Counter-Infrastructures, part 2

Sarrita Hunn

December 2024

This essay continues from Counter-Infrastructures, part 1.

Counter-Curriculums / Counterpublics

Building on her own work as a socially engaged, community-oriented artist, writer, and educator, Fiona Whelan helped found the MA/MFA in Art and Social Action program at NCAD in 2023, building on previous postgraduate programs at the college. In a 2019 essay, “A Dublin based MA in Flux,” describing the development and evolution of the MA program, she discusses the challenges of formalizing socially engaged and collaborative practices in an academic context:

Practitioners with socially-engaged and collaborative practices are so often involved in multiple concurrent processes, which can’t be seen as a linear story. Relational processes are inherently messy, many of them take place in private, they engage complex relations of power from intimate group structures to larger political economies, with layered negotiations on the go at once. These practices require a level of comfort on the part of those engaged, in not knowing where something is going . . . At a time when the field of socially-engaged practice has been professionalized, the same principles of openness and not knowing need to apply at the meta-level of the field of practice. Many clear definitions have emerged to define and categorize approaches to practice, each with their own language and characteristics; increasingly named, framed and funded. […] In an era overwhelmed with capitalist modes of control and governance, where pedagogy in the university is increasingly managed and learning prescribed, the biggest challenge in formally educating practitioners in the professionalized field is to hold open the space of not knowing and avoid determining the future of the field of practice — in other words, colonizing the future, with the present.1

One strategy the MA program has used to counter this tendency towards ossification is through partnerships with local, national, and international collaborators; for example, as the UK and Ireland hub for the Creative Time Summit in 2016 and through TransActions — dialogues in transdisciplinary practice, an international collaboration with Stockyard Institute at DePaul University in Chicago. Building on the program’s innovation within a formal academic context, Nuraini Juliastuti shared her experience as a member of KUNCI Study Forum & Collective (co-founded in 1999 in Yogyakarta, Indonesia) in developing the School of Improper Education (SoIE) through an extended workshop with the MA/MFA students and an introductory panel at the Counter-Infrastructures symposium. The School of Improper Education is a long-term collective learning process initiated by KUNCI in 2016. The first phase of the school was inspired by the French teacher Joseph Jacotot as discussed by Jacques Rancière in The Ignorant Schoolmaster (1991) and included (1) breaking down the hierarchy of a formal education system/institution; (2) redefining the ideas of the “masters”; (3) “going below” as inspired by the Institute for the People’s Culture (Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat, or Lekra); and (4) Taman Siswa (Garden of Students), an anti-colonial school established in the 1920s during Dutch colonization in Indonesia.2 As the editors of MARCH’s most recent publication Tools for Radical Study: A Collection of Manuals (Spring 2024), KUNCI included an English translation of “Principles of Art Education in Taman Siswa,” written by Sindoedarsono Soedjojono and Sindhusiswara in 1954. As KUNCI summarizes in their introduction to the publication:

We treat KUNCI’s editorial role in Tools for Radical Study as an opportunity to network and cross-reference our educational initiative, the School of Improper Education, with other initiatives and their publics. We understand cross-referencing as a framework to provide a grounded understanding of local study contexts while also engaging in the mobility and connection of people, ideas, tools, and institutions that, in turn, multiply the frame of references in each implicated study practice. Inhabiting the space of sharing and collectivity, this multiplication creates a commons-based production of knowledge rather than a centralized accumulation of intellectual property. All contributors to this publication offer alternative forms of studying that are fundamentally practiced as a mode of sharing and nurturing alternative publics or counterpublics. Counterpublics are a radical form of commons as long as they are formed by a shared dissatisfaction with the dominant mode of schooling and advocate for the redistribution of the right and ability to think, study, and collectivize knowledge.

In his seminal thesis on “print capitalism,” Benedict Anderson argues that imagined communities are formed through the proliferation of printing technologies, which maximize the circulation of languages, discourses, and an affective sense of national belonging. Embracing print culture but at the same time resisting capitalism, our publication works toward sharing common tools and commoning a network of study communities. Publishing can be a soft infrastructure to facilitate the reproduction and redistribution of commons. Thus, for us, making a publication is not only about publishing something to show the world who we are and what we think — it is also about reaching out to people to create a community of study. It is a process as simple as forming a new friendship and as complicated as organizing a sustainable, trans-local network.3

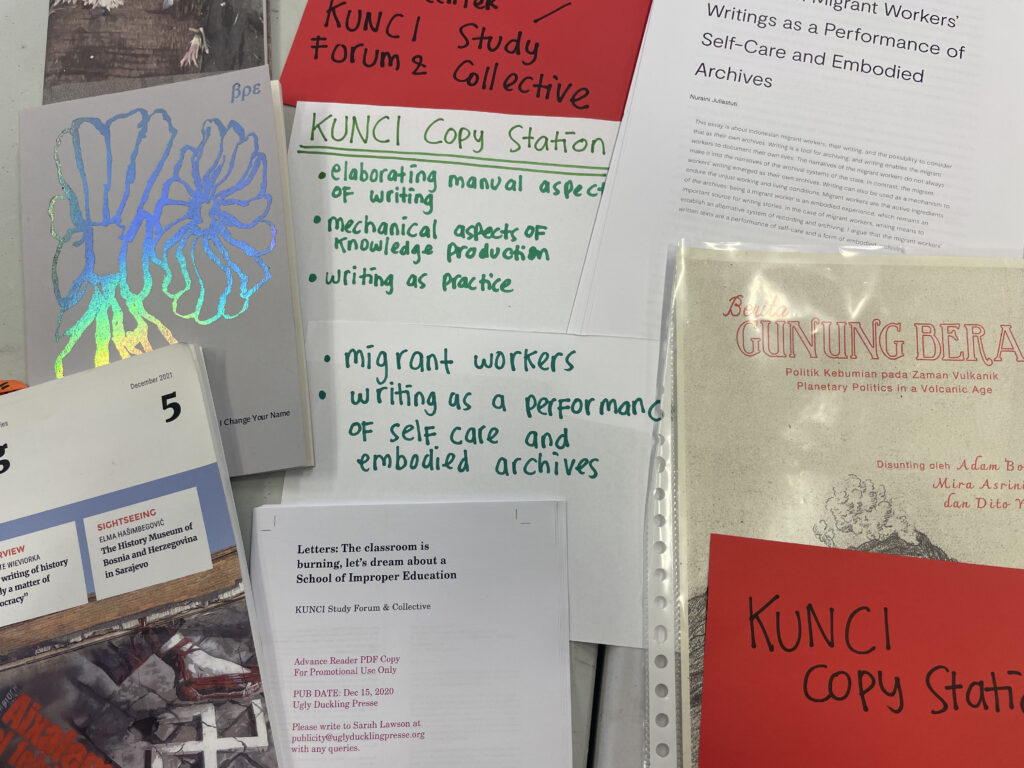

KUNCI Copy Station, a selection of publications shared during Nuraini Juliastuti’s counter-curriculums workshop at Counter-Infrastructures: Art & Activism symposium, NCAD, Dublin, Ireland, December 2023.

In the November 2022 edition of the School of Improper Education, KUNCI moved from envisioning a “garden of students” to imagining a “forest of students” (Hutan Siswa) — resting on fertile ground and nurturing the development of interconnected study clusters around pressing matters within the social environment. Acting as a kind of foliage for the forest of students, these clusters included (1) practicing refusal; (2) justice and intersectional care; (3) community education; (4) solidarity economy; and (5) sustainable economy. In this way, Juliastuti describes SoIE (following Raunig) as always fleeing; whereas formal institutions might have the advantages of art world connections that can lead to (unexpected) opportunities, allies, and collaborators, informal or “alternative” institutions can become a kind of refuge, especially in the context of colonialism.4 In “The Studying-Turn: Free Schools as Tools for Inclusion,” Juliastuti writes:

An alternative space, as expounded in my previous research, refers to new cultural spaces — an artist-run space, gallery, performance space, or discussion place — for thoughts that would otherwise be “homeless” in the cultural spaces formed and designed by established cultural authorities. These spaces are composed of a group of individuals with different backgrounds and trajectories who develop their own attitudes to test their thoughts on arts and culture.

Their works range from art production and research and are all conducted with clear interdisciplinary intention: be it for the provision of art and culture that in turn supports wider infrastructure, or to facilitate dialogue with policy makers, or to organize activities that can be classified as community empowerment. An alternative space serves as a model platform for artists and cultural activists to fulfill their visionary ideas.5

Counter-Archives / Participatory Action

If the widening gap between arts and technology must be placed within the larger political context of privatization, particularly of land, then it is perhaps no surprise that the two Counter-Infrastructures symposium guests who work with archival practices are both concerned with urban space and gentrification. Operating between architecture, urban planning, and art, Sara Brolund de Carvalho is a lecturer at KTH School of Architecture in Stockholm, Sweden, and a founding member (with Helena Mattsson and Meike Schalk) of Aktion Arkiv. She has written about citizen participation in urban planning, feminist architecture, collective housing, and common spaces that touch on concepts such as spatial care and community building. She is the co-editor (with Meike Schalk and Beatrice Stüde) of the publication Caring for Communities (2019), which expanded Aktion Arkiv’s interests in exploring the history and role of common rooms in Swedish welfare housing6 to ethnographic field studies around newly built common rooms in the Nordbahnviertel (Northern Railway District) in Vienna. Composed of excerpts from guided home tours and interviews, this publication served as a point of departure for a Forum Theatre piece presented in connection with the exhibition Critical Care: Architecture and Urbanism for a Broken Planet (2019) organized by the Architekturzentrum Wien (Az W) for the Vienna Biennale. In the introduction to Caring for Communities, the editors explain the importance of common rooms in community infrastructure:

We argue that common rooms are crucial to the resilience of communities and societies. To maintain important municipal infrastructures, the political importance of the common room system must be understood. The fact that Sweden has lost its original non-profit rental housing system illustrates the fragility of the non-commercial sector of welfare structures and that common goods need constant attention and care. This calls for experimentation with new forms of commons, and for communities willing to create and maintain these welfare structures.

In addition to new imaginations of the commons, we require everyday infrastructures for care, such as booking systems and caretakers for common areas. Among the questions facing the future of welfare in a rapidly changing society are how to make common rooms available to the wider public in a neighbourhood, who is prepared to look after these rooms in the future, and what framework conditions are required for this. In our conversations with them, residents often pointed out that introductions to the use of common rooms are needed, that group moderation is always necessary, not just at the beginning of a housing project, and that self-organization has to be learned.7

For the Counter-Infrastructures symposium, Aktion Arkiv’s public workshop worked with local participants, including members of the Liberties Women’s History group, to examine various ways of archiving social movements. Each participant was asked to bring their own object/document as a basis to discuss personal histories within a larger context of collective histories. In a similar vein, Ed Webb-Ingall is a filmmaker and researcher working with archival materials and methodologies drawn from community video. He collaborates with groups to explore under-represented historical moments and their relationship to contemporary life, developing modes of self-representation specific to the subject or the experience of the participants. For the Counter-Infrastructures symposium, Webb-Ingall primarily discussed his work with London Community Video Archive at Goldsmiths College, University of London, and his recent film project, A Bedroom for Everyone, which was commissioned and first presented by Grand Union in September 2023. Building on Webb-Ingall’s long-term research and activist work, and time spent with housing and migrant support groups in Glasgow, Nottingham, Liverpool, Birmingham, and London, this collaboratively written animation (illustrated by lead artist Sofia Niazi and animated by Astrid Goldsmith) considers the role of grassroots activism and filmmaking in response to the current housing crisis in the UK, “while making space for the camaraderie that unfolds in the community centres and meeting halls where this work takes place.”8 For Ed Webb-Ingall (like Nuraini Juliastuti and many presenters of the symposium), the line between cultural work, archival work, and activism is a blurry one.

Counter-Institutions / Social Imaginaries

When moving from the margins to the mainstream, Eve Olney believes the potential for transgression can get lost. Dr. Olney is a socially engaged artist, activist, curator, educator, and practice-based researcher. Incorporating a feminist ethnographic approach to social change, Olney’s praxis uses creative methodologies to construct alternative social imaginaries. Her work is greatly influenced by the writing of Greek-French philosopher and political theorist Cornelius Castoriadis, who explored a conception of the social imaginary in books such as The Imaginary Institution of Society (1987). Like Silvia Federici, Castoriadis finds approaches that lean too heavily on a Marxist idea of autonomy and social institutions lacking in feminist (self-)criticality.9 Experiencing this lack in the field of architecture (alongside academic burnout) and, later, in the power dynamics that play out in grassroots and even anarchist collectives, Olney returned to Cork, Ireland and founded The Living Commons, “a not-for-profit socially-engaged arts organisation that was established in order to found and maintain co-operative, humane, democratic living, working and learning schemes for persons in precarious living situations through creative practices and community building.”10 As both a response to and critique of socially engaged practices in Ireland, the creation of a dedicated, ongoing space allowed for longer-term commitments and developments to take hold that sporadically funded projects do not make possible.

Alongside other ongoing efforts (including r.a.g.e., a feminist creative collective that challenges patriarchal social structures, inequalities, and injustices; and Cork Democratic School, a self-directed learning school), Olney later co-founded the Radical Institute with Dr. Krini Kafiris as a “transnational initiative that explores how the arts and cultural practice can promote and sustain radical social and ecological change to transform our social/political movements and create new worlds,”11 which additionally acts as a self-reflective tool for The Living Commons. Drawing from the works of Black feminists such as Audre Lorde and bell hooks, eco-feminists such as Joanna Macy, and training models such as the Ulex Project in Barcelona, the Radical Institute looks to develop “radical cultures of care” that integrate a social ecological concept, particularly as defined by activist Murray Bookchin, of how we think of ourselves. In a 2020 article, “Commoning-Based Collective Design: Moving Social Art Practice Beyond Representational ‘Rehearsals’ Into Concrete Social Solutions,” for the art research journal Passepartout’s issue on New Infrastructures, Olney explains:

The underlining organizational principles are drawn from political theorist Cornelius Castoriadis’s argument for an ethical and political project of social organisation, which is based upon self-governance through an ongoing process of common assemblies, and Murray Bookchin’s conception of communalism, where “every productive enterprise falls under the purview of the local assembly . . . to meet the interests of the community as a whole.”12

Here, the autonomy of the individual is directly related to the autonomy of the collective, and that is all interconnected to the ecologies of nature — so you can’t think of these as isolated components. For Bookchin, this also meant breaking from the anarchist movement’s emphasis on class. As Janet Biehl, Bookchin’s long time collaborator, writes in “Bookchin Breaks with Anarchism” (2007):

Perhaps the limits of capitalism, he thought, were environmental or ecological in nature. But those problems affected everyone, regardless of class. The revolutionary agent, in an ecological rebellion against capitalism, would then be not the working class but the community as a whole. Opposition to capitalism could become a general, transclass interest. This assumption — that citizens, not workers, were the revolutionary agent of greatest significance — remained foundational for the rest of his life.13

Now, we might wonder: What would a form of communalism, where “every productive enterprise falls under the purview of the local assembly . . . to meet the interests of the community as a whole” look like? The final presenters of the Counter-Infrastructures symposium, Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (LABOFII), provide some examples, such as with their film Paths through Utopias, shown above.14 I first learned about LABOFII at the Artist Organizations International (AOI) “congress” initiated by artist Jonas Staal and curators Florian Malzacher and Joanna Warsza at Hebbel am Ufer (HAU) in Berlin, Germany, which I wrote about for Temporary Art Review in 2015. While I generally felt that the event problematically conflated one conversation around the fact that forming an artist organization is inherently a political act in itself, and a second conversation that seeks to define the relationship between art and politics (or more specifically activism), I was especially impressed with closing comments by LABOFII co-founder Jay (formerly John) Jordan, who summarized it best — the biggest question we have to reconcile is the relationship between local and global efforts. She stated (see 1:49:55):

As someone who’s spent a lot of time in big rooms with a lot of diverse people, trying to find common ground, and having discussions — Are we an organization? Are we a network? I mean, I have probably spent 20 years of my life with groups of people trying to decide that — one of the things that I think touches me the most now is actually the conflict between the local and the global . . . especially when it comes to issues of climate and transport and movement . . . and how we articulate the two. I think maybe the 21st century is going to be about this question more than any other question — What is our territory? — especially within the world of contemporary art, where we are pretty much de-territorialized, uprooted. John Berger said a beautiful thing, he wrote: to transform a thing, you need to know its texture — and to know its texture, we need to really be embedded in our territories. For me personally, it’s a huge conflict. I’m trying to be embedded in a territory in rural France and work with rural farmers and so on, but I’m constantly taken to events like this because economically it’s how I make my living, but it is also way more glamorous than sitting in a fucking field. For me, this is the biggest question . . . How do we create this whilst knowing the texture of the thing we want to transform? [Because] in the end, that’s where we can make the change happen, at home.15

Later, I crossed paths with LABOFII again when I attended the first edition of Training for the Future, an initiative also developed by Studio Jonas Staal, curated by Florian Malzacher in conjunction with the 2019 Ruhr Triennale, and written about for MARCH by Sumugan Sivanesan. Organized by co-founders Jay Jordan and Isa Fremeaux, this LABOFII workshop was further expanded on in a book with the same title, We Are “Nature” Defending Itself, released by Pluto Press in 2021. The book, like the final discussions at the workshop, “chronicles the story of the ZAD (zone to defend), a resistant land occupation emerging out of a decades-long struggle which stopped a new airport project”16 in rural France, as well as the authors’s own “fleeing” from their housing and cultural work in the UK to living at (and defending) the ZAD full-time. While the book, along with the recent award winning documentary DIRECT ACTION (2024), provides great insight into the history of this notable self-managed autonomous zone, for this essay, I would like to highlight their writing on the role of art or, more precisely, “Art-as-we-know-it,” quoted at length here:

According to art historian Larry Shiner, Art-as-we-know-it is “a European invention barely two hundred years old” — a bit older than classical biology but premised on an equally dangerous logic. Like notions of biology that beguiled us into believing that life is a competitive battlefield for survival, the idea of Art-as-we-know-it has been a weapon of capitalism and colonialism. Art with a capital A, the singular works of an almost always white, male genius, is presented as the definition of “advanced civilization,” differentiating us from barbarians.

For most of human history, and in most of human cultures, there was no single word for art distinct from life. But something unprecedented happened around 1750, right at the very onset of the industrial revolution, a revolution in the perception of art also took place. Thanks to fossil fuels, industrialism was the first time the processes of making things became independent of human and animal power, disconnected from seasons, weather, wind, water, and sun. Making became independent of place, as coal and then oil amplified the logic of extractivism and the planetary plundering accelerated.

But among the rising middle classes of the metropolis, the violent rift was being formed between art and craft, genius and skill, tradition and invention, the beautiful and the useful, art and life. These separations continue to be the very foundation of the system of Art-as-we-know-it. What was once the process of inventive collaboration, such as the guilds of artisans working on a cathedral, became the possession of individual genius. Works that once had specific purpose and place (including Shakespeare’s plays!) were separated from their functional contexts. Altar pieces were ripped from their churches and put in the museums to become “paintings,” music airlifted out of rituals or carnivals and enclosed in the concert halls. Before the 1750s, the myth of “autonomous art,” a work existing primarily for itself, did not exist, neither did museums or concert halls. Before Art-as-we-know-it was invented, humans found a multitude of ways to express and celebrate what it felt to be alive. None asked to be called an artist. But like the land, art had to be enclosed to give value to the rising middle classes. Rough popular forms of culture were evicted and replaced with polite “fine” arts, for reverential contemplation and collection by the rich. Promoted worldwide by missionaries, armies, entrepreneurs, dealers, and intellectuals, this new invention was another engine of “progress” and a sign that the hierarchies being imposed were natural. A civilization that could produce what were presented as “great works of art” was destined and entitled to rule. The idea and ideals of Art-as-we-know-it continue to colonize imaginations everywhere.17

Counter-Infrastructures

If the idea of Art-as-we-know-it has only existed in the last couple of centuries, the professionalization of the field in general, and of social practices specifically (for example, as discussed by Fiona Whelan earlier), is an even more recent phenomenon. In her 2018 essay “What’s Love Got to Do with It… Remembering Ted Purves,” CCA alum Lynne McCabe discusses her own struggles with not only the way that “funding and further success of many socially-engaged art projects were dependent upon gaining recognition from the very capitalist art world systems they purportedly resisted,” but the ways that “projects that deployed socially-engaged artists and their practices as agents of urban regeneration” most often simply become “a distraction to the people who lived there from the harsh fact that they were still being under-served, lacking basic infrastructure needs like working street lights, grocery stores, safe spaces for children to play, and reliable bus services.”18 For these reasons, like McCabe, I often felt great skepticism about any actually transgressive role that a socially engaged artist might play, as well as Purves’s emphasis on the “gift economy” as a potential solution. While “Ted saw the giving of a gift and its subsequent ties of obligation as a strategy for creating ‘kinship’,” having grown up in a rural working-class environment like McCabe, I also felt that “a gift given from outside one’s community or class comes with an ‘obligation’ that instead of binding together serves to delineate the ‘haves’ from the ‘have-nots.”19 But also like McCabe, my understanding of what Ted meant by “generosity” has dramatically changed with time. She states:

At the end of one of our particularly frustrating discussions, a weary Ted turned to me and said: “Sure, it’s easy to point out what’s wrong with these practices. It’s easy to make critical work that merely points a finger at their failings and sort of simultaneously pats yourself on the back for being smart in figuring it out. But what are you offering in these broken models’ stead? What really are you giving us? What are you willing to risk? And where is your generosity?”

This challenge to turn away from cynicism towards a more generative, generous practice produced a feeling of unease in me and spurred me to action. I realized I was feeling paralyzed and exhausted making work that only reflected what was lacking in the various methodologies and practitioners of socially-engaged art. How could this circulatory negation ever add anything positive to the discourse?20

In other words, whether because of real class struggles or nation-states leveraging their power within current funding infrastructures, it is even more clear today that “Ted’s optimism was in itself an act of resistance to the pernicious sense of scarcity that pervades not only the art world but — as we see in current political discourse — seemingly every community, regardless of privilege or resources.” Or, as Jay Jordan and Isa Fremeaux frame it:

Two centuries on, many are still caught in the trap of Art-as-we-know-it, representing the world rather than transforming it. Showing us the crises rather than genuinely attempting to stop them or create solutions. It’s as if someone had set your home on fire and instead of trying to extinguish the blaze, you took photos of the flames. What kind of separation must have to take place in our minds that when faced with such an existential emergency we think only of representing it? And whom do such “pieces” serve, ultimately?21

[…] Why make an installation about refugees being stuck at the border when you could co-design tools to cut through fences? Why shoot a film about the dictatorship of finance when you could be inventing new ways of moneyless exchange? Why write a play inspired by neo-animism when you could be co-devising the dramaturgy of community rituals? Why make a performance reflecting on the silence after the songbirds go extinct when you could be co-creating ingenious ways of sabotaging the pesticide factories that annihilate them? Why make a dance piece about food riots when your skills could craft crowd choreographies to disrupt fascist rallies?

Why continue with Art-as-we-know-it, when you could desert this Nero culture, which fiddles while watching our world burn?22

Of course, what makes this challenging is that it requires “fleeing” — at least from Art-as-we-know-it — and comes with no small amount of uncertainty; or, to be more precise, it lays bare the illusion of certainty masked by convenience. Two decades after What We Want is Free was first published, it additionally occurs to me that perhaps too much emphasis was placed on the “free” part of that statement and not enough on the “we”; it is one thing to talk about generosity from an individual perspective, but quite another to talk about it as a collective act. While socially engaged practices may generally reject the idea that culture must be defined and produced by perceived scarcity, counter-infrastructures ultimately require an ongoing and distributed commitment only possible through collaborative and collective action. For me, this has meant a continued exploration of the relationship between art and technology alongside a post-pandemic shift toward the local. While our previous work with Temporary Art Review was defined by “the ways in which institutional thinking incubating in Europe and embodied practices in the United States could be brought into productive tension”23 (later exemplified by MARCH’s first print publication, which “occupied” the first issue of October journal), more recently I have been struck by a similar tension between the Art-as-we-know-it world’s proliferation of discussions around institutional critique (as we are discussing here) and the hacktivist practices that are actually building digital counter-infrastructures. In other words, there are a multitude of artists and curators who critique capitalism while using corporate platforms like Instagram and Google Docs, but there are an equal number of innovative programmers who make great tools with little effort made to share them with a wider public. As Gerald Raunig writes succinctly in his most recent book Making Multiplicity (2024):

Alternative projects cannot be limited to preventive appropriation controls, but must develop new forms of caring use, propertyless occupation, and poor possession. In the techecological realm, one such new form emerged a few years ago as the fediverse — an assemblage of independent and decentralized social networks, microblogging sites and publishing platforms, the best-known of which is Mastadon. The so-called fediverse “instances,” often of very different size, are set up on their own servers and are independent of each other, but they can also interact and link up with other instances at any time. This form of federation and interoperability in the fediverse, along with its consistent use of free software and involvement of users in self-organization, is a huge step forward compared to corporate social media with their massive restrictions and commercial interests.24

Raunig then goes on to explain that “an important issue arising out of the still relatively short history of net culture” is the need to consider not only forms of “coupling and bracing” but also “decoupling, blocking and defederation.” In other words, the development of the fediverse uses a kind of counter-power strategy. It is an attempt at building networked counter-infrastructures while disinvesting in platform capitalism and state-controlled and regulated technologies such as proprietary software and copyrights; in other words, to make it free – and under local control. However, the potential does not stop there: “This variability and multiplicity is also a prerequisite for the possible further development of the fediverse beyond federation.” Historically, “federation refers to the structure of a political body,” and so this process of borrowing can easily be reversed by “joining the infrastructural conditions of the fediverse with dividual usage.”25

Following my work related to online visibility (and MARCH’s Publishing As Protocol feature mentioned earlier), in 2023 I became a co-founding member of offline, a former cafe turned collectively run community space in Berlin. True to its name, offline has no internet connection (or mobile phone reception), emphasizes in-person participation, and has developed an innovative organizational structure inspired by anarchist methodologies (e.g., consensus decision-making by assembly) and trust networks borrowed from online computing. Offline hosts a mix of collective meetings, public events, and ongoing working groups, reminiscent of the “common rooms” researched by Aktion Arkiv (also called freiräume or “open rooms” in German), and uses the formalized structure of a Verein (association) to hold accounts and contracts in common while organizing the activities of the space in a more horizontal manner. In essence, the prerequisite for getting involved is simply to show up, and, in this way, the emphasis is not just on ideas borrowed from federated networks, but local-first “post-internet communication infrastructure” (such as Secure Scuttlebutt or p2panda), which communicate machine-to-machine with no traditional servers required. Among other goals, offline aims to facilitate the radical redistribution of time, energy, resources, and knowledge while recognizing that different people have different capacities, resources, and skill sets to offer. As a predominantly migrant community (with an explicit emphasis on prioritizing the collective work of marginalized groups such as those connected to the so-called Global South), this work has become increasingly important in the (local) context of ongoing tech-boom gentrification and pending austerity measures within state funding.

As “fleeing” becomes increasingly less of a choice for more and more people, the curricula, archives, institutions, and technologies I have mentioned here are just a few types of “counter-infrastructures” to consider. For example, The Hologram comes to mind as a feminist peer-to-peer protocol and collective care network (also written about by Cassie Thornton); as well as the Counterpublic triennial (founded by James McAnally) situated in St. Louis, MO, which aims “to reimagine civic infrastructures towards generational change”26 (perhaps most notably exemplified in their role facilitating the recent transfer of the last intact Mississippian mound to the Osage Nation); and the Center for Liberatory Practice & Poetry, “an experiment in access-centered political education for collective autonomy and governance beyond the state”27 (seen, for example, in their Values & Practices). With so many potential counter-infrastructures blossoming, we can continue to fight for the perceived scarcity of Art-as-we-know-it “while watching our world burn,”28 or we can divert our surplus (time, energy, and resources) in service of collective ways of organizing that are both highly localized and internationally networked. This is one way, at least, I can imagine we might develop durable and meaningful counter-infrastructures beyond our immediate crises: “Maybe not for art initiatives to gain political domination (yet), but at least to achieve some form of sustainable infrastructural networks.”29

Rukmini Kelkar. Notes taken during the Counter-Infrastructures: Art & Activism symposium, NCAD, Dublin, Ireland, December 2023.

Footnotes

- Fiona Whelan, “A Dublin based MA in Flux,” in Uncertain Patterns: Teaching and Learning Socially Engaged Art, ed. Microsillons (HEAD, 2019). See also Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, “The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study,” in Boundary 2: an international journal of literature and culture (Minor Compositions, 2013). [link]

- See, for example, Brigitta Isabella, “Belajar bersama: dengan sekaligus tanpa The Ignorant Schoolmaster (Learning Together: With and Without The Ignorant Schoolmaster),” Sekolah Kunci, July 24, 2017. [link]

- KUNCI Study Forum & Collective, “Tool for Radical Study,” MARCH: a journal of art & strategy, March 2024. [link] On counterpublics and the queerness of print culture, see Michael Warner, Publics and Counterpublics (Zone Books, 2002). See also Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflection on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Verso, 1991).

- See, for example, Ting-kuan Wu, “Being An Activist Artist: Interview with Nuraini Juliastuti,” Nusantara Archive, June 26, 2019, link; and Nuraini Juliastuti and Ade Darmawan, “Ruangrupa: A Conversation on Horizontal Organisation Being,” Afterall 30, June 7, 2012, link.

- Nuraini Juliastuti, “The studying-turn: Free schools as tools for inclusion” in The Force of Art, ed. Nora Khan, Carin Kuoni, Gabi Ngcobo, and Jordi Barta Portoles (Valiz, 2020), 263–282, available at link.

- See, for example, Sara Brolund de Carvalho and Meike Schalk, “Rituals of Care: Reimagining Welfare,” NORDES 8, 2019. [link]

- Meike Schalk, Sara Brolund de Carvalho/Aktion Arkiv, and Beatrice Stude, eds., Caring for Communities (Aktion Arkiv Publishing, 2019), 30.

- “Ed Webb-Ingall: A Bedroom for Everyone,” Grand Union, accessed December 27, 2024. [link]

- See Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation (Autonomedia, 2004).

- The Living Commons, accessed December 26, 2024, https://www.thelivingcommons.com/.

- “Radical Institute,” The Living Commons, accessed December 26, 2024, link.

- Eve Olney, “Commoning-Based Collective Design: Moving Social Art Practice Beyond Representational ‘Rehearsals’ Into Concrete Social Solutions,” Passepartout 40 (2020): 209. Quoting Murray Bookchin, The Next Revolution: Popular Assemblies and the Promise of Direct Democracy (Verso, 2015), 17–18.

- Janet Biehl, “Bookchin Breaks with Anarchism,” Communalism: International Journal for a Rational Society 12 (October 2007): 1. Also available at: link.

- See also the publications Beautiful Trouble and Notes from Nowhere, We Are Everywhere: The Irresistible Rise of Global Anti-Capitalism (Verso, 2003).

- “Artist Organisations International. 6. Final Debate,” February 2, 2015, posted by Jonas Staal, Vimeo, 2:45:41, https://vimeo.com/118486463.

- Description by Pluto Press, accessed December 26, 2024, link.

- Jay Jordan and Isa Fremeaux, We Are “Nature” Defending Itself: Entangling Art, Activism and Autonomous Zones (Pluto Press, 2021), 126–127. See also Larry Shiner, The Invention of Art: A Cultural History (University of Chicago Press, 2001), 3.

- Lynne McCabe, “What’s Love Got to Do with It . . . Remembering Ted Purves,” SFMOMA Open Space, July 4, 2018, link.

- McCabe, “What’s Love Got to Do with It.”

- McCabe, “What’s Love Got to Do with It.”

- Fremeaux and Jordan, We Are “Nature” Defending Itself, 126.

- Fremeaux and Jordan, 20.

- Hunn and McAnally, From New Institutionalism to New Constitutions.

- Gerald Raunig, Making Multiplicity (Polity, 2024), 81–82.

- Raunig, 82–85.

- See, for example, our joint publication of their 2023 catalog.

- Center for Liberatory Practice & Poetry, accessed December 26, 2024, https://liberatorypractice.org/.

- Fremeaux and Jordan, We Are “Nature” Defending Itself, 20.

- Joshua Simon, “The Dual Power of Arts Organizations.”

Sarrita Hunn is an interdisciplinary artist, editor, curator, and web developer whose often collaborative practice focuses on the culturally, socially, and politically transformative potential of artist-centered activity. She is a Founder and Editor of MARCH: a journal of art & strategy; Assistant Director of Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art; and in 2021 a Curator for Activist Neuroaesthetics, a festival of events celebrating the 25-year anniversary of artbrain.org.