You Can’t Play Here – Or, Forms of Infinite Play

Lital Khaikin

May 2022

Children’s Games (1560), an oil painting by Flemish Renaissance artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder depicting an entire town of adults engrossed in children’s games. Courtesy of Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien.

How the young are tempted and betrayed

into slaughter or conformity

is a turn of the mirror

time’s question only.

—Audre Lorde, Generation (1976). 1

Grow Up!

From one Great Depression to the next, the ways in which children play in public spaces have constricted over the past century, from a free-range anarchy and “the world as playground,” to playing areas that deter both escapees and intruders with signs, fences, and rules. By its very definition, play insinuates that there is a beginning and end to this activity, that there are right and wrong forms of making and doing play, and that it is not, in fact, an infinite gesture.

Across North American cities and suburbs, spaces of play are shaped by grids, scaffolds,2 and primary-colored plastic menageries that have more or less defined purposes. Slides, bars, seesaws, various spinning objects: there are clear limitations to how you can move and interact with play structures, comfortably abiding by the principle that, even in these cordoned pits of leisure, form follows function.

While the objects of play may determine the behavior of play, it is the concerns of adults that are merciless in shaping the places of play. From the privilege of suburbia and gated communities to histories of segregation, playgrounds are powerfully representative of the economic and psychic divides across race, gender, class, and physical mobility. Before even the chance of becoming the kingdom of children, playgrounds become extensions of racism and colonialism, drawing the territories of exclusion both within and outside of their boundaries.

Issues of accessibility and racial justice in play are again being brought to the foreground in tandem with deepening scholarship on healthy human psychological development, neurodiversity, and early childhood trauma – even as these same issues of access evolve in complexity, as with new playgrounds and public park renovations signaling rising property values and gentrification. A new playground that is being constructed in Montreal’s Parc La Fontaine is just one example of recent projects that integrate physical accessibility for children with reduced mobility and aim to diminish visual overstimulation for autistic children.

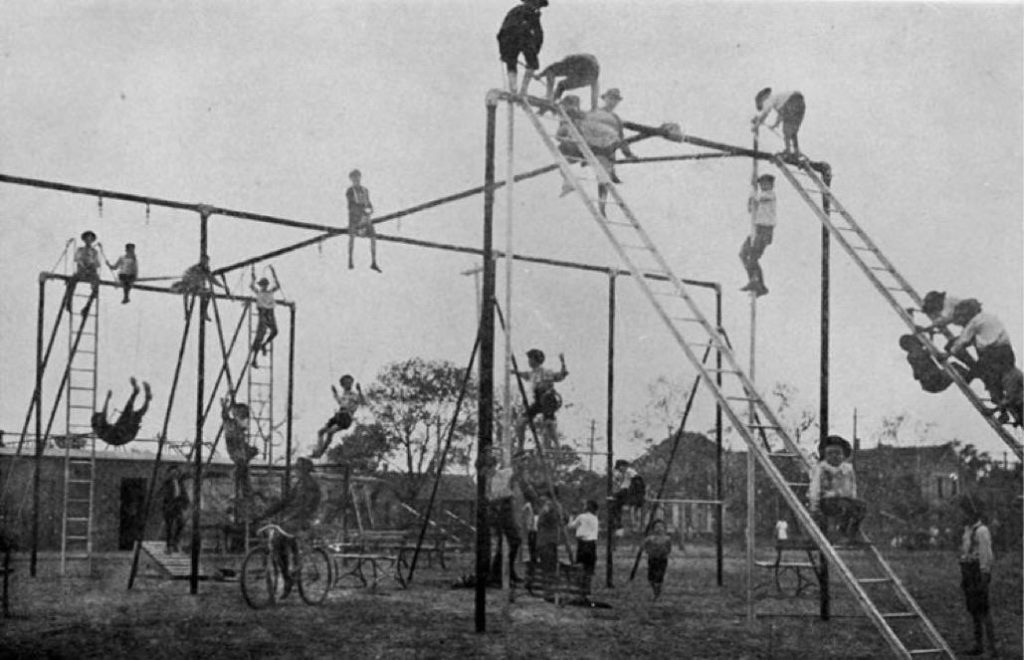

The thrill of a playground from 1900, when play meant a potential confrontation with life, death, and loss of limb. Black-and-white photo of Trinity Play Park (1910s), photographer unknown. Courtesy of Dallas Public Library.

Children burn things at Notting Hill Adventure Playground. Black-and-white photograph by Donne Buck (1960). Courtesy of V&A Museum of Childhood Archive, Donne Buck Collection, London.

Donne Buck’s campaigns in postwar London aimed to bring playgrounds to poor and working-class neighborhoods that had been demolished in the Second World War with an anarchic irreverence that empowered children to build (or destroy) their own environments.3 Also in the 1950s, when Black children were arrested for playing in white-only playgrounds in Washington, DC, access to play figured significantly into the civil rights movement with children leading protests and sit-ins.4 The imprint of apartheid can also be traced into the West Bank and Palestinian refugee camps, where children rarely have a safe place to play.5 Already besieged by Israeli military occupation and bombing of residential and civilian buildings, Palestinian children must navigate the contradictions of either the complete absence of safe play or, where there is access to space, the assault of surrounding distress, rage, and destruction on the psyche in a way that makes play inseparable from trauma.

Neither can the play structure escape the iconography of neoliberal globalization: yes, the polyethylene slide is a symbol of empire, and so too are the Winkel rattles and baby musical mats gracing Amazon’s most popular toy selections. From Pleasantville, Iowa and the manicured lawns of Montreal’s Outremont, to the suburbs of Jakarta and Bucharest, trademarked systems of play are channeled through global supply chains, imprinted by the traces of oil wars, special economic zones, labor camps, and industrial pollution. In such a way, play is already contaminated by the preferences of production and the forces of militarism, always already negotiating an unlivable world.

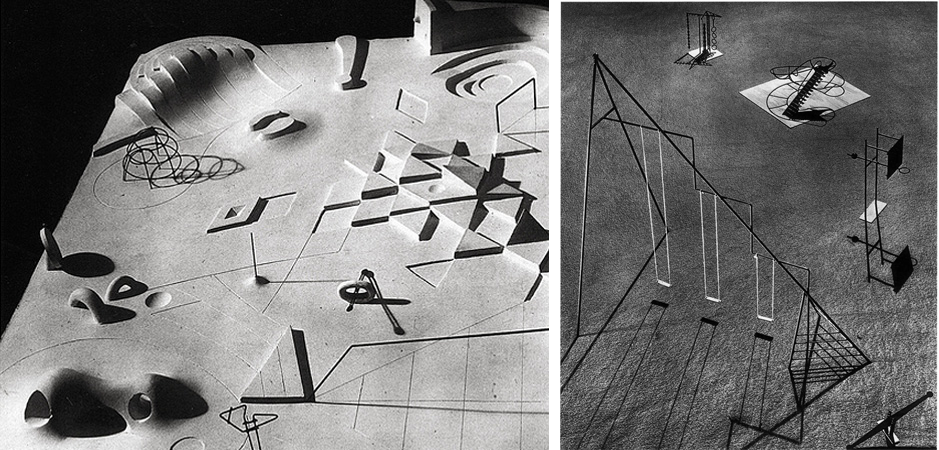

Left: Noguchi’s UN playground model. Black-and-white photograph (1952) by Charles Uht. Courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum. Right: Playground equipment for Ala Moana Park in Honolulu, Hawaii (1940). Black-and-white photo of model courtesy of Catalogue Raisonné.

The influence of the play structure on the type of play, bodily movement, and interpersonal relations was poetically explored by architect Isamu Noguchi in his contoured playgrounds.6 Significantly, Noguchi’s playgrounds emerge from a period of personal evolution from the figurative to abstraction influenced by his time in voluntary internment at the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona, a concentration camp for Japanese citizens and residents in the western United States in the 1940s. Informed by his observations on the influence of prison and environment more broadly on the psyche, Noguchi’s play structures pushed the boundaries between prescribed and interpretive movement. His sculptural objects allude to familiar forms of play while remaining suggestively abstract. This ambiguity allows for an unscripted exploration, acting as a punctuation on space and a possibility rather than a dictate.

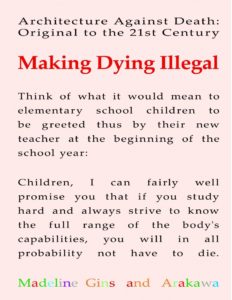

Cover for Making Dying Illegal – Architecture Against Death: Original to the 21st Century (New York: Roof Books, 2006).

The role of the prepackaged playground in shaping children’s psychic development poses many of the same questions for a world of suffering and psychically starved adults.7 Through their Reversible Destiny Foundation, Shusaku Arakawa and Madeline Gins explored the relationship between the body’s spatial perception and its generation of meaning. The crisis of the scripted body is understood as “pre-destiny,” a person’s behavior, responses, gestures, and pace known to be limited by the formulas of age, mobility, efficiency, potential, capital. In the vein of Noguchi’s experiments, Arakawa and Gins’s project responded by provoking play through the otherwise ordinary environment of a home.

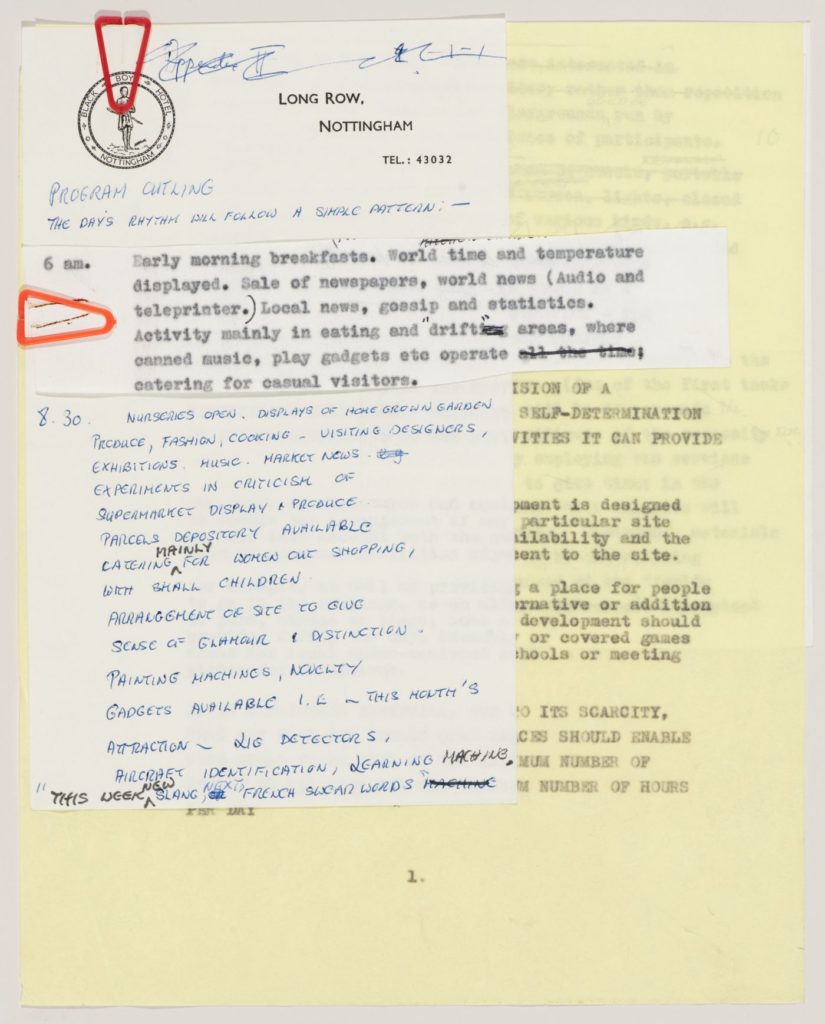

Texts for a program outline and text for a proposal for use of public open space as a pilot project for major aspects of the Fun Palace. Ideas span early morning breakfasts, “drift” areas, French swear words, and a “sense of glamour and distinction.” Digitized manuscript (1964) courtesy of the Canadian Centre for Architecture.

More radically, Arakawa and Gins proclaimed: “We have decided not to die.” This declaration underlies the heart of the Reversible Destiny project, whose wacky lofts take on rather serious dilemmas of the interconnectedness of built environments with mental and physical health, of the scripted ways in which we move through space, and, growing out of this choreography, the silent disappearance of both place and self from the living world.8 The Reversible Destiny Foundation has sought to integrate play into living, turning homes that become invisible in their banality – and into which the vital human being, in turn, disappears – into environments that provoke attention through interpretation and making one’s own meaning in place. To refuse to die is to refuse this disappearance, to deeply refuse death within life.

Reversible Destiny Lofts, Mitaka, Tokyo (In Memory of Helen Keller). Completed in 2005, the Mitaka lofts were the first residential works of “procedural architecture,” each apartment shaped around a circular room. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Reversible Destiny Foundation.

This provocation toward vitality takes on a metaphysical slant in hide-and-seek, simple and subtle but imbued with a magical shade of thinking that situates one both alongside and beyond objects, environment, self, and other. The game is laced with an artistry in the interpretation of the body in space and the latent possibilities of an environment, the sense and limits of self and of imagining the sensing and witnessing by – as – the other.9 In the investigation of the self’s simultaneous experience of visibility and invisibility, one is always in flow with the unknown, charting the topographies of light, while forming a present absence alongside the shadows. This miniature adventure into limitlessness has much to reveal about the relationship between the boundaries of exterior and interior worlds.

In her book Architecture from the Outside (2001),10 philosopher and feminist theorist Elizabeth Grosz examines the experience of the “outside” as an event that triggers thought and thinking. Inquiring into the changeable nature of an interior in relationship to both the potentialities and the “convolutions and contortions of an outside,” she writes: “The boundary between the inside and the outside, just as much as between self and other and subject and object, must not be regarded as a limit to be transgressed so much as a boundary to be traversed.”11 So it is that the spaces and structures of play can mirror the disturbances of psychic zones in a world that is deeply impoverished of play and yet is so desperate for its recovery.

Early play is life “testing” the world, creatures traversing the possible, exploring and confronting the void of the unknown, expectant with discovery. In this sense, play is also a flirtation with fear, creeping along the edges of a supernatural landscape that hovers delicately between safety and traumatic catastrophe. While its inconclusive nature calls for never quite touching upon one or another of these thresholds – always in between and not-yet – play disintegrates in the moment it touches upon catastrophe. It is defeated and undone by brutality, as in Cain’s Book (1960), where Alexander Trocchi, the archetypal tortured artist – which is to say, the conqueror of the useless12 – wrote: “When the spirit of play dies, there is only murder.”13

Equally, this presents the problem of reconciling with the other boundary, where a totally fulfilled utopic safety just as easily negates the pursuit and investigation that is the essence of play. Where there is then no investigation, no striving and no question, there is no creativity. Such a parallel can be found in Theodor W. Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory (1970): “The art of absolute responsibility terminates in sterility . . . absolute irresponsibility degrades art to fun.”14 He further writes: “Only when play becomes aware of its own terror, as in Beckett, does it in any way share in art’s own power of reconciliation.”15 In this suspended space of neither-nor, the nowhere, the no-place, is there a way to reconcile play on the edge of the limitless with the care that calls for a world in which it is safe to wander?

-

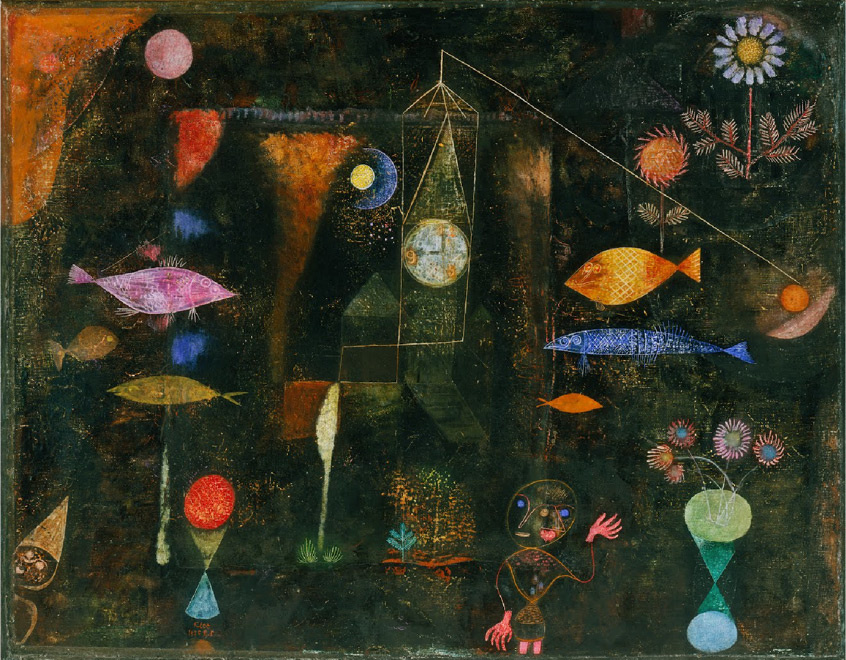

Fish Magic (1925), an oil and watercolor painting by Surrealist painter Paul Klee, in which the forces of nature and the human products of thinking merge into a spontaneous and mystical coexistence. Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Very Serious Matters of Consequence

Like the zones of play designated for children, the world of grown-ups is divided by clear distinctions between moments of play and seriousness. Time, at once a most precious language and the greatest oppressor, is treated as another resource to be extracted, each phase of life little more than a prolonged moment in the service of capital. The human creature enters into the ever-shifting milestone of adulthood, charged with the task of not only growing up, but remaining grown up in a world where regression is monstrous.

Recalling again how play approaches the power of reconciliation through an awareness of terror, the adult play mutates from inquisitive discovery into the act of flight toward a state of being that makes life livable. For the adult whose existence is practically and emotionally reliant on their work, be it the means of survival or the scaffold of identity, a profound void extends out of the loss of meaning in labor, the horror unfurling in a world that is forgetting how to play.

The emotional vacuum accompanying the automation of work was anticipated by Viktor E. Frankl in his treatise on logotherapy and meaning-making, which significantly deviated from the emergence of the pharmaceutical industry and the dominant practice of pathologizing the complex dimensions of human suffering. Frankl wrote presciently about the trauma to the psyche that would inevitably unfurl with the loss of human labor and reliance on the automation that would “probably lead to an enormous increase in the leisure hours available to the average worker.”16 Drawing a parallel to the phenomenon of “Sunday neurosis,” this gradual transition would open an “existential vacuum” that had been previously covered up by the attachment of identity to work.

And what a haunting crowd awaits on the margins: the dance of coping and denial that compartmentalizes work and life, the fragmentation of a meaningful identity, the abdication of principles, the inner decay sown by guilt and shame, the cold surrender to sadism, the comfortable cages where we are simply making do.17

Hand in hand with automation, the workplace of the post-financial crisis is marked by attempts to alternately reconcile or outright deny the polarities of labor and leisure. Traces of radical subversion and protest, inconformity, work refusal, loitering, stealing back time, and hanging out are subtly absorbed back into the culture of work, as “hacks” in service of productivity, where workers are “chill,” play is never really play, and informality teases the possibility that work is never really work.

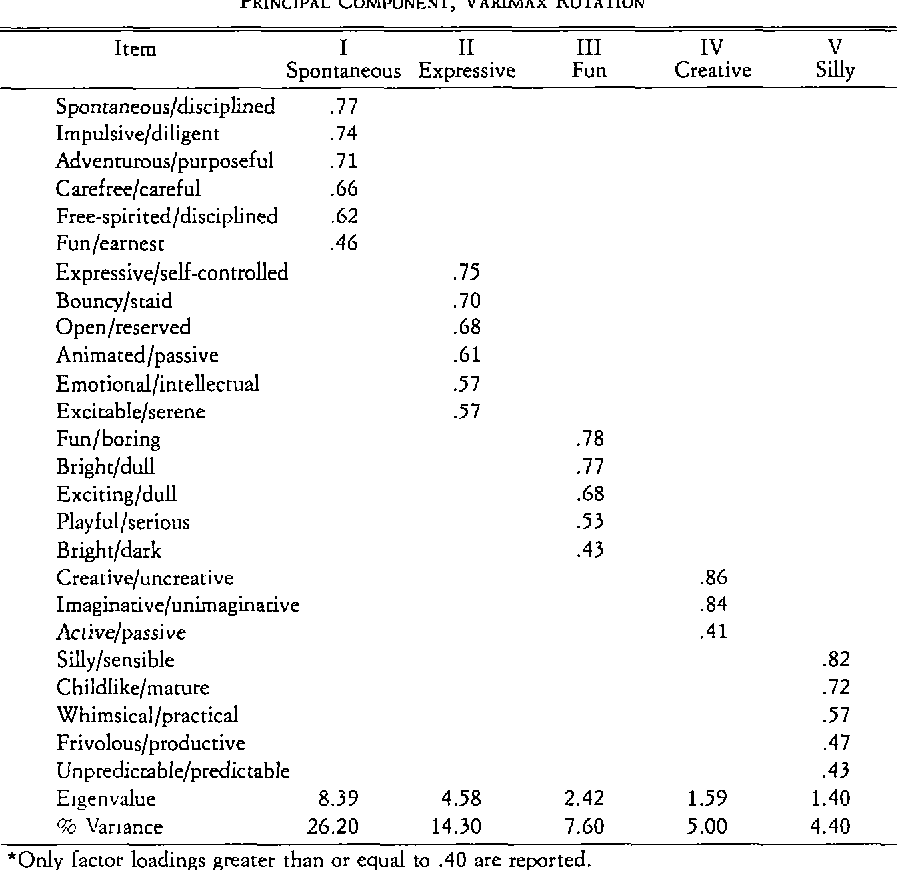

A table showing “principal components” in an assessment of adult playfulness, posing many questions about how the implications of darkness, bounciness, and frivolity in relation to “fun” may be (mis)read through hegemonic cultural norms. Mary Ann Glynn and Jane Webster, “The Adult Playfulness Scale: An Initial Assessment,” Psychological Reports 71 (1992): 103–83.

Championed by Silicon Valley, and adopted into the parlance of “learning organizations” and “progressive-minded managers” alike, corporate psychology cynically encourages flexibility, adaptability, and creativity in companies’ built and cultural environments with the end goal of optimizing efficiency and deliverables.18 Instruments developed from the 1970s onward, like the Playfulness Scale for Adults, attempt to measure predispositions and personality traits in order to quantify the complexity of human experience and expressive norms into something ultimately useful for productivity. Process models for designing play propose any number of “experiential qualities” like exciting puzzles and exchanging humor with clients to enhance work activities. Office spaces have moved toward integrating more playful variations on workspace, from modular design to “creative co-working” and familial work-live studios. Brainstorming sessions for company branding, policy documents, and consensus agreements on creative initiatives are made “fun” with marshmallow pyramids, scribbling sessions, and sticky-note collages. Ping-pong tables, arcade games, and bubble soccer outings practically seduce workers into camaraderie lest too much ressentiment results in a missed grant report.

-

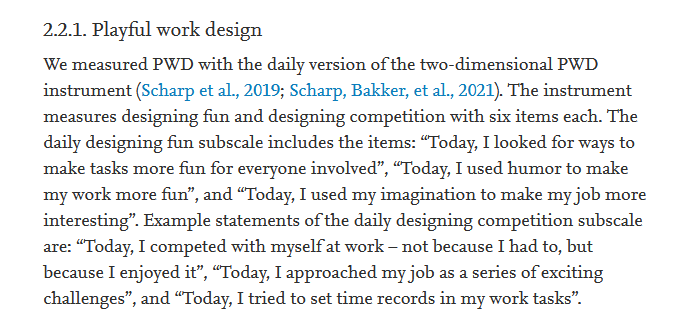

Excerpt from a study on “Playful Work Design.” Yuri S. Scharp, Arnold B. Bakker, and Kimberley Breevaart, “Playful work design and employee work engagement: A self-determination perspective,” Journal of Vocational Behavior 134 (April 2022), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2022.103693.

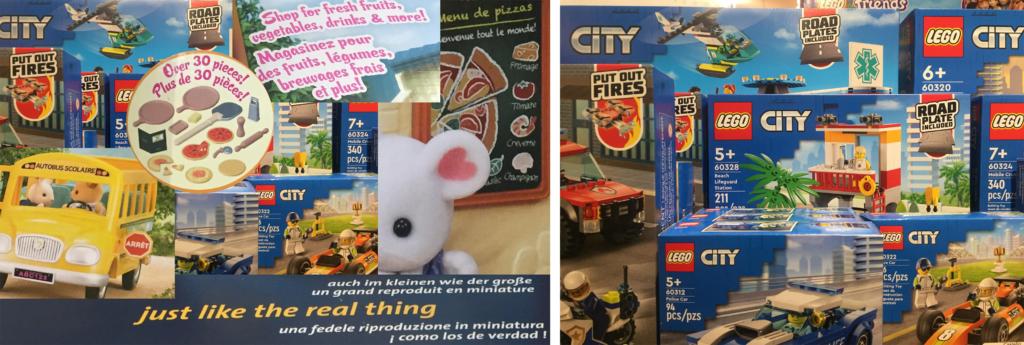

The utilitarian blurring of boundaries between work and play has easily precipitated back into the hyper-specificity of children’s toys that mimic the tools of production and formulas of labor. Much like laptops, cars, and shoe sizes – and the transnational stamp of plastic play structures – globalization has led to a standardization of toys. Wooden blocks that can be shaped by a child’s imagination and cultural references have given way to Lego sets that extend the influence of a franchise into the minds of toddlers everywhere. Plastic tanks and warplanes are a sleight of hand to fire up the imagination of future engineers, the tools of mass murder made ordinary and occupying the fragile imaginative space before living needs to conform to ways of making money. Play-kitchens, play-shopping, play-cafes are modeled after future workplaces and places of service. An Easter Bunny building kit will only ever yield an Easter Bunny.

While play can always be seen as an evolutionary necessity, tempting praxis, it is degraded when it is wholly in service of a sterile progression toward usefulness and complacency, acclimating to the spaces and objects of consumption and the dynamic of regulations, restrictions, and supervision. These codified toys and games ensure that the most impressionable and malleable minds are indoctrinated as early as possible into the service of capital, aging into fun-yet-diligent, creative-yet-sensible adults who always know what to do, but without the picture on the puzzle-box are unable to remember how to play.

Photo collage of generic toy packaging depicting models of various adult activities and places like pizza parlors, grocery stores, and police cars (2022). Photos courtesy of the author, who visited a toy store one fine afternoon.

Irregardless!

“Parents stink,” Janey opens in Kathy Acker’s Blood and Guts in High School (1984), where abandonment is the “roar of the universe” that little girls learn to understand as love.19 Acker’s child trips uneasily into the vice of materialistic society, crucified yet redeemed through the totality in which she throws herself into the only thing that life seems to make impossible: living. “Good is bad,” she writes. “Crime is the only possible behaviour.” Like Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince who meets the businessman and the geographer, the salesman and the tippler, all comfortable with their occupations and forgetting the rest of the universe, Janey and so many other Janeys looking for a rose are used, beaten up, fucked and forsaken to the world beyond the playground – one made of taxes, police, and the CIA, scholars, salesgirls, and presidents, repressed hysterias pouring out when the recess bell rings.

Only a few short years after Acker’s teenage Janey ran away from the capitalists with her lover Jean Genet to Tripoli, Viktor E. Frankl wrote in the postscript for his 1984 edition of Man’s Search for Meaning about the “no future” generation, a generation touched most immediately by the Cold War, the reverberations of Vietnam, Korea, and the Second World War, and the cusp of globalization that was not yet saturated on the internet.20 Nearly four decades later, the tectonic pressures of planetary catastrophe, financial collapse, exaggerated social isolation and fragmentation, and endless war pose a more immediate and encompassing challenge for the “tragic optimism” he called for as a balm for this despair. Born into shadows and panic, the young are asked to bear the world far sooner and far more entirely, so that in navigating the immensity of interconnected trauma that is made visible and known through both the sensory environment and mediated by technology, childhood itself is in a process of disappearing from the most intimate vestiges of the psyche.

Contemporary psychological literature emphasizes healing the inner child as a crucial part of trauma therapy, recognizing that the problems of grown-ups are really the wounds from our most vulnerable states. The work of Gabor Maté, for example, points to the crucial links between early childhood abuse and self-abusive behaviors in adulthood, like addiction, repression of emotions, self-imposed isolation, and recreating dynamics of proximate separation in relationships.21 Judith Herman’s canonical volume Trauma and Recovery (1992) traces the emotional and neural pathways that are tangled into adulthood from a childhood where chronic abuse is impossible to escape, destroying any sense of safety in the world.22 Pete Walker’s Complex PTSD: From Surviving to Thriving (2013) charts recovery from “soul murder”23 that children experience at the hands of parents who physically, sexually, and psychologically abuse them.24

Yet, as much growing emphasis as there is on healing the inner child and recovering play in adulthood, that emphasis is more often on making a person conform to neoliberal structures and logics with the intention of making the individual once more into a productive and exploitable resource. Formulas, steps, and manuals outline how play can reintegrate the lost and broken parts of a person into a coherent self – one that, at the very least, should make sense to others. When, or even if, that inner child is dealt with, the world outside remains just the same as it ever was, with its infrastructures of isolation, the acceleration of technologies of violence, and the very sources of trauma still cycling in and out of the body. It’s just that the inner child can now go to sleep in peace, as the adult maybe takes a tranquilizer and shows up.

Still of the protagonist from Jean-Claude Lauzon’s film Léolo (1992), about a boy who finds refuge in imagination from his troubled working-class family in Montreal.

The insistence on life as play – a grand jeu – has never escaped the stigma of irresponsibility and an underlying deficiency, considered whimsical eccentricity at its best and a threatening pathology at its worst. Encumbered with pathology and punishment, play is treated as an adolescent behavior that is unacceptable in the adult world, while playfulness and lighthearted mischief, when they are not harnessed for productivity, are suspicious symptoms of dysfunction (histrionic, maladaptive, immature) rather than expressions of curiosity and vital engagement with a world of mystery that is so fantastically large. So long as play is not with life itself!

Still of the protagonist Jeliza-Rose from Terry Gilliam’s film Tideland (2005), about a girl from a drug addict family who lives a fantastical life alone in a desolate prairie.

The ill-conforming citizen who doesn’t adjust to career trajectories and business incentives. The drifter who refuses, in more than one way, to settle. The perpetually experimenting, remaking, redoing, reworking. These big and small children live in worlds of stark contrast to the neat suburban play structures, to a world so fluent in fences. To make sense of the brutality into which they are thrown headlong, they live amid the tomato carts of Léolo or in the sun-drenched prairies of Tideland, fighting windmills in the plains of La Mancha, where the divide between play and the world of adult violence, the absurdity of survival, has long since been shattered. It has always been clear that there are no safe containers, perimeters, color-coded schemes, or rules of the game, demanding no less than magic-making – a profound expression of humanity for a creature that has no choice but to be fully in a world that does not play with blood and bones, bruises and scars, life and death.

The spatial experiments of Noguchi, the call toward living-in-life of Arakawa and Gins, the radical projects of unscripted play for its own sake, all speak to a need for creating a world compassionate to a state of infinite play – in ways that “refuse to die.” Like the boundaries of playpens, the rules of tag, and the right way to go down a slide, “growing up” has always been more of a suggestion. As Hermann Hesse writes in The Journey to the East (1932), before the narrator is reproached by the League for leading a “dreadful, stupid, narrow, suicidal life” and selling his violin: “children live on one side of despair, the awakened on the other side.”25 So, amid the dark days in which “a conversation about trees is almost a crime,”26 living in play, on the other side of despair, poses the task of escaping, as Roger Gilbert-Lecomte wrote, “the closed vessel of the horizon,” which can be guided by his words: “If he opts for the impossibility all he has to do is take advantage of his solitude to sing children’s songs and act like a clown. . . . If he decides it’s possible he must discover a way out. . . . A rational being, seeking to experience a limited space, and thus uninterested, presupposes that he has never seen, at any moment of his life, the possibility of a way out – I say that is a lie!”27

Footnotes

- Audre Lorde, The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde (2000; New York: W. W. Norton & Company), 169

- The scaffold itself can become a form of play, as with the visionary (but never built) Fun Palace, a concept co-created by theater director Joan Littlewood and architect Cedric Price in 1961, which anticipates the tame interpretations of contemporary modular design. Littlewood and Price envisioned the Fun Palace as a collective space where “you choose what you want to do – or watch someone else doing it,” which “must last no longer than we need it.” Quotations from a brochure for the Fun Palace project (1964), courtesy of the Canadian Centre for Architecture.

- “Junk and Adventure: 20th Century Playground Archive,” Collecting Childhood (blog), January 7, 2015, https://collectingchildhood.wordpress.com/2015/01/07/junk-and-adventure/

- Kevin Paul (KABOOM!), “Why the Fight for Access to Playgrounds is a Racial Justice Issue,” OPENSpace: National Recreation and Park Association, February 24, 2021, https://www.nrpa.org/blog/why-the-fight-for-access-to-playgrounds-is-a-racial-justice-issue/.

- “Space to Play: West Bank refugee camps are facing a crisis of safety and square feet,” Defense for Children International: Palestine, October 5, 2017, https://www.dci-palestine.org/space_to_play.

- Jenny Brewer, “From lamps to playgrounds, Isamu Noguchi believed sculpture should be omnipresent,” It’s Nice That, December 13, 2021, https://www.itsnicethat.com/features/isamu-noguchi-art-131221.

- “In spite of a veneer of optimism and initiative, modern man is overcome by a profound feeling of powerlessness which makes him gaze toward approaching catastrophes as though he were paralyzed. Looked at superficially, people appear to function well enough in economic and social life; yet it would be dangerous to overlook the deep-seated unhappiness behind that comforting veneer. If life loses its meaning because it is not lived, man becomes desperate. People do not die quietly from physical starvation; they do not die quietly from psychic starvation either.” Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (1941; repr., New York: Avon Books, 1971), 282.

- Léopold Lambert, “Domesticity in the Reversible Destiny’s Architectural Terrains,” The Funambulist, October 29, 2012, https://thefunambulistdotnet.wordpress.com/2012/10/29/arakawagins-domesticity-in-the-reversible-destinys-architectural-terrains/.

- This echoes third space theory on the liminal possibilities and emergence of the subaltern described by Homi K. Bhabha in The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994, 52), wherein he examines instances that “simultaneously mark the possibility and impossibility of identity, presence through absence.”

- Elizabeth Grosz, Architecture from the Outside: Essays on Virtual and Real Space (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001).

- Grosz, Architecture from the Outside, 65.

- Reference to Werner Herzog’s book Conquest of the Useless (New York: Ecco, 2009), in which the director documents the physically and psychically grueling work of filming Fitzcarraldo (1982) and bringing “Grand Opera to the jungle.”

- Alexander Trocchi, Cain’s Book (New York: Grove Press, 1960), 245.

- Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory (1970; repr., New York: Continuum, 2002), 39.

- Adorno adds on the aversion toward the childish in the evolution of modern art, which he refers to as a straining toward maturity: “Art brings to light what is infantile in the ideal of being grown up. Immaturity via maturity is the prototype of play.” Aesthetic Theory, 43.

- Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning (New York: Washington Square Press, 1984), 129.

- This existential vacuum, or as Frankl describes, “the frustrated will to meaning,” opens a Pandora’s box of repressed yearnings, made emotionally or materially inaccessible in our contemporary world. In Wind, Sand and Stars, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote a passage on love that can be read for any great dreams, desires, and pursuits: “Men who have lived for years with a great love, and have lived on in noble solitude when it was taken from them, are likely now and then to be worn out by their exaltation. Such men return humbly to a humdrum life, ready to accept contentment in a more commonplace love. They find it sweet to abdicate, to resign themselves to a kind of servility and to enter into the peace of things.” Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Wind, Sand and Stars (New York: Time Life Books, 1965), 106.

- Claire Aislinn Petelczyc et al. “Play at Work: An Integrative Review and Agenda for Future Research,” Journal of Management 44, no. 1 (January 2018): 161–90, https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317731519.

- Chris Kraus, “Kathy Acker’s Blood and Guts in High School,” The Paris Review, November 9, 2017, https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/11/09/kathy-ackers-blood-guts-high-school/.

- Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning.

- In his book When the Body Says No, Gabor Maté defines proximate separation as physical closeness but emotional separation. “The levels of physiological stress experienced by the child during proximate separation approaches the levels experienced during physical separation,” he writes. “People trained in this way in childhood are likely to choose adult relationships that re-enact repeated proximate separation dynamics. They may, for example, choose partners who do not understand, accept or appreciate them for who they are.” Gabor Maté, When the Body Says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2012), 209.

- Judith Herman, Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence – From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror (New York: Basic Books, 1992).

- Pete Walker references a term adapted by many childhood trauma psychologists and psychoanalysts, including Leonard Shengold in Soul Murder: Child Abuse and Deprivation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989). Shengold, in turn, attributes the term to the nineteenth century, when it was used by the Scandinavian playwrights Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg. In the introduction to his book Soul Murder Revisited, Shengold wrote: “There is a universal psychological resistance to the idea of a bad – a depriving or abusing – parent. . . . Denial of child abuse is tempting because no one wants it to take place; it is one of those events that, to paraphrase Freud, disturbs the peace of the world.” Leonard Shengold, Soul Murder Revisited: Thoughts About Therapy, Hate, Love and Memory (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), accessed April 15, 2022, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/first/s/shengold-soul.html.

- Pete Walker, Complex PTSD: From Surviving to Thriving (Lafayette, CA: Azure Coyote), 2013.

- Hermann Hesse, The Journey to the East (London: Panther Books, 1975), 98, 100.

- From Bertolt Brecht’s poem “An die Nachgeborenen,” trans. Scott Horton, Harper’s, January 15, 2008.

- Roger Gilbert-Lecomte, The Book is a Ghost: Thoughts and Paroxysms for Going Beyond, trans. Michael Tweed (San Francisco: Solar Luxuriance, 2015), 82–83.

Lital Khaikin is a writer based in Tiohtiá:ke / Montreal. Her chapbook-length poem Outplace (2017) was published with the San Francisco-based press Solar Luxuriance, with other literary experiments appearing in and around 3:AM Magazine, Berfrois, Tripwire, and the “Vestiges” journal by Black Sun Lit. She has contributed journalism to Canadian Dimension, Toward Freedom, Warscapes, Briarpatch, and elsewhere. She is completing a novella called flight and embarking on a second novella called nigredo.