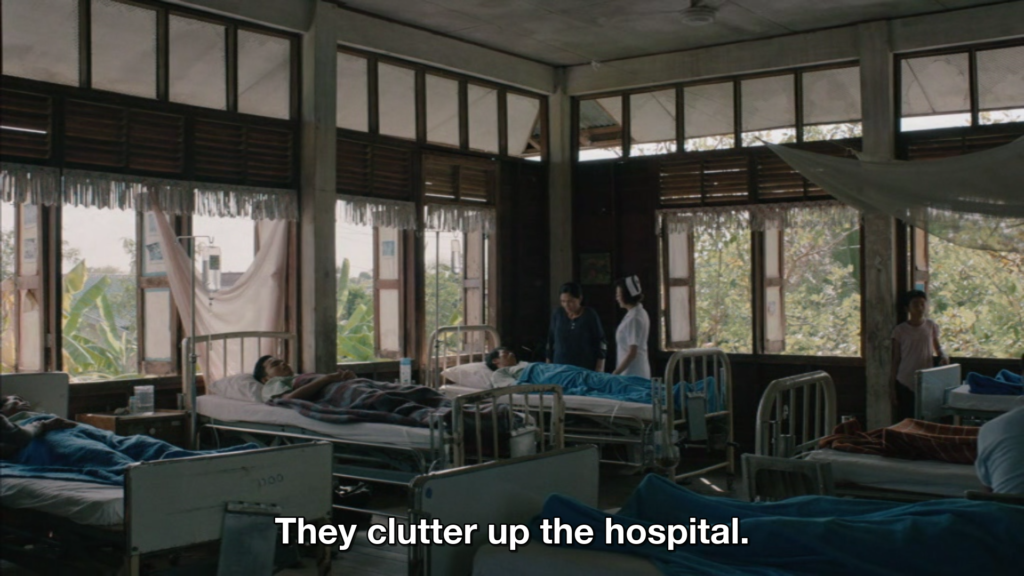

19. Cemetery of Splendour, Apichatpong Weerasethakul (2015)

Jen returns to her former school turned hospital where numerous soldiers with a strange disease are comatose for days at a time. There she is introduced to a woman “who helps the police with her ability to communicate with the spirit of those murdered and missing.” Jen, who’s married to Richard, an American army veteran she has met on the internet, spends time with one of the ill soldiers during all his waking hours. Conversations throughout the film are interrupted by the soldier’s sudden falling asleep.

20. The House is Black (خانه سیاه است), Forough Farrokhzad (1963)

In pre-revolutionary Iran ruled by a monarch, the avant-garde poet and filmmaker Forough Farrokhzad takes a trip to one of the most forgotten corners of the country, a small village where the patients with leprosy are quarantined. Reminiscent of Che Guevara’s volunteering at San Pablo leper colony, she submerges herself in the community to document the tender moments of life, intimacy, beauty and laughter.

[YouTube]

21. Endless Poetry (Poesía sin fin), Alejandro Jodorowsky (2016)

Jodorowsky’s 2016 autobiographical fiction film bears an undeniable resemblance to the first segment of Bolaño’s 1998 novel, The Savage Detectives. Young Alejandro leaves his family to merge himself in a new life surrounded by poets, writers, homosexuals, outlaws and bohos in Santiago de Chile. During Carlos Ibáñez del Campo’s second dictatorial rule in Chile, Alexandro, an antifascsit poet, leaves his hometown for Paris. Only in a Jodorowsky movie you can find a character, the poet’s mother, who communicates in an entirely different genre throughout the film: the musical!

Footnotes

- Barker, Jennifer Lynde. The Aesthetics of Antifascist Film : Radical Projection, Taylor & Francis Group, 2012. ProQuest Ebook Central, Link.

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. The Right to Look : A Counterhistory of Visuality. E-Duke Books Scholarly Collection. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011. p. 239

- “Fascism and the Response of Black Radical Theorists.” In Cedric J. Robinson: On Racial Capitalism, Black Internationalism, and Cultures of Resistance, edited by Quan H. L. T., by Robinson Cedric J. and GILMORE RUTH WILSON, 149-59. London: Pluto Press, 2019. Accessed July 17, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctvr0qs8p.16.

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. The Right to Look : A Counterhistory of Visuality. E-Duke Books Scholarly Collection. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011. p. 232

- “Fascism and the Response of Black Radical Theorists.” In Cedric J. Robinson: On Racial Capitalism, Black Internationalism, and Cultures of Resistance, edited by Quan H. L. T., by Robinson Cedric J. and GILMORE RUTH WILSON, 149-59. London: Pluto Press, 2019. Accessed July 17, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctvr0qs8p.16.

Gelare Khoshgozaran is an undisciplinary artist and writer who, in 2009 was transplanted from street protests in a city of four seasons to the windowless rooms of the University of Southern California where aesthetics and politics were discussed in endless summers. Her work has been presented in solo and group exhibitions at the New Museum, Queens Museum, Hammer Museum, LAXART, Human Resources, Visitor Welcome Center, Articule (Montreal), Beursschouwburg (Brussels), Pori Art Museum (Finland) and Yarat Contemporary Art Space (Baku, Azerbaijan). She was the recipient of a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant (2015), an Art Matters Award (2017), the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award (2019), and the Graham Foundation Award (2020). Her essays and interviews have been published and are forthcoming in contemptorary (co-founding editor), The Brooklyn Rail, Parkett, X-TRA, The Enemy, Art Practical, Ajam Media Collective, The LA Review of Books and Temporary Art Review, among others.